Bugatti built its first production Veyron 16.4 in 2005, back when John Howard was Prime Minister.

At its astonishing top speed, even limited to 407km/h when it launched, it ate 45,000 litres of air a minute, which was also quite similar to Howard when he got on a roll. And now it has finally joined the politician in retirement, with Bugatti last month selling the last of the 450 Veyrons, a 16.4 Grand Sport Vitesse roadster dubbed La Finale.

The 1888kg carbonfibre monster ended production with 300 coupes and 150 roadsters on the road, leaving Bugatti as a brand without a saleable car. That won’t last for long, though, with Bugatti President and CEO, Wolfgang Durheimer, promising it will be back with another coupe based on the same engine. But faster and lighter. With more power, more torque, more focus. And, well, just more of everything.

“More breathtaking” is an extraordinary statement to make. There have been few parallels in the history of the car industry to match the impact made by the Veyron’s “breathtaking-ness”. Maybe McLaren’s F1 made the same sort of impact, or Lamborghini’s Muira, but precious few others.

This wasn’t a race car converted for the road, which would have been an obvious and cost-effective way to get the Veyron to its speed targets. There wasn’t even any recent racing heritage to speak of, unless you want to flick your calendar back past World War II.

Moving on from the short-lived EB110 developed by an earlier Bugatti car owner and built just outside Modena, Italy, Piech demanded his French-built Veyron was true to the 1999 18/3 Chiron concept car in every visual way. What’s more, he insisted it become a contemporary version of the Bugatti Royale, a car that kings and industrial icons drove themselves, with unmatched speed and luxury.

“The Bugatti Veyron has shown that our engineers are capable of achieving a previously unimagined level of technical excellence, thereby opening up whole new dimensions in the automotive sector,” Durheimer insisted. “With a world record speed of 431.072 km/h, it has become an icon of longitudinal dynamics,” he said.

Whatever Durheimer’s people do next, it will be hard to top the impact the Veyron had on an unsuspecting supercar world that was used to V12s from both Ferrari and Lamborghini – with the occasional upward blip from the likes of the Enzo or Pagani or the not-always-credible Koenigsegg.

The latter still often claims to build a match for the Veyron in every way, even without the budget Bugatti’s engineering leader Dr Wolfgang Schreiber had for the Veyron. The budget was, effectively, no budget. It was an exercise in getting it done and counting it up later, which was a very non-Piech way to do business.

One of the biggest reasons they were losing so much money was that the research and development team, tasked with perfection, found that the law of diminishing returns bit them hard at the outer edges of what is possible.

The law bit them especially hard when they had to stick so religiously to the concept car’s visuals. It became so problematic that the production car was released two full years after the first prototypes were on the road.

There was no real budget for the Veyron because Schreiber only arrived late in the program, after new Volkswagen Group boss Bernd Pischetsrieder and new Bugatti president, Dr Thomas Bscher, went through the car with a fine-toothed comb and realised it was in trouble. Effectively, they started again.

With a drag coefficient of 0.41 (or 0.36 with the top-speed wing setting), it didn’t so much slice through the air as barge its way through – you need a lot of power to move that much air.

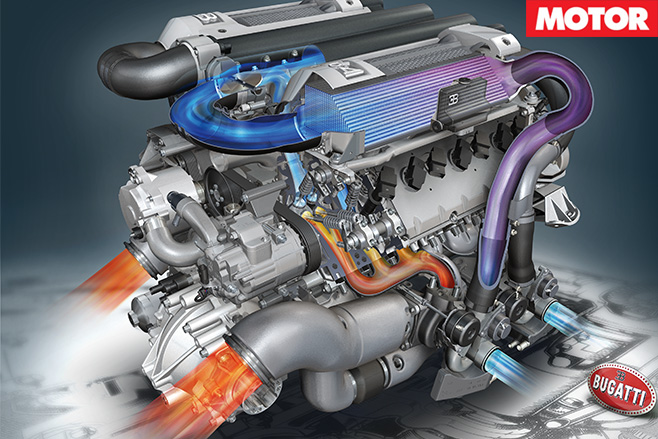

Cooling it was also a bit tricky. The Veyron had 10 radiators. Yep, 10. It boasted three radiators for the engine, three more heat exchangers for the air-to-liquid intercoolers and even more for the transmission oil, the differential oil, the engine oil and one last one for the air conditioner.

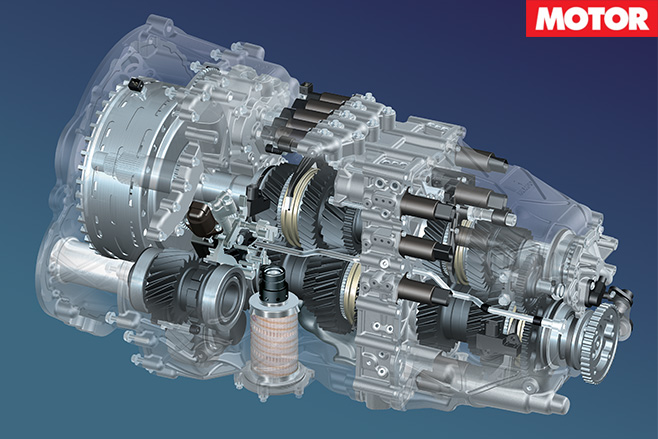

It used the best Haldex-derived centre diff system available at the time and tortured it. Then it strained the seven-speed dual-clutch transmission so much that its production didn’t go to BorgWarner, GETRAG or ZF, like most German sports cars (and most of the Volkswagen Group) did. It went to British racing specialist, Ricardo.

Even with its introductory power output, the car still managed to smash beyond 100km/h in 2.5 seconds, beyond 200km/h in seven seconds and past 300km/h in 15 seconds. It kept going (after you’d stopped and inserted its go-crazy key to reduce drag and lower the downforce to just 100kg at the rear) to a top speed limited at 407km/h – a number less arbitrary than most knew.

Unlimited, the 882kW Veyron Super Sport broke (and still holds) the production car speed record at 431.072km/h, though it pulled 434km/h on the fastest of the two averaged official runs – and all with a Volkswagen Group warranty.

The thing about the Veyron’s power output, though, wasn’t that it had 736kW when it launched. It had a minimum of 736kW, regardless of altitude or temperature. The real number was closer to 775kW, Schreiber admitted.

Its extremes of speed and acceleration made people rethink everything they knew about fast cars. Other cars claimed very high top speeds, but the Volkswagen Group validated everything it did in pure engineering terms, and then some. The last thing they wanted was somebody dying in one due to a mechanical failure at v-max.

They had to come up with some ludicrously expensive solutions, like finding a metal for the horseshoe grille that would bend at speed and then bend back again once the stress was over. It went to extremes like connecting the ABS to the handbrake as well as the massive carbon-ceramic grabbing calipers, just in case it had to be used as a back-up. You could brake the Veyron at 0.9g, just on its handbrake.

When the Veyron launched, only a handful of cars were capable of moving at more than 300km/h, and most of those were very low volume and lacked what Volkswagen would have regarded as proper engineering and development and validation testing.

And yet, the Veyron hit 300km/h just 15 seconds after launching off the line. The acceleration – from any speed, in any gear – is what I’ll remember most. I once had a photographer in a Super Sport who insisted on shooting from the passenger footwell on a test track, then told me to stand on the throttle.

It was one of the biggest errors of his career, and he was forced, constantly, into the seat so hard that he couldn’t inhale until the Veyron had pulled fifth gear. It’s the only car I’ve ever driven where, in a straight sprint with a Hayabusa, I had to repeatedly lift off the throttle to avoid getting too close to the bike.

I also remember the car’s composure. The gearbox was the fastest shifter around at the time – in around 150 milliseconds – and it was silky smooth. The thing sounded like an offshore powerboat and it had torque everywhere, always accompanied by that enormous swoosh of turbo-rammed air that sounded like a hot-air balloon punching out more flame.

And it handled. Not light-of-touch, like a Cayman S, but up to about eight-tenths, it walked around a bit and had a lot of the 911’s manners. It got a little dull as you pushed it to its limits and the weight took over, but it was foolproof, as long as you adjusted your braking points to the new layer of speed it was forever sneaking up to.

In its final fling, the La Finale closed the Veyron story where it began, in Geneva, though its 882kW peak power had grown by 147kW since the car’s launch. It also had an astonishing 1500Nm of torque.

Veyron owners were initially required to change their custom-made run-flat Michelins every 5000km (it eventually moved out to 10,000km) whether there was tread left or not. This was because of the stresses on the belts at v-max. A set cost $22,000.

Bugatti’s concern (and this is the engineering-driven attitude) was that because it had a 407km/h v-max, they had to assume the car was going to be driven at that speed. It was a legitimate fear because at 407km/h, the rear tyres, Michelin admitted, would fail after 15 minutes with that sort of heat and centrifugal force.

That never happened, in part because the Veyron could only carry enough fuel for 12 minutes at its top speed. Delivering peak power drained the Veyron’s tank at five litres a minute.

What made the compulsory tyre change worse was that the only equipment capable of removing the tyres, and precisely matching their successors, was in France. So, Veyrons had to be shipped there to have their new boots fitted at a cost of $91,000. Plus shipping.

The brilliant Ricardo-built dual-clutch transmission cost around $160,000, or twice what the most-expensive Volkswagen-branded car cost at the time. “In the Veyron, Bugatti has created an automobile icon and established itself as the world’s most exclusive supercar brand,” Bugatti Automobiles President, Wolfgang Dürheimer said.

“So far, no other carmaker has managed to successfully market a product that stands for unique top-class technical performance and pure luxury in a comparable price/volume range. An unprecedented chapter in automobile history has reached its climax.” That is not an exaggeration.

Bugatti Veyron Super Sport

Body: 2-door, 2-seat coupe Drive: all-wheel Engine: 7993cc W16, DOHC, 64v Bore/stroke: 86.0 x 86.0mm Compression: 8.3:1 Power: 882kW @ 6400rpm Torque: 1500Nm @ 3000-5000rpm Power/weight: 480kW/tonne 0-100km/h: 2.5sec (claimed) Transmission: 7-speed DSG Weight: 1838kg Suspension: A-arms, coil springs, double wishbone, anti-roll bar (f/r) L/W/H: 4462/1998/1190mm Wheelbase: 2710mm Tracks: 1715/1618mm (f/r) Steering: hydraulically-assisted rack-and-pinion Brakes: 400mm ventilated discs, 8-piston calipers (f); 380mm ventilated discs, 6-piston calipers (r) Wheels: 20 x 11.0-inch (f); 21 x 14.0-inch (r) Tyres: 265/680 ZR500A 99Y (f); 365/710 ZR540A 108Y (r); Michelin Pilot Sports Price: ¤2.3 million (approx.) AUD$3.16 million (with Aussie taxes that’s more like $5.1m…) Positives: Brain-frying speed; polished dynamics; technological prowess Negatives: Hilarious price tag; heart attack-inducing maintenance costs

5 out of 5 stars