IF Street Machine is the bible of our sport, then Summernats must be Christmas, Bathurst and the Olympics rolled into one. There are stacks of other great events on offer around the country these days, but the Street Machine Summernats remains the biggest, wildest and most diverse of them all. If you want to immerse yourself in the full gamut of Australian custom car culture over four days, there’s nothing else like it.

First published in the January 2022 issue of Street Machine

The bloke we have to thank for it is Anthony Robert ‘Chic’ Henry. Chic founded the Summernats in 1988 and drove it like Brocky until 2009, when it was sold to new owners Andy Lopez, Dom McCormack and Andrew Bee. Now 75, Chic has remained involved with the event ever since, crowning each new Grand Champion and moving among his flock.

Where did the name Chic come from?

I’ve been called Chic since I was seven. I got it from a Warner Brothers character, Henery Hawk. He was the little chickenhawk, one of Foghorn Leghorn’s mates. So I was Henry the Chickenhawk, then Chickenhawk, then just Chic.

When did the car bug bite?

I grew up in Tasmania, and when I was about nine years old, my dad bought a 1937 Chev roadster. He painted it blue and, with the help of a couple of uncles, swapped a Bedford truck engine into it. I used to ride around in the dickie seat with my mates; we thought it was pretty cool.

Dad was always mucking around with cars, and he loved motorsport. We went to race meetings at the Baskerville and Longford circuits. I remember seeing Bob Jane’s E-Type Jag; it was the coolest- looking car, with massive rubber. Wow!

There were some cool car dudes in Launceston who rubbed off on me too, including Gene Cook, who became a Speedway champion, and Wayne Mahnken, who ended up being one of the early turbo gurus.

When did you get serious with cars?

I was more interested in swimming, diving and surfing when I was younger. I joined the army in 1964 as an apprentice blacksmith and bought a Morris Messenger van. I painted it with a brush, Mum made me some black satin curtains and I put a mattress in the back. It was ahead of its time as a shaggin’ wagon.

But my first real hottie was an EH Holden that I got in 1967. I put in solid lifters, a Cain manifold, twin carbies, Impala floor-shift and extractors. It could sit on 105mph, which was pretty good for a 179 back then.

What was the turning point that saw you join the car community?

I moved with my young family up to Townsville with the army in ’68. I got much more into the car scene up there and traded the EH in on a VE Valiant. I had the slant-six rebuilt with a big Wade camshaft, triple 13⁄4-inch SUs, and it had an original set of ROH mags that I hand-polished. I raced the Valiant at the Savannah strip and ran low 15s, which was pretty good in those days.

In 1969, I went to my first meet at Surfers while on holidays. I raced the Valiant there and met guys like John ‘Stomper’ Winterburn. Stomper drove an HD Holden with crazy graphics all over it – cars like that made a big impact on me.

When did you become a Chev guy?

I saw Col Neaton’s Ramcharger on the back of a trailer one time – it blew my mind and made me realise I had a thing for American cars. My first Chev was a ’57 I bought from drag racer Jeff Burnett; it had got caught in the 1974 Brisbane floods. He put it up on the hoist, but it still got flooded up to the turret. He washed it out with gallons of CRC, and it ended up being a pretty good car. It ended up with a small-block out of one of Jeff’s funny cars, and 10-inch-wide Ansen Sprints on the back.

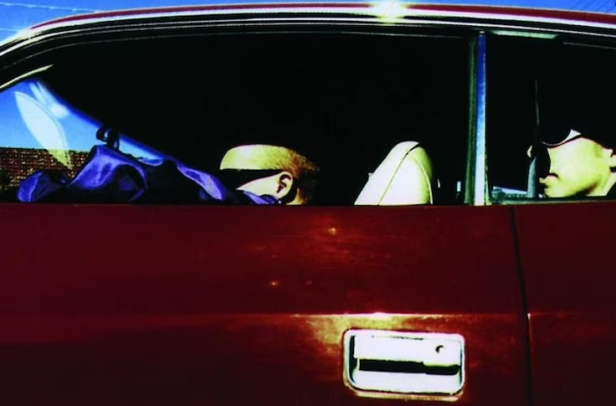

In 1978, I bought my ultimate car, a 1962 Chev Impala Super Sport. It was a 409/four-speed car, but the driveline was long gone, so I fitted a 427 big-block and a push-button 727 Torqueflite out of one of Bill Shrewsberry’s wheelstanders. I still love that car after all these years. I’ll see it in the shed or when I come back to it at the shops and think, “Man, I dig that Chev.”

When did you start getting into the organisational side of things?

I’d been involved in clubs through water polo, so that came naturally to me. I worked at Surfers as a scrutineer for seven years, but I was kind of caught between hot rodding, drag racing and this new street machine thing. The ’57 meant I was accepted by the hot rodders. I loved the drags but also liked the street aspect, and people like myself were starting to form clubs for these ‘late-model’ cars.

The first Street Machine Nationals in Griffith was put on by the 55-56-57 Chev Club of Australia in 1975. They ran it twice in Griffith, and then there was one in Shepparton run by the Victorian Street Machine Association.

The fourth Nats were held in Narranderra in NSW, which was run by Dave Ryan from Victoria, with help from me and Rowan Wilson from NSW.

That was the start of the states working together, so from there with guys like Rowan Wilson, Dave Ryan, Jim Wolf, John Toovey and others, we created a national organisation, the Australian Street Machine Federation, or ASMF. I became the national director. The Nationals had outgrown the smaller country towns, so we moved it to Canberra and ran it there in ’82, ’84 and ’86.

What was the genesis of Summernats?

I had moved to Canberra in 1985, because I really believed in the Street Machine Nationals. I’d been to the US Street Rod Nationals in Tulsa in 1976, and that got me thinking about what a large national event could be – an active event where people drove their cars, rather than a static show. Seeing that, and later the Street Machine Nationals in Du Quoin, convinced me that we could create something that was more like a festival, a celebration.

So you could see the ASMF Nationals becoming something like that?

Yes, but getting the states to all agree on anything was tough. It was a massive amount of work, so I negotiated to get paid to run the ’86 Nationals. For ’87, I put a proposal together to the ASMF, with the help of my late friend Rudi Vandenberg, to run the Nationals as a satellite to the Federation. But some people were scared of that or didn’t trust that someone was going to become a promoter – we’d all seen car show promoters disappear with the cash over the years. We were unable to move forward, so I put the call in to Street Machine, which had already sponsored the ’86 Nationals through editor Geoff Paradise. When Phil Scott took over as editor, he told me, “If you ever run your own event, we’ll partner with you and be the sponsor.”

How prepared were you to make the jump into full-time event promotion?

Besides what I had learned helping run the Nationals, I didn’t have a lot of experience. But I had learned a lot of different skills in the army. I also did some time working for a large funeral director in Brisbane. I was hired as a maintenance mechanic, but the rules of engagement when you signed on was that everyone on staff was trained to look after the bereaved. I found myself needing to become a much more understanding and compassionate person. I learned more about public relations from being a funeral director than anything else I’ve ever done.

How did you go about planning the first Summernats?

The program was the same as Street Machine Nationals; it was just a matter of enhancing it. Building a dedicated burnout pad was a massive undertaking. I had the might of Street Machine behind me as a huge marketing tool, but the critical thing was the special features.

Like what?

The biggest deal was bringing Rick Dobbertin’s Pontiac J2000 across from the US. It was the best pro street car in the world, so it was a massive draw. We also had a brand-new Walkinshaw as a raffle car. Those things needed their own promotion, separate to the event itself.

You must have had some good help.

For sure. Along with Rudi Vandenberg and John Pappas, I had a group of mates in Canberra who worked in the legal profession who were able to guide me on how to write letters, deal with insurance and so forth. Then there was the late Ronnie Whelan as chief scrutineer, Bill Giles at chief steward, Kit Laughlin on security and his brother Greg on financials. Over the years there were many more, like Michael O’Hara, Dennis Humphries, Chrissie Corkhill, Don Walker, Owen Webb, Steve Roland and Russell Avis. And my daughter Angie, who moved to Canberra to help me with the first one and has worked at the ’Nats ever since, right up to Summernats 33.

What were some of the bigger changes you made compared to the Nationals?

Professionalising the judging was a big one. Prior to that, judging was based on a tick sheet – anyone could do it. So we brought in professionals, including Rowan Wilson, John Strachan, John Taverna and many more great guys.

It was also important to add pure spectacle to the proceedings as well. For me, the biggest compliment was when people would ask, “What have you got planned for next year, Chic?” That’s why I kept looking for new and wilder things to feature, working with guys like Lawrence Legend to amp it up each time.

How did you go working with the authorities for all those years? Summernats was a pretty wild event back in the day, and still is in many ways.

Actually, it was really good. We had a working group with all the different government departments that met before, during and after the event. We worked out practical plans with them. Really constructive. It was a bit daunting when the era of risk management came in, but we figured out that everyone who was in charge of their part of the ’Nats was doing the right thing; we just had to formalise it.

Biggest mistake?

In 1993, we wanted to have a sacrifice for our show on New Year’s Eve. So we decided to sacrifice the most hated car, a Volvo. We whipped the crowd up and took the cover off to reveal the car. They went insane! We had it rigged up to make it drop off its suspension, then blow the bonnet scoop off and so on. I kept whipping them up (my voice has never been any good since that night), counted it down from 10 and blew it to smithereens. That was the end of the show; the crowd went off into the night and every Volvo in town was fair game. I learned that while you can wind a crowd up, you then have to wind them down.

1993 was the last year of the Supercruise, yes?

Yep. I came out in the ’62 at the head of the pack, and it soon became apparent that the crowd of people watching was just too big. People were moving across the road and there was no way we could control every intersection. Then there was the perennial problem of hangers-on joining in the cruise and mucking up. I had the feeling that the next year’s Supercruise could be a disaster, so we decided to bring it into NATEX for 1994. That made the government and the coppers happy.

How did the entrants feel?

It was a big ask, but I think the entrants had faith in me to do something reasonable – they could see it was better to drive the cars on the dirt than risk a potential WWIII on Northbourne Avenue. And that’s when we really cranked up the Saturday-night entertainment, to keep the crowds inside the venue as far as possible.

What do you think is the essence of the event?

That it is a tribal event. The entrants aren’t a homogenous group – you’ve got the Elite show car crew, the burnout guys, the dyno fans, the ones who just want to cruise and many more. So you can’t treat them all the same; you have to give them all some time in the sun. That part of human nature is what it is all about – the need to be noticed, whether you’re an entrant with a killer car or bunch of kids wearing watermelons on their heads. The ‘look at me’ factor.

What made you decide to step away from running the ’Nats?

After the huge 20th and 21st events, I knew we couldn’t keep doing it forever; the pressure was getting to me. When the time came to sell it, I didn’t want to deal with the stress of it anymore. I lived with it 365 days a year. The financial aspect was getting tough and every person who came in the gate was my responsibility. We ran a wild and crazy event for a long time and it was amazing we got away with it.

What was it like handing it over to the new owners?

Knowing their backgrounds, I had confidence in the new owners. My only question was whether they would understand the true nature of the event – that it is a coming together of cultures, that people’s whole lives revolve around it. But I knew they were professional and confident enough to make it work.

How do you look upon Summernats now?

I know how much it means to so many people – it means more to them than it does to me. It’s their mecca, which pleases me enormously. It is a wonderful thing to know that so many people got so much out of it. I’m so grateful to all those people who came to my party and enjoyed it with me.

Any words to live by?

Never let fear hold you back.

Comments