Do you ever wonder which year, as a car enthusiast, you’d most love to be teleported back to? Of course, there’s an argument that we’ve never had it as good as we’ve got it now, given that cars are quicker, more comfortable, more capable, more reliable and safer than ever, but I’d set the dial on our imaginary time machine back to 1994.

I’d watch Ayrton Senna set pole in front of his home fans at Interlagos and Michael Schumacher win the race, witness owners being presented with their box-fresh McLaren F1s and take a drive in the all-new Ferrari F355, the car that turned around Maranello’s fortunes. The daily driver? That’d be a car that Volvo first showed late that year: the astonishing 850 T-5R.

It was far from the fastest wagon launched in that particular era. In March 1994, Audi had comprehensively upped the ante with the 232kW RS2 wagon, a vehicle developed and assembled in conjunction with Porsche. Notwithstanding the Nogaro Blue missile from Rossle-Bau, the backstory behind the 850 T-5R is arguably even more interesting. There was certainly a good deal more consequence to it.

We talk a lot about ‘make or break’ cars and, in many instances, it’s a case of gentle journalistic hyperbole. The Volvo 850 was a genuine case and given Volvo wasn’t a company given to wild gambles, it had a very long and deliberate gestation, starting in 1978.

In April of that year, the newly appointed CEO of Volvo, Håkan Frisinger, called a meeting with his most trusted colleagues in Gothenburg. The backdrop was one of pure Scandi-noir bleakness. The global economy was dragging itself out of the second oil crisis, the proposed merger with Saab had failed, the Swedish government had turned down Volvo’s request for a billion-kronor line of credit and the government had doubled down by issuing a report claiming that Sweden’s car industry could only survive by producing smaller and more affordable cars, and in the USA.

Frisinger was unusually bellicose, exhorting his colleagues to ignore short term headwinds. “Now is the time to look at least 10 years ahead,” he urged. “Despite the difficult economic situation, we must prepare ourselves. We must assume that Volvo Cars will succeed. And by doing so, we will also ensure survival… Let’s use the 1980s to reverse the negative trend and instead make ourselves truly strong in terms of products, competence, quality, organisation, and industry.”

Slowly does it

Project Galaxy, as the development was codenamed, set out to spawn two new cars: the large 850 and the smaller 400 series. As is often the case, scope creep occurred and Volvo found itself not only commissioning a new modular engine series, but also a transmission and a whole host of new safety features. The budget for Project Galaxy blew out to such an extent that it became the most expensive capital project in the entire history of Sweden at 16 billion kronors. So no pressure then.

No panic either. After all, Volvo doesn’t do revolutions loudly. When it does turn the ship, it’s with the slow, deliberate motion of an aircraft carrier rather than the flick-spin of a speedboat. And yet, behind the conservative lines of the Volvo 850 lay a vehicle so fundamentally different from its predecessors that it might as well have been a moonshot.

There was no great rush. That 1978 meeting merely lit a slow-burning fuse. The official green light for Project Galaxy came in 1986. What followed was nothing short of a reinvention; from industrial tooling to mechanical architecture. Assembly would be split across Europe: Ghent, Belgium for the car itself, while the beating heart – the engine and transmission – would be born in Skövde, Sweden.

This was no mere facelift. The 850 would break with Volvo orthodoxy in dramatic fashion. For the first time in a large Volvo, front-wheel drive would be the order of the day, and beneath the bonnet, a transversely mounted engine. Not just any engine, either, but a five-cylinder. An unusual configuration then, and even more so when mounted sideways, although a certain community of Ingolstadt engineers may well beg to differ.

At a time when most mainstream manufacturers were playing it safe with four-cylinder mills, and when they weren’t, defaulting to V6s, Volvo followed Mercedes-Benz, Volkswagen, Honda and Audi in taking the path less trodden. The 850’s engineers were targeting a smooth, torquey 2.5-litre powerplant, but pushing a four-pot beyond two litres without excessive noise, vibration and harshness meant paying Mitsubishi royalties for their ‘Silent Shaft’ balancer shaft design (as Porsche did with the 2.5-litre that went into the 924S and 944 models). Volvo thought it could do better.

The first engine from this modular family was the six-pot B6304F which debuted in August 1990 in the Volvo 960. The five-cylinder variant, dubbed the B5254F, was more characterful than a four, more compact than a six, and far more interesting than either. With 127kW on tap, it wasn’t going to set Nürburgring lap times, but that was never the point. The 850 was about intelligent compromise and engineering elegance.

Of course, shoving a five-pot across the engine bay meant space was tight. The packaging challenge was acute, especially when it came to the transmission. Volvo’s response? A three-shaft manual gearbox.

Unorthodox, yes, but clever. Instead of the usual two-shaft arrangement, engineers added a second intermediate shaft, allowing them to shorten the gearbox to just 353mm in length. It weighed a paltry 46kg and needed so little upkeep, oil changes were almost an afterthought.

It wasn’t just a gearbox. It was proof that Volvo’s engineering team was thinking differently, holistically, and often well ahead of its time. Aisin was contracted for the four-speed automatic transmission, a key component if the 850 was to sell in significant numbers in the key US market.

The 850’s launch in June 1991 wasn’t just about resetting the company’s datum on drivelines. It also ushered in what would become a key Volvo safety innovation: the Side Impact Protection System, (SIPS). Unlike competitors’ bolted-on solutions, Volvo’s approach was integrated from the get-go. Energy from a side impact would be dispersed not just through the door structures, but into the B-pillars, seat frames, underfloor beams, and a central SIPS box nestled between the seats.

It was a complex choreography of materials and structure, all working in unison to do one thing: protect. The concept had been patented by none other than Nils Bohlin, the same safety savant responsible for the three-point seatbelt way back in 1974. With the 850, that vision was realised. And by 1995, seat-mounted side airbags took it a step further, long before rivals were offering anything comparable.

For all this under-the-skin innovation, the 850’s styling was, to the untrained eye, distinctly… familiar. That was by design. Jan Wilsgaard, Volvo’s head of design since 1950, was overseeing his final project for the brand, and his instinct was to let the engineering take centre stage. The shape, a gentle evolution of the 700 Series, was undeniably conservative in its proportioning and surfacing, assuring loyalists that while the car may be all-new underneath, it was still undeniably a Volvo.

Wilsgaard partnered once more with Turin-based coachbuilder Coggiola, softening the edges slightly, but resisting the temptation to follow design fads. True visual transformation would come later under Peter Horbury’s tenure, beginning with the S40 and culminating in the sleek and curvaceous C70 coupe of 1996.

The 850 sedan was launched in late 1991, with the wagon body following in 1993, with all versions getting a mild facelift in 1994. In August 1994, a 166kW turbocharged petrol sports model was launched, dubbed T-5 in some markets and, with typically Swedish pragmatism, badged Turbo in others. Demand for the T-5 outstripped Volvo’s ability to supply, the 850 chassis handling the additional power without a skerrick of torque steer. It rapidly became a favourite pursuit car for police forces around Europe.

Volvo is… cool?

The launch of the T-5 also kickstarted a new, more dynamic image for Volvo. The company’s Back on Track project was launched in April 1994, when two Volvo 850 wagons fronted up at Thruxton circuit for the opening round of the British Touring Car Championship (BTCC).

Tom Walkinshaw Racing, which had been Volvo’s main competitor in the European Championship series during the 1980s when the 240 Turbo was competing against the Rover SD1, had been contracted in 1991 to develop a tin-top race car. Richard Owen, the man who also designed the stunning Jaguar XJ220 body, was put in charge of designing the 850 racer. TWR would provide the hardware and Volvo would be responsible for technical support, marketing and PR.

The decision to enter the competition with two wagons was made several months before the start, but it was kept under wraps until the last possible moment. When the news broke, many assumed it was a joke. After all, a large wagon is far from ideal for the track, with extra weight behind the rear axle and the long roof creating a higher centre of gravity, it was certainly an unconventional choice, especially given a sedan option was available.

“But the aerodynamics of the estate were actually slightly better [than the sedan],” recalls driver Rickard Rydell. However, the real deciding factor was the attention the wagon would attract. Under FIA Class 2 regulations, race cars had to be based on production models. The body shape could not be altered, and to keep the races competitive, engine displacement was limited to two litres, maximum engine speed capped at 8500 rpm, and minimum weight set at 950kg for front-wheel-drive cars. Forced induction of any kind was strictly prohibited.

Volvo and TWR chose to base their car on the five-cylinder engine found in the 850 T-5, which originally had a 2.3-litre capacity and produced 166kW and 300Nm. The racing version, naturally aspirated and reduced to two litres, produced 216kW. The standard five-speed manual gearbox was replaced with a six-speed sequential transmission. Notably, Volvo was the first team to fit its cars with catalytic converters, which later became mandatory under class regulations.

“We didn’t have time to properly test the car on track before its debut at Thruxton on April 4,” says Rydell. “Jan Lammers and I had only managed a few hundred metres outside TWR’s development workshop – that was it. The 850 estate was by far the biggest car in the championship,” Rydell explains. “Most competitors, who were mainly there to enhance their sporting image, weren’t thrilled about going up against an estate car. There were a few jokes and jibes from other drivers – but that didn’t bother us. In fact, just to tease them, we drove with a large stuffed collie in the boot during the parade lap at one event.”

The wagon wasn’t the most successful race car, but you could be excused for not realising that, given the column inches it claimed. It was 14th in its first season, and was then switched out for the 850 sedan, which came third in its two campaigns.

Enter the hero

Cue the T-5R. Originally dubbed the 850+ and the 850 plus 5 (the name that appeared in the original press kit), this wicked-up version of the 850 T-5 also lived for but one year of production. By now you’ll have realised that the claim the T-5R was some sort of homologation car to allow Volvo to go racing is a furphy.

With power edged up to 177kW and torque to 330Nm, the T-5R featured an uprated ECU, which saw boost pressure cranked up from 9.6 to 10.9psi, allowing up to 7 seconds of full-bore grunt. The car sat on lower and stiffer springs and also featured a deeper front spoiler with inset fog lamps, and graphite grey alloy wheels shod with 205/45 ZR17 Pirelli P Zero tyres. Only two options were listed: An Alpine 6 CD autochanger and 16-inch wheels with Michelin MXM all-weather tyres. Supply was strictly limited, as Volvo’s hilariously terse press release accompanying the car’s launch outlined.

“It is not going to be a volume seller. Which explains why you are not going to see it that often. That is not the idea when it comes to the 850 T-5R. Only 2500 people will be given the privilege of owning this specially-prepared turbocharged model because only 2500 cars will be produced,” it stated. Of that initial production run, Germany and Italy were the biggest markets, with 876 going to the USA, 200 earmarked for the UK, and a mere 25, all manuals, and all in signature Cream Yellow, would come to Australia.

Our allocation was interesting. Volvo Cars Australia was keen for the T-5R to make its mark in Super Production racing and offered the T-5R sedan for $74,950 in race-stripped guise, or $75,950 for the roadgoing car with items such as air conditioning, a sunroof and rear seats present and correct. Volvo paint code 607 was also changed by VCA from the original Cream Yellow name to Faded Yellow for Aussie customers, with Volvo USA also changing the name of the paint finish to T-5R Yellow, apt as it’s the only Volvo it ever appeared on. Rather than worrying about what the paint was called, perhaps VCA should have been paying more attention to what BMW and Frank Gardner Racing were working on: the 235kW E36 M3R, a car so powerful and capable that Volvo’s domestic motorsport aspirations were summarily blown out of the water.

The tuning of the Bosch 628 ECU for the 850 T-5R endowed it with a peakier torque curve than the garden-variety T5. Whereas the T5 developed its 300Nm in a broad plateau from 2000 to 5250rpm, making it a very easy car to keep on the boil, the T-5R’s 330Nm arrived between 3000 and 4800rpm. It was enough to get it to 100km/h in a claimed 7.0 seconds, half a second quicker than the stock T5.

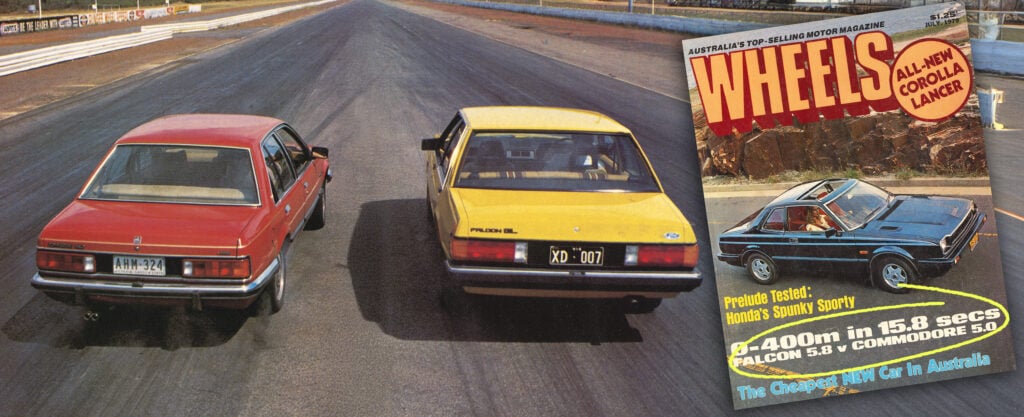

The redoubtable Michael Stahl was our man on the spot for the T-5R road test, which ran in the January 1995 edition of Wheels. He seemed a little nonplussed at the brawny Swede, noting its doughy throttle response, remote steering and long-throw gearbox.

“Maybe that’s just our fault for expecting a Swedish BMW M3,” he wrote. “The T-5R is a textbook performance front-wheel drive handler: Neutral with eventual, usable understeer on fast exits and a tail that’s unfussed by desperate late braking and flick corner entries. Body roll is notably well controlled; so too is the body’s squat and dive under acceleration and braking.

“Heck, but the Volvo from Hell rides really well. Remarkably so, in fact, given its firm and confident handling and those low-profile Pirellis. It doesn’t rumble at all noisily or uncomfortably over patchy surfaces, nor does the steering tramline. If anything, its bump damping might be just a tad too firm and its rebound just a tad too soft, which allows a mild hopping motion over undulations. Generally, however, it’s a remarkable achievement.

“The standard 850 T-5 model is blessed with more brakes than it could ever need, a fact made evident to this punter during dozens of laps of Phillip Island a year ago. Volvo deemed the ventilated front, solid rear disc set-up (with four-piston calipers up front) sufficient for the R-car, and we’ve no complaints in terms of fade or feel.”

So, a solid report card for go, stop and steer. We had another crack in the T-5R couple of months later in the May 1995 edition, when the Volvo joined a host of other performance cars for the Wheels Speed Fest ’95 feature. We slotted Peter Brock behind the wheel of that year’s latest and greatest and set him loose on Lang Lang’s high-speed bowl. Lurid tales of 850 T-5R development drivers harassing Porsches on autobahns had been whispered about for years. Now it was time to put up or shut up.

Brock squeezed 258km/h out of a 993 Carrera 4 around the banked circle, and the all-wheel drive Porsche also stopped the clock at 14.2 seconds over 400m. The Volvo couldn’t get close to those figures, running into an aerodynamic brick wall at 231km/h and clocking 15.6 seconds over the quarter. The feature speculated that the Volvo suffered from the heat on the day: “The placement of the exhaust manifold, including turbocharger of course, on the rear side of the transverse five certainly looks like a recipe for heating the long and serpentine induction tract.”

A slight lack of apparent horses aside, Brock was impressed by the T-5R’s manner, noting that it was a more agreeable thing to pedal than the unruly Saab 9000 Aero also along for the event. “Turns in better than the Saab coming into the off-camber corners,” he noted. “Very chuckable car to drive. I’d say less understeer than the Saab. Unlike the Saab, the back end is doing a bit of work. It’s actually helping to unload the front. Yeah, a better job from a handling point of view.”

Brocky knew these hot Volvos well, having campaigned in a 2.5-litre T-5 sedan at the 1994 Bathurst 12-Hour (his race ending with transmission failure), and later went on to campaign a 2.0-litre 850 in the 1996 Australian Super Touring Championship. The car was an ex-Rickard Rydell BTCC sedan and Brock’s best result that year was a second at Lakeside, eventually finishing sixth in the title race. He missed the Bathurst 1000, concentrating on his Holden Racing Team commitments instead, with Jim Richards slotting into the seat and winning the wet final race prior to the 1000, giving Volvo its first victory in Aussie Super Touring.

By modern standards, the 850 T-5R is not a particularly quick car, but it’s one that handles neatly and has never quite lost its capacity to surprise, especially in wagon form. It stands as a milestone; not because it shouted, but because it didn’t need to. So successful was the T5-R that Volvo massively exceeded the projected 2500 car production run. In all, 5500 cars were built for world markets. Of these, 1975 units were Cream Yellow, 500 were Dark Olive Pearl and 3025 were finished in Black Stone.

Above all, the T-5R redefined what a Volvo could be: smart, safe, and just a little bit subversive. This element of nod and wink lends it enormous charisma and was perhaps the moment Gothenburg showed it could think like Stuttgart, but with a conscience. In doing so, it laid the groundwork for the brand’s modern era.

In effect, you’re looking at the moment that Volvo rediscovered its mojo.

The Porsche angle

There’s some lively debate on exactly how much involvement Porsche had in the development of the T-5R. Some maintain that Zuffenhausen’s consulting engineers were involved in fine tuning the intake and exhaust manifolds, and there’s also some evidence that they worked on the ECU tuning. The suede-like Amaretta interior finish came straight off the reel that Porsche used on the 993 Turbo, which was also introduced in 1995. Oh, and the fold-out cup holder is a little bit of Porsche ingenuity too.

Specs

| Model | VOLVO 850 T-5R wagon |

|---|---|

| Engine | 2319cc inline-5, DOHC, 20v, turbo |

| Power | 177kW @ 5600rpm |

| Torque | 330Nm @ 3000-4800rpm |

| Transmission | Five-speed manual/four-speed auto |

| OE tyres | 205/45 ZR17 Pirelli P Zero Asymmetrico |

| L/W/H/WB | 4710/1760/1430/2664mm |

| Suspension | Struts (f); Semi-trailing arms (r) |

| Kerb weight | 1451kg |

| 0-100km/h | 7.0s |

| Price | (now) from $30,000 |

This article originally appeared in the October 2025 issue of Wheels magazine. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesModern Classic: BMW M Coupe

It’s attracted some cruel nicknames but when Wheels first encountered the BMW M Coupe in 1998, we knew it was something special.

-

Features

FeaturesModern Classic: Nissan Skyline R33 GT-R

The awkward middle child of the 'Godzilla' triumvirate or the Skyline GT-R for those with a more discerning eye?