US AUSSIES love things big: deserts, beaches, bananas and utes. It’s the reason Ford’s Ranger has been a runaway success from the older PJ and PK models.

Big styling, the largest engine in-class and a body that dwarfs almost all its peers; it’s also the reason WA native Ant first got behind the wheel of a first-gen PX1 Ranger. “They’ve got heaps of room inside,” he told us with an unmistakable West Australian drawl. “They’re an awesome car to drive; they perform off-road and have a strong driveline.” The only problem is, despite the 3.2 Duratorq motor being the largest in its class, it’s not exactly renowned for its reliability.

More 4x4 gear guides

“We started playing with the performance side of things,” Ant said. “Larger turbos, larger injector nozzles, tuning, etc., but being a PX1 they were quite dulled down on engine safety systems. I went through three motors, two turbos and a transmission.”

Where a normal punter might take the chance to slap a motor in it and jump ship to something else, Ant figured he’d double down and build one of the most bad-ass Rangers we’ve ever seen.

You see, despite Ant currently swinging the tiller on a Ranger, he’s actually built himself a cult following for his Duramax kits and conversions at Ozmax.

When your play toy is a Duramax GU, your wife’s runaround is a Duramax GU, and you suddenly find yourself with an engineless Ranger and a heap of Duramax engines looking for a home, it becomes pretty clear what needs to be done.

For those unfamiliar with the Duramax range of engines, they’re the holy grail of diesel V8s, with 6.6 litres (402 cubic inches) capacity, iron blocks, alloy heads, four valves a cylinder, and a whopping great turbo nestled in the V. The engines are built in Ohio with a joint venture between Chevrolet and Isuzu and power everything from Chevy Vans right through to huge medium-rigid trucks from GMC.

For those unfamiliar with the Duramax range of engines, they’re the holy grail of diesel V8s, with 6.6 litres (402 cubic inches) capacity, iron blocks, alloy heads, four valves a cylinder, and a whopping great turbo nestled in the V. The engines are built in Ohio with a joint venture between Chevrolet and Isuzu and power everything from Chevy Vans right through to huge medium-rigid trucks from GMC.

In their lowest standard tune they pushed out 250hp and 624Nm – just a hair under the twin-turbo LC200 – right up to 397hp and 1037Nm in later years. Put simply, it’s one of the biggest and baddest engines you can buy, and it’s purpose-built to haul anything you can put behind it.

Despite all that Ant reckons it’s almost perfect for converting into the comparatively pint-sized Ranger. “It was actually pretty straightforward,” he said. “They’re a common swap into Patrols, but this was actually a lot simpler.”

To kick things off Ant ditched the idea of mating the bent-eight to the Ranger’s box. It simply couldn’t cope with a more than a 100 per cent jump in torque. The old 3.2 came out, as did the factory six-speed and transfer; in their place went a huge six-speed automatic transmission from US-based Allison Transmission and a New Process NP263 transfer case.

To kick things off Ant ditched the idea of mating the bent-eight to the Ranger’s box. It simply couldn’t cope with a more than a 100 per cent jump in torque. The old 3.2 came out, as did the factory six-speed and transfer; in their place went a huge six-speed automatic transmission from US-based Allison Transmission and a New Process NP263 transfer case.

Due to the IFS arrangement, Ant was able to use the existing sump, helping to simplify the process. Then it was on to making it run.

“The communications system on the PX1 Ranger isn’t that smart,” he told us. “We wired the Duramax ECM in as a stand-alone unit then sent a few signals into the stock set-up so the speedo and tacho still work. As far as the stock electronics are concerned, there’s still a 3.2 under the bonnet.”

While the standard diffs are more than up to the task, Ant had a positive side effect swapping out to the new transfer case and control unit. "It now functions a little like full-time 4WD. If it senses slip between front and rear, it’ll kick itself into 4x4.”

While the standard diffs are more than up to the task, Ant had a positive side effect swapping out to the new transfer case and control unit. "It now functions a little like full-time 4WD. If it senses slip between front and rear, it’ll kick itself into 4x4.”

Ant explained that drive-in, drive-out conversions with all the parts supplied would roughly be a $30K job; although, he’s blown away with the results, averaging around 13.2L/100km around town and up to 17.2L/100km towing his 3400kg boat.

At twice the capacity of the stock 3.2L, the Duramax puts out an ungodly amount of power, too. Ant was able to run the Ranger up to 468rwhp and a mind-melting 1320Nm on a recent dyno-tune; that’s a 180 per cent gain in usable torque.

At twice the capacity of the stock 3.2L, the Duramax puts out an ungodly amount of power, too. Ant was able to run the Ranger up to 468rwhp and a mind-melting 1320Nm on a recent dyno-tune; that’s a 180 per cent gain in usable torque.

“You can’t even tell the boat is there,” Ant said with a laugh. “It’s 8.3 metres long. I lined up against a bloke in an LC200 with a tinny and blew the doors off him.”

The big concern of any engine conversion like this is weight distribution; throwing an extra few hundred kilos over the front axle can not only knock around springs and shocks, but drastically affect handling.

The big concern of any engine conversion like this is weight distribution; throwing an extra few hundred kilos over the front axle can not only knock around springs and shocks, but drastically affect handling.

“It actually only dropped 10mm on the standard springs,” Ant said. “The 3.2-litre and six-speed is a heavy combination, and the NP263 transfer case is magnesium which keeps weight down with the conversion.”

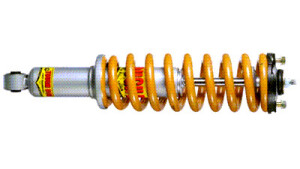

With goals of a pre-runner-inspired build, Ant figured the Ranger could do with a tickle underneath. It’s running heavy-duty XGS two-inch-lifted springs up front to deal with the slight weight increase over stock, and they’re wrapped around Ironman Foam Cell Pro shock absorbers. The rear has a matching combination; although, there’s a 50mm body lift, bringing the overall ride height up and allowing Ant to slot the big Allison automatic in the transmission tunnel without any body modifications. A set of Total Chaos upper control arms were also given the nod to get the alignment back into spec.

With goals of a pre-runner-inspired build, Ant figured the Ranger could do with a tickle underneath. It’s running heavy-duty XGS two-inch-lifted springs up front to deal with the slight weight increase over stock, and they’re wrapped around Ironman Foam Cell Pro shock absorbers. The rear has a matching combination; although, there’s a 50mm body lift, bringing the overall ride height up and allowing Ant to slot the big Allison automatic in the transmission tunnel without any body modifications. A set of Total Chaos upper control arms were also given the nod to get the alignment back into spec.

As Ant built the Ranger to be more of a pre runner-cum-tow tug, the heavy-duty barwork is left to the twin Patrols in the garage. Instead, the PX1 is sporting a clean de-badged look with a bunch of colour-coding, a huge four-inch snorkel, stock barwork front and rear, and 35-inch tyres in the guards.

Ant’s rubber of choice is the ever-popular Nitto Terra Grappler, which gives the perfect combination of soft sidewalls for beach work and longevity. He’s wrapped them around 16-inch Brutes from Allied Wheels.

Ant’s rubber of choice is the ever-popular Nitto Terra Grappler, which gives the perfect combination of soft sidewalls for beach work and longevity. He’s wrapped them around 16-inch Brutes from Allied Wheels.

On the inside are a handful of off-road modifications; although, with the Duramax Ranger set up for touring, Ant’s opted for the bare necessities for beach fishing runs with mates. There’s an Aeroklas canopy covering the rear end, while a brake controller teams up with sat-nav inside. Hidden inside the glovebox is a UHF, while the aerial is also hidden to finish off the clean look.

There are plenty of people who’d throw the catalogue at a 4x4 before being happy, but Ant’s a prime example of a new breed of off-roaders. A purpose-built rig for getting out there and doing the job, a bunch of style thrown into the mix, and a driveline that puts a grin on Ant’s face from ear to ear every time he stomps on the loud pedal.

There are plenty of people who’d throw the catalogue at a 4x4 before being happy, but Ant’s a prime example of a new breed of off-roaders. A purpose-built rig for getting out there and doing the job, a bunch of style thrown into the mix, and a driveline that puts a grin on Ant’s face from ear to ear every time he stomps on the loud pedal.

Bee-cee-what now?

In years gone past, the hardest part about an engine conversion was physically fitting it in. In some circumstances you’d need an adaptor, which added expense and an extra step but wasn’t an insurmountable problem.

When engines became electronically controlled things got a little more complicated and required extensive wiring, but they could essentially be standalone units – yank out the existing engine wiring and ECU (engine control unit) and put the new stuff in.

Things are now a little more challenging. The original offender was electronically controlled transmissions running their own ECU and needing to communicate with the engine’s ECU. In short, some transmissions simply couldn’t be paired with some engines, even if you could physically connect them.

Things are now a little more challenging. The original offender was electronically controlled transmissions running their own ECU and needing to communicate with the engine’s ECU. In short, some transmissions simply couldn’t be paired with some engines, even if you could physically connect them.

To make things even more complicated, most current-generation 4x4s run what’s known as a BCM, or Body Control Module. They’re essentially an ECU that controls anything that needs controlling. Headlights, air-con, windows… even shifting the transfer case from high to low range. Conversions into modern 4x4s need to not only power themselves but trick the stock setup into working as well. It’s the main reason modern engine conversions are getting harder and harder.

COMMENTS