This article was originally published in Street Machine’s Hot Rod magazine, 2007

THE Yanks like to call these types of hot rods survivors — so named because they somehow managed to escape the fate of many others that were wrecked, pulled apart, or the most ignominious fate of all, turned into a street rod!

Nope, this car is just perfect as it is, practically unchanged since it was finished way back in 1965 by a young bloke called Peter Swift with a lot of help from his mate Eddie Ford and father-in-law Allen Sainsbury.

Swifty had a good idea of what he wanted; but, of course, what he ended up with was nothing like it. The pair filled many days and covered many miles looking for a ’32 Ford five-window coupe, but no-one ever mentioned that they never came to Australia. What Eddie and Peter did find was a stuffed Model T truck from which they salvaged the cowl, firewall and windscreen posts.

“As we had been unable to find any other Model T parts, I decided to store it away and use it if nothing better could be found,” says Peter. More searching unearthed a burnt firewall and doors, and the back seat section of a Model A Tourer.

The next pieces of the puzzle were to find a chassis and an engine. Peter managed to turn up a Model A chassis at the local wreckers and then scored a ’48 Mercury flathead for the princely sum of £15.

The finned Edelbrock rocker covers are very hard to find these days, second only to the Edelbrock P600 tri-power intake. The distributor is a Du-Coil unit that runs two separate four-cylinder circuits utilising two Lucas coils. Those little rubber things keeping the plugs wires neat are Elastrator rings. They’re usually used for marking calves and lambs. No billet here!

Peter had an idea of what he wanted after spying Marty Holman’s T-Bucket on the cover of the March ’61 issue of Hot Rod, but he wanted his to sit a lot lower. “I reckon you could drive over a wombat with Marty’s car, it sat so high, so that’s why my car has such a vicious channel,” he says.

With all the body parts tacked together and perched on top of the frame, it was pretty clear that the proportions weren’t right. In the end, the body was channelled nine inches over the frame. Of course, these days people get hot rods super low by modifying the chassis, but Peter has an explanation why they didn’t take that route: “Back then we didn’t know anything about C-ing or Z-ing; people weren’t doing it back then.”

To get the car as low as possible, Peter made changes to the chassis, including the replacement of both crossmembers. “The front member was replaced with a pipe which had a bracket to take the front spring; the arched rear crossmember was replaced with a straight one made from angle iron sections welded together,” he explains.

Both front and rear springs also had their eyes reversed and a few leaves removed to reduce the spring rate a little.

The ’46 Ford axle hangs off a suicide perch and is located by homemade hairpins. Add chrome tube shocks and backing plates and you’ve got the ideal T-Bucket front-end

With the basic stance of the car looking pretty good, the various bits and pieces of the body had to be joined together somehow. Round tube — square wasn’t available back then — was used to create a framework for the cowl and body, and as the body didn’t come with any hinges or locks, the doors were welded shut and effectively used to join the front and rear of the body together. Eventually all the big dents were knocked out and some new-fangled stuff called fibreglass was used to fill up the gaps.

Whatever they did it seems to have worked, as the paint on the car now is the same Dulux black enamel Eddie Ford sprayed on with a vacuum cleaner — running in reverse. Eddie also adorned the car with some simple pinstriping, but his contribution went much further.

Stitched up more than 40 years ago, the diamond-tuft interior still looks awesome. The dash has a full complement of gauges and the wheel is a 14-inch Covico item. Nope, we’ve never heard of them either!

“Eddie did as much work on the T as I did,” says Peter. “He had a workshop with a pit, an oxy welder and a stick welder, as well as a drill press – we were pretty lucky. We built his chanelled ’34 five-window coupe alongside my T in that same workshop,” he says.

Things were a lot different back then, and you couldn’t just go down the road and buy stuff off the shelf: “Every little piece and bracket on that car was made with a cut out with a hacksaw and then filed by hand. We didn’t have angle grinders back then.”

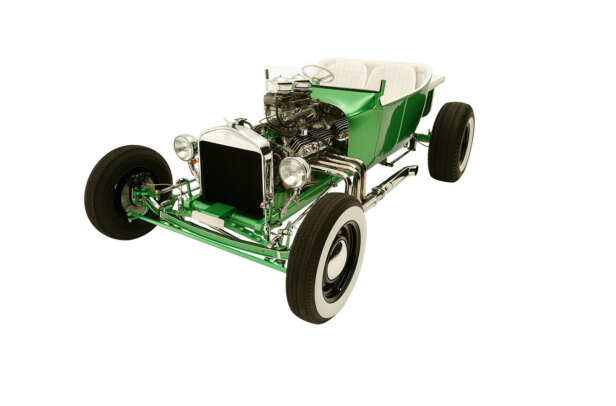

Even something as simple as a set of wheels turned into a major project. Peter had sourced a set of 16-inch wheels, but as we’ve discovered, he wanted his hot rod to sit nice and low. “There was a place in Melbourne called Austral Wheel Works. I took my wheels down there one Saturday morning and told them to knock two of them down to 13-inch and then asked for the fattest they had in a 14-inch for the back. They said they had a set of six-inch wheels that had been brought into Australia for Norm Beechey’s ’61 409 Impala,” says Peter.

These were wrapped in wide whites all round, measuring 14×6.40 up front and 14×8.00 on the rear – “The biggest I could get at the time”, says Peter. The fronts have since been changed but, incredibly, the rears are the wheels that went on the car in 1963.

You’ve probably picked up by now that the flathead we’ve mentioned is not what’s sitting between the chassis rails these days. Partway through the build Peter came across a 318 Poly motor.

It’s basically standard, but does sport an Edelbrock P600 tri-power intake (bought from the Eddie Thomas Speed Shop) with a trio of Stromberg 94 carbs.

Not only did Peter’s car take out Top Roadster and Best Engineered at the 1965 Victorian Hot Rod Show, but it also graced the cover of Modern Motor in February 1966

Apart from the Edelbrock rocker covers — try finding another set of those — and the Du-Coil distributor, the only other deviation from stock are those wild pipes. Originally Pete had four individual pipes, each with their own baffle.

“It was just too loud, even though there was no EPA back then. Now the four 1½in pipes go into a hot dog muffler and then the tip of a four-inch truck stack,” explains Peter.

Shifting gears is still left to the old ’39 Ford crash box, which required the creation of a steel bellhousing to adapt to the Dodge motor. This fancy bit of gear was built by Clarrie Armstrong Engineering in Castlemaine. More fiddling was required to get the rest of the drivetrain connected as the very short wheelbase of the Bucket meant that the torque tube and driveshaft had to be shortened from six feet long to a measly two feet six!

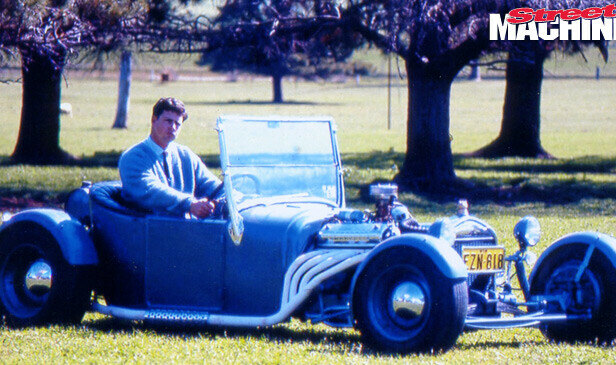

An early shot showing all the major components in place. Most interesting are the axle stands. Peter and Eddie didn’t drink – they spent all their money on cars – but every Sunday morning they’d go for a drive and pick all the empty tinnies. Back then you could get cans that held as much as a longneck, and if you found eight you could weld ’em up to make a handy set of stands

The trim is simple, but instead of the usual tuck and roll, Pete had Merv Hall in Castlemaine stitch up a diamond-tufted red vinyl interior. “I really wanted to use red naugahyde as the Yanks did, but apparently there was a chronic shortage of naugas in Australia,” says Peter. Ah, it’s an oldie but a goodie!

The dash was filled with a collection of VDO, Smiths and Stewart Warner gauges and finished off with some red carpet. In an early example of recycling, Peter cut an ammo box into halves and welded the pieces either side of the torque tube. One side holds the battery, the other is for tools.

A young Peter Swift with an early mock-up of the car. Notice it still has the Mercury flathead in place, so this would be prior to December 1962 when Peter got hold of the Dodge Poly motor

Peter admits there is a secret to the T-Bucket’s longevity: “I finished building the car in 1965. It won Top Roadster and Best Engineered at the Victorian Hot Rod Show that year, but I never got it licensed until 1977, when I took it to the nationals.”

He did have a reason though. The motor wasn’t running right and on pulling it apart he discovered one of the pistons had a hole in it. “The car sat in the shed pulled apart for years. I got involved in competition water skiing and I’d practically forgotten about it. Some guys had gone to the first nationals in Narrandera back in 1973 and were keen to buy a hot rod. They heard about my car and offered to buy it. I would have sold it, but my wife Bubby said, ‘Don’t you dare! They’ll fix it up and you’ll see it cruising down Barker Street in Castlemaine. You’ll regret it.’”

The classic T-Bucket formula – big engine, short wheelbase, lightweight body. By this stage Peter has had the 16-inch wheels cut down to 13-inch fronts and 14-inch rears – those gloss black wheels and baby Moons are the perfect finishing touch

So with the help of a Dodge workshop manual and his father-in-law, Peter put the motor back together and it worked. That was in 1977, just in time for the third Hot Rod Nationals. “It was a new car, but already 15 years old,” Peter jokes.

Well, it’s more than 40 years old now, and although it wears a few extra wrinkles and may not be quite as shiny as it used to be, it still looks as good as it ever did and is one of the coolest T-Buckets ever built in Australia, possibly the world.

PETER AND BUBBY SWIFT

1924 FORD MODEL T BUCKET

Colour: Dulux Black enamel

ENGINE

Brand: 1960 Dodge Poly, 318ci

Induction: Edelbrock P600 tri-power with three Stromberg 94s

Heads: Standard

Camshaft: Standard

Lifters: Standard solid

Pistons: JC Whitney specials (cheap!)

Rings: JC Whitney

Crank: Standard

Fuel pump: Standard

Cooling: Custom-made by Ron Twitt

Exhaust: Four-into-one headers with hot dog and 4-inch truck stacks

Ignition: Du-Coil distributor with twin Lucas coils

TRANSMISSION

Gearbox: 1939 Ford

Diff: 1940 Ford Banjo with 3.78 gears

Tailshaft: Very much shortened torque tube and driveshaft

Clutch: 11-inch Dodge truck clutch and pressure plate

Bellhousing/Adaptor: Steel adaptor built by Clarrie Armstrong Engineering

SUSPENSION AND BRAKES

Springs: ’48 Ford with reversed eyes and leaves removed (f), ’40 Ford with reversed eyes and leaves removed (r)

Shocks: Gabriel chromed (f & r)

Steering: ’38 Chevrolet steering box and column

Brakes: ’48 Ford (f), ’40 Ford (r)

Master cylinder: ’56 Customline

INTERIOR

Seats: Custom built

Steering wheel: 14-inch Covico

Trim: Diamond-tufted red vinyl

Re-trimmed by: Merv Hall

Instruments: VDO, Smiths and Stewart Warner

Shifter: ’39 Ford

Seatbelts: Hemco lap type

Stereo: Wouldn’t be able to hear it if I had one!

WHEELS AND TYRES

Tyres: 13×6.40 Goodyear crossplies with flapper whitewalls (f), 14×8.00 Firestone whitewalls

Wheels: ’48 Ford centres on 13×4.5in Holden rim (f), ’48 Ford centres on 14×6 rims

Comments