FWH, RTM, PTO, LSD. What does any of that mean? If the last one was changed to £/s/d (pounds, shillings and pence, avoiding any possible reference to the psychedelic 60s) would that help?

Back on February 14, 1966, when Australia changed from ‘imperial’ currency to dismal guernsey, recreational 4WDing here was in its infancy – it hadn’t even graduated to pull-ups – but by the mid-70s it was burgeoning to become a major outdoor activity. However, it was a vastly different scene than it is today.

In mainstream 4WD vehicles, with the notable exception of the two-door Range Rover released at the 1970 Paris Motor Show, all were part-time four-wheel drive. Early Land Rovers, for example, had three transmission sticks to play with. One was for 4WD engagement, one was for low range, and the other was, of course, the gearstick. From memory, they all had different coloured knobs to avoid confusion.

Quickly supplanting the Land Rover as vehicle of choice, the Toyota Land Cruiser made do with two, with high and low range being engaged with the same lever. However, engaging low range took careful consideration because often you’d often have to reverse for what seemed like miles (as distance was measured in those days) to disengage it.

Often, the vehicles were fitted with permanently engaged front axles, which had owners scrabbling to fit aftermarket FWHs (free-wheeling hubs), supposedly to enjoy fuel savings created by no permanent mechanical drag on the front axles. So you’d see drivers leap out before obstacles to engage the hubs, and repeat the performance afterwards to switch back to ‘Free’, terrified that if they remained in ‘Engage’ they’d have axle splines flying all over the place. An army mate of mine told me that ADF vehicles fitted with FWHs were often left in ‘locked’ to keep the axles lubricated, and so I drove thousands of kays in my BJ40 with the hubs engaged, never once standing on the side of the road with my thumb out.

Often, the vehicles were fitted with permanently engaged front axles, which had owners scrabbling to fit aftermarket FWHs (free-wheeling hubs), supposedly to enjoy fuel savings created by no permanent mechanical drag on the front axles. So you’d see drivers leap out before obstacles to engage the hubs, and repeat the performance afterwards to switch back to ‘Free’, terrified that if they remained in ‘Engage’ they’d have axle splines flying all over the place. An army mate of mine told me that ADF vehicles fitted with FWHs were often left in ‘locked’ to keep the axles lubricated, and so I drove thousands of kays in my BJ40 with the hubs engaged, never once standing on the side of the road with my thumb out.

Driving long distances in these early vehicles quickly proved they’d been designed for short-haul agricultural, military and mining applications; not a comfortable private-owner touring experience. An early-1980s twelve-hour trip from Sydney to Enngonia (100km north of Bourke) in a four-cylinder diesel Land Rover proved the point. Max speed: 80km/h. Air-con: two manually operated dash vents. Seats: two flat cushions on metal bases. Steering: non-assisted. Engine noise: deafening. A photographer trying to treat a cold by constantly chewing stinking garlic pills, midsummer heat and a locust plague added to the glorious experience. Ah yes, those were the days.

Truck-derived suspension consisting of leaf springs and beam axles contributed to the problem, designed for toughness and longevity rather than ride quality. Independent suspension companies quickly sprang up, using techniques like progressive rate springs and multi-valved shock absorbers to civilise ride. After having an Old Man Emu aftermarket suspension fitted to my 60 Series Cruiser in the early 80s, I swore it rode like a Range Rover (almost).

Another factor was tyres. In the early days, there was very little choice in 4WD tyres. Military-style bar treads were an option for those who had absolutely no intention of driving long distances. Jeep Service were another largely agricultural alternative, and Toyotas came standard with 7.50x16 RTMs (Dunlop Road Trak Majors), a tyre with such a distinctive on-road howl that you could pick a Cruiser coming from blocks away.

Another factor was tyres. In the early days, there was very little choice in 4WD tyres. Military-style bar treads were an option for those who had absolutely no intention of driving long distances. Jeep Service were another largely agricultural alternative, and Toyotas came standard with 7.50x16 RTMs (Dunlop Road Trak Majors), a tyre with such a distinctive on-road howl that you could pick a Cruiser coming from blocks away.

All were cross-ply construction – a quick Q&A around the rec room of the Shady Rest 4WDers’ retirement home came up with the consensus that the first 4WD radial was the 7.50x16 Olympic Steeltrek (Frank Beaurepaire’s Olympic Tyre Company merged with Dunlop in 1980, so it probably appeared before then). All these tyres ran on split-rim steel wheels, and it was the devil’s own job to break the bead on these if you had a puncture. Farmers could lower a grader blade on them, and some of us actually drove over the edge of the tyres to get the flat off for repair.

15-inch well-based rims came next. By far the most popular of these were the Sunraysia brand; designed, developed and manufactured here in Australia by a bloke called Neville Harlow. Initially, serious remote-area travellers steered clear, knowing the chances of picking up replacement rubber in the sticks was equally remote. But Outback tyre suppliers quickly started stocking the new size, and practically everyone ran 15s in no time at all.

Choice of brands was pretty good, but they were all mainly all-terrain patterns picked for good wear characteristics rather than any particular feature – there certainly wasn’t the degree of specialisation (mud grubbers, rock hoppers) we see today. Magnesium alloy rims started appearing around the same time, prompting spirited campfire debates of pros and cons. They were certainly lighter, contributing to better unsprung weight, but if you bent one climbing rocks you couldn’t hammer it back into shape as you could a steel rim.

.jpg ) Serious 4WDers drove diesels. Not only were they less exposed to engine failure than petrol engines during water crossings, but the extra engine braking afforded for steep descents was a major plus. Longer range – a major consideration for true Outback tourers – was another attraction. Autos – archaic three-speeders in the main – were avoided because of a complete lack of engine braking downhill, necessitating constant use of brakes (something that’s avoided just as much today).

Serious 4WDers drove diesels. Not only were they less exposed to engine failure than petrol engines during water crossings, but the extra engine braking afforded for steep descents was a major plus. Longer range – a major consideration for true Outback tourers – was another attraction. Autos – archaic three-speeders in the main – were avoided because of a complete lack of engine braking downhill, necessitating constant use of brakes (something that’s avoided just as much today).

There were no disc brakes. All were drum types, meaning that after any half-serious water crossing, you’d have to accelerate away while depressing the brake pedal to dry things out. If you didn’t do this, there’d be zero retardation when you next really needed it.

Recovery equipment was limited to towropes and winches. Forget snatch straps; they didn’t exist. No Dyneema ropes, either. Winches used wire ropes, and in the very early days were PTO (power take-off) types. Because of their military and agricultural heritage, all early Cruisers (as an example) had PTO outlets coming out of the transfer case, and if you knew what you were doing, PTO winches were great.

By using the gears a variety of winching speeds were possible, but the winches were prone to breaking shear pins, and if your engine was kaput, so was the winch. Probably for weight- and cost-saving reasons, PTOs were dropped from manufacturing specs, bringing the electric winch to the prominence it enjoys today; though some aftermarket suppliers experimented with hydraulic and capstan winches along the way.

Communication with the outside world was difficult. This was a good thing. You could say to the office ‘I’m heading off to the desert for three weeks and won’t be contactable’. Mobile phones didn’t exist, so once you strapped yourself in for the journey, the peace began; the only means of comms were RFDS radios – Traeger systems that involved stopping, throwing an aerial over a relatively high tree branch, and fishing around for a frequency connection. Then came Codans (really complicated to use) followed by sat-phones (which should be banned).

Communication with the outside world was difficult. This was a good thing. You could say to the office ‘I’m heading off to the desert for three weeks and won’t be contactable’. Mobile phones didn’t exist, so once you strapped yourself in for the journey, the peace began; the only means of comms were RFDS radios – Traeger systems that involved stopping, throwing an aerial over a relatively high tree branch, and fishing around for a frequency connection. Then came Codans (really complicated to use) followed by sat-phones (which should be banned).

Even back in 1996 when I was leading the Land Rover Calvert Centenary Expedition I was receiving, via sat-phone, faxed minutes of the board meetings back in Sydney – as if I could do anything about it in the Gibson, Little Sandy and Great Sandy Deserts. Sat-phones were pretty primitive then, requiring setting up a dish which you rotated to pick up satellite signals. Unfortunately, it’s now much easier.

Creature comforts like in-car entertainment were virtually non-existent, AM-only radio offered all the sound quality of a blowfly trapped in a pickle bottle, and there were no buttons to push for station selection. Battling steering that had its own idea of where the vehicle should be going, while fiddling with a dial to find a decent radio programme, was a game of Russian roulette that I’m glad has long gone. And, of course, aftermarket suppliers sprang up to fill a void. If you were flash (and flush enough) you could get a decent radio with an integrated cassette player. The Pioneer system I fitted to my BJ40 was ‘the duck’s guts’, as we used to say.

OE seats obviously designed by greedy chiropractors were another suitable case for treatment. Ed Mulligan’s Opposite Lock sold Aussie-made Stratos seats, and not being able to afford the aristocrat of automotive aftermarket seat – Recaro – I settled for Scheel seats in the Cruiser. These made long-distance travel a far more civilised experience, with plenty of lateral support and more padding.

Night driving was a dodgy experience with OE lighting. Headlights were still measured in candle power, but it didn’t take too long to count the candles. In the early days, aftermarket lighting came straight from rally cars, with French-made Cibié and Marchal being the picks with little else to choose from; though a mate of mine settled for an aircraft landing light to help avoid nocturnal grasshoppers. Lighting around the campfire was pretty primitive as well.

Night driving was a dodgy experience with OE lighting. Headlights were still measured in candle power, but it didn’t take too long to count the candles. In the early days, aftermarket lighting came straight from rally cars, with French-made Cibié and Marchal being the picks with little else to choose from; though a mate of mine settled for an aircraft landing light to help avoid nocturnal grasshoppers. Lighting around the campfire was pretty primitive as well.

The BJ did offer a work-light that was hung under the bonnet, but torches looked after the rest of night-time navigation. Maglites and Dolphins were the favourites, with head lamps only coming onto the scene in the late 80s. An early convert, I tolerated the giggles and jokes about being the resident Martian, but they wore thin very quickly, and disappeared once everyone was wearing them. Camp lighting was originally provided by kerosene lanterns, known generically as ‘Tilley lamps’, named after John Tilley, the Pommy inventor of the hydro-pneumatic blowpipe that made the whole thing work.

The lamps were pumped to build up pressure in a reservoir, and then a mantle (made of chemically treated silk or more commonly, rayon) was lit and the lamp turned up to the required brightness. Once they’d been lit, the mantles became extremely brittle, so a holiday ‘on the move’ required a stack of spares. Fitting a new mantle was a fiddly, time-consuming process – give me LEDs every time. In our embryonic camping days of the 60s, I remember the Tilley living on a specially fashioned hook suspended from the centre pole of the tent.

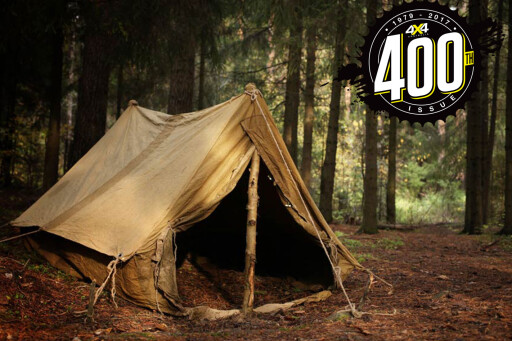

And what a tent it was! Ex-army, big enough to house the entire sixth division, the proper khaki colour, full canvas throughout, it weighed a tonne... or at least was heavy enough to warrant my old man fitting heavy duty, load-bearing rear springs to the family Holden. Putting the damn thing up was a full family affair, with a tween-age yours truly always sent to crawl in under the spread-out monster to locate and raise the centre pole.

Character-building, I suppose, or at least bicep-building. When it was raining, my brother and I were told not to touch the walls of the tent, which we did once of course, finding out that it makes the canvas leak. Polyester and treated canvas tents were a long way into the future, and, of course, there were no fly-screened, fully-mattressed swags at that time either. I guess a lot of that came from a difference in attitude. I don’t want this to seem like a preamble to a ‘living in shoebox in middle of road’ routine, but our expectations of outdoor life were vastly different.

Character-building, I suppose, or at least bicep-building. When it was raining, my brother and I were told not to touch the walls of the tent, which we did once of course, finding out that it makes the canvas leak. Polyester and treated canvas tents were a long way into the future, and, of course, there were no fly-screened, fully-mattressed swags at that time either. I guess a lot of that came from a difference in attitude. I don’t want this to seem like a preamble to a ‘living in shoebox in middle of road’ routine, but our expectations of outdoor life were vastly different.

In the late 70s me and a mate and his wife regularly canoed the Macquarie River, using the then completely bush camp area at Bruinbun as a base. While they and the recent family addition luxuriated in an André Jamet – then the absolute top end of tents, with a kitchen area, a change room for Bubs and so on, I tossed down a rectangle of foam rubber (uncovered) in the tray of the HJ45, chucking a sleeping bag of top of it. My pillow consisted of the sleeping-bag cover stuffed with my jeans, socks, a towel and anything else that fell to hand. If it rained, I pulled up the ute tarp.

I was lucky my wife Sharon had similar Spartan ideas. On all camping trips our ‘digs’ consisted of a groundsheet, two closed cell-foam mats and a doona; though we were seduced by self-inflating mats when they came on the market. We packed a two-person tent in case it rained, but the thought of airbeds, for example, never entered our heads. For my solo trips, I still have a very basic swag with a thin mattress but no flyscreening. If it rains, I pull the canvas flaps over my head; it’s as close to an old-fashioned drover’s swag as possible.

I heard the other day about a bloke who reckons he couldn’t go camping without solar panels and power packs, and realised just how totally foreign our ideas of roughing it had become to today’s breed of 4WD traveller. But it poses the question that if you need all the mod-cons you have at home, why waste money for a change of scenery? If that’s all you want, then hire a cabin on the beach. The idea of having power so you don’t miss out on the latest ep of My Kitchen Drools contrasts strongly with the practice of sitting around a campfire having a few Scotches and good conversation under the stars.

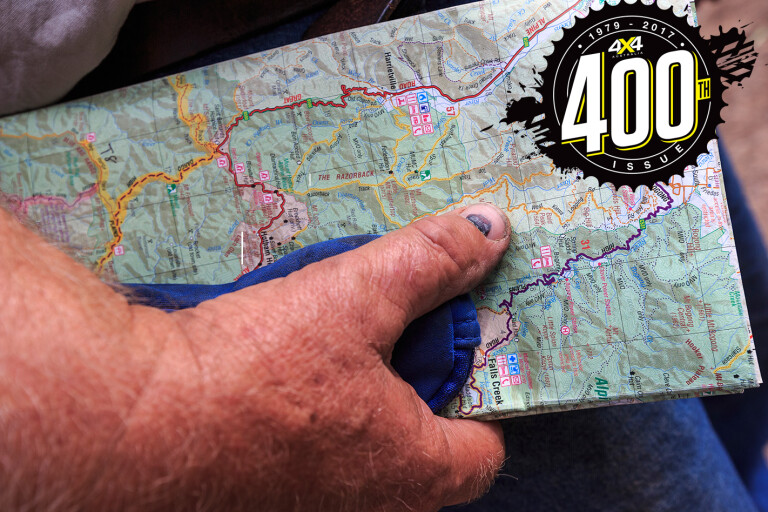

How else have things changed? Well, there’s little doubt that we had access to more places than are available now, and pay-as-you-go 4WD parks can now be found all over the country. And to return to the original topic, vehicles are totally different, with the skill levels necessary to pilot those early 4WDs now completely redundant as vehicles do all your thinking for you. In the old days, to tackle, say, a really rough rocky slope, you had to pick the right range (high or low), the right gear, the right line, and know just how much throttle pressure you’d need to avoid scrabbling and loss of traction.

Good four-wheel drivers could do it, crap drivers came to grief. Differences in vehicle capability off-road were marked, with Landies, Cruisers and Patrols being ‘first tier’, and others like Pajeros, with very little rear-wheel droop, definitely second tier.

Then along came traction control to blur not only those differing vehicle capabilities, but to act as the great equaliser for drivers (I’m not suggesting little gutter-jumper SUVs can now compete in the rough stuff with G-Wagens, so please don’t write in). I am saying that very mediocre drivers can now look like experts. And that’s a shame. Increasing reliance on electronics has also meant it’s impossible to work on vehicles to fix things when they go wrong.

Certainly, a good bush mechanic can rig up a replacement suspension spring to get to the nearest town, but if it’s engine failure you’re buggered. And in the middle of a desert, 50km to limp home just isn’t enough. So it’s been a voyage of mixed blessings. Didn’t mean to finish up negatively, but before you dismiss this as the ramblings of a grumpy old man, I was grumpy in my 20s. You wouldn’t have liked me then, either.

COMMENTS