HINDSIGHT IS A wonderful thing. Part of the joy of this Modern Classic series arrives courtesy of the luxury of time and perspective. Not every car that we showcase here was an instant hit. There were cars that, at the time, failed to live up to the promise of their predecessors, such as the second-gen Toyota MR2 or the Ferrari 575.

Then there were cars like the BMW E36 M3 that diverged from a formula so far they initially confused the public. Once in a while, you get vehicles that came good at the very end of their parent model’s lifespan, by which time their equity in market was all but expended. They’re rarer beasts. For this, we present Exhibit A: the Tickford TS50.

The reason for its existence was simple. In 1999, the opposition, Holden Special Vehicles, introduced the 5.7-litre Gen 3 V8, in the process bumping power outputs up from 195kW to a strapping 255kW. Meanwhile the ageing Ford Windsor 5.0-litre V8 could only manage a peak of 220kW and in this sector of the market, big numbers really mattered.

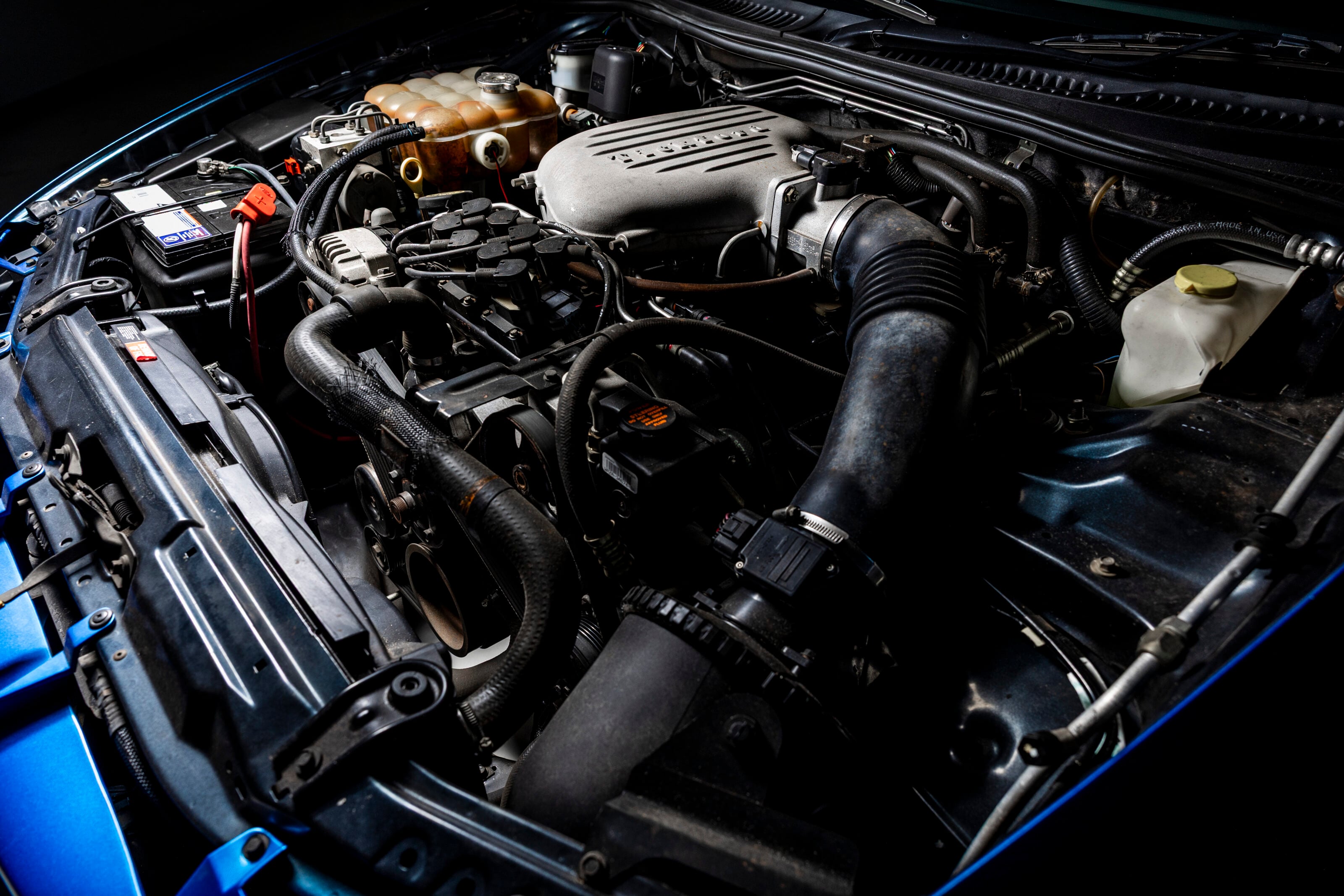

Built on the third-generation AU Falcon, Tickford’s clap back involved a comprehensive reworking of the Windsor V8. Supercharging, turbocharging and enlarging the capacity of the engine were all options on the table at the time, but forced induction was eventually nixed on the basis that the target customer would prefer a larger capacity powerplant. Stroking the engine was deemed the best solution, bringing prodigious helpings of torque in the process and endowing the motor with a more muscular feel.

The engine modifications were more than a mere stroking though. Tickford really threw everything it knew at not only generating more power and torque, but doing it reliably and with driveability in mind. Tickford realised that due to the limitation of the BTR LE97 automatic transmission, a 500Nm torque ceiling was what it had to work with. The challenge from there was to eke power upwards while respecting that torque limit.

It was clear early on in the piece that the old T5 manual ’box wasn’t up to that particular task, so the Tremec TR3650 – as seen in the 2002MY Mustang – was sourced, and a custom adaptor house was cast for it, in order for it to mate to the old T5 bell housing.

Australian suppliers worked with Tickford to supply a new crank, rods, pistons, heads, camshaft, inlet manifold and throttle bodies. From there, each of these ingredients were hand-assembled in order to create the 5.6-litre stroker powerplant. The difference in the way this engine was developed compared to the base 5.0-litre units in the XR8 were stark.

Whereas an XR8 usually requires frequent oil tip ups, the 5.6-litre isn’t afflicted. Why? Because as soon as the iron blocks were received, Tickford stripped them down, cleaned them and treated them to a torque plate honing that opened the bores out to 101.67mm. A set of ARP studs and a custom stud girdle were fitted to the main bearing tunnel in order to create a rigid base capable of handling that 500Nm torque reaction. The 86.4mm long-stroke crank, worked on by Crankshaft Revolution, is key to proceedings, while Precision Parts of Wagga Wagga supplied the uprated harmonic balancers.

The conrods are a particular work of precision art, being created from a single billet by Argo in Newcastle before shot peening and machining. ACL supplied the bearings and pistons, while Crow Cams developed a version of the Ford’s F1ZE cam with the lobe timing retarded by three degrees. Each engine was entrusted to a single builder who, in true AMG or Aston Martin style, got to have their name on a plaque on the car’s engine.

Perhaps the greatest technical challenge in the process was honing the engine’s breathing. Tickford initially believed that the original intake manifold could be modified in order to feed the greater swept capacity, but after several iterations it was apparent that both the through-flow and the plenum volume were inadequate for the task at hand. An entirely new part was needed. Ford rendered assistance with a computer simulation that effectively confirmed Tickford’s issue, and developed a CAD file that pointed to a successful resolution.

It was found that the stock plenum would starve the engine when the throttle was quickly opened, but going too large compromised response, as the mass air flow sensor would then take a beat or two to accurately measure conditions. Tickford was also keen to retain the standard injectors, but fuel pressure was increased from 2.8 to 4.3 bar, so that fuelling could match the bigger 82mm throttle bodies. When the results came good it was found that the 5.6-litre lump would develop more torque at 1800rpm than the old 220kW T-Series could boast when at flat chat.

Wheels got to ride with Tickford’s engineers on pre-production hot weather testing of the 5.6-litre engine back at the tail end of 2001. Based in Katherine, NT, the TS50 sedan and ute mules were punished in a hot tent, made to tow a dyno rig for hundred of kilometres at 45km/h – deemed the least efficient speed for engine cooling – and set to cruise at the hottest parts of the day at 220km/h for hours on end, the latter test to assess fuelling, finesse engine oil requirements and finalise radiator top tank specifications.

The Wheels treatment

The acid test came in January 2002 when Wheels put the TS50 up against the obvious competitor, the VX-based HSV Clubsport R8. Both were manual sedans, and both were priced identically at $66,950 before options and on-roads. With 24kg less to haul up the road and 5kW more to boot, the HSV leveraged a 149kW/tonne on-paper advantage versus the Tickford’s 145kW/tonne showing, but the Tickford 25Nm torque advantage made it anyone’s guess which would prove quicker. On a chassis dyno, the Tickford made 205kW and the Clubsport a hefty 226kW at the wheels.

Against the stopwatch, the TS50 drew first blood, notching a 6.3 second 0-100km/h time, while the HSV clocked 6.5 seconds. For the 400m sprint, the Tickford would still be hauling in third as it crossed the line in 14.6 seconds at 156km/h, while the closer-geared six-speed HSV would require a grab for fourth, which meant it was just pipped, registering 14.7 seconds at 159km/h. In truth there’s precious little in it in terms of straightline speed.

Out on track on Oran Park’s short circuit with gun driver Peter McKay behind the wheel, the two cars got one warm-up lap, three timed laps and a cool-down in-lap to show their stuff. Our man much preferred the feel of the TS50’s Tremec manual compared with the lower-spec Tremec T56 six-speeder in the HSV, although the extra ratio meant that on the two key corners bookending the main straight, the R8 was comfortably into third where the TS50 was near banging the limiter in second, third feeling way too tall. Thus compromised, the HSV squeaked home with a 0.2 second advantage.

“While the Ford feels way more stable and composed under brakes and puts its power down better, it is handicapped by some missing horses (race drivers, eh?) and that way-too-tall third gear,” McKay opined. “Those couple of extra gear changes would, I imagine, account for those extra two-tenths. At another circuit, on another day, the outcome could well be different, provided the corners better suited the Ford’s gearing.”

Road tester Mike McCarthy noted that the Koni-damped TS50 rode more firmly than the comfy R8, but it leveraged a key benefit when it came to driver feedback. “Ride apart, the TS50 has the more responsive chassis, the more decisive and better balanced handling, and the more directioned steering,” he noted, some of the detail calibrations coming from hours of testing and feedback by Aussie tin-top hero John Bowe. “The Ford has the sharper focus at straight ahead and unsullied connection between steering wheel and road. The HSV feels a bit detached on centre and doesn’t steer quite as crisply. When cornering, the Ford sits flatter, grips harder, carries more speed with more confidence, and there are constant cues that this is what it’s made for. Scything through turns as if tracing French curves – tyres biting and engine yowling with forceful enthusiasm – the TS50 is every inch the sports sedan.”

He concluded by saying “There’s no argument about this TS50 having the looks, brawn and balls to hit the R8 where it hurts. On the road and in the driving, for sure. And, by rights, in the showroom.”

Limited runs

But while HSV shovelled Clubsport R8s out of its Clayton plant by the thousand, the TS50 Series III’s hand-fettling meant that it wasn’t a car that could be rushed through the production process. In all, just 224 were built, including four prototypes. Aside from these development cars, the production run was split between 70 manual-equipped cars and 150 automatics.

The 5.6-litre XR8 Pursuit 250 ute you see here is rarer still, with only 54 ever built. Both the cars here are owned by David Earl, a Melbourne-based enthusiast who prefers putting his money into rare metal than trusting a super fund manager. Both are finished in the wonderful and apt Blueprint colour scheme, which accounted for more than a third of all Series 3 TS50 production. The other two new colours added for Series 3 production were Congo Green and Monsoon Blue joining Narooma Blue, Winter White, Meteorite, Mercury Silver, Liquid Silver, Silhouette and Venom Red.

Ford offered the standard wheelbase sedan in both TE50 and TS50 guises. The cheaper TE50 retailed at $57,350 for the manual or $58,350 for the auto, compared with $66,950 for the flagship TS50. Both cars featured the no-holds-barred 5.6-litre stroker powerplant, and identical suspension and driveline, although the Koni dampers were a $1500 option on the TE50 and standard-fit on the TS50. The only difference in the standard brake setup was that the TE50 got a three-channel ABS system and the TS50 a four-channel arrangement.

What’s more, the ESS sequential-style shift was reserved for the TS50. The uprated Brembo brake package (four piston calipers all round, Textar 4000 pads and cross-drilled rotors of 355mm up front and 330mm at the rear) was a hefty $5350 extra on both models and while the TE50 got an Alpina-like 18-inch turbine alloy wheel as standard, the TS50 featured an arguably more dynamic-looking five-spoke design. Indoors is where you’ll find significantly more differences, largely because the TE50 was spawned from a more prosaic Falcon donor whereas the TS50 started life as a Falcon Ghia and so has climate control rather than air-con and so on. It also carries a 15kg weight penalty as a result.

The XR8 Pursuit 250 was priced at $54,250 for a manual model or $54,912 for the auto. You could also specify the Brembo brakes for this, the other key option being a hard tonneau cover which would set you back $2750. In case you were wondering, no, the ute’s not lighter than the sedan, largely thanks to the heavy duty leaf springs out back. It also got an 82-litre touring fuel tank versus the sedan’s 68-litre unit. Model for model the pick-up’s around 15kg heavier than the TS50.

For the collectors

Unfortunately, you’re a little late on the draw if you were looking to bag a Tickford TS50 at the depth of its depreciation curve. The launch of the FG Falcon in 2008, supplied with a 270kW/533Nm turbo-six that eclipsed the 5.6-litre stroker unit’s numbers, corresponded with the nadir of Tickford T-Series values, but since then the market has changed. First there was the frenzy in Falcon speculation that accompanied the demise of the FG-X and that went hand-in-hand with a gradual recognition of the talents, exclusivity and focus of the TS50. Even today, you won’t find a Falcon that’s a sweeter steer than these late-era AU models.

Should you decide to take the plunge, prices start at around $45,000 for cars in reasonable condition which, given the rarity and specialist nature of these cars, still feels criminally undervalued. A BMW E39 M5 of similar vintage and mileage would easily be double the price, and these are relatively commonplace cars in comparison. Indeed it was the 5 Series that was initially benchmarked in the development of the first AU FTE (Ford Tickford Experience) models.

Because it was engineered for Australian conditions, TS50s tend to be rugged beasts and due to the fact that there’s significant overhead in their valuations, most have been looked after, latterly at least. Paint has often been a complaint, with the Venom Red cars suffering particularly from fading and all paint finishes susceptible to milky clear-coats. Panel fit was also iffy around the custom front and rear clips, and door hinges can drop. Although most of these cars will now live in a garage, rust is something to check for. Seams, chassis rails, strut towers, boot floor, windscreen bases, beneath the number plate, under rubber seals, inner guards, engine bay – you name it, it’ll need the once-over. Galvanisation was not in Ford’s vocabulary at the time.

The interiors are generally reasonably hardwearing, but turn of the century electricals will need checking. LCD panels on the trip computer, climate control and odometer need to be given the once-over to make sure all characters appear and the readouts haven’t dimmed. The bolstering on the leather seats can also be prone to wear and central locking, temperamental.

Mechanically, the 5.6-litre engines are robust but check for water and oil leaks. Cars without the optional ‘Ultimate’ Brembo brake package could warp their 329mm front and 287mm rear discs if driven hard, while higher mileage automatics need to be checked for any suspicious clunks or unacceptable driveline shunt.

The Tickford TS50 Series III didn’t live a long life. Within seven months of Wheels’ first comparison with the 5.6-litre hero car in the January 2002 issue, the next-gen BA Falcon was already featuring on the cover of the magazine. It seemed a heck of a lot of effort to go to in order to build such a limited run of cars and, in truth, it was. Ford Australia’s boss, Geoff Polites, had come under extreme pressure from the Dearborn mothership to turn things around, and the problem child was the AU Falcon, outsold by the VT and VX Commodores, ceding a lead in the market that even the commercially smarter BA couldn’t claw back.

It was this AU malaise that, for a long time, tainted the reputation of the Tickford TS50. It carried the aura of reflected failure. As we can now appreciate, that was far from the case. The Series III TS50 achieved exactly what it set out to in terms of giving HSV a black eye and is right up there with the most special sporting sedans that Australia ever produced. It deserves to be recognised for the excellent driver’s car that it is. Time, as ever, has been a wonderful healer.

This article originally appeared in the June 2025 issue of Wheels magazine. To subscribe, click here.