In the late 1950s and early 1960s nobody in Australia had any idea how you organised and ran a drag race meeting, so somebody had to think it up. That guy was Max De Jersey. He also edited the second-ever drag racing-cum-hot rodding magazine in Australia, was the first person to make his living from the sport in this country, the first drag racing promoter, a founder and the first secretary manager of the Victorian Hot Rod Association (VHRA), the first sanctioning body for drag racing and hot rodding, and assisted in the founding of drag racing in Queensland, New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria, as well as a racer of note in his day. And all this was before the age of 26!

First published in Street Machine’s Hot Rod 15 magazine, March 2015

When De Jersey was a young kid who’d just earned his driver’s licence, a mate invited him to attend a meeting of the Southern Hot Rod Club (SHRC). By 1959 he was on the organising committee of the first drag race at the Pakenham strip, outside Melbourne, which was being run by the club. The event was run under a CAMS sanction, but the CAMS steward never showed up, so after waiting hours for him they ran the event anyway.

De Jersey had to go to a CAMS State Council meeting to give a report on the race but when he explained what had happened and was reprimanded by the CAMS people, the SHRC decided to skip any future involvement with the circuit racing body. Instead, the club negotiated public risk insurance direct through the same company CAMS was buying it from – and got it at a cheaper rate.

After drag racing at Pakenham stopped in 1961, hot rodder Graham ‘Bluey’ Wilson pointed out a fabulous strip of essentially unused asphalt at the old Commonwealth Aircraft Factory, at Fishermans Bend, just two kilometres from the GPO. The drag racers managed to gain access to the strip with the help of the Victorian Police Motorsports Club. Again, De Jersey was on the organising committee.

The first event at the newly renamed Riverside strip attracted only about 30 spectators, but the second race revealed a huge crowd waiting to attend, with a bemused gate official charging 50 cents a head to enter. Soon the committee was dealing in big money and in recognition of the large number of other hot rod clubs then in place in Victoria, they offered De Jersey the job as track manager and promoter, as well as the position of secretary of the newly founded VHRA at £20 per week.

In late ’62 De Jersey began an eight-page journal — duplicated on a Roneograph — intended as a program for each Riverside meeting. After a while photographer Len Shaw suggested they get it printed so from July 1963 Australian Dragster Monthly began appearing as a printed and bound magazine of 16 pages. De Jersey wrote and assisted in its layout and production.

In June 1964, after the First National Auto Show hot rod exhibition at Balgowlah in Sydney, De Jersey was one of 10 from the hot rodding scene in Victoria and NSW who signed a handwritten one-page document agreeing to form the Australian Hot Rod Federation to nationally “promote, regulate and control the sport of hot rodding in Australia”.

Track preparation was an unknown art in 1966, as was the notion of stopping racing when it rained. Promoters expected competitors to keep going even in inclement weather

In addition, the experienced VHRA assisted in training and setting up the drag racing at Castlereagh, near Sydney, which held regular monthly meetings from 1965. Then they went up to Queensland for the new Surfers Paradise strip in April 1966, as well as helping create the eighth-mile Two Wells track north of Adelaide, and assisting the Bairnsdale Car Club run drag racing events at Bairnsdale airfield from 1964. De Jersey was in the forefront of all of these ventures and was being paid by Surfers Paradise strip builder Keith Williams to travel to the Gold Coast to advise on construction of his new track.

In 1966 he became heavily involved with the organisation and running of the Dragfest tour by six American dragsters and spent nearly two months on the road making that happen. When the event was forced to move from the Riverside track, it was De Jersey who rang Calder Park and got drag racing to happen there for the first time.

As if that wasn’t enough, he was also a racer. He ran his father’s brand new FC panel van at the first Pakenham meeting in 1959 (Dad only found out years later) and continued running other street cars there and at Riverside.

“I had nothing to do with the running of race meetings,” De Jersey explains. “We had a full crew of people who ran the meetings. If there was a problem, see me on Monday – I raced on Sunday.”

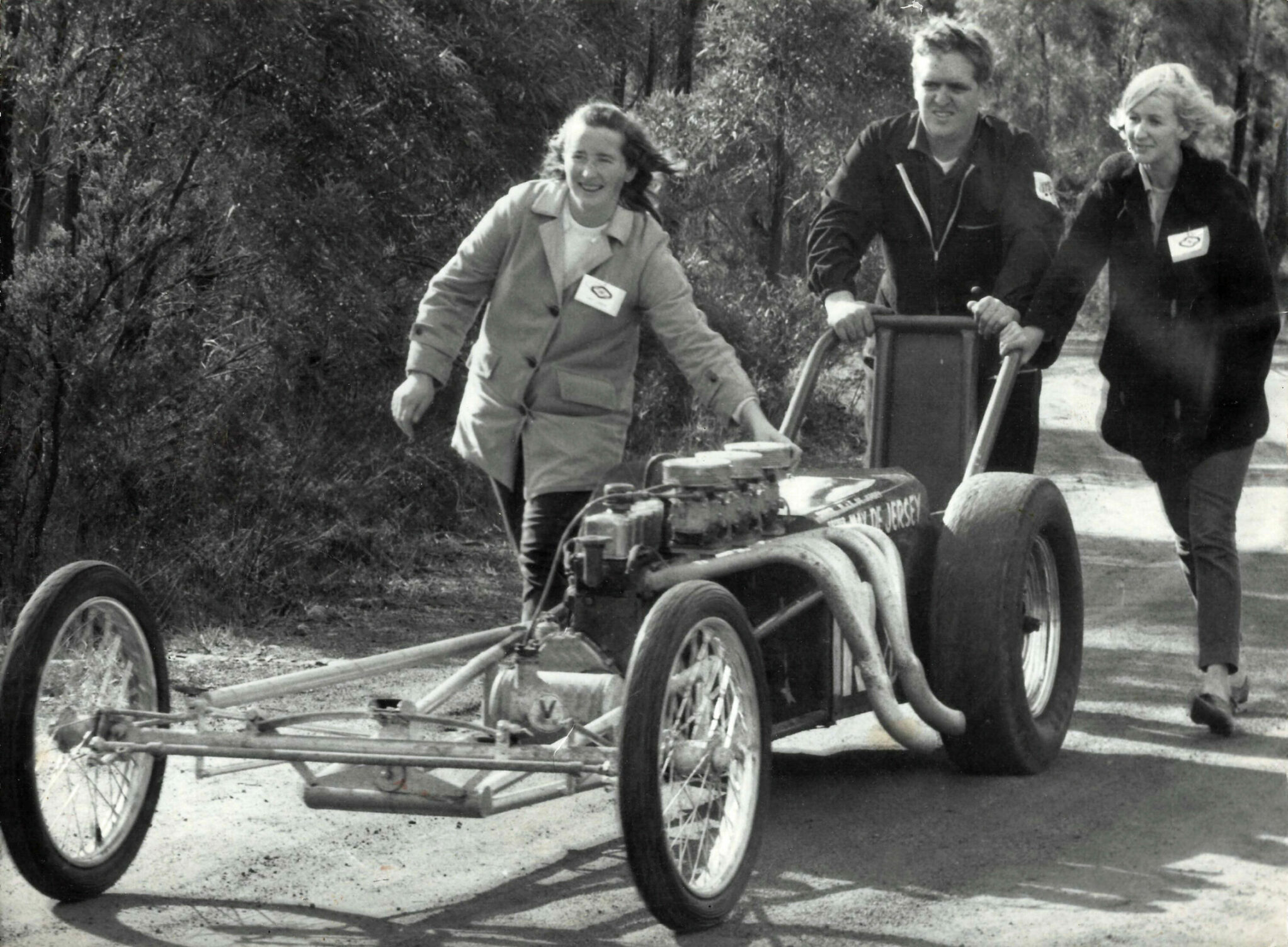

His first attempt was with a Holden six-powered ‘space frame’, which he was testing on a country road when he discovered a cow in his path as he came over a rise. The space frame was a write-off, and so was the cow, for which he had to pay compensation to the farmer. There was a nice line in a magazine of the time about “De Jersey shunting de Jersey”.

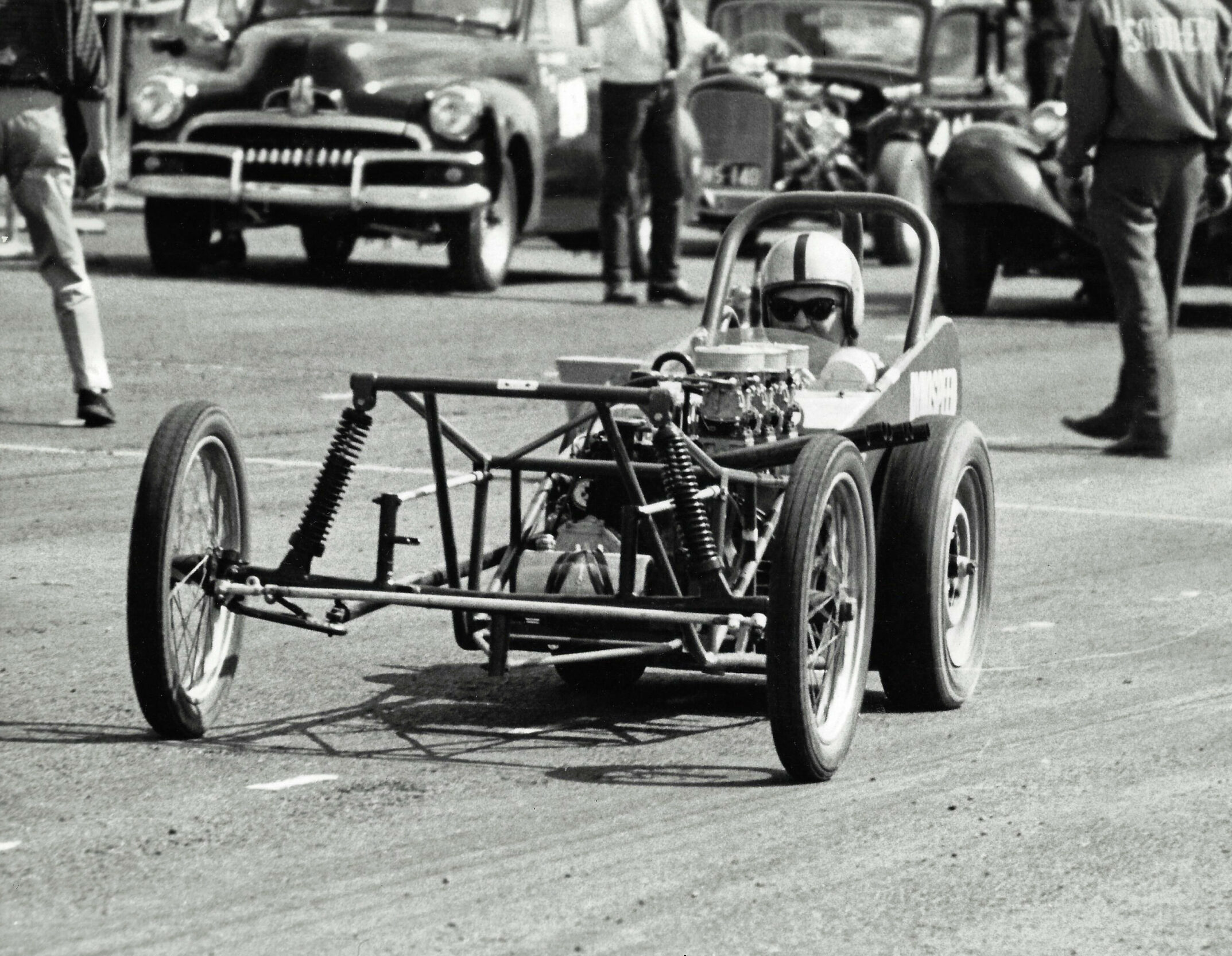

Around 1960 he ran a ’34 sedan at a couple of Pakenham meetings, then came an FX, a drive in a Perfectune Holden followed by a Holden six dragster in 1963. In 1964 he bought the Norm Wilson dragster, thought to be the first Holden-six FED. He only ran this strange spidery car for a brief period before building a new Holden-powered dragster. In late 1965 he built a 179-powered FJ panel van, which he tagged ‘Elizabeth’s Grocery Getter’, after his wife of the time. That car only lasted until the following April when it was lost in a towing accident while on the way to a race in Sydney.

In 1966 De Jersey moved away from Victoria after the Riverside track closed, to Queensland where he drove Bill Birmingham’s ex-Norm Beechey dragster for a while and later punted other vehicles on occasion, but soon became firmly lost in the world of speedway.

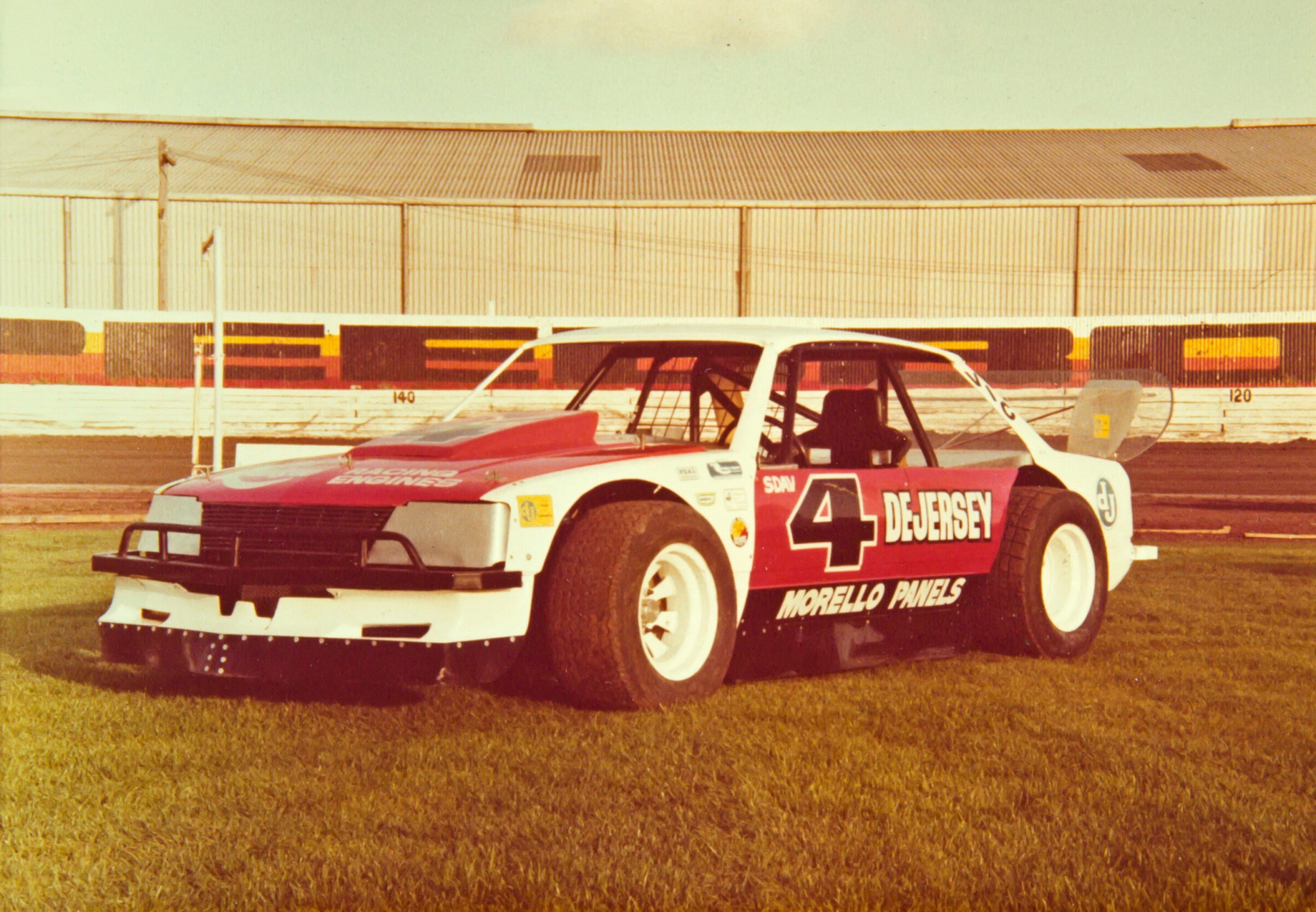

With a unique résumé that includes all kinds of dirt track cars, AUSCARS, Group E, Group A touring cars and sports sedans, Max has raced just about everything bar open wheelers. An engineer by trade, he has also built damn-near every kind of race car too. We visited Max at his Kingaroy home last year, and heard some very cool yarns. Here are just a few:

FIRST CIRCUIT CAR

Max De Jersey’s first foray into the world of motorsport was at just 14, when he built a TQ speedway ride, thought it never saw action thanks to parental disapproval. Upon getting his driving licence, he started work on an FX Holden, which he set up with a four-speed ENV gearbox, with his father’s help. “The family business was in bakeries, so we got an old cast-iron plate that was used for baking crumpets and machined it down to make the bellhousing adaptor,” Max says. The engine had a 1/8th overbore, a hot cam, triple Strombergs and was tuned by Jack Wilson.

“I bought a set of Dunlop RS4 tyres — it cost me a week’s wages for each,” he says. “In ’59/’60 they were the best tyre to race on.” The FX was intended to be a street-registered circuit car, so Max dutifully presented it to get it inspected at the rego branch, which at that time was located in the Exhibition Buildings in Carlton. “The cop comes out, looks at the car and asks: ‘What the fuck is this? No interior? Built it yourself, did you?’” Then he sees the camber on the front wheels and says: ‘You’ll have do something about that front end, it’s worn out.’

I told him that it was set up for negative camber and it was all brand-new, but he wouldn’t have it. Then I fired it up for him and it had so much overlap on the cam that the banging coming out of the Strombergs was louder than the exhaust. So he knocked me back, and I raced home, pulled the carbies and exhaust off it and bolted the stock stuff back on it.

I adjusted the front so that the wheels would sit up straight, took it back to the cop and he gave me my plates. Then I put everything back on the same day and went out for a test drive. Of course, I get pulled over and the cop asks the same question: ‘What the fuck is this?’ I show him the paperwork and he goes off his brain ‘You got this registered today? What hope have we got if they register shit like this?’

“Dad and I took it out to Phillip Island on a private hire day and I’m racing around in this thing. A couple of guys come up and tell me I’m running near the Appendix K record and ask if I’m coming to the race meeting next week. I was only 18, but Dad wouldn’t sign the forms to allow me to race, so I sold the car on the Monday in a fit of temper. The guy who bought it came third in the race that weekend!”

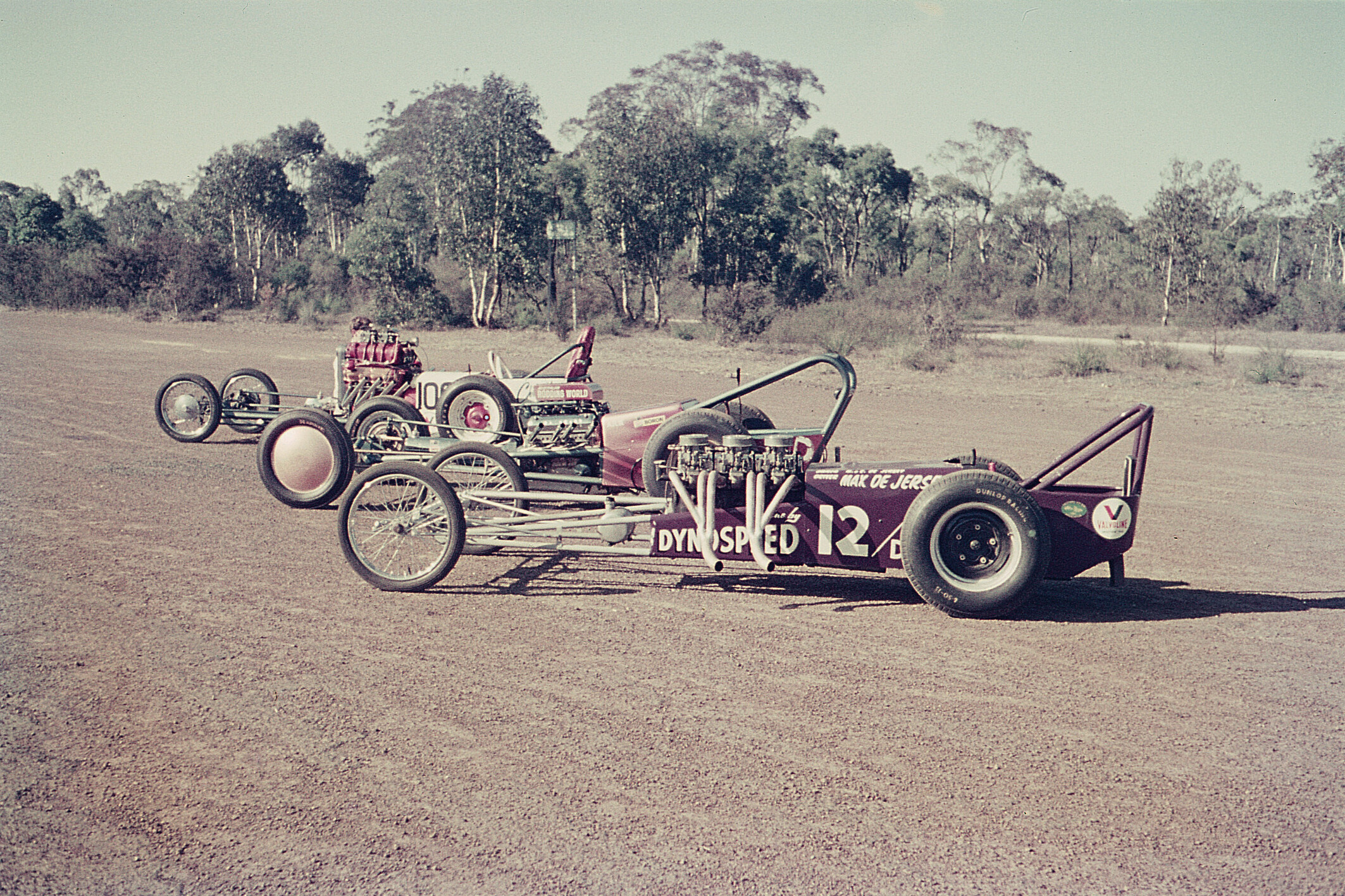

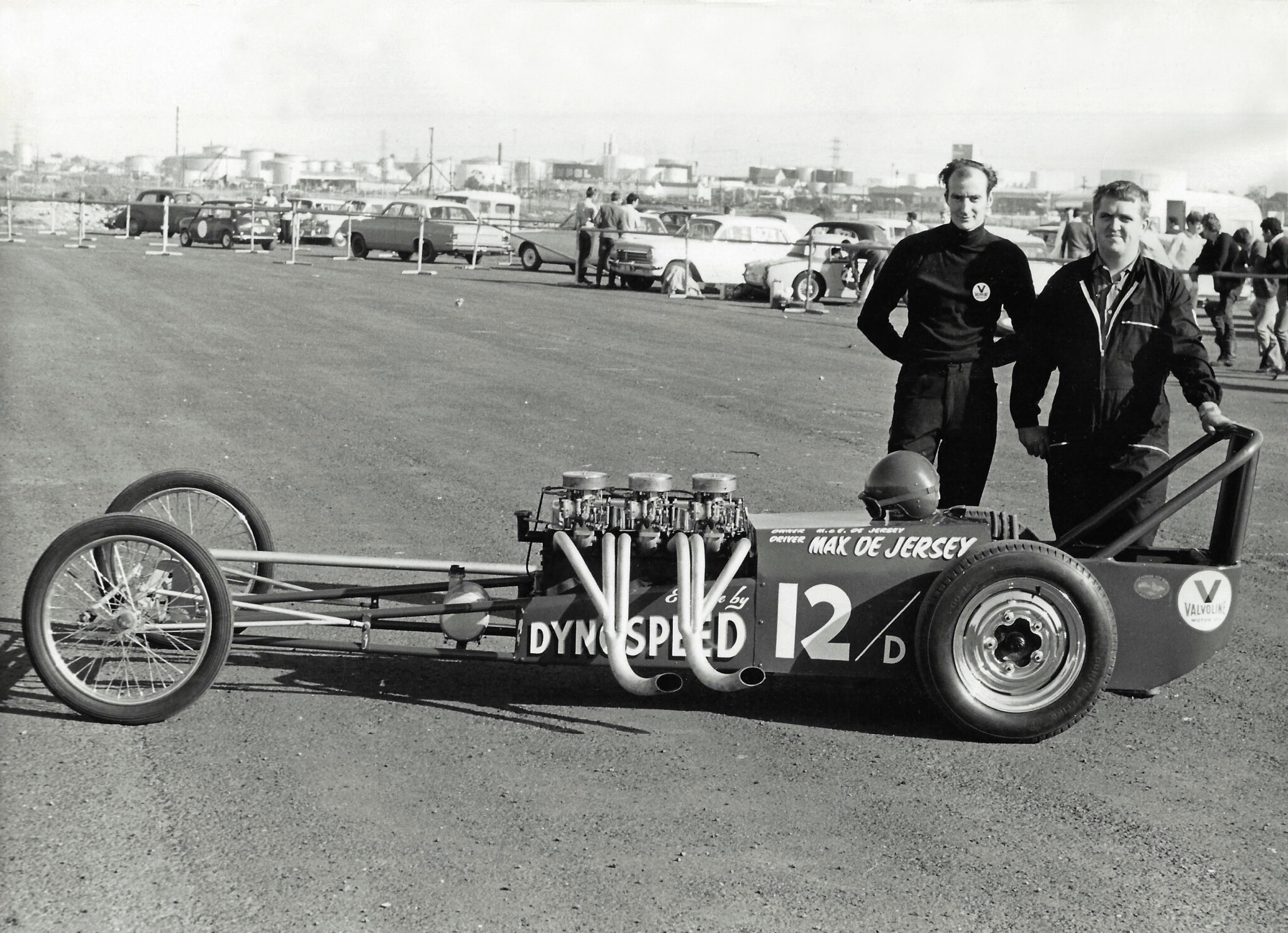

THE DYNOSPEED RAIL

“When I was doing Australian Dragster Monthly, I used to travel around selling the advertising. John Auld at Dynospeed was a circuit guy, but he was intrigued by drag racing. He asked me about my dragster.

It had a grey motor with SUs and ran 12.6s at 100mph. “He asked me how I thought it would go with a new 179 red motor? They were just brand-new at the time, you could only buy them with the auto transmission, but he said he could put his hand on one.

I said ‘Done, we’ll call it the Dynospeed rail.’ I came back in a couple of days and there was a brand new 179 sitting there in a crate. The only problem was that there was no hot-up gear for them yet, so John said I should go and see Eddie Thomas. He ground me a cam and modified some elbows so we could fit three dual-choke Mikunis.

Eddie reckoned they’d be perfect in a dragster. I massaged the head, then put it all together. We dynoed it at Jack Wilson’s place and had well over 200hp out of it.” The rail ran a best of 12.1 at 113.9mph, before it was soon sold as a roller to Graham Rose, who couldn’t wait out the time Max quoted him to build one from scratch.

THE GROCERY GETTER

“The FJ van, that’s a story,” Max says. “At the time, the VHRA had a ’46 Chev panel van that they’d bought el-cheapo. We had a lot of stuff to cart around, including home-made timing gear. We did a bit of work on it, but it was pretty bad and thirsty. By this time, we’d formed the AHRF, so I’m travelling to Adelaide, Surfers, Tasmania, racing around everywhere. So I bought the FJ van for myself, painted it red and got Australian Dragster Monthly painted on the side.

As the bank balance improved, we decided to upgrade to Chrondek timing gear and then bought a brand new EH Holden wagon to cart it around in. So what to do with the FJ van? I had sold my dragster to Graham Rose, but I still had the Dynospeed motor, so we combined the two. I pulled out the grey and my mate Cliff McIvor suggested we cut the firewall out and move the engine back.

So we gas-axed it, put a bucket seat in it, turned the gearshift around and kept cutting until I could reach the lever. We boxed in the hole and then we had all this room at the front, so we ditched the factory crossmember and went to the local trailer joint for some leaf springs and some tube. We put FC stubs and brakes onto the tube front end and we were away. The steering was diabolical!

Then I heard about some 4.875:1 diff gears that a taxi mob was using for their four-cylinder diesel conversions into FC Holdens – I thought: ‘I gotta have that!’ Then I needed some bigger rubber. I asked Norm Beechey and he gave me a couple of 15in Blue Streaks off his Mustang. That all took about three weeks, so when it was done, I took the rubber pad off the clutch pedal and took it out into the street. The idea was to rev the ring out of it, slip your foot off the clutch and it would jump the front wheels!

But it ran out of puff in about 10ft, so Cliff came up with the idea of filling the tailgate with lead. We drilled some holes and sat there dripping lead into it. It weighed about 180lb, it took two of us to pick it up. But pull wheelies? You’ve never seen anything like it.” The car snapped both axles on its first test-run at Calder and was destroyed in a towing accident before it could make a representative run.

RACING FOR FUN & PROFIT

“When we moved to Queensland, one of the things I did for work was odd-jobs for Keith Williams, who owned Surfers Paradise Raceway. One time he asked me to drive down to Sydney to pick a car up from the docks for him and when they cracked it open, it was a 250LM Ferrari that had been refurbished by the factory and was ready for the 1966 Rothmans 12-hour at Surfers! I ended up helping Jackie Epstein and Paul Hawkins with the car for the race.

The next year, I wanted to get in on it myself, so I did some research and found out what the least populous class would be – Sports Racing, over 2.0-litre. It only had two other cars in the class, a Lola and a Ferrari. So I bought an FJ and started putting something together. Repco supplied me pistons, extractors and a cam, another mob supplied me some Olympic GT Radials and a boat place gave me some fibreglass guards and a bonnet.

I put in a bigger radiator and fitted some Customline rims with FJ centres. To be designated a finisher, you had to do 70 per cent of the winner’s distance. I looked at last year’s times, figured the winner would be 10 per cent quicker and worked out that I could make it if I did 358 laps doing 1.52s. I went out for a test and found the FJ would do 1.49s in top gear the whole way ’round and I only had to tap the brakes twice!

I had organised a mate to co-drive, but he disappeared and they wouldn’t let me scrutineer without a co-driver! I was wandering around the pits like a lost sheep, then I bumped into Bill Shaw. His son was there, didn’t have a drive and had a full FIA licence. This kid was used to racing Brabhams and he came over, stood in front of the FJ and asked where the race car was. I said: ‘You’re standing right in front of it!’

The disappointment! I explained all he needed to do was do a two-hour session and I’d be as happy as Larry. He qualified, said it was like watching grass grow – until the Ferraris came fanging past. So race day comes, he does his two hours, we change a tyre and get black flagged for a dodgy tail-light, but apart from that, it runs like a dream.

With half an hour to go, the temperature starts going up. I come in and the gauge goes off the dial. We stuck half a dozen jars of Bars Leak into it, make it back out and do just enough laps so that we finish third in our class. I spent $538 on the whole thing – including purchasing the car – and won $750. The only time I made money out of racing!”

SPEEDWAY

After the 12-hour, someone told me about stock car racing that was happening at Rudd’s Paddock at the back of Surfers. Some old farmer had made a track with four straights and four corners. I thought I’d have a go and knocked the glass out of the FJ and built a rollcage out of waterpipe! I fronted up to the meeting on the same set of GT radials.

I started at the rear of the field, got to the front, then clipped a telegraph pole and rolled it. But that was it for me, I was hooked and got into speedway big time, I built over 50 cars. I built a near-new HR Holden for a guy called Ron Grose and he then introduced me to a bloke called Dave Taylor, who had a business called Vogue Homes.

Straight up, he asks me if money was no object, could you win every race? I told him, not quite, there is a little thing called luck involved, no matter how good the car and driver are. Then he asked: ‘What car would you build?’ I said a Mini, as they were the car of the future. He said: ‘How much would it cost?’ And I say: ‘How long is a piece of string?’ He said: ‘Put your hand out,’ dropped a thousand dollars in my hand and said: ‘Now you drive for me, I own you.’

While perhaps best-known on the dirt tracks for his exploits in Minis, Max tried his hand at plenty of others, including this Fairlane Super Stocker, which he converted to left-hand drive

That was one of the best times of my life – what a deal! The next day I went and bought a Morris 850, then I went to the wreckers and bought a Morris 1100 S motor. I built the car in two weeks and at the first meeting I ran second in the first heat, first in the second and won the feature. That was $1000 prize money.

The deal was, Dave bankrolled the building of the cars, I covered the consumables and we went halves on the prize money. The next meeting I rolled seven times, dinted the roof on Allan Butcher’s Monaro and destroyed it. On Monday, Dave rings me up, asks me if I’m okay, and says: ‘Not to worry, I’ve bought another car already’. The first year, I won $17,300.”

Comments