Back in the days when men were men and FJs were all the go on the quarter-mile, two young guys from southern Sydney carved a name for themselves with a devil-may-care attitude and an inventiveness that left others in their wake.

First published in Street Machine’s Hot Rod 11 magazine, June 2013

Ron and Alan Moore (the latter better known to his mates as “Wally”) were car-mad young blokes who, in 1966, ventured west to the then new Castlereagh Dragway to take a squiz at this new motorsport that had just sprung up near home. Wally had a mate, another youngster by the name of Warren Armour, who was running, and they went to watch him race. The brothers took one look and a month later were back, this time with Ron’s early model Morry Minor with MG power to give it a shot.

“It had a hot cam, twin carbs and extractors and whatever you could do to it,” says Ron, who was then aged 19. “I forget what speed it did but after a while it ended up doing 17.6 seconds, which wasn’t too bad for those days.”

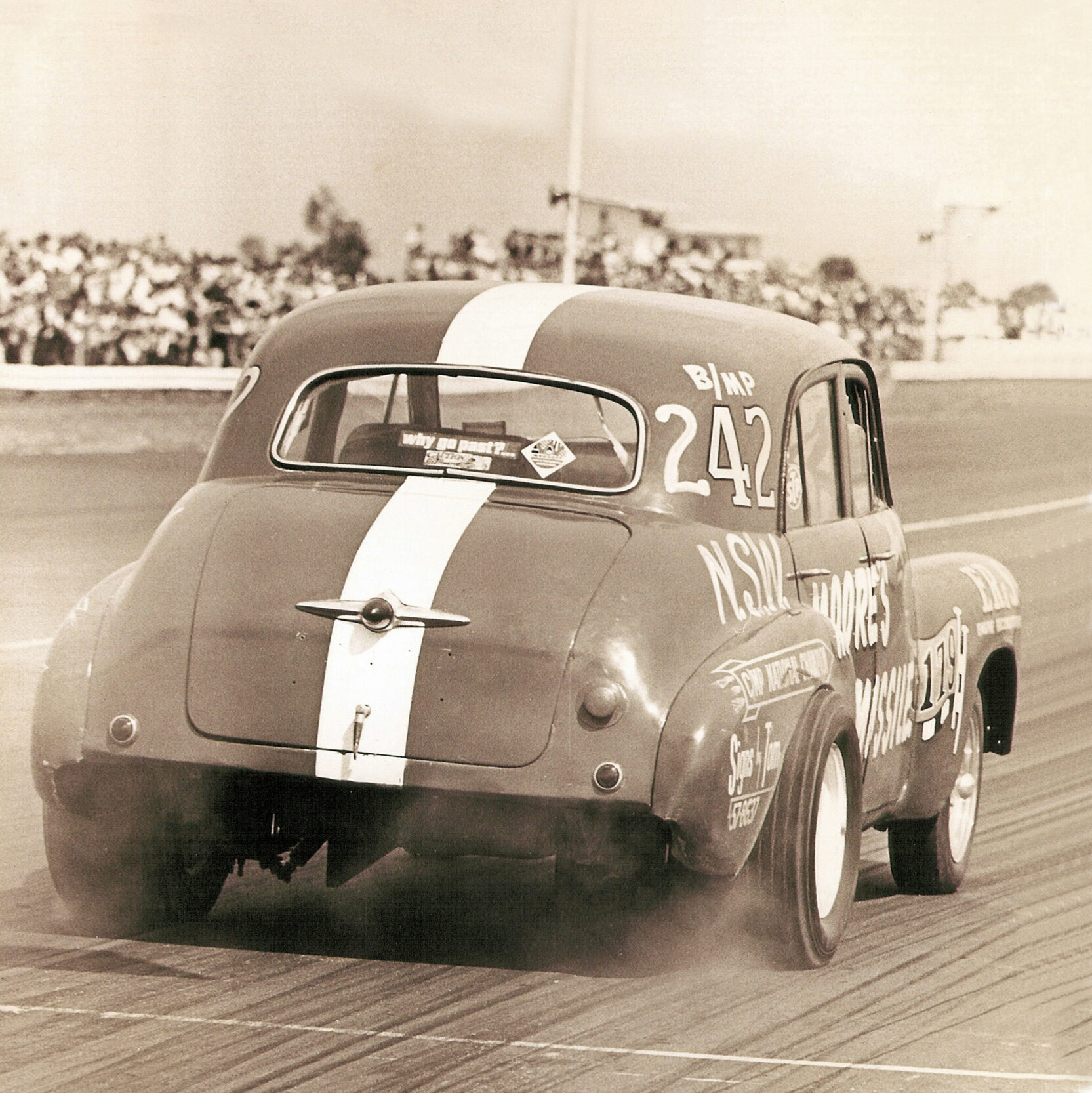

After that, the Moore boys ran their street cars – both had hot EHs – until around 1967, when, sick of beating their daily drivers to death, they decided to build a race-only vehicle. That fully signwritten FJ, dubbed Moore’s Missile, hit the strips in September ’67 with the engine out of Wally’s EH. “We modelled the car on a green ute run by a guy named John Price,” recalls Wally. “He’d repowered it with a 186, and that gave us the idea that this was the way to go. The FJ was cheap, it was lighter, readily available, and you were game to do anything to it rather than go cutting up a good late-model vehicle.

The motor was a tough streeter – triple 1-3/4in SUs, head, cam, extractors, stroker crank. At its first meeting, the car had a quarter of a second on all the opposition and forced its way into the final against old mate, and, by then, hot shot Warren Armour. Ron, who was driving, blew it on a red light. “We got Merv Waggott on board and he gave us the ground work on where to go with it,” recalls Wally. “He was as smart as, and built engines for Formula Ford and such things. He gave us a lot of help, and for free, so we were happy to keep him on board.”

“He seemed to be happy about it,” Ron continues. “He kept throwing camshafts to us whenever he had a new design. As time went on we were rather experimental in what we wanted to do, because we weren’t really risking anything. We’d go over with these weird ideas and Merv’d try to make them work.

“Understand, we were just sort of making this up as we went along. Alan would put forward an idea and I’d say, ‘Oh, yeah,’ or ‘Nah,’ and I’d throw ideas at him.”

“Like once, we cut all the counterweights off the crankshaft,” says Wally. “I asked Merv, ‘Why do we want all these on the crankshaft,’ and he said, ‘Well, the lighter the better,’ so we cut ’em all off. Merv didn’t think it’d run, but it went like a rocket.

“We had a big, big-bore engine that was so thin it used to leak water into the oil, so we tried transmission fluid as our coolant because we figured if it leaked in it wouldn’t matter, and it should last at least a quarter of a mile… But that didn’t work.”

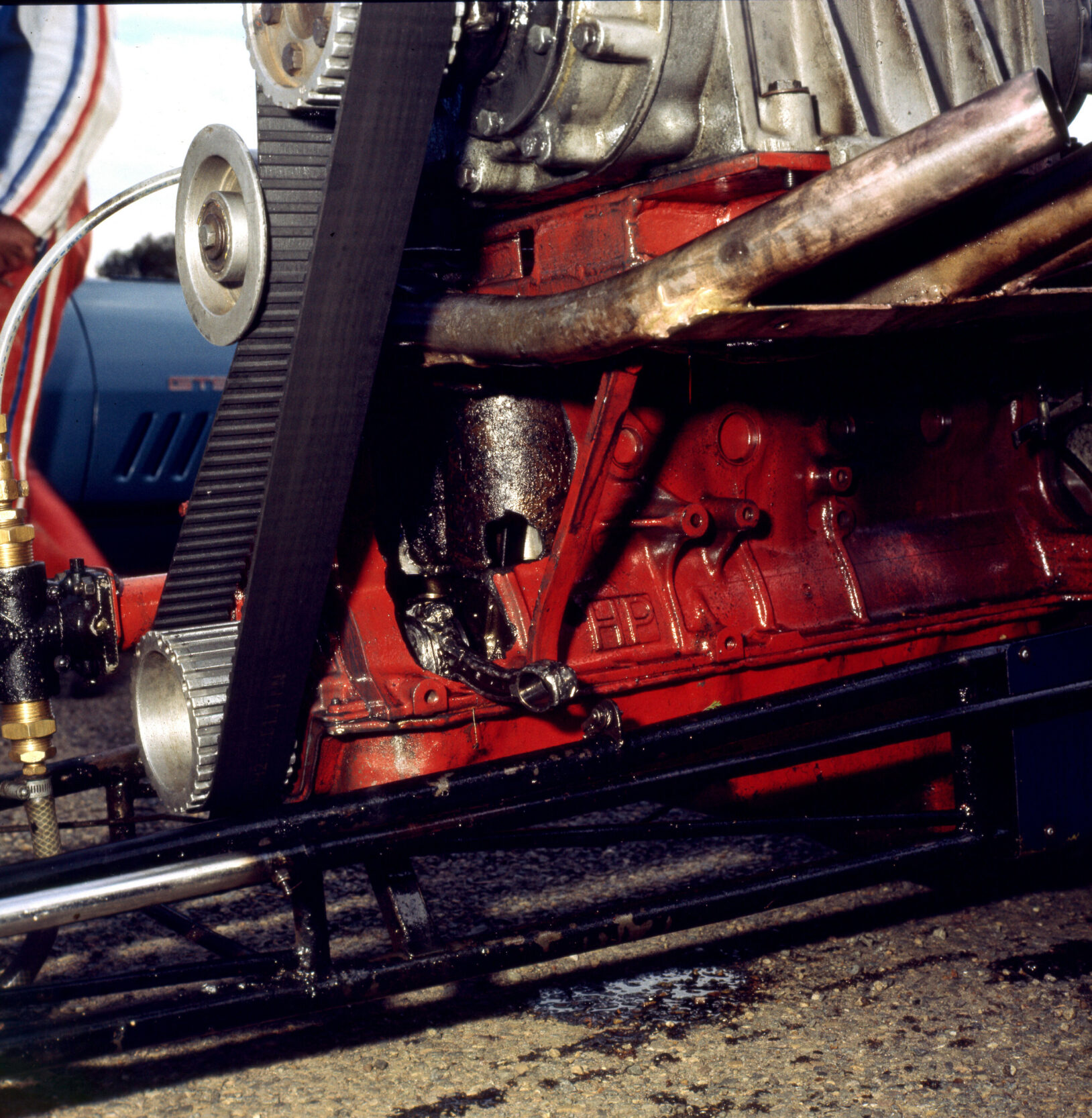

“We had one block that we bored all the cylinders out of,” says Ron, “And we welded in sleeves with a steel plate at the top dowelled down each side to stop it spreading – this was all Alan’s work, because that’s the sort of business he’s in. Then we bored them and put sleeves inside, because the first sleeves were cracked after we’d welded them. It had a 3-7/8in bore, which was about a quarter of an inch up on a 186. So with a 3/4in stroker crank it gave us about 240 cubes.”

“The car ran, but we couldn’t seal it,” Wally explains, “And so we couldn’t keep it cool.”

“It’s hard to recall all the details of this, because we had all sorts of stroker cranks over the years,” adds Ron. “We used to sit down in the shed with a stick welder and start building up the journals on one side and then Alan’d machine them to size later.

“We had no secrets, though a lot of people didn’t believe it when you told them”

“We had a 1/4in stroker at our first race with the FJ. Warren Armour guessed we had a stroker because we were outrunning him by a couple of tenths, and, since we had a Repco sticker on the back of the car, he was convinced that’s where we’d got it. He was at Repco on Monday morning asking after one for himself!”

The guys also tried a four-speed box from a Humber, thinking it would be nice and strong, but it was heavier, and, using only second, third and top cost them a half a second. Back to the drawing board.

The rear was the Holden leaf springs with a big pair of traction bars welded to the diff, with an air bag on the driver’s side to keep it level. The front end had two sets of springs welded together, one on top of the other, to lift it up.

The rear tyres were old Goodyear road-racing rubber from Formula 5000s, about 12in wide. These were the days when slicks were scarce indeed, and mostly guys ran street tyres with a slick recap.

The brothers put much of their success down to running a Holden diff housing, while everyone else was going for the heavier duty items such as 9in Fords. Not that that original FE banjo housed Holden gears, as the Moores had managed to squeeze in a set of Toyota gears, which “didn’t exactly fit”, but they worked, and that gave them a 4.4:1 final ratio. This was way ahead of the 3.89 ratios available to everyone else, and, combined with the old Holden three-speed gearbox, grabbed them a bunch of time off the line every time.

“Whatever we found worked, we used to tell people about,” Wally says. “We had no secrets, though a lot of people didn’t believe it when you told them.”

“Except when we first started,” Ron chimes in, “When Warren Armour came over and asked, ‘Are you running a stroker?’ The answer was simple: ‘No!’”

“We ran whatever we had, or what we could find at the cheapest price, or make ourselves”

“In those days, as you came back up the return road you were simply paired with the next guy in line who was a winner; there was none of this ladder system like they have today,” Wally continues. “If we qualified top we’d go out and the rest of the field would stay back in the pits because nobody wanted to be next out because they’d be the ones who’d have to race us. We had times when coming back up the return road we’d have guys pull up and ask us to overtake them because they’d say they couldn’t beat the next guy in line and they wanted to go another round.”

“We ran very much on a budget,” Ron says, “And so we ran whatever we had, or what we could find at the cheapest price, or make ourselves. We just wanted to race, and we were there no matter what. If we didn’t have what we wanted, we’d simply say well, what have we got?”

These were the days when the guys simply didn’t miss a meeting.

“We used to pirate bits from wherever we could,” Ron confesses. “I remember my road car at one time had a block with a patch and a ring compressor key welded into the side of it. After we’d put some rods out in a race, we swapped blocks with the road car to go racing the next meeting. One time we took the motor out of our dad’s EH to pinch the block, which he wasn’t too impressed about, but we promised him a new block out of the money we were going to win. A Holden block and piston set were pretty cheap in those days.”

There’s an often-told story of the guys rushing between rounds to rebuild the diff, and someone dropped the crown wheel in the sand. Everyone stopped talking and looked on, convinced that this was the end for this meeting. One of the boys simply picked it up, wiped the big lumps off with a rag and started putting it back in, explaining that it only had to go a quarter of a mile, so she’d be right.

“I’ve often heard variations of that tale,” Ron says, “and basically, it’s true. If you were between rounds then you didn’t get a choice, and we wanted to race, and win – not that that always happened. Sometimes that gap between rounds might have been as little as 20 minutes, and we would do almost anything to get our car back out there. Often our wins were more bluff than reality, as we’d go out for the final knowing the car didn’t have a hundred metres in it but we put on a front that we were there to race and the other guy’d red light.”

That first FJ had a pretty rough body, with rust and dents where you didn’t want them. While towing it home to Hurstville, there was some trouble and a wheel came off part way. It was later replaced by a much better body. The boys even tried a third car, specially built for one of the Mr Holden titles, but it didn’t work out the way they’d hoped, so they got rid of it and went back to car number two.

Despite being rough, that first FJ was to take them to their only Nationals win in 1968 at Calder. That event was to have greater repercussions than simply adding a neat trophy to the mantelpiece, as there was a young Melbourne racer there running an EH. His name was Ron Harrop, and he was frustrated that he couldn’t get anywhere near the times these highly-rated Sydney drivers were producing. At the end of racing, he walked over to the Moores and asked what their secret was. They took one look at what he was running and advised him to put his running gear in an FJ, and the rest of that story is history.

“We used to tow the FJ around on an A-frame in the early days,” Ron recalls. “One night going up to Castlereagh we were pulled over by a copper. We used to tow it on an interim label, and we used to just alter the interim label so that it would fit another date. The cop took one look and said, ‘If I see you two towing this thing back again, you’ve had it.’ We didn’t know him at the time, but Jim Kerr was at the track with his tow truck, so we booked him to tow the car home to Hurstville.”

The guys dabbled with other cars, winning the Senior Division at the Mr Holden titles in 1968 in Ron’s street EH, and later with a Torana XU-1 supplied by a sponsor in 1971, but it was way too slow, so they gave it the shove.

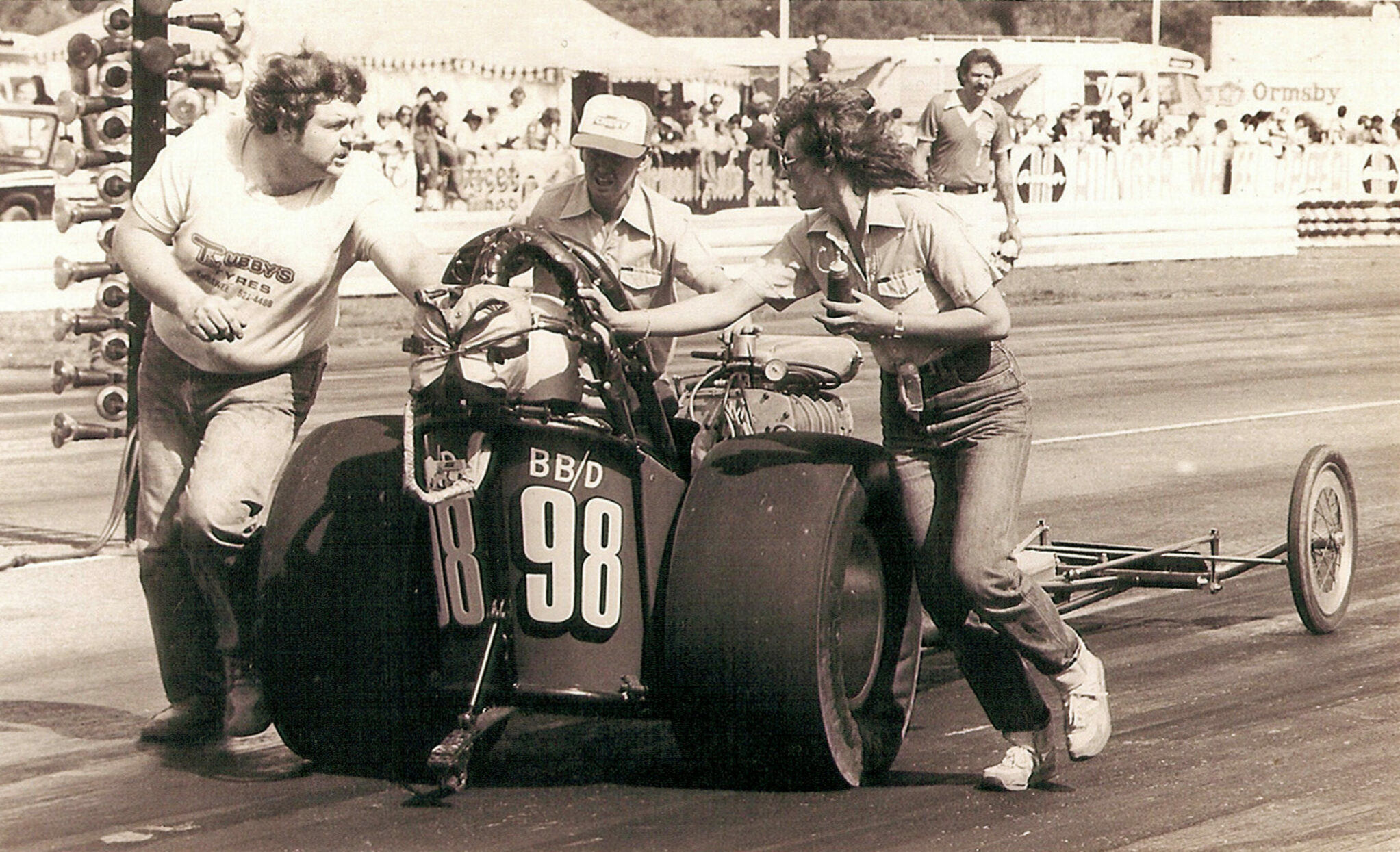

“Even though we enjoyed our hobby, we didn’t really throw a lot of money at it,” Ron explains. “We threw our labour and ideas at it. We made it run on the prizemoney. Even later on when we were running the blown Chev dragster, that’s the way we ran it, and we’d only put maybe a thousand dollars each into it each year. People would bring in a motor for reconditioning at Alan’s business and Alan’d say, ‘Oh, there’s a set of pistons we can use.’”

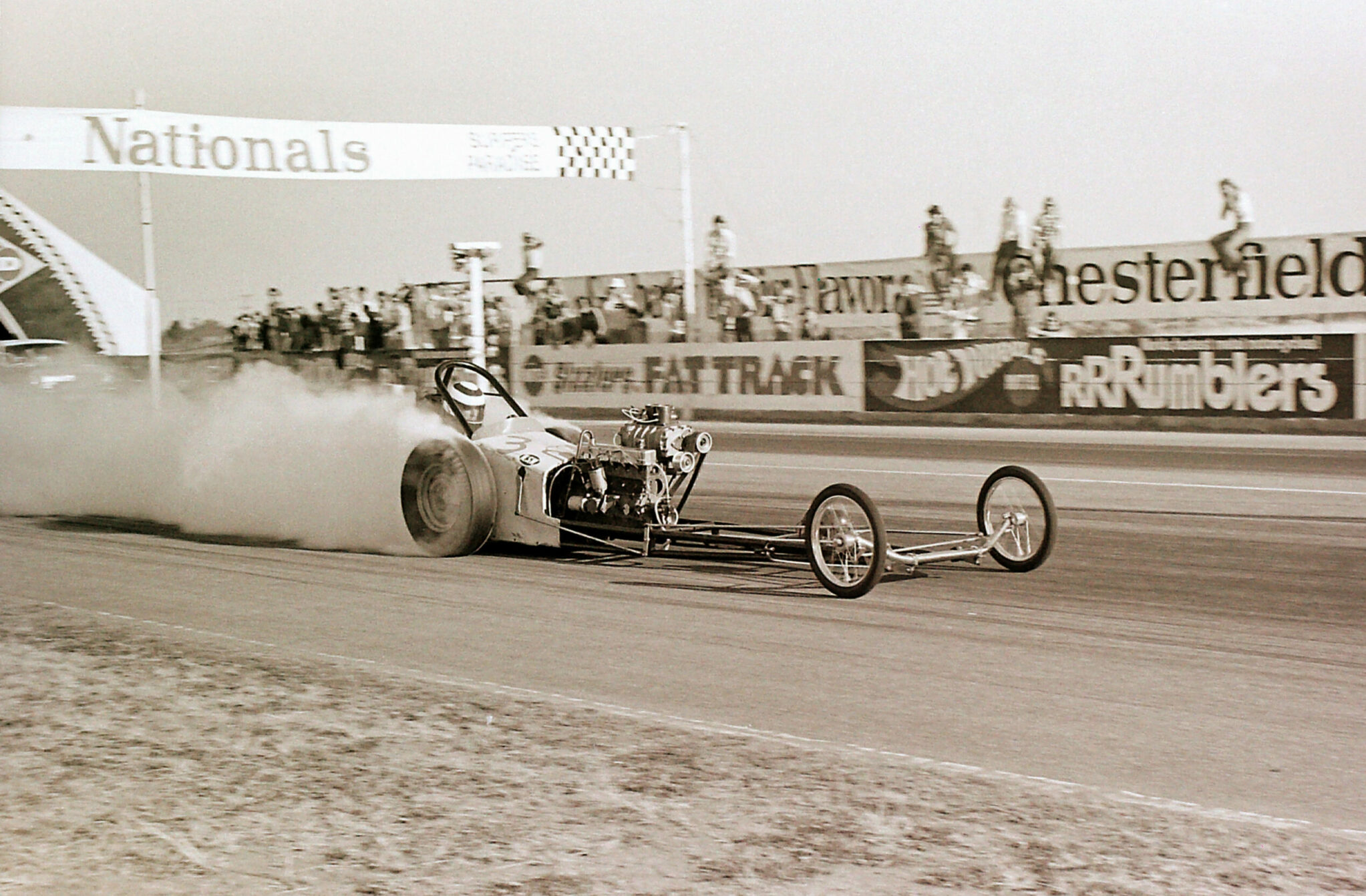

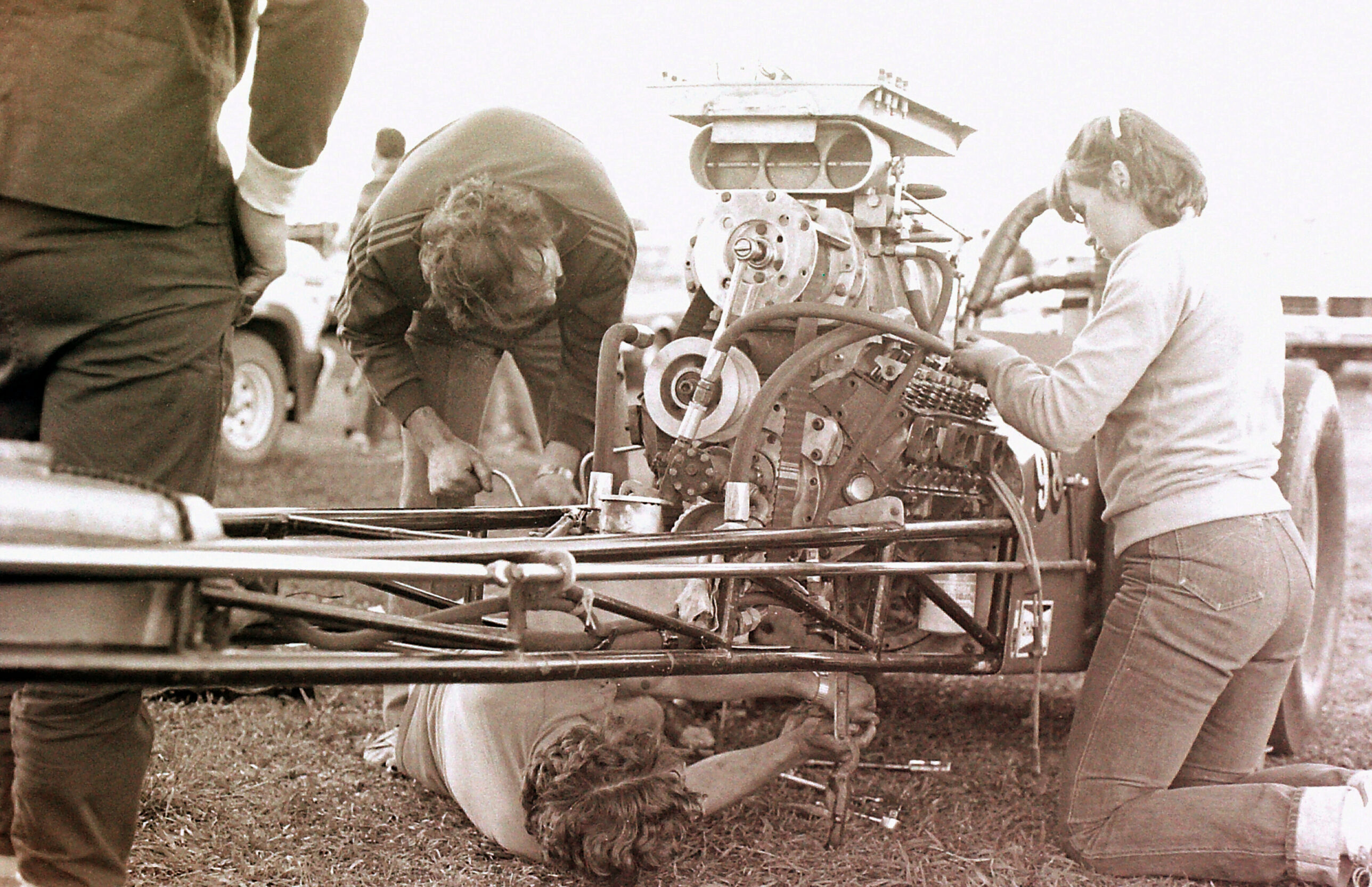

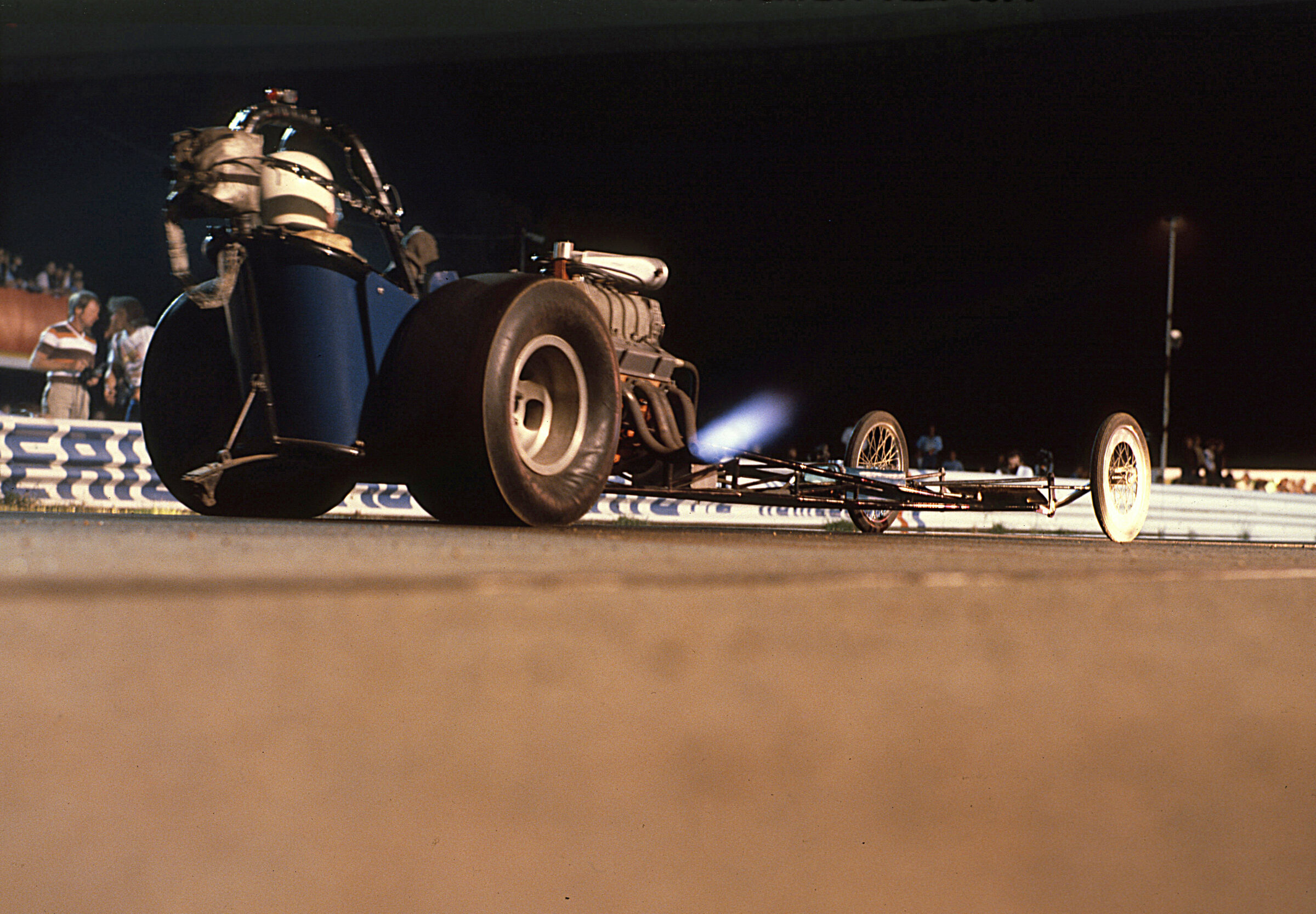

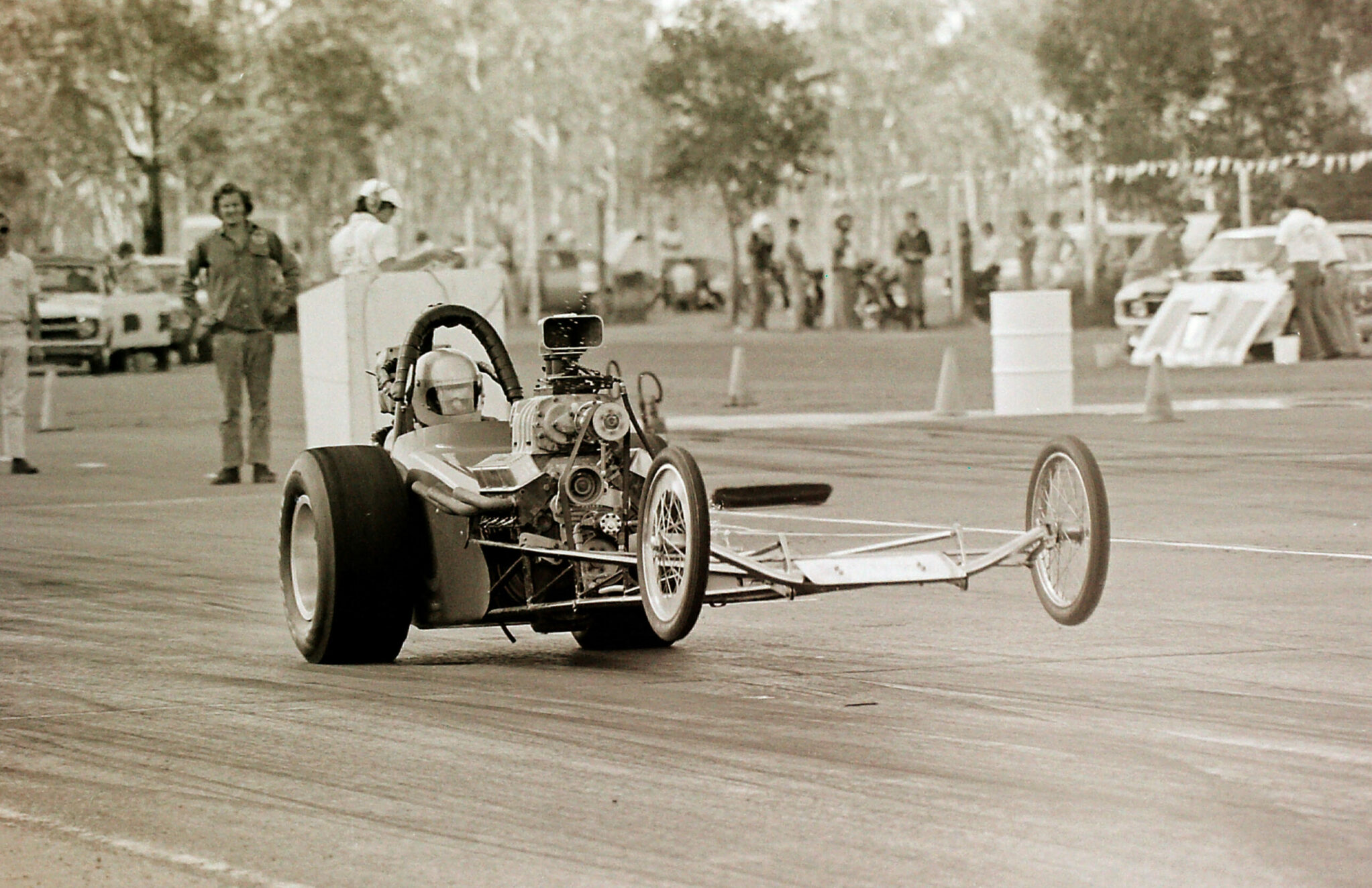

In early 1972, after five years of fun with the FJs, Ron and Wally switched to a dragster, which had been built by Warren Armour, with a blown Holden engine of their own construction. Its debut was at the ’72 Nationals, where it was amongst the star cars of the event, trailing smoke off the boiling rear tyres for half the track as it stormed to a runner-up place in Junior Eliminator behind Charlie Quagliata’s 430 Lincoln-powered dragster.

This car was to become well known for running ex-taxi motors, bought for $25 a piece after they’d done half a million miles, with the Moores’ head, cam and blower installed. If it threw the rods out, which it was prone to doing, well, it was no great loss at 25 bucks a pop.

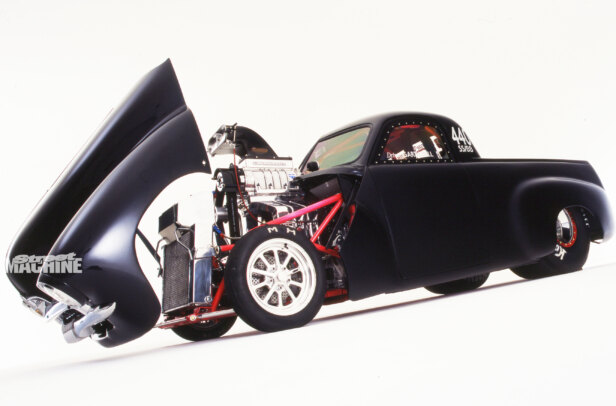

In 1975, they switched to a blown small-block Chev dragster that was to carry them on until 1984, when the Castlereagh track closed. The guys sat on the car for several years, but as time went on it looked as though there was to be no replacement drag strip in Sydney, so they sold it off in pieces and stepped away from racing.

“We went to a race meeting here in Sydney last weekend, and looking at the cars there, I wonder why anybody would want to talk to us about what we ran, because it seems to have so little to do with what runs at drag strips today,” Ron concludes.

“There are times when we miss the racing, but we couldn’t afford to do it like they do now. Even at the end of the Castlereagh era, it was getting to the stage where we needed a backer. We ran tyres ’til they were worn out, everything was run until it would go no further. We had a bit of mental telepathy going, and if I was working on the other side of the motor from Alan I’d just sort of know what spanner he needed next and it would be passed over just as he needed it, and he’d do the same for me.

“While we were racing, we were a team. We saw each other at least three times a week, every week, and now we don’t see each other anywhere near as much as we should, even though we only live six kilometres apart.”

“Our racing was a bond,” adds Wally. “A big bond.”

Comments