This article was originally published in the February 2012 issue of Street Machine

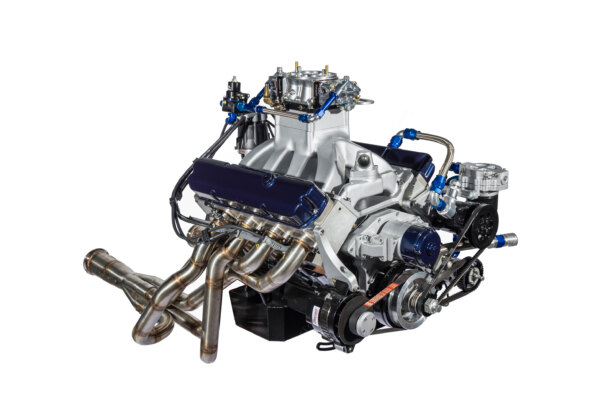

While cylinder heads, inlet manifolds, carbies and camshafts get all the glory, none of them are worth a damn without a solid foundation — the cylinder block. Here John Sidney Racing runs us through a number of specialised preparation techniques to ensure it all hangs together.

Not the sort of block modification you want. Some of the measures covered in this feature can help prevent a catastrophic failure like this from occurring

CORE SHIFT

The position of the bores is set at the factory and Mick from JSR suggests that it’s usually pretty good. However, while factory machining is generally reliable, this certainly isn’t the case with foundry work. The cores forming the water jacket around the cylinder bores can move out of position during casting (known as core shift) resulting in uneven wall thicknesses. A very thin bore wall is likely to split in a high-performance application, so checking wall thickness with a sonic tester is advisable before proceeding with any other work.

Honing is essential for every rebuild. Torque-plate simulates the forces from fitting the head and ensures a perfectly round finish. Different stones are used as the hone progresses

HONING

Boring leaves a rough finish, which is smoothed by honing. The honing tool simultaneously rotates while it sweeps up and down the cylinder, creating a bi-directional overlapping spiral hone mark that acts to trap oil.

The cross-angle of the hone mark also causes the piston rings to rotate in their grooves. Performance engines feature shallower, flatter cross-angles that create less ring rotation than the steeper angles found in street engines. But race engines rev faster, so there’s still plenty of rotation. Shallower angles don’t control oil as effectively — Mick says NASCAR and other high-end race engines use up to a litre of oil each meeting.

SLEEVING CYLINDERS

There’s been much debate about sleeving cylinders. JSR says it’s fine — if done correctly. Rather than opening the cylinder to the sleeve’s diameter through its entire length, a step should be left at the bottom for the sleeve to sit on. When the head is torqued down, the sleeve is pressed against the step, clamping it in place very firmly.

This LS block has about the most severe sleeving job we’ve ever seen! New sleeves were supported with grout – note how they key together in the middle

Ductile cast iron sleeves are best and cost around $200* each; plain reconditioning sleeves are about $50* (*prices as at 2012).

Ductile iron versions are far stronger but doing a whole V8 engine with these liners is rarely sensible because of the cost; you’re better off putting the money into an aftermarket block.

This is a line-honing machine. In normal operation the stones are flooded with coolant but it’s easier to see like this. The stones move back and forth as they rotate

GROUTING

It’s amazing how much a block can be pulled around in a performance application. With factory blocks, not only can the bores split but the entire block can split down the centre.

Grouting is one method of strengthening the lower regions of a block. A special compound is poured into the coolant jacket up to the level of the welch plugs. When it sets solid, it creates a rigid mass that prevents everything from moving about. Although effective at strengthening the bottom end, it reduces cooling capacity.

Look carefully through the welch plug holes and you’ll see the top of the grout. This is mainly a drag racing modification, used to stiffen and strengthen the entire bottom end

STEEL MAIN CAPS

Replacing the factory cast iron main bearing caps with high-strength steel versions will also shore up the lower reaches of a block. Most steel main caps are four-bolt, so two-bolt blocks will have to be machined to accept them. Some say the versions with splayed outer bolts are better because the outer bolts are directed into the thicker metal of the pan rails. While that is sound engineering, it has to be said that both styles work well.

Buying and fitting five steel main caps gets expensive; it’s another reason to consider an aftermarket block, such as the SHP Dart types. Although the cheaper versions feature cast caps, they are still four-bolt and the block itself is significantly stronger than the factory piece.

That’s fine with American V8s as there are plenty of aftermarket blocks to choose from — even repro Clevelands are available. But it’s not the case with the Holden V8. One option is the alloy Big Paw from Torque Power (www.torquepower.com.au) that combines Holden components with a Chev crankshaft, timing covers and related performance components. It has Holden engine mounts, so it slips straight into local streeters.

When a stroker kit is fitted, it’s common for the crank and rods to hit or pass quite close to the block. If there’s insufficient clearance, the block’s skirt must be relieved (arrows) via grinding

STUD GIRDLES

A stud girdle reinforces the lower reaches by rigidly linking all of the main caps (and webs) together, increasing the strength of the entire assembly. Some engines are better designed and inherently stronger in the bottom end than others because of extended pan rails — the LS series and Chrysler V8s are good examples. But even these engines benefit from stud girdles in high-performance applications. As well as increasing the general and torsional rigidity of blocks, stud girdles are claimed to help prevent cap movement (walking).

While boring a block isn’t particularly unusual, it’s part of any performance rebuild and opening out bores for increased displacement certainly qualifies as custom work

ALIGN BORING

It’s essential that the main tunnel (the holes through the main bearing caps and webs) is properly aligned and perfectly round, as the decks, cam tunnel alignment and lifter bore placement are all referenced to it. To achieve this, it can be bored or honed — or both.

JSR’s BHJ Line Boring Fixture ensures the cam tunnel is exactly where it should be. BHJ has jigs for accurately positioning everything in most popular motors but they’re expensive

If you fit aftermarket caps you’ll have to bore the tunnel to ensure alignment. The finish left by a line borer doesn’t transfer heat as effectively as the smoother finish created by a line hone, so in high-performance applications, the block is honed after being bored. If you’re sticking with the factory main caps, a line hone will probably be sufficient.

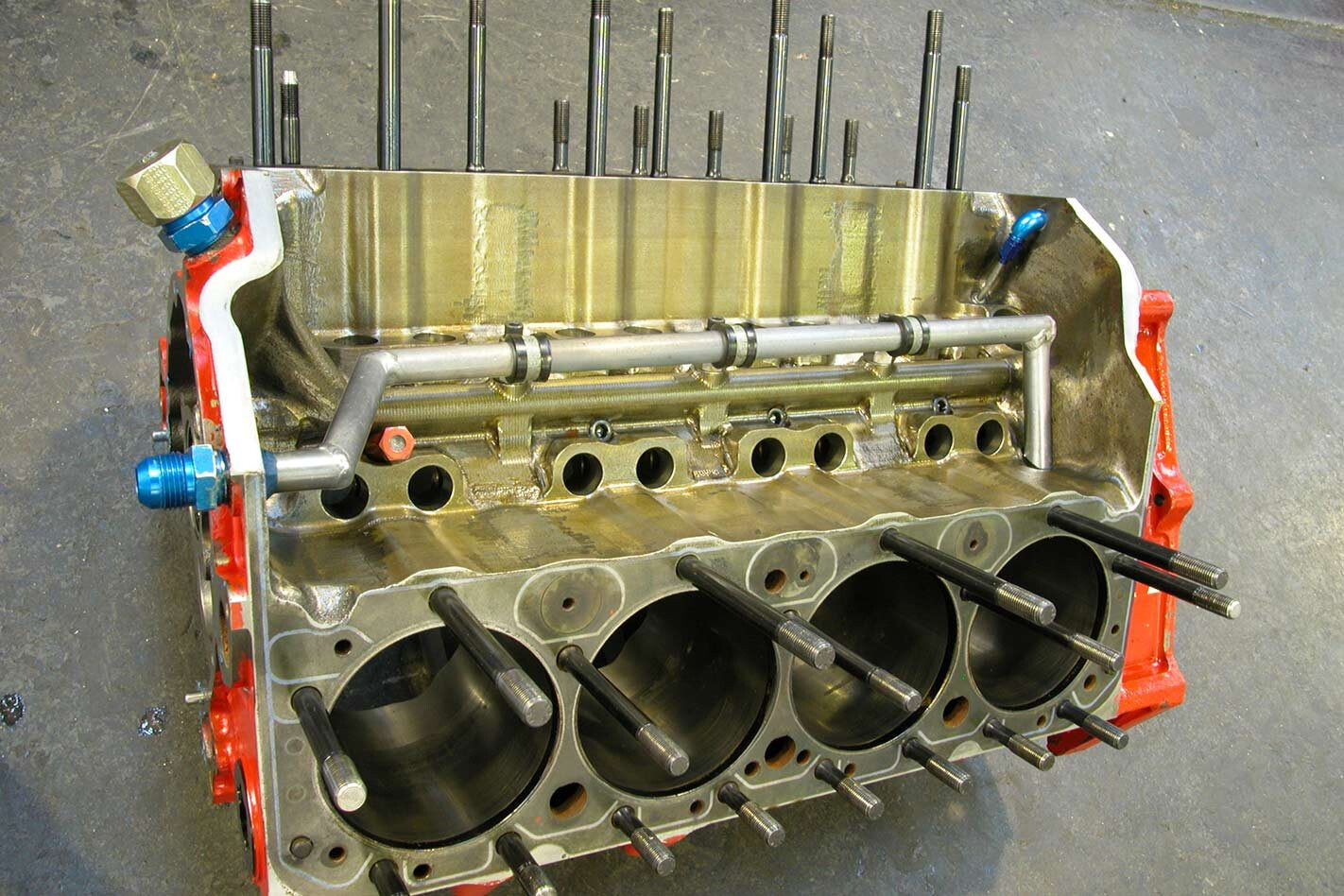

Note how much the standard cam tunnel has to be opened to take roller bearings. The red fittings (top) allow crankcase pressure to be relieved while preventing oil from the valley flooding the cam

CAM TUNNEL

When GM bored the cam tunnels in iron small-block motors, it apparently did it from both ends, which leads to alignment issues. Mick says that many years ago they saw a couple of engines that picked up on the cam bearings and spun them. Align-honing the cam tunnel is the best way to avoid this.

Cams for higher performance engines are often run in roller bearings set in blocks with enlarged cam tunnels. This reduces friction, which can become considerable with a heavily sprung valvetrain. JSR does this work in a BHJ Line Boring Fixture, which ensures everything is in exactly the right place.

While not typically a custom modification, decking the block is an important procedure to get right. It must be flat for optimum sealing, and accurately aligned with the main bearing tunnel from end to end

SLEEVED LIFTER BORES

Once the cam is in the right place, the next step is ensuring the lifter bores are correctly positioned. Mick says this isn’t a problem in most aftermarket blocks but with a factory block they may open the bores, fit bronze liners and bore those in the correct positions.

The main reason for sleeving lifter bores in factory engines modified for high performance is for oil control. Holdens and Chevs tend to send too much oil to the top end, so inserting sleeves with smaller oil transfer holes is a good solution, though it’s best suited to race engines that are regularly inspected.

Some high-end race engines have sleeved bores due to the use of solid roller keyway lifters. To stop them rotating, these lifters employ a pin that rides in an index slot milled in a bronze lifter bushing. This set-up reduces valvetrain mass by eliminating the tie bar or dog bone typically used with roller lifters.

Because oil ends up at the rear of an engine in a rapidly accelerating car, this pick-up for the external oil pump is plumbed to collect it from the rear of the valley. Note that the standard oil drain holes in the valley are blocked to keep oil off the roller cam, which requires less lubrication than a flat tappet cam

OILING MODS

Many engines have less than ideal oiling systems; Clevelands are among the worst. Any Cleveland built for racing needs a supplementary oiling system that takes oil directly from the pump and feeds it to all of the main bearings. There are also various restricter kits to keep excess oil out of the top of the motor and down in the crank where it’s needed most. Oiling systems that feed the mains directly are widely thought to be best.

Holdens and Chevs also suffer over-oiling to the valvetrain, particularly if they’re fitted with roller rockers. In addition, Holdens have restrictive drain holes in the heads and there isn’t much room for draining through the pushrod holes.

A custom-made stud girdle fitted across the mains on an extremely high-performance turbocharged Ford six-cylinder at Nizpro. Note the reliefs (arrow) to clear the conrod big-ends

CRANK SCRAPERS

At 6000rpm, your crank is rotating 100 times each second. Smokey Yunick described the mass of oil whipped up by this action as being like a tangled mess of airborne, energy-sapping toffee. The spinning crank also creates windage pressure, which can keep oil up in the valvetrain. Well-designed sumps minimise these effects but they’re for another story. However, a crank scraper can reduced windage and help oil return. A crank scraper is a metal plate shaped to just clear the rotating assembly of the crankshaft and conrods.

Painting is time-consuming and must be done perfectly, with all unpainted surfaces masked off. Painting works best when all the rough and restrictive edges are ground away beforehand

PAINTING/POLISHING

Anything that assists oil flow back into the sump is good. This is why blocks are sometimes polished and often painted internally. An internally polished block looks beautiful but it’s a great deal of hard work. Painting improves flow to a similar degree and is much easier to do. Of course, ordinary paint is unsuitable as engine heat would cause it to flake off and circulate with the oil, creating blockages. Armature paint designed for use inside electric motors is the best type to use as it stays put when preparation is immaculate.

Though painted and polished internal surfaces undoubtedly help, we’ve never heard of any testing that quantified the benefit. Mick suggests it’s probably minimal because for painting to work all the rough edges have to be ground away first, and by the time that’s done it’s probably enough to improve flow by itself.

O-rings are used in conjunction with copper head gaskets in severe applications. The O-rings must be fitted very neatly with no appreciable gaps where the wire butts up together

O-RINGING

O-ringing consists of cutting a fine groove in the deck of a block and inserting a ring of steel wire that protrudes slightly. When a copper gasket is added and pressed in place by the cylinder head, the steel ring is pushed into the copper, clamping it with extra force at that location and creating a very good seal. O-ringing isn’t so common these days as improved gaskets are now available, such as multi-layered metal types, which serve extremely well in even very high boost applications.

This is a line-honing machine. In normal operation the stones are flooded with coolant but it’s easier to see like this. The stones move back and forth as they rotate

RELIEVING

The rods of a stroker set-up will often hit the sides of the block. Using a die grinder to remove material from the block and create sufficient working clearance is known as relieving the block. Care is needed as it’s very easy to break through to the coolant jacket. That’s a good reason to leave it to your engine builder, despite the fact that it’s a relatively easy task.

These are the main custom modifications applied to engine blocks. Some have been replaced by features included in aftermarket blocks, which are becoming more common as more reasonable prices make them more attractive. But if there’s no aftermarket alternative available, you’ll end up doing at least some of these things to your block.

Apart from generally strengthening the engine’s lower sections, four-bolt caps (steel or cast iron) are said to stop the caps from moving around (walking) in service

Thanks to John Sidney Racing. Give the guys a call on (03) 9544 2553.

(*prices quoted as at 2012)

Comments