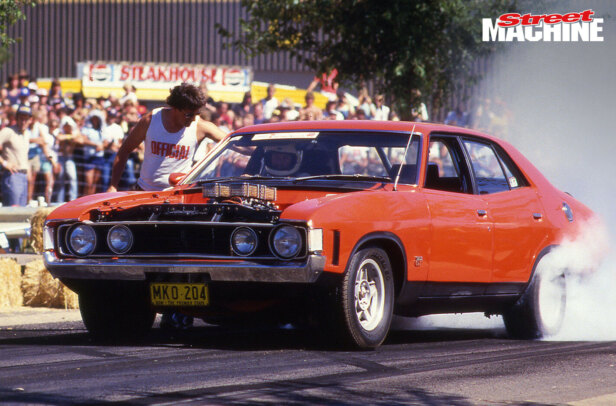

GARY Satara’s OVAKIL was a XC-fronted XA coupe, featured in SM, December 1986.

Our famous give-away A9X kept it off the cover, but it did land the cover of rival mag Performance Street Car in their August/September issue of the same year.

Not only did it look mind-bendingly tough, but OVAKIL was packed with more serious hardware than most Falcon owners could have dreamed of at the time. An Ivan Walker-built blown 351 Cleveland provided the power, but the rest of the package was more of a Pro Touring type deal, with a Doug Nash five-speed ‘box, a fully-floating Harrop rear end, four-spot Jaguar disc brakes and handling fettled by Touring Car pilot Garry Willmington.

The good news, despite rumours to the contrary, is that OVAKIL is alive and well and living in Gary’s garage. Even better news is that the blown 351 that powered the car is now fitted to his Jaguar XJS salt racer, which ran a 224mph pass at the DLRA Speedweek event at Lake Gairdner on Monday, followed by a 236mph run on Tuesday!

We’ll get a full update from Gary when he returns from the salt, but for now, sit back and enjoy the yarn we did on his Jag, as published in the May 2013 issue of Street Machine:

THE PUFF from the LandCruiser’s stack-style exhaust hints at the exertion involved in moving nearly three tonnes from a standstill. Nuzzling up from behind, it noses the bright green Jaguar to a fast jog before the Jag pulls away from the Cruiser’s wooden push-panel.

That parting of bumpers, that initial squeeze of the Jag’s throttle for his first-ever salt run at the DLRA Australian Speed Week will remain an unforgettable instant for Gary Satara.

“I went down there with my mate Paul in 2002,” he explains. In his day job, Gary’s the general manager at transport specialist GMK Logistics but he’s better known to Street Machine readers for his iconic OVAKIL Falcon.

“We’d read stuff about it so we decided to take a look. We flew to Adelaide, hired a car and drove out there. We came over the last rise and there was this great expanse, white and bright and stark, overlaid with all these bright, vibrant salt cars. It was like nothing like I’d ever experienced. Compared to anything else, this was like being on the friggin’ moon.”

So they went again in 2004 and returned home itching to build a car.

“From the day we got back, it was on. My first thought was to take the Falcon down but after seeing what salt can do to a car, I thought: ‘Err, no!’”

Building another Falcon was almost out of the question too, due to the rarity and the spiralling cost— especially when all that was required was little more than the turret, quarters and doors.

Instead he chose to build a Jaguar XJS. You can laugh but it makes sense for a whole lot of reasons, personal and performance.

Gary’s childhood was littered with Pommy cars, including his own first paddock-bashing Austin. On top of that, the Jag was cheap, aerodynamic and something different. And for the first few years of this century, Ford owned Jaguar. Gary’s build mirrors that brand allegiance as he took OVAKIL’s supercharged 351ci Cleveland and dropped it into the XJS. A Ford engine in a Jag? It’s like a Chev in a Holden.

“I could have gone German or Japanese,” he says, “but Jaguar — grace, pace and space. There’s just something about them that I kept gravitating back to.”

Adding irony to his choice is the reputation these old Jags have for rust.

Beating the odds, Gary managed to find a good ‘un for his salt lake project car. “It had no rust at all,” he explains of the forlorn coupe he discovered in a smash repair yard. Not that it mattered much — most of the potentially rusty bits (floors and chassis) were sliced to make way for a purpose-built chassis and driveline.

Hotrods by TJ’s at Camden lowered the lid, the first construction task after Gary stripped it to a shell. The screen and side-glass angles were maintained but those long sweeping rear buttresses required a fair bit of work to take the three-inch cut with aesthetic ease.

Wielded his grinder during the next stages of the build, Gary intended to make the big Jag multi-purpose. With Australian Speed Week held just once per year — if the weather permits — he wanted to be able to take it to events such as Powercruise or the drags for some lairy fun.

However, salt race rules demanded that he cram extinguishers and other safety equipment between the original front crossmember and the McDonald Bros prefabbed rear clip and four-link suspension. That he could work around but a salt car also needs to carry up to a tonne of ballast to keep it planted firmly on the salt, for traction and high-speed stability. That killed the track cruising and quarter-mile considerations.

“I soon realised that it couldn’t go around corners and be a drag car, and be a salt car,” he says. “There’s just too much compromise involved.”

Another compromise Gary had to bear was budget. He’d intended to do as much work as possible himself and only buy in expertise when required. But quotes for the exhaust system — and later, casual chats about the rollcage — soon had him reconsidering the cash.

“I got some quotes to do the extractors and it was around $2500,” he says. “Fair enough; I respect the effort involved in building them but my reality was that if I was to take this car to the salt, I would be doing all the work myself — I didn’t have a choice. I knew how to weld so I got stuck into it.”

It was eight years of evening and weekend effort. Helping the whole way was his father, Boris, who weighed in with all the turning and machining.

“Dad was a tool-maker by trade but he left that when he was 18. When I decided to do this, I bought a secondhand lathe and mill and he got right back into it again!”

Mechanically, the car is tough and simple, carrying the ex-OVAKIL blown and now MoTeC-injected 351ci Cleveland and making 868hp at the treads. Behind it is a Doug Nash five-speed — most salt cars have manuals to keep the delivery of urge consistent — and a 2.5:1 spooled and braced nine-inch from Craft Diffs.

The ballast is significant. The front crossmember carries around 70kg of lead, molten metal poured and set into place. The sills carry lengths of hollow structural steel — each cleverly adjustable for fore and aft location — filled with lead shot. And there’s a ballast box under the rear too.

The rear was fine thanks to adjustable coil-overs but with nearly 600kg going into each front tyre and a tight ride height over standard front suspension geometry, Gary needed an incredibly strong, short stroke spring.

“I asked at a suspension place and the bloke behind the counter said: ‘Sure, bring the car down and we’ll take a look!’ He didn’t understand the fact that I needed to get springs made to a measured specification, not ordered from a catalogue.” He laughs now but at the time, just two weeks before the event, it wasn’t funny.

Eventually, Gary and Boris found an old-school spring maker who wound up a set of stout coils. That happened just days before the car was dynoed, wheel-aligned and loaded for the trip half-way across Australia.

The big green Jag blew plenty of minds at the event even before its first run, which almost made the work worthwhile. “Now, looking at the pictures on my computer, it’s surreal: ‘Wow! That’s my car!” Gary says.

“You’ve really got to put your mind to it. It’s the sort of stuff you think about at night; you think about it when you shouldn’t — like when you’re out for dinner with your wife! It can become quite overwhelming. You need passion to do this. It must boil inside you.”

Comments