We say farewell to Eddie Thomas, the gentleman racer with a lifetime of firsts

THE beaming, round-faced man in the photograph looks like he could be your elderly uncle, or maybe someone you knew once who worked in a bank. He wears a neatly adjusted tie and a white collared shirt, and his overalls, also white, are immaculate. Surely this is no motorsport daredevil.

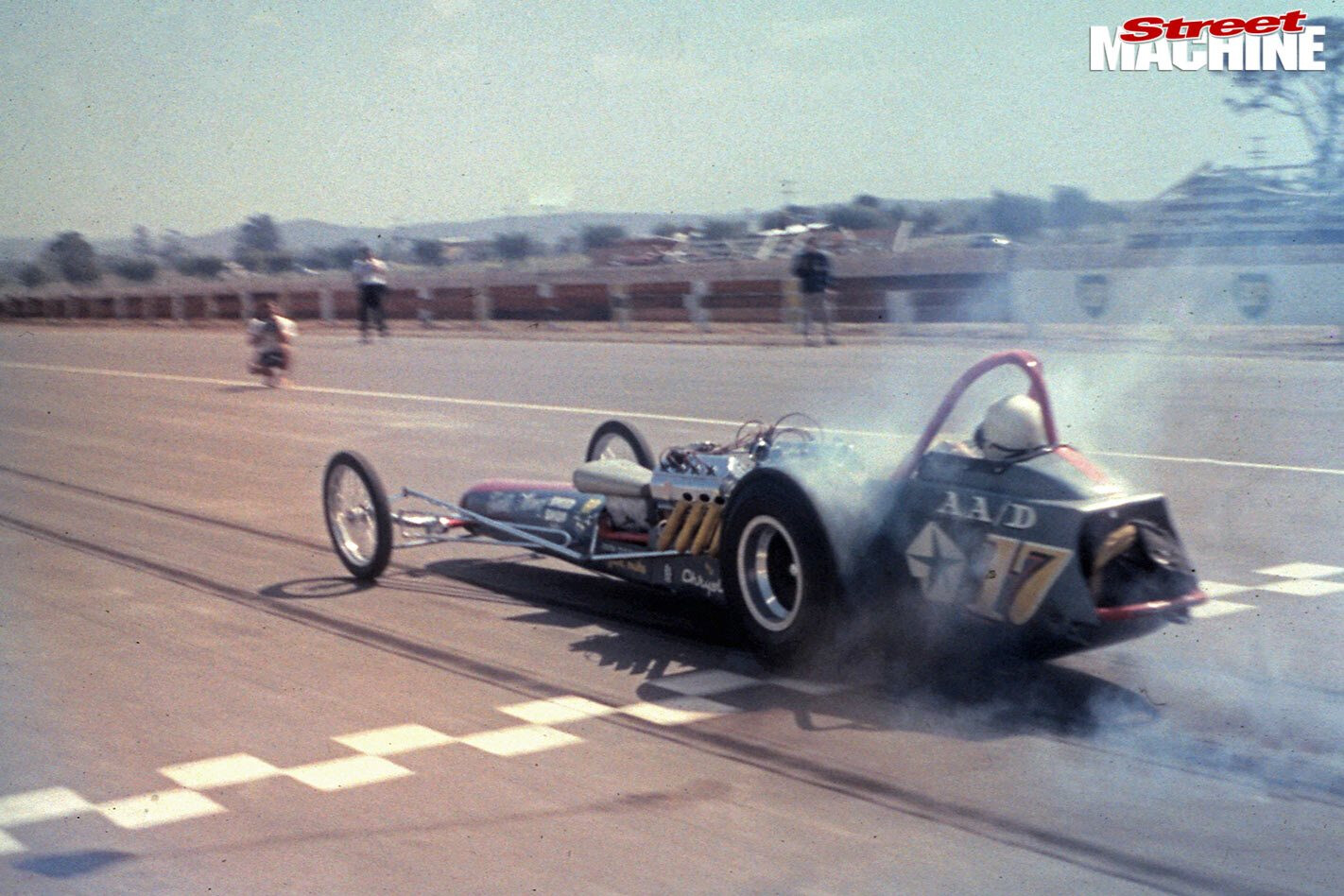

Eddie Thomas at the 1968 Nationals at Calder Park, where he ran a career-quickest pass of 8.55 in the shed-built blown Hemi-powered dragster dubbed Old No.17

Yet he sits in front of a primitive rollbar, with a dragster’s cowl in front of him, racing slicks either side. On the edge of the photo you can just glimpse the back of a Chrysler wedge engine.

This is none other than Eddie Thomas, and his many nicknames – ET, Big Daddy, Fast Eddie – hint at his achievements. Despite a brief racing career of just four years, Thomas was one of the most significant figures in the birth of the speed equipment industry in Australia and in the earliest days of Australian drag racing. His impact on the sport and its participants continued long after he’d ceased racing, helping to lift a foundling motorsport out of its infancy and on a path towards the professionalism it enjoys today.

Thomas began racing almost as soon as could earn a wage, buying a motorcycle and going scramble racing – an early form of motocross – around his home in Melbourne. He soon graduated to speedway competition at the Aspendale track and other venues around Melbourne.

The Second World War interrupted his racing when he enlisted in 1942, but after being demobilised in 1945 he was back at it, at sprint races, hillclimbs, road racing and his beloved speedway. He found that he could actually earn a living out of appearance and prizemoney on the dirt tracks, especially after the Maribyrnong Speedway was opened in 1946.

Thomas’s car was powered by a Willys Jeep engine, but as he couldn’t afford all the fancy parts, he started making them for himself, and then for others. What began as a part-time activity in his home garage kept growing to the point that in 1956 he and good mate Pat Ratliff took a lease on a shop on the corner of Dandenong Road and Bourke Road in Melbourne’s Caulfield, trading under the name of Eddie Thomas Speed Shop.

Thomas moved in his home-built camgrinding machine and had soon installed a Heenan & Froude dyno – the first in Melbourne – which attracted all the top teams from all disciplines of motor racing. The shelves were stocked with all manner of go-fast bits from all over the world, and Thomas became one of the first to start issuing his own T-shirts after American drag racer Dante ‘Duce’ Van Dusen stuffed a couple in a shipment of Moon items from the States.

(Left) Eddie has crewman Greg Goddard put his new fire suit to the test. It was all part of the act, but it had deadly serious consequences a few months later when Eddie exploded a clutch and suffered the first drag race fire in Australia

When South Australian-based parts manufacturer Speco put its business up for sale, Thomas jumped at the opportunity and was soon marketing his expanded range of parts under the Speco-Thomas brand.

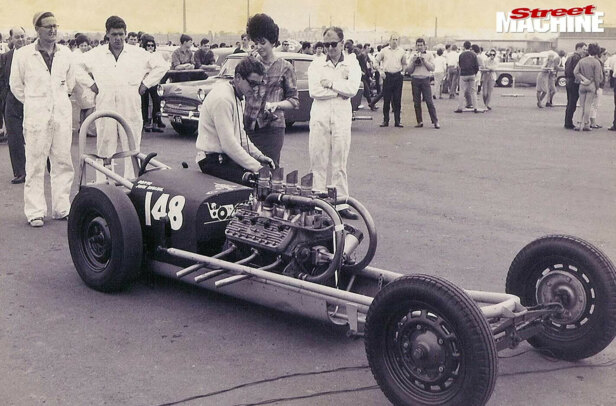

The business’s first employee was young hot rodder Greg Goddard, who had built the nation’s first dragster from crude parts he’d thrown together in 1958, and then made a much more professional effort later in the year with a car built around the sidevalve motor from his ’34 coupe. Eddie had been out to the drag strip at Pakenham to see it in action, but only really became interested when American circuit racer Chuck Daigh was billeted at Thomas’s place in 1962 and explained the popularity of drag racing in the States, stating that it was “the coming thing”.

When Goddard decided to pull the motor from the dragster in 1963 to install it into a speedboat, he left the rolling chassis parked at Eddie’s. A few weeks later, Eddie – now 46, comfortable with the success of his business, and having not raced competitively for a number of years – rang Goddard and offered to buy it.

Eddie deploys the laundry in his first Greg Goddard-built car at Riverside in 1965. Australian drag racing’s very first parachute, Eddie acquired it through a business contact in the USA, dragster racer ‘Dante Duce’ Van Dusen

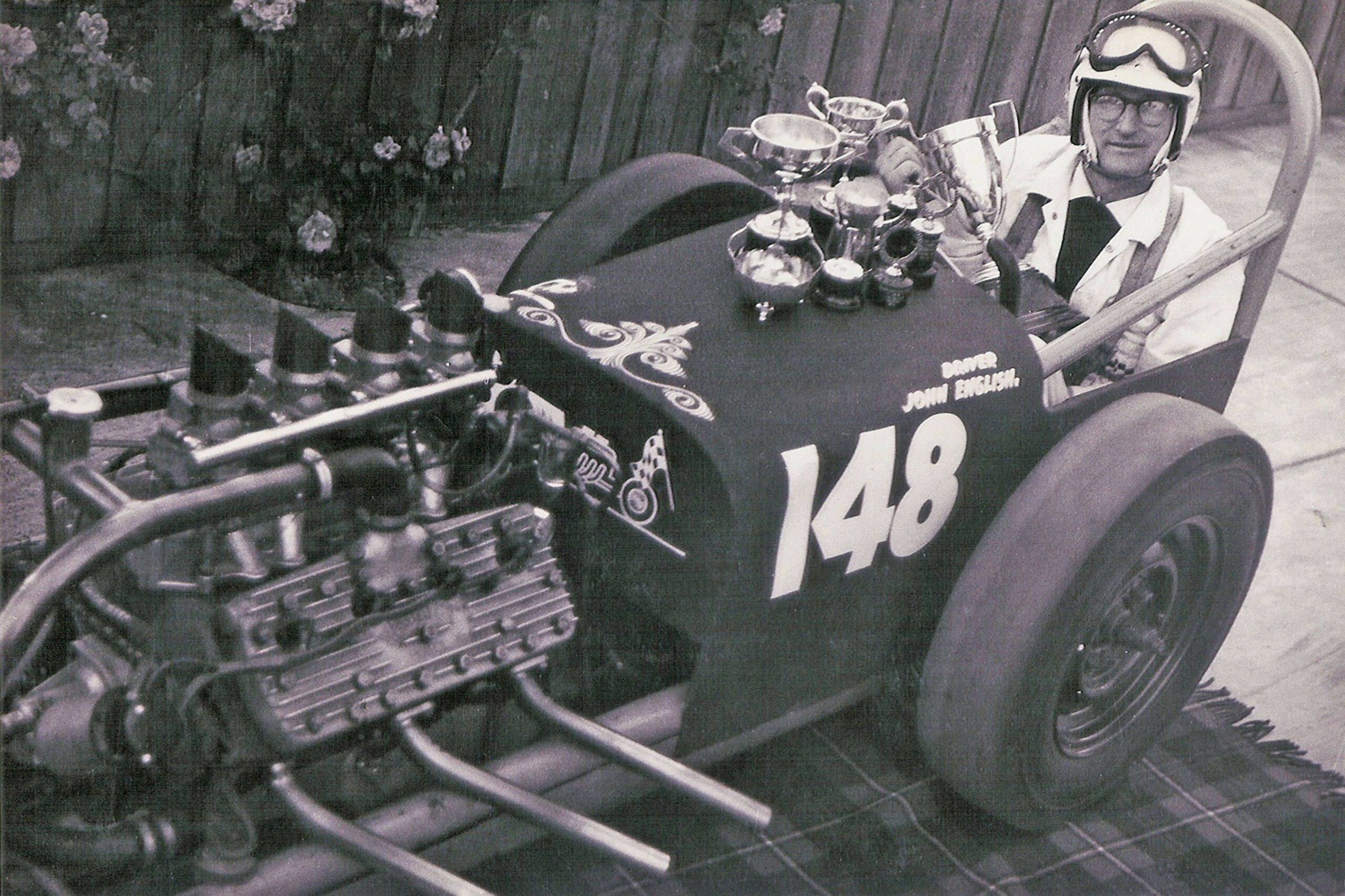

Eddie’s friend John English, a keen racer at the new Riverside strip at Fishermans Bend, needed a car to maintain his lead in the points series at the drags. So Eddie loaned him the car, which English ran with his own sidevalve V8.

In the meantime Eddie had pieced together a 318 Chrysler wedge motor, with a front-mounted Marshall cabin blower, and it was dropped into the chassis with English as the driver. The rear brakes, however, were pretty marginal, and after one pass where the car plunged off the end of the braking area into a nearby swamp, English returned to racing his own car.

Eddie, however, stepped up to the plate and was soon enjoying himself mightily. From May 1964 he began pushing boundaries, going to a track record of 10.74 and reaching speeds over 130mph.

He began to ask questions about parachutes from his US contacts. Again Duce came to the party and sent out a small drag ’chute designed for aircraft, but when that didn’t work out in testing he went to a larger cargo-drop ’chute. It did the job and was the first on a quarter-mile car in the country.

With braking sorted, Eddie turned back to the go-fast bits, switching to a 365 Chrysler. He began closing in on the 10.0-second barrier, and in May 1965 the car broke through the 140mph barrier, running 145mph.

But plainly the old dragster was rapidly being outdated by the 500hp engine, racing slicks and performance expectations. So Eddie bought a set of dragster plans he saw advertised in American Hot Rod magazine, and set about building something a little more up-to-date.

Eddie’s Old No.17 car, when first built in 1965, was the first true US-style dragster in the country. The car was built from a set of plans purchased through a magazine ad, and its handmade aluminium body by Peter Lacey was styled on a car being run by US racer Tony Nancy

The result was a 140in-wheelbase, aluminium-bodied car was based on the Tony Nancy dragster then being campaigned in the USA. It became known as ‘Old No. 17’ for its racing number, and was a huge jump in appearance, technology and performance over anything else in the country. On debut in June 1965 it ran an Australian record of 10.33 seconds, still with the 365-cube Chrysler. In July it went 9.76@150mph, the first car into the nines and over 150mph, a British Commonwealth record. Three weeks later in Sydney it went 9.51.

Eddie in his ex-Greg Goddard dragster in 1965. This car was only the second dragster built in the country, made by a guy who had never seen more than photos in magazines. Its wheelbase was determined by the length of his garage

While in Sydney, Eddie put his car on display at the Sydney Boat Show and saw a 426 Hemi – the first imported into the country – on the Chrysler and decided to buy it. Making 400hp with two carburettors, it had almost as much grunt as the old blown 365, and when fitted up with a front-mounted GM supercharger and a few more improvements it jumped closer to 1000hp and went 9.33 in March 1966.

Eddie and employee Greg Goddard working on the dragster’s blown Chrysler in the dyno room, probably 1965. Eddie’s whop dyno was in high demand in the racing community

But the big deal of that year was the six-event Dragfest tour of Australia that featured six US dragsters. Eddie was contracted to appear at all the events as one of the local heroes. With the new engine ahead of anything even the Yanks came equipped with, Thomas should have been a real player, but aside from one brief blast he never quite got to show what he could do. The first Melbourne event was displaced from Riverside over lease issues and was run over an eighth-mile at the Calder road circuit. The second event, at the brand-new Surfers Paradise track, was on a dusty and unprepared surface, but here Eddie shone with an 8.84-second run, the first local under the nine-second barrier. Then in a race with one of the Americans he charged to 178.92mph, the fastest speed yet for a local, and that was strictly on alcohol fuel, as nitro was a virtual unknown in Australia at the time.

Eddie was a keen speedway racer before he discovered drag racing. In fact, he almost made a living from his racing, and the development of parts for his sprintcars helped launch his speed shop and parts business

Three months after the fire, Eddie was back in action. Now he had the blower on top of the engine, as encouraged by the Americans, who said it would run better that way. When the Riverside track closed in October 1966, Eddie had to wait until 1968 before racing returned near home, at Calder Park. In April that year, with five per cent nitro in the tank, he pushed to an 8.57, followed in October by a best-ever 8.55 at the Nationals, but a broken crankshaft had him thinking about the future.

Eddie recovering in hospitial from his fire in April 1966. The clutch fire would have been much worse had it not been for the fire suit. The trophies are for top speed by a local at the 1966 Dragfest tour and another from the six US racers here for the tour

Eddie had seen fireproof race suits advertised in Hot Rod magazine, made from a 3M material called Mylar. He discovered that 3M in Australia had some in stock, and they offered to donate enough of the material to have a suit made, the first in the nation. American racer Tony Nancy donated a face mask and pair of goggles for Eddie to use. These would come in handy during one of the regular monthly race meets at Riverside, when, near the finish line on one run, the car’s clutch exploded and flames shot up through the cockpit, the first serious fire in Australian drag racing. Appropriately clothed, Eddie managed to bring the car to a safe halt and extract himself from the still-burning car, but he’d suffered severe burns to his hands, neck and ankles. After receiving medical assistance, he was returned to the start line where he stoically answered questions with his usual politeness before being taken to hospital, where he spent eight weeks recovering.

For Eddie it had always been about fun. He’d never won a major title – other than all those firsts – but he didn’t care. He loved chasing the improved times and speeds, essentially racing against himself, enjoying the successes of making new parts, solving problems, overcoming failures. Now racing had started to become serious. There was opposition from the likes of Ash Marshall and Graham Withers; it was becoming expensive to run the big numbers. His business had changed. He wasn’t dealing directly with the racers as he had once done. Now he sat behind a desk and others did the face-to-face stuff.

The race car was sold; the business followed. A year spent working on Repco’s Formula 1 program for Jack Brabham was a welcome respite; then, in 1969, Eddie set up his own general machining company, Redline Engineering, with his son Ken.

Eddie never let the grass grow too deep beneath his always-polished shoes. Long after Ken took the helm at Redline, Eddie would be there tinkering with some pet project. He bought himself a JAP speedway bike and an Offenhauser-powered midget and restored them to within an inch of their lives. But with a rowing level of recognition from those who came after him, acknowledging his pioneering achievements, Eddie’s interest in drag racing was re-ignited. Over the past decade it was not uncommon to see Eddie receiving honours or making appearances in the pits at major drag racing events, peering with interest at drew work or chatting amiably with the emerging stars of the day.

Eddie’s No.17 alongside Ash Marshall’s new Vandal in the fire-up road at Riverside during the first Nationals, October 1965. The pair never got to race at that event after Marshall suffered engine failure, but they soon became regular combatants

Pioneering work aside, if Eddie Thomas was recognised for anything it was his gentlemanly demeanour. And if there was any single souvenir that summed up Eddie Thomas and his drag racing career, it was a trophy that the six visiting American racers of 1966 chipped in to buy and present to him. It reads simply: “To eddie Thomas, Australia’s gentleman drag racer, in appreciation of your assistance.”

The fun finally ceased for Eddie on 10 November 2017, when he passed away at age 99. RIP Eddie.

Comments