IF YOU regularly travel to the New South Wales bush, you’ll be happy to know there’s a group of coppers ready to respond to a ‘help me’ when needed.

They’re the lads and ladies of NSW Police Rescue, and in 2017 they’re celebrating 75 years of operation.

The unit traces its existence back to the early 1940s, when the task of establishing what was then known as the NSW Police Cliff Rescue Squad was entrusted to an ex-Sydney Harbour Bridge rigger, Harry Ware.

Harry wasn’t a sworn-in constable with the NSW Police, but he was the ideal choice as he had prior involvement with the National Emergency Service of NSW (a distant forerunner to today’s State Emergency Service) and he trained the early rescue crew and was the first boss.

Harry wasn’t a sworn-in constable with the NSW Police, but he was the ideal choice as he had prior involvement with the National Emergency Service of NSW (a distant forerunner to today’s State Emergency Service) and he trained the early rescue crew and was the first boss.

In reflection of his expertise, and with reference to his role in the squad, he was later appointed to the position of special constable with the rank of sergeant into the NSW Police.

By 1953, with the unit’s increasing role in attending car crashes (car ownership was increasing and, with negligible safety technology, proportionately more people were killed and injured) and other non-cliff-related tasks, the unit’s name had been consolidated to NSW Police Rescue Squad.

By 1953, with the unit’s increasing role in attending car crashes (car ownership was increasing and, with negligible safety technology, proportionately more people were killed and injured) and other non-cliff-related tasks, the unit’s name had been consolidated to NSW Police Rescue Squad.

Over the decades the Rescue Squad has gone from strength to strength, and it has attended some of the worst accidents, incidents and disasters nation-wide (see Crush Syndrome). These days, the Rescue Squad in Sydney also includes the Bomb Disposal Unit and supports other police units in various incidents, from search-and-rescue operations to sieges.

OUTDOOR OFFICE

NSW Police shares the responsibility of Rescue with other entities within the state such as Fire Rescue NSW, Ambulance Service NSW, State Emergency Service, Rural Fire Service and Volunteer Rescue Association.

“There’s not really any such thing as a typical week,” said the department’s Leading Senior Constable, Marcus Backway, who has been with the NSW Police Rescue Squad for a total of 13 years.

“Can you believe I was inspired by seeing Gary Sweet and Sonia Todd running across TV screens on Police Rescue?”

Backway is based, along with more than 40 other officers, in inner-suburban Sydney. The Sydney unit is the central support for the other units (and another 120 or so Rescue officers) spread all over NSW including at Lismore, Springwood, Katoomba, Goulburn, Illawarra, Newcastle and Bathurst, as well as a western region unit.

Backway is based, along with more than 40 other officers, in inner-suburban Sydney. The Sydney unit is the central support for the other units (and another 120 or so Rescue officers) spread all over NSW including at Lismore, Springwood, Katoomba, Goulburn, Illawarra, Newcastle and Bathurst, as well as a western region unit.

The breadth of what NSW Police Rescue does is enough to make your head spin. It cuts bathroom plugholes out to free kids’ fingers, extricates car-crash victims from vehicles, and it performs height, depth, confined space and industrial rescues.

However, despite the range of work the Rescue Squad performs due to NSW’s topography, steep terrain and cliff rescue – what the Squad calls ‘vertical work’ – remains an important part of their methodology, even if the word cliff hasn’t been part of the squad’s signwriting since the 1950s.

However, despite the range of work the Rescue Squad performs due to NSW’s topography, steep terrain and cliff rescue – what the Squad calls ‘vertical work’ – remains an important part of their methodology, even if the word cliff hasn’t been part of the squad’s signwriting since the 1950s.

Of course, it’s not just cliffs that require vertical access. Buildings, building sites, cranes and even the interior of bridge pylons may require abseiling (or other height-access work) for rescue or recovery.

THE VEHICLES

THE use of 4WDs is essential for rescue work, even in urban situations where something as innocuous as a steep driveway can make access difficult. The vehicles are organised and provided by what Marcus calls ‘fleet’, with input from the Police Rescue personnel who will be using them.

The vehicles are retained for 80,000km. There is a mix of Toyota Hilux and Ford Ranger dual-cabs on fleet, plus a scattering of Toyota Land Cruiser single-cabs, larger Isuzu 2WD and 4WD trucks, and a Yamaha Rhino side-by-side.

Rescue can also call for the assistance of the ultimate go-anywhere rig, the NSW Police helicopter.

Some people may be surprised, but the vehicles carry fewer accessories or modifications than your typical bush tourer. Suspension for the dual-cabs is usually standard, but requirements for carrying heavy equipment mean the Cruisers often receive a GVM upgrade.

Some people may be surprised, but the vehicles carry fewer accessories or modifications than your typical bush tourer. Suspension for the dual-cabs is usually standard, but requirements for carrying heavy equipment mean the Cruisers often receive a GVM upgrade.

Each vehicle is fitted with lights, sirens, in-cabin communication equipment, a frontal protection bar and a winch. The dual-cabs retain their factory tubs fitted with canopies which, with roof racks, are ideal for the task.

The Cruiser’s alloy work-bodies are custom-built and see service on two vehicles (160,000km) before being replaced. That’s good for the budget and minimises the time required for fit-out (performed by the Rescue personnel who use the vehicles) when new vehicles are required.

It also allows Rescue to incorporate any new ideas, technologies and equipment into vehicle fit-outs on a regular basis.

The use-twice strategy means you’re likely to see every second ex-cop Cruiser at auction with a bare back – the service bodies are stripped of the specialist equipment and left on the vehicles at the end of their second 80,000km rotation.

The use-twice strategy means you’re likely to see every second ex-cop Cruiser at auction with a bare back – the service bodies are stripped of the specialist equipment and left on the vehicles at the end of their second 80,000km rotation.

Equipment needs vary depending on the vehicle’s location and intended use. For instance, the NSW Police Rescue and Bomb Disposal vehicles we’re showing here are set up for off-road accidents and vertical rescue – two common scenarios for the Sydney-based crew.

“I’ve seen plenty of bad stuff happen in the bush,” Backway said, as the conversation during our photoshoot bounced around from suburban car crashes, to sieges and stolen guns, to the use of drones for inspecting sites and locating victims, to the topic of remote-area and off-road rescue jobs – nothing is left out.

“During floods, we do dozens of rescues of vehicle owners who have driven into floodwaters. Yes, this includes 4WDs. People think, ‘I have a 4WD, I can do this’ and they soon discover they can’t. It’s not like the ads on TV.”

There’s worse, too. In cop-speak, ‘recovery’ has a more onerous definition than the one most 4WDers understand.

“Tragically, the 4WD off-road accidents I have responded to during my career have been for the recovery of a deceased driver or passenger who wasn’t wearing a seat belt.

“Tragically, the 4WD off-road accidents I have responded to during my career have been for the recovery of a deceased driver or passenger who wasn’t wearing a seat belt.

“People think safety doesn’t matter in the bush, but there’s just as much chance – maybe even more – of getting injured and killed out there than on the bitumen.”

“People think they don’t need a seatbelt on because they’re only going slow, but all of a sudden a wheel digs in, the vehicle rolls and they fall out a window and the vehicle rolls onto them, or they’re thrown out. Plus, in the bush, it’s not as easy to get to the patient ... people may survive the crash then die later due to injuries while emergency services are on the way.”

“Riding in the back of utes is another situation. Even at walking speed people fall off and hit their head. That happens a lot.”

CRUSH SYNDROME

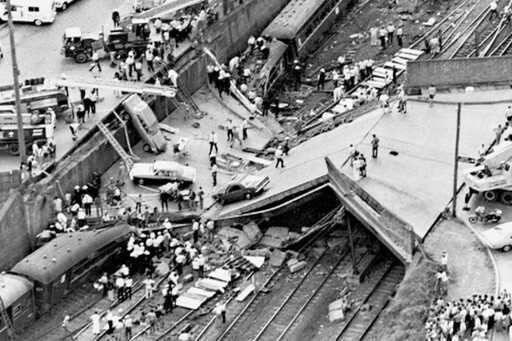

ONE of Australia’s worst transport accidents occurred in January 1977, when a train derailed and its locomotive struck the pylons of a road bridge at Granville in Western Sydney. People were killed and injured in the first carriage when a severed power pole sliced through it.

Seconds later, the concrete and steel bridge collapsed on two other carriages of the packed peak-hour commuter train. More than 80 people died. A significant factor in the death toll was crush syndrome, where trapped victims died from bloodstream toxins after being released from the wreckage.

After Granville, emergency services, including Ambulance and Police Rescue, changed strategies to better deal with crush syndrome.

After Granville, emergency services, including Ambulance and Police Rescue, changed strategies to better deal with crush syndrome.

NSW Police Rescue, along with other rescue services, also assisted with Cyclone Tracy, which all but destroyed Darwin early on Christmas Day in 1974, the 1997 Thredbo disaster, where two ski lodges toppled over as a result of a landslide, killing 18, and the 1989 Newcastle earthquake, which killed 13 people.

STILL CRUISING

TAGGING along on the Police Rescue photoshoot was Terry Psarakis and his HJ47 Land Cruiser Rescue tribute truck. Prior to leaving the cops in 1981, Terry was involved in Rescue and Highway Patrol.

He bought this Land Cruiser six years ago.

“The idea struck me to make it look representative of an old police vehicle,” he said proudly of his tireless 3.6-litre diesel-powered legend. “It’s actually not an old service vehicle, but finding and verifying one of those would be impossible. This is a tidy one that spent most of its time in Gunnedah [northern NSW]. I bought it in Sydney.”

Terry then restored the Cruiser’s paint and mechanicals, replicating the hardware such as lights and sirens of a working police vehicle.

Terry then restored the Cruiser’s paint and mechanicals, replicating the hardware such as lights and sirens of a working police vehicle.

“The canopy was built based on pictures and what I remember of these when we used them,” he said. “Some of the police-type hardware was donated, and sourcing other parts was a challenge. For instance, engine bearings are difficult. But we got there!”

As well as being an occasional cruiser, it’s used for functions like senior police personnel retirement ceremonies and memorial services.

COMMENTS