An inside look at the man, the fear, the Bluebird and the lake.

First published in the April 1981 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

TUCKED AWAY in a wardrobe, among a collection of old rally jackets, flameproof driving suits and out-of-fashion television blazers, is a tie I’ve never worn.

lt is slim, and dark blue. It is marked with four white stars arranged in the formation of the Southern Cross, above a bluebird in flight. Below the bird hangs a series of miniature maps of Australia, each outlined in gold.

Within each outline is one of two numbers: first 403.1, then 276.3.

The tie has the shiny look of silk, although a tag at the back carries the admission of being 100 percent polyester fibre. But very discreetly. That was typical of the presenter. To him, appearances were all important.

The suggestion always had to be made that the finest of anything was involved – whether it be materials, people or resolve. If you pressed for facts, and turned things around, you could usually find the truth. Around himself, he built a wall – a facade of images – that represented the man he wanted the world to know.

And yet, deliberately, he left chinks in the wall through which you could peer to observe the real person, flawed and devious and covered in the warts of self-doubt. Straining to be a hero, he was anxious to be found out.

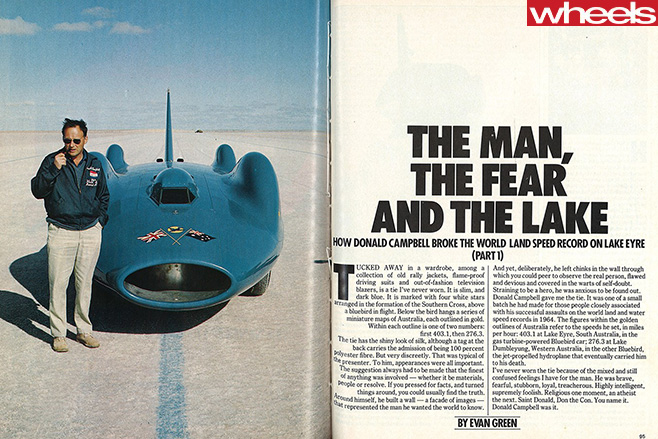

Donald Campbell gave me the tie. It was one of a small batch he had made for those people closely associated with his successful assaults on the world land and water speed records in 1964. The figures within the golden outlines of Australia refer to the speeds he set, in miles per hour: 403.1 at Lake Eyre, South Australia, in the gas turbine-powered Bluebird car; 276.3 at Lake Dumbleyung, Western Australia, in the other Bluebird, the jet-propelled hydroplane that eventually carried him to his death.

He first came to Australia in 1963 to try to break John Cobb’s 1947 land speed record of 394.196mph (634.379km/h) for the flying mile. Trailing an entourage of technical assistants, journalists and film makers, he headed for Lake Eyre. It was a doomed venture, made pathetic by some of the publicity which Campbell himself had helped unleash, and by happenings over which he had no control.

To start with, Lake Eyre was an extremely risky location. No one knew much about the place. It was known that it was the largest salt lake in Australia, that it was usually dry, that the lowest point was below sea level and that the natives were friendly. On the strength of that information, the Bluebird circus came to Australia.

Once before, the giant car had run in quest of the record. Campbell had taken Bluebird to the USA, to the famous salt flats of Utah, where his illustrious father, Sir Malcolm Campbell, had set world records before the war. And at Utah, Donald had nearly killed himself.

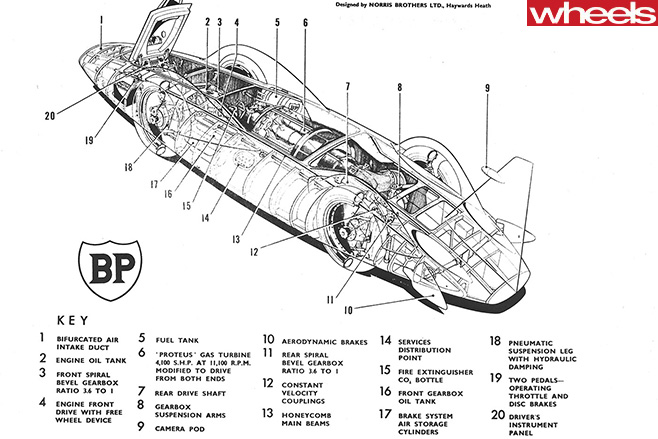

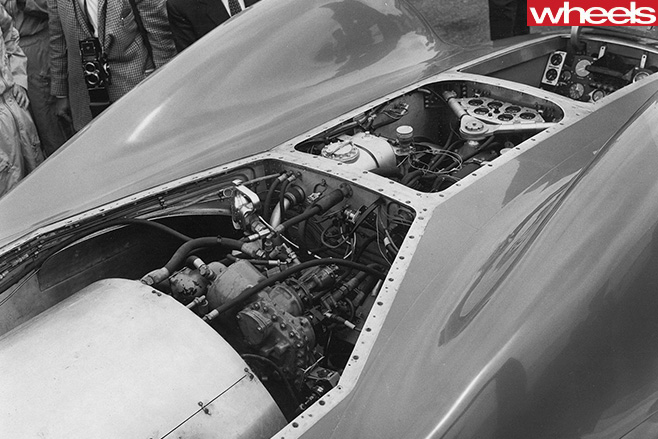

The Utah strip is short and, in trying to gain speed rapidly, Campbell had accelerated too hard too soon. The four big wheels, all driven by the Proteus gas turbine, began spinning on the salt, one side began to lift and, in an instant, the accelerating projectile was out of control. It began to cartwheel through the air.

Alternately spinning through the air and gouging salt, it tore along the marked line, shedding wheels and mangling bodywork as Campbell rode out the fastest car accident any man had experienced. Finally, the remains of the blue shell stopped, belly down on the track.

The driver – incredibly – turned off all the switches bar one and lapsed into unconsciousness. His skull was fractured and one ear torn off. The one switch he had missed controlled the fuel supply to the engine, still running at full power.

The accident almost claimed the life of Campbell’s chief mechanic, Swiss-born Leo Villa. Old Leo – who had endured the autocratic Sir Malcolm, first as riding mechanic then as chief preparer of his record breakers – was devoted to Donald and raced to his aid. From a distance, the wreckage looked like some gaseous nightmare, with exhaust fumes distorting the image, the Bluebird’s shell dancing with vibration and the echoes of the turbine’s shriek bouncing back from the mountains that rim the salt flats. Close up, Leo saw Campbell still in the cockpit and painted the bright crimson of arterial blood. He dashed to the nose of the car to unlatch the cockpit cover. He stood in front of the air intake, and, like a scrap of paper near a vacuum cleaner nozzle, he was sucked in.

The Bluebird had a divided air intake, with passages running either side of the driver’s compartment. Villa went in legs first. Luckily for him, one leg went up each passageway. He came to a sharp and agonising halt on the divider and passed out. Another helper turned off the turbine and pulled him out.

The lesson from Utah – apart from Villa’s resolve never again to stand in front of the thing when it was running – was that a much longer strip was needed to allow the Bluebird to reach its maximum speed without having to accelerate so hard that wheelspin could occur. The minimum distance to reach the required speed in safety, and stop again, was 32km. So they came to Lake Eyre.

Before Campbell’s arrival, a motorcyclist had tried to set speed records on the southern fringe of Lake Eyre and nearly skinned himself when he fell off. Otherwise, it was a virgin lake – not only for speed attempts of the magnitude Campbell was contemplating, but for almost anything else.

The aborigines had shunned the area, weaving legends about demons that devoured people who strayed too close to its shores. Like many myths, the stories probably evolved from fact. The edges of the lake are treacherous, and capable of swallowing a person. Near the shoreline, a thin crust of salt covers a deep mire of mud – a gypsum slush that is a vile black substance like axle grease. Break through that salt and you would go down in the mud like an animal in quicksand.

Getting the Bluebird and all its supporting equipment on Lake Eyre required the construction of a long causeway, to bridge the thinnest salt. On the lake, a safe route had to be charted through the dangerous shoals of shallow crust. Then a course for the record attempt had to be found, surveyed, graded and marked. Camps had to be established, water stored, food brought in, airstrips graded, communication links formed.

Campbell had persuaded many of the most important companies in Britain to back the venture. Many people felt such a massive, semi-national enterprise was against the spirit of record breaking. They preferred the give-it-a-go mentality, which had sent so many earlier exponents to their graves, amid waves of adulation. Trying and dying was what it was all about, not spending big and waiting for everything to be right. Campbell was urged to get it over. But he waited.

The early columns of praise soon turned into sarcastic paragraphs. Most couldn’t understand the complexity of record breaking: the fact that a ripple in the salt or four knots of wind from the side could send the car plunging out of control; the fact that the team was exploring unknown realms in terms of tyre grip and wind resistance; and, above all, they couldn’t understand Donald Campbell. If the world’s press expected a devil-may-care adventurer, that was the role he would play. But it was false, and it was trying to live up to this false image that caused so many problems. He was, at heart, a technician, fascinated by the challenge of overcoming the physical problems of travelling at more than 640km/h (400mph) on land, and he wanted to take each step in meeting that challenge carefully, logically, knowingly, as he and the team tuned the car for the ultimate run and the record.

He was in no hurry. He had the mind of a test pilot, the patience of a chess player.

Not legal, said Campbell, in his most understated British voice. The FIA rules stated that a record breaker had to be driven by its own wheels. That distinction was beyond most people. It’s all record breaking, isn’t it? What’s wrong with the bloke? ls he scared or something?

Stiff upper lip, but still there was no record run. The track was too soft. The wind too strong. The engine needed test runs. The braking system had to be recalibrated. The parachute tested. Tyre temperatures checked.

Don the Dingo, they called him. For Christ’s sake why doesn’t he just get in the bloody thing and give it a go? And then it rained, and they all went home.

Not all of the project’s backers were prepared to continue with what they now regarded as something of a lost cause, if not a charade, which was even worse for those bastions of British industry.

Campbell, however, was determined to keep trying for the record. He lost his main financial backer, BP, but managed to persuade the Australian oil company Ampol to assume the role of principal sponsor. That was how I became involved.

Among those who had defected from the Campbell cause was the man who ran the show in 1963, the Britisher David Wynn Morgan. Campbell, therefore, had no project manager and asked Ampol to nominate someone. I had worked for the company some years earlier as one of its PR executives and, among other things, had directed the 1958 Ampol Trial. Dick Mason, one of my mates at Ampol, had risen to the rank of General Manager, and asked if I would manage the attempt.

Mason, Campbell, and I had dinner in Sydney the night after Campbell arrived in Australia. Campbell was both a superb salesman and a gifted actor. He needed someone to untangle the mess of ’63 and went to work on me with great skill. He was conservatively dressed (in blue of course; he had a fetish about the colour) and modest to the point that words had to be dragged from him but when that point was reached, he glowed with resolution, and determination to make this a successful British-Australian venture.

No trace of Don the Con. More the Duke of Edinburgh with just a hint of a Graham Hill waiting to be turned loose.

“I’m just the driver,” he told me, fixing me with his bright, intense eyes. “You run the show. You tell me what to do.”

Very heady stuff for a bloke who’d been raised on books about Segrave, Campbell and Cobb. Dick Mason took me to one side. He was a former RN submarine commander who had drifted into the commercial world and revealed sparkling talent. Forthright and honest. A friend.

“You know what they said about him last year,” he said. “This is not going to be easy, but please do it. And please, get him to break the bloody record quickly.’”

To my horror, I found the revamped record attempt was already a Big Deal. The show I was supposed to be running was already underway – and largely out of control. Campbell, who never bothered with the correct target if he could aim higher, had enlisted the aid of Prime Minister Menzies, and been given the army and air force. More than 100 soldiers were encamped near the homestead. They were to provide transport to haul Bluebird and its equipment, and to police the lake. The RAAF provided a doctor and an aerial ambulance.

Leo Villa and two assistant were there, already preparing the car for its first run. Then there were the remnants of the supporters who had supplied the project with critical components and the experts to make them work: things like the gas turbine, instrumentation, suspension and brakes. There was a refuelling squad from Ampol, good blokes who were vastly distrusted by the Brits who had a hankering for BP. There was the track squad, a large group of deeply tanned men, who wore shorts and puzzled looks at my presence; they had been working on the salt for weeks, grading and measuring a track that ran the full 32km

A DCA official had established an air traffic control at the station’s landing strip, and a PMG man had installed a post office and radio telephone link with the south. A few dozen visitors had camped on the balks of the Frome River, where bore water had formed a deep swimming hole; they’d come for a few days, to see Campbell break the record. The dozen or more people who lived at Muloorina were there of course, bearing their confusion with great dignity. A film crew had arrived and were complaining of the dust. And there were journalists from various newspapers, networks and agencies. Not as many as in 1963, they came armour-plated with cynicism. Too many had come too soon.

Ken Norris was shocked. “We can’t run for weeks,” he said. ”Donald must be given the chance to test the car. We need lots of runs, each at progressive speeds. I don’t know how the machine is going to behave at the sort of velocities we’re aiming at. lf the attitude is out by half a degree – you know, if the nose is too high and the tail too low – we could kill him.”

The army chief, Colonel Clif Brebner, expressed an opposite sentiment. “Welcome,” he began, “and I hope you’re better than that bastard who was here last time. And try and get things over quickly. We can’t stay long. We’ve justified this exercise on the basis of gaining outback experience but the men can only stay a couple of weeks.”

The technical team – all meticulous men, specialists in their own field and jealous of their companies’ reputations – wanted time to do the job properly. The journalists were already impatient. A Sydney writer who had been there before, buttonholed me. “Are you gonna make him have a go, or is he gonna fart-arse around like last year?”

The team who had been preparing the track greeted me with the warmth that a pit full of cobras might extend to a mongoose flung in their midst. They had reason. Their leader, Andrew Mustard, assumed he was in charge of the whole project. He had been Dunlop’s representative in 1963 and was now a private contractor, looking after the tyres and the track. Campbell had told him nothing about me. To make the situation worse, Campbell wasn’t at Lake Eyre. He had assured me he would be there, but there was a message that he was spending a few days with friends in Adelaide.

So here was Andrew Mustard – who had spent weeks with his men on the salt, working in the sort of reflected heat that few people could imagine let alone tolerate, and sustaining himself with the thought that he would be running the show – out on his ear, or, at least, reduced to a lesser role, by a stranger.

That first night was busy. There was a meeting of all parties. I explained my role, and heard reports from the various teams.

I held a press conference in the Army canteen to outline our program for the next few days and then collared the PMG man who opened the telephone link so that I could ring a contact in Adelaide.

“Tell Donald he must be here tomorrow,” I said. He came two days later and we had our first argument.

“But Unk (Leo Villa) said there was no need to come,” he said. (I was to learn that Leo, who loved ‘the governor’ dearly, was inclined to treat Donald like a son, and tell him what he wanted to hear.)

“You’ve got a couple of hundred people sitting up here, waiting to see if you’re fair dinkum or not. The worst thing you could do is stay in Adelaide.”

“But what can I do up here? I’m not needed yet. You run the show.”

“You are the show. And you’ve got to prove yourself to these people.”

He was shocked and said nothing for a few moments. But then the words began to flow he called me “old boy” a couple of times, and he agreed to stay at Muloorina. For several days, he turned on a magnificent PR show, meeting all the groups, placating Andrew Mustard and his team, and immersing himself in the preparation of the car.

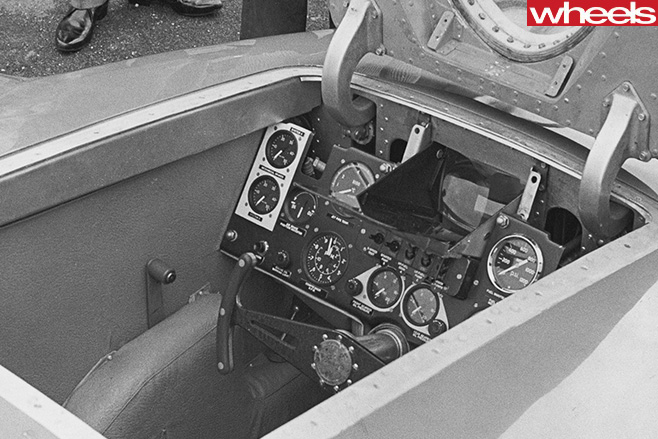

A base camp was established on the lake near the marked tract. The first cautious runs were held, and Campbell displayed his remarkable memory and grasp of detail. The course had different markers at each mile for the full 20 miles (32km) and, after each run, he could recall the readings on each Instrument at each mile mark, as well as comment on the feel of the car. He had phenomenal powers of concentration and recollection.

Then dinner, followed by a formal press briefing, usually in the shearing shed. Afterwards, we would talk to the film crew, to discuss their needs. Last thing of all, I would chat with Colonel Brebner about security arrangements for the next day. We had to guard against a dazzling variety of possibilities. They ranged from campers sneaking on to the lake at night (and either getting lost or being run over by a long blue car whose driver had limited forward vision) to pilots who flew to the lake before dawn. Some of the visiting flyers did horrifying things. Mostly graziers from western New South Wales or Queensland, they would arrive over the salt at five o’clock in the morning, and circle above the headlights of our vehicles waiting for the sun to reveal a landing place. Oblivious to each other, they would drone above the lights on the lake like moths around candles.

There were boggy spots on the lake to avoid, fresh tracks to mark, signs to be erected and rescue procedures to be planned. The risk of becoming lost on the lake was real, for, on a bright day, heat haze reduced visibility to 400 metres.

I enjoyed those late night talks with Clif Brebner. Apart from being a Colonel, he was also a senior officer in the SA police force. He was a man who had seen the hard side of life, and I think my innocence amused him. We had long talks, and he became my closest friend at the camp. Normally firm but quiet, he could be stirred into action, and when provoked, he was marvellous to behold.

Some CAMS stewards arrived, and the camp erupted in controversy. They came with the understanding that someone other than I was running the project, and refused to deal with me. They issued Campbell with an ultimatum: he had to prove to them that he was fit to drive the car. The question of a spinal injury was raised (Campbell had been run over by a truck during the war) and even the question of his mental balance was raised!

Campbell erupted. The press corps was delighted, for here were stories at last and good, rich Campbellesque controversy. Clif Brebner grew progressively less amused. One night, while discussing the latest madness, he exploded.

‘”I think it’s time I straightened these bastards out,” he hissed, and marched into the tent where the stewards slept.

“All right, gentlemen,” he bellowed. “Sit up and shut up.”

All around the tent, startled faces appeared from the sea of army blankets. The Colonel began modestly enough, reminding them that their duty was to observe and control, not to connive and ruin. When someone attempted to speak, he blasted him into silence. Then, warming, he stung them with barbs poisoned with clichés about petty dictators and the eyes of the world being on them. He reminded them that there was government interest in the venture succeeding, not in being hamstrung by stupidity.

Thoroughly aroused, he reminded them that he was in the police force, asked them if they ever ventured by car into Adelaide (the heads nodded) and he smiled wickedly. There was always, he said, the vague possibility of harassment, and his eyes suggested everything from arrest to castration. Then he stormed out of the tent.

Out of hearing range, he turned to me and burst into laughter. “I don’t know whether that did any good or not,” he said, “but I feel a hell of a lot better.”

A few days later, the stewards went home, to be replaced by a more experienced group.

It cost him $2000 a month in hiring charges, plus flying time, and he had engaged a former airline pilot to help him gain certification for the aircraft.

lt soon became clear that Campbell had strong, and very different feelings about fast travel on air, water and land.

His great love was flying. His happiest moments were at the controls of the Aero Commander, and he would search for excuses to fly: off to Leigh Creek for supplies, to the east to see the Birdsville Track, down to Adelaide for dinner.

The aircraft came first, the boat second. The Bluebird hydroplane, in which he had already set the world water speed record, was regarded with affection. He knew it was dangerous, but he liked it. He talked of the boat with a mixture of pride and amused tolerance, like a father discussing a naughty but gifted child. He would forgive it anything. Even killing him.

But the car he hated. It frightened him, although he never allowed fear to stop him driving it, for he was the bravest man I knew. He was also intensely superstitious and worried about the legends of Lake Eyre. Each night before a scheduled run, he would play a gypsy game of cards and study them for any signs of doom on the morrow … and keep on turning up cards until some awful prospect was revealed. Thus chilled, he would go to bed, his face gaunt with distress.

Yet he was chained to the Bluebird by a complex series of links. One was his intense patriotism. He would die rather than Let The Side Down. British was best; that was the real thing to him and he was committed to proving it. Another link was that he had failed twice and, whatever he was, he was no quitter. And there was the fact that he was the son of Sir Malcolm.

I got close to Campbell in those early weeks and there was no doubt in my mind that he feared his father, even though the old man had been dead for years. There were many things to remind him of Sir Malcolm. Old Leo, who had worked with the father through the great years. The Bluebird, the same name his father had chosen. And people kept referring to him as Sir Malcolm.

The son had gained the world water speed records, a supremely hazardous undertaking which should have demonstrated his bravery and competence to the world. But his father was renowned for his feats on the land, and something from the past dragged him in the wake of the old man’s achievements.

Sir Malcolm had been a public hero to an Empire on which the sun never set but, as sometimes happens with such men, behaved shockingly to his family. A heavy drinker and womaniser, he required impossible standards from his son.

On days when the Bluebird was not running, Donald and l would walk through the sand dunes near Muloorina, to get his mind off the lake and the car and the worries of being heir to the world’s most famous record breaker. He was a keen collector of guns and, sometimes, we took samples from his collection to shoot at targets in the sand. Occasionally, we would roam the hills with Elliot Price, and that marvellous old character – looking like a rotund version of Edward G. Robinson – would talk about his days in the bush. Mostly we would travel alone. Fretting at the delays, Donald would walk, hands thrust deep in his pockets, head tilted forward, kicking gibbers and bemoaning his fate.

“This wretched place.” A stone would be aimed at some imaginary goal. His eyes, sad as a mournful hound’s and deep set with misery, would lift momentarily. “I am destined to fail.”

Donald laughed ruefully as he recalled such things. The stories were told softly, with an edge of guilt, in the manner of a child confessing to a friend something he did not wish to be overheard by a nearby parent. It was as though Sir Malcolm hovered in Donald’s sub-conscious ready to grab him by the throat if he didn’t do what was expected of him.

Rain fell one night. The Muloorina folk were delighted, because drought had withered the land, but an early morning visit to the lake brought dismay. The track, which had taken months to construct, mark and measure, was discovered to be in the lowest part of the vast basin. Therefore, the solitary pool of water, which remained from the rain, sprawled across the centre of the 32km strip. Then winds came, to tantalise us. A gust would whisk the water from the track, raising our hopes that the salt might dry quickly. And then another gust would send it scudding back, in a wide, shallow sheet of ruffled blue, to saturate the strip even more. It would take months to dry.

Most of the soldiers left. The air force flew off to Woomera. The press packed up, leaving just a few agency men. And we began all over again. A new, firm course had to be surveyed and constructed in a few weeks. The car could run only during the milder months around winter, before rising temperatures thinned the air and turned the lake’s surface into a scorching hot-plate that would blister the paper-thin treads on the tyres.

Despite its enormous area, only a small part of the lake had salt that was thick enough to support the car. The sedimentary layer – washed down by floods and the mineral residue of rain – was deepest in the lowest part of the basin. And that, naturally, was where the water now lay. Thus were we compelled to seek a new course in the region of damp patches and that windswept puddle.

We drew a map of the lower lake area, coded zones, and marked certain reference points. Known lagoons and wet spots were drawn in. To search from ground level would have been too slow, because the ring of heat haze that encircled a person on the salt limited visibility to a frustratingly short range. The true horizon was clear only at dawn. Thereafter, the edges of the lake seemed to rise in shimmering layers and curl inwards, as though the world around you were buckling and vaporising under the heat of the climbing sun.

So we used the Aero Commander. Donald would take the plane high above the lake and look for a line that seemed clear of water and the dark blotches that meant black mud was close to the surface. Then he would fly low, and set a course that we on the ground could follow in our cars. We would mark the way with barrels and stakes and, if the line seemed promising, would return slowly, drilling the salt at regular intervals to test its thickness. Usually, there were thin patches to ruin our hopes.

Following one line, I drove into a region of wafer-thin salt. The tyres began to sink. I tried to drive out, taking the Valiant in a wide curve while, all around the surface rippled and cracked, like an ice floe shattering. The wheel tracks turned from indentations in the white salt to deep channels in the grease-like mud, until finally, surrounded by shattered plates of salt crust and oozing springs of gypsum slush, the car became hopelessly bogged.

I had to abandon the vehicle for the night. When I returned next day, with rolls of chain wire (and AAP reporter Wally Parr who –

incredibly – had volunteered to help) the car had sunk on one side. The broken salt reached to the bottom of the doors. In a few days, the car might have disappeared altogether. Wally and I worked for 10 hours to extricate the car. Salt crystals like the fragments of a broken windscreen sliced our hands, so we finished the day bloodied and muddied. But we got the car out and, within a few days, had found a stretch of firm, dry salt.

More showers fell, and the firm portion of the new track was reduced to 18.2km.

Not safe, said Norris. We must try, said Donald Campbell.

It was his decision to make, and it was a brave one, but he grew restless and more melancholy as each day passed. Some days, he would spend hours watching the track preparation team at work. The grader would shave knobs and shallow craters from the selected strip while the follow-up trucks, trailing lengths of steel rail, would polish the graded surface.

And some days, while all the team was conducting an ‘emu bob’ – a slow walk down the entire track, picking up loose knobs of salt, stamping soft spots underfoot – Campbell would fly to Adelaide to have dinner with friends and the weary workers would spend the night growling with discontent.

Those common plagues of the outback, boredom and lethargy, settled on the camp. A routine of 4am starts, dawn winds and aborted runs eroded patience and spread discontent. Reasonable people became snarling extremists. Systems were forgotten and drivers heading across the lake from the base camp to the causeway – a 30 minute journey across a white wilderness – grew careless and became lost in the floating mirages. Others wasted time looking for them.

Men frozen at dawn were burned black at midday. Lips were cracked and refused to heal. Faces set in leathery masks, creased by the wrinkles of perpetual squints. The arrival of two young female cooks, to help at the homestead, made things worse. The girls grew better looking by the day. Instincts were aroused, and, with a male-to-female ratio of around 80 to one, a few noses were threatened with a thumping. Some distractions were needed.

First, we organised a game of cricket, certainly the first ever held on Lake Eyre and, for one day, people laughed at the difficulty of hitting a boundary that was 290km to the north.

Strong winds blew every morning, and the Bluebird, its tall tail fin peeking from the vehicle’s blue cover, sat on the salt. So we had a regatta. For land yachts, of course, and the reason for such an event was twofold.

First, building the wheeled vehicles (from the purloined wheels of Elliot Price’s wheelbarrows and welding trolleys, with sails cut from Dunlop banners) gave essentially mechanical minds some welcome exercise.

Second, if we needed wind (as the yachts would) the weather was certain to become calm. Inspired by such Irish logic, a flotilla of two yachts took to the salt for Lake Eyre’s first regatta. Within three days, the winds dropped. The Bluebird roared into life again.

The first speed runs scarred the surface and left ice-blue ruts of watery salt. A few days of sunshine and the ruts hardened, set in the salt like glossy tramlines on a white road.

“We need time,” Ken Norris said as we walked down the tramlines. “There is still much to do. The track is too short. Donald will have to accelerate more rapidly than we’ve been planning and we just have to find out how the car behaves under these new conditions.” He looked at me with deep concern. “And look at those ruts. This place is so bloody dangerous.”

More than ever, the project needed understanding but the mood among most of the watchers was one of hostility. The technical reasons for not trying for the record in one make-or-break attempt were lost on people who could drive a truck across the ungraded salt flat out. The discontent grew into storms that flashed through the camp at night.

We needed an ally: someone expert enough and respected enough to silence the howls of derision. Someone who knew what he was talking about, and could say: “This is difficult and dangerous and Campbell knows what he’s doing. Give him a fair go.”

So Lex Davison came to Muloorina. A man of exquisite manners, he had sent a message saying he would like to bring his wife and family to see the Bluebird but didn’t want to barge in at a difficult time.

I explained who he was to Donald Campbell and Ken Norris.

“He’s a great racing driver, a gentleman, and highly respected,” I said.

Donald nodded. “He’s a nice bloke and if he’s on side, it would certainly help you.” Another nod.

“Would you allow Lex to drive Bluebird?”

Campbell looked shocked. “What? And go for the record!”

“Of course not. But if you were to let him drive the car, at whatever speed you like, and Ken explains what we’re trying to do, you’ll have made a friend that other people will listen to.”

So Lex Davison came to Lake Eyre, and drove the Bluebird. He listened intently to Ken Norris, spent hours with Leo Villa and the various component experts, and studied the whole project with deep interest. He was impressed by the sophistication of the car, the complexity of the project and the enormity of the risk to the driver. And he said so, to the journalists who followed him and to anyone else who would listen. The visit had a remarkable effect.

Campbell slipped back into the role of record breaker. He became enthusiastic again and – as though to justify the faith Lex Davison had shown in him – resolved to go for the record as soon as possible. No more sneaking off to Adelaide to get away from the miseries of Muloorina. He stayed at the lake, and seemed supercharged with resolution.

The Davison visit and the unaccustomed wave of public sympathy also had an effect on other members of the team. Instead of criticising the driver for the delays, they turned their attention to the track. The more the strip was graded, the softer and damper it seemed to become. More runs produced more ruts.

“This is madness,” Ken Norris warned.

“The maddest thing is what’s being done to the track,” said Lofty Taylor, the gangling leader of the refuelling team. Lofty worked for Ampol, and I’d known him since the Ampol Trial days. l had enormous respect for his opinion. He was practical, versatile, prepared to move mountains if asked and yet able to detect the faintest whiff of cant at long distance.

He admitted he knew nothing about grading salt but pointed out that neither did anyone else, for the science of building record tracks on salt lakes was in its infancy. And he reckoned he knew as much about it as anyone else.

“They’ve been cutting salt off the top all the time,” he said. “All that grading and cutting is weakening it, and bringing moisture to the top.”

“What would you do, Lofty?”

“Leave it alone for a while. Let the crust heal and harden.”

The track squad was ruffled. The problem, they said, was due to the constant interruptions to their work. They couldn’t get the surface right with the car running every other day and cutting grooves in the salt. So runs were suspended. Andrew Mustard’s team would pursue their theories and have a clear week to try to bring the track up to record standard. Donald took some of the crew to Adelaide, for a few days’ break and all seemed calm. In fact, a major storm was brewing.

Mustard had brought an Elfin racing car to the lake. It was fitted with tyres that had scaled-down versions of the tread being used on Bluebird. He drove it to test such things as tread temperature and the coefficient of friction of the salt surface at different times of the day. He usually drove the little single-seater down the strip before Campbell made a test run. On one occasion, he was driving the Elfin up the strip when Campbell was driving the Bluebird down the strip and the world’s highest speed head-on collision was avoided by a whisker, with a sheepish Mustard – spotting the rooster tail of white salt spray bearing down on him – spinning off the track.

One day during the lull, Ken Norris and I went to the lake to see how the track work was progressing. To our astonishment, we found the CAMS timekeepers and stewards assembled at their record posts.

“Andrew’s going for his records,” one of them said, and, seeing our bewilderment, gave us that ‘don’t tell me you don’t know about it look’. It seemed there had been an application made for attempts on various Australian class records for categories suiting the Elfin.

Neither Ken nor I knew anything of it.

Nor, it seemed, did Campbell, and when he returned that night there was an eruption. The track squad was sacked and Lofty Taylor given the job of preparing the strip.

“What do you suggest?” I asked Lofty.

“We should all go away for a couple of weeks and let the salt alone.”

But everyone else was fired up to do something. lt was now June and we had been at Muloorina for six weeks; the track seemed to have hardened, the car was ready and, most important of all, Donald Campbell was anxious to go. He was not looking forward to running, but, in the manner of a person who is required to undergo a major surgical operation, was keen to get it over with.

Through all the weeks of controversy and anxiety, Campbell had been sustained by the strength and sympathetic encouragement of his wife Tonia. She was a remarkable woman. A Belgian singer and top-flight nightclub entertainer is hardly the person one would have cast in the role of a record breaker’s wife, required to endure weeks of crushing monotony, sprinkled with moments when the husband’s life was at risk. Two more opposite characters than Donald Campbell and Tonia Bern would have been hard to imagine, yet she was the perfect partner. Sympathetic. Oozing motherly understanding. And strong as iron.

By nature, she was volatile and moody. At times, she would project Tonia Bern, nightclub star, and sing snatches of a melody or tell outrageous jokes. (A group of graziers, projecting affluence, have flown to Muloorina and are assembled in the loungeroom. Donald is holding court, impressing them with his Duke of Edinburgh manner. ln bursts Tonia. Flashing eyes. A faint swing of the hips.

The hair is tossed, casually, tellingly. The men pop from their lounge chairs. “Oh, down please sit down,” A pirouette. A brief smile at Donald. “Hello darling. I suppose you men have been telling jokes. Have you heard the one about the two French lovers? No? They are on the couch when the phone rings. The man says: ‘You answer that. It’s at your end’.” She stands, eyes wickedly waiting for a response. The men stare at each other. They’re not offended. They don’t understand. She sweeps from the room, a classic exit. A brief wave. The men try to stand but their legs are trembling.

She also performed at Marree, for charity. She was chased out of town. Not by hostile women outraged by her act but by randy men. Understandably, they had not seen a woman like her before. Just as understandably, they didn’t want to let her go. She arrived back at Muloorina, breathless from the chase, and delighted.

At other times, she would withdraw and talk to no-one. She would don her reading glasses and spend hours with needle and thread, poised over some complex tapestry. At the lake, that was how she would spend her time: sewing, while the men fussed over the car, argued over the track, cursed the weather. It was not that she lacked interest in what Campbell did. Just the opposite. She was devoted to him. But she sewed at the lake to forget the car. To her, it was a blue monster that consumed her husband’s interest and threatened to destroy him.

I’m sure she hated the whole business of record breaking, but she went to the lake each day because she wanted to be near her husband. She kept away from him when that was best, spent time with him when that was needed. She mothered him, coaxed him, protected him. Anyone criticising Donald did so at his peril, because Tonia could savage a person with words. lf he were exhausted, she let him sleep and defended the bedroom door like a lioness protecting its lair. She offered support when he needed help, argued when she thought he was wrong, and was loyal no matter what.

Tonia came with me on the morning of the record attempt. She wore a fur coat, because of the cold, and because she could wrap it around her face, and shut out the world. She sat in the back seat of the car as I drove to our position near the middle of the run, not far from the timekeepers’ post. She snuggled in the corner, with only her hair visible. I stood at the front of the car waiting.

lt was a sparkling, chilly dawn. No wind, not a cloud in sight. But so cold that the air stung your nostrils and turned exhaled breath into billowing clouds of fog. The radios buzzed with checks that all was clear. The sun rose and sat on the horizon, like a white wheel ready to run around the perimeter of the Earth.

The mournful howl of the Proteus gas turbine reached us. We couldn’t see the car but the first layers of heat vapour were rising from the end of the track. The level of noise rose. A thrilling sound, that made the scalp tingle. From whine to shriek, it kept growing in intensity. Then, a sound we had never heard before: an angry boom, like a flight of jet planes hurtling across the lake. Still no car. Tonia kept her head buried in the coat.

A high tail of salt spray loomed above the horizon. The noise was dreadful, beyond human endurance and rising. The salt began to vibrate.

And the Bluebird, running hard for the first time at Lake Eyre, burst into view. At first, it looked like a mirage, a gaseous blue shape floating above the rim of the lake; lifting high, inverting, coming back to the track in a series of images and trailing a mixture of burnt air and pulverised salt. I stopped breathing. The car beside me rocked violently, but it was Tonia getting out.

“My god,” she said, and covered her lower face with her hands. The Bluebird, now sharp in focus, was thundering towards us.

I’ve seen many racing cars at speed, and they always look like devices man has made, and is controlling. But that machine looked like something from the past, from an age that man can only imagine. It was some frenzied creature, spitting fire and noise as it hurtled across the bed of a dead lake.

Then he was past, and as the air torn by the Bluebird’s progress came buffeting our way, we resumed breathing, jumped into the car, and drove after the disappearing wake of salt spray.

THE RECORD AT LAST

He was brave, he was foolish but in breaking the world land speed record on Lake Eyre Donald Campbell showed more courage than any man Evan Green has ever known.

The thunder of the gas turbine faded to a hiss as Donald Campbell completed the first run and swung Bluebird in a wide loop, to reach the service point. He drove between the trucks, laden with drums and wheels and batteries, and pointed the car back towards the track.

The service crews moved in. They had practised this routine many times. Change wheels, add fuel, check temperatures. Burrow deep in the blue body to check instruments and examine oil levels. They did their work quietly and quickly, for they knew the car had to make both runs – once in each direction – within 60 minutes to break the record.

A long fuel hose snaked into the side of the body. The wheel covers came off, then the wheels. The car, which only moments before had snorted fire and made the lake tremble with the ferocity of its progress, sat on four spindly jacks, looking like a blue locust that had had the wings and legs plucked from its body.

Donald Campbell sat in the cockpit, canopy closed, head down, as though disappointed. After a while, he lifted the hatch, hauled himself clear, and sat on the car’s nose. There, he waited for someone to bring him walking shoes, as he dared not get salt on the soles of the blue sneakers he used for driving.

Vehicles bearing Leo Villa, Campbell’s chief mechanic, and Ken Norris, the car’s designer, raced across the rough salt, heading for Bluebird. Leo jumped out and raced for the cockpit, his gait stiffened by age. His face was contorted by worry. The track was dangerous and he knew it better than anyone, for he had been in this deadly business longer than anyone. He took several moments to catch his breath.

‘How was that, skipper?’ he asked, and then fired a salvo of questions at the driver, for he wanted to know about the car and the track and how the car had behaved on the soft surface. When agitated, Leo could be difficult to understand. He always spoke rapidly. He coughed and wheezed a great deal too, for he was a chronic smoker. And when he spoke, he fired sentences in a series of bursts that were interrupted only by the desperate need to breathe or cough.

Now he was wound up – for he had lived with the Bluebird project for nine years, and the record was close – and he fired thoughts like a shotgun spitting out pellets. His words kept colliding, as one phrase was overtaken by the next. Campbell put his shoes on, and looked mournful.

Ken Norris waited until Leo Villa paused to wheeze for breath. The two men were opposites, and fascinating to watch when performing beside their creation – the car the English designer had created and the Swiss-born mechanic had lovingly tended. Villa was the volatile continental, Norris the typical British boffin. He was a quiet, shy man, and the greater the crisis, the slower he spoke.

“How was it, Donald?” he asked, polishing each word before letting it escape. “It looked as though it might have been a fast one.”

Leo coughed painfully. Campbell looked at them with sad eyes. “I’d say three-eighty,” he said, in a voice that was slightly more clipped than normal. Nothing more; his heart might have been beating at three times its normal rate, but the voice was controlled. “However I’d say the wheels were breaking through the salt. I could feel it sinking. There was one tricky moment.”

I had been to the radio base, to hear the report from the timekeepers. The speed was 389mph (626km/h). Five short of Cobb’s record. I told the others. Norris did some arithmetic. The car would have to return at 427mph (687km/h) to break the record. John Cobb had done one of his runs at only 378mph (608km/h), so it was certainly possible. Cobb, however, had had a dry track…

Another report came through on the radio. It was from the track squad. The salt had been cut at its softest point, where the new track crossed the old, longer strip which had been flooded by rain. How badly? Deep ruts. They were going to inspect them more closely. From around the car came a hiss of disappointment.

“Well. That’s it,” said Villa. “You can’t go back if it’s like that.”

Norris nodded agreement. “I suppose it depends on just how bad the ruts really are,” he mused, and moved towards the radio, to check on the track report.

“Too dangerous,” said Villa, more to himself but loud enough for all to hear. He headed for the rear of the car, to busy himself in some work.

Campbell looked at me. “This track’s too soft,” he said quietly. “I could feel the car sinking. You know, breaking through and then hauling itself out. It would seem to be holding itself back and then, suddenly surge forward.”

He thrust his hands in his pockets and walked far from the car, kicking salt. “If I go back, we’ll probably lose the whole show. If I don’t go back…”

Campbell looked up. “What should I do? Tell me.”

lt was an impossible question. The decision had to be his, for the life at risk was his. lt was Donald Campbell who was going to be strapped in that cockpit for a 400-plus mph ride over scarred salt. Not me. Not Leo Villa. Not Ken Norris. Donald Campbell, the man staring at me, wanting someone to tell him what he should do.

“We should see for ourselves what the salt’s like,” I said.

“Right,” he said, and began hurrying towards one of the support cars, its grey sides stained with salt. He called to Villa and Norris and we piled into the vehicle.

Campbell drove. Flat out, he took the car over the pimples of salt that lined the edge of the graded track. At the six-mile mark, we stopped and walked to the centre of the strip. There was no doubt where Bluebird had been, for its tracks were as clear as the wheelmarks of a car crossing packed snow. Two ruts tapered to the horizon, weaving slightly, but generally straddling the blue guide line.

He crouched beside them. The ruts were thumbnail-deep. The big wheels had pulverised the salt crust into a soft, damp mush, and in the bright sunlight, the tracks sparkled and winked like grooves in cut glass.

We returned to the car and drove to the measured mile. To our right, strung along the rim of the lake and already shimmering in the morning heat, stood the outlines of tents and trucks and boxes and tripods and men. The timekeepers were waiting…

At the track, the ruts were deeper and blackened by rubber laid by spinning wheels. Even more ominous, the grooves swung wide from the central blue line. Campbell had come through the mile fighting the car and, at a point near the entry to the timed zone, had run perilously close to the rough salt at the edge of the prepared track. To have touched the rough would have meant instant disaster.

“Bloody hell,” said Ken Norris, his words measured with awe.

Campbell ground a heel into the salt, and the depression filled with water.

“How much more power can you give me, Ken?” he asked.

Norris crinkled his brow. “Five percent.”

Leo wheezed in distress. Campbell and Norris walked along the ruts. I was concerned about the time. “The one thing you can’t do is run out of time without making a decision. Let’s get back to the Bluebird and decide what to do there.” The two men nodded and walked back, occasionally bobbing down to inspect a deeper depression, or to glance back along the track.

So we drove back. The Bluebird was ready; wheels on, cables and hoses removed from its body. Ready for glory or failure. Or the humiliation of not running. Villa and Norris scurried towards the car. Campbell and I were alone.

“Well old son,” he said to me, “what’s it to be?” A long pause.

“Do you have a choice?” He looked at me keenly. Slowly, he began to smile, and he nodded, like someone hearing the news that he is dying, from a doctor who can’t find the words to tell him. He winked at me, took a slow breath, and walked towards Bluebird.

“Five percent more power, Ken,” he called. “We’re going.”

A flash of excitement charged the base. People began running. The message that the car would be coming back in a few minutes was relayed to the timeskeepers and other officials strung along the track.

“What is happening, Evan?” Tonia came towards me. I’d forgotten to tell her.

“He’s going to try.”

“Oh my God.” She had been listening to the conversations, and knew the danger. She went to the Bluebird, made sure her husband had Mr Whoppit (the Teddy Bear mascot that accompanied him on all his runs) took his walking shoes, and went back to the car. There, she pulled the collar of her coat around her ears, as the booster motor whined to stir the 4100 shaft horsepower (3057kW) turbine into flaming life.

Campbell was magnificent at that moment.

Those of us who had seen the salt knew the run would almost certainly fail. There were soft patches to negotiate, ruts to avoid, more power to control and a minimum speed of 427mph to reach. But to have quit, even though the dangers were extreme and the chances of success low, would have caused the whole project to crumble.

This was not just an attempt at the world land speed record. This was justification of Donald Campbell. Quitter or trier? The world would judge him on whether he went back for a second run.

He knew it, and he sat in the cockpit of the giant machine he hated, calmly going through his cockpit drill, checking that the timekeepers were ready, hearing that the track was clear, and aiming the car’s gaping nose at the mirages dancing on the horizon. And beyond that horizon, hidden in the rising heat vapours, lay a region of salt that could kill him.

He drove the car impeccably, and harder than was safe, but the run was doomed. At 360mph (579km/h), he hit a soft patch and the Bluebird began to veer out of control. He had to slow as he fought it back on line. Then he applied power again. But the car had lost too much momentum, and, although he flashed through the measured mile with the turbine screaming its hideous song and the wheels spraying fountains of salt high in the air, the chance was gone. John Cobb still held the record.

Days passed while the track healed.

At Muloorina, Campbell talked of many things.

Good things, like building a new car. Ken Norris proposed that it should run on rollers, so that it could go for the world land speed record on water. “You’d start off on land, and have to hit the water at a certain speed,” he explained, doing his sketches and sums on sheets of paper scattered across the dining room table.

Strange things, like wondering if he could sue Nissan because they called one of their models the Bluebird. He dictated a few letters to his secretary … and it was a different, and disturbing Donald Campbell, out for a buck…

He also spent much time with British author John Pearson, whom Campbell had commissioned to write a book about the venture. Pearson was a charming man, with the blackest hair I’ve ever seen on any person, and he arrived with a typical writer’s ailment: deadline trouble.

“I’m a fool to be doing this,” he said, for he was already months behind the due delivery date of a manuscript which his publishers had commissioned. The subject of that book was sex in the south seas.

Poor John had to divide his time between long briefing sessions with Campbell, who would recall the happenings of the past weeks, and long typing sessions in the cellar beneath Elliot Price’s homestead.

lt was a strange refuge for an author: in semi-darkness, amid sacks of flour and sugar, and cartons of canned food and bottled drinks. But there, in the bowels of an outback sheep station, he alternately wrote about the tribulations of the Bluebird at Lake Eyre, and the less inhibited performance of browner birds in Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia.

There was one more attempt, but a fault in the throttle mechanism prevented Campbell getting full power. Again, the track was badly cut.

So we called a halt and all went home, and, for a month, Lake Eyre rested.

A salt lake is a curious thing. lt grows. Like some crystalline creeper, it spreads, seeking objects on its surface that allow it to rise and fan out. A tiny item – a match, or an insect blown from the distant shore – is soon engulfed by the growing crystals, which build upon themselves to form a flat crater-like island of white crust, that looks for all the world like some gigantic pavlova.

Thus, when we returned to Lake Eyre in July much of the surface had changed.

An oil stain had become a wide green elevated platter. Cigarette butts were mounds the size of anthills. Stakes, left to mark the way, were crusted with salt in the shape of upside-down cones.

And the track had hardened, sealing the old ruts beneath transparent fillings that gave the wheeltracks the appearance of blue veins deep-set in trenches of ice.

A smaller team returned to Lake Eyre. One newcomer was Graham Ferrett, who was sales manager of Yorke Motors, the Adelaide company that had supplied the project with Valiants. He had visited the lake a couple of time during the earlier stage, and become a close friend of the Campbells.

Graham, an extremely jovial character, had a number of diverse attributes. He seemed to know everyone in Adelaide – certainly those who counted. And he knew all the landholders around Lake Eyre, for he had served his days as a car salesman selling Land-Rovers.

And he knew how to make the Campbells laugh. He could tackle Tonia at her most serious, and crack the facade with a dozen words. She would call him “fat Ferrett” and hug him, and laugh, and Lake Eyre became a happier place.

Breaking the record was almost an anti- climax.

Campbell flew to Muloorina on July 10. He brought news from England that the Bristol people, makers of the gas turbine, had said it was safe to dial more power into the unit. He could now run to 110 percent of the power used previously. That would get him into the timed zone faster – an important gain on such a short track.

The wind blew for a couple of days, and then it rained. An inspection next morning showed one end of the track was damp, but the central section seemed hard.

The rain had certainly softened the crust, but Lofty Taylor, the Ampol man who had assumed responsibilities for preparing the strip, reckoned it would be firm beneath the thin top layer. It was a guess, of course, but the supremely practical Lofty had been remarkably accurate with previous thoughts about the condition of the salt, and with suggestions about its correct treatment.

“One way to find out,” said Campbell, almost euphoric in his desire to get the record and get out of the place. So he got in the Bluebird and took it for a run.

At 260mph (418km/h), the car seemed steady so he gave the throttle a dab. Within seconds, the car had snarled to 320mph (515km/h). But it was also lugging off course because of a gusty sidewind, so he eased speed and let the car amble back to base.

An inspection of the track was promising. There were Darks on the salt, but they were not more than faint indentations. Lofty Taylor beamed.

Campbell was now keen to go for the record the next day, before more rain came. But the one thing that worried him was that the next day was a Friday.

An intensely superstitious man, he had a dread of doing anything risky on a Friday. Doing anything on the 13th minute of the hour or the 13th hour of the day was also to be avoided.

My name was also a problem. He dreaded having anything around him that was green. He never mentioned my surname. Tonia called me Evan Turquoise.

But the skies were now flecked with cloud and the Muloorina people were sniffing rain in the air. He could not afford to miss a day, to humor a superstitious whim, and so the Bluebird was prepared to run for the record on the morning of Friday, July 17, 1964.

He sought one concession from Villa.

“I want to be able to run sometime after, seven o’clock,” he told his old friend, who was coughing through both corners of his mouth, without dislodging a centrally mounted cigarette, and nodding his head vigorously, as though approving each word. “Whatever you do, don’t start the run at 7.13.”

Leo sent Campbell on his way for the first run at 7.20.

I had Tonia in the car. We parked near the measured mile, on the service strip that ran 500m wide of the main track.

Again, we heard the distant thunder of the engine starting and the eerie, banshee wail of the car approaching at full power. Again, that strange sensation of part excitement, part fear, that knotted the stomach. And the weird mirage effect, of a monster bursting through the horizon, pursued by its vapours. The arch of salt spray, the explosive noise, and then the Bluebird, side-on, beautiful, graceful, incredibly fast and chased by a noise of shattering magnitude. And like some beautiful creature pursued by demons, it vanished in a cloud of gas and spray.

The fastest run yet, 403mph (649km/h). The car was OK. The track marked but not cut. Old wheels off. New wheels on. Fuel in.

Everything checked. Thirty-eight minutes.

The second run began, and we soon knew that something was wrong, for the engine note deepened and the rooster tails of salt spray thickened and clouded the sky. The wheels had broken through the salt crust.

He did not slow. Nine years before, he had begun the Bluebird project to show what Britain could do and what he could do. He had endured one crash, one frustrating year at Lake Eyre, the loss of sponsors, and much public criticism. He could not slow.

He kept his foot down, feeding 110 percent power to all four wheels.

With so much power being unleashed, the track was being destroyed. The front tyres crushed the salt. The rear ones completed the destruction, cutting through the grooved crust and shredding themselves on the razor-sharp crystals.

The back wheels, spinning wildly in deep channels, spat out a lethal mix of white salt peppered with black tread.

The air was filled with tiny slivers of rubber. They fell on the track like black snow.

Campbell could feel the tail of the car sinking, knew he was travelling at a dangerous angle, knew the car was likely to lurch out of control, and kept the power full on. He was still accelerating when he crossed the end of the measured mile.

At the end of the strip, he stopped; certain he had been too slow.

“That wretched track,” he growled.

“The car was so good. It wanted to go so much faster, but we were sinking.”

A man came running from the radio tent. “Four hundred and three,” he shouted.

“Thank you, my friend,” Campbell said icily. He was not in the mood for strangers bearing old information. “I knew the time for the first run.”

“No, no,” said the man, almost too excited to speak. “It’s 403 for both runs. That’s the average. You’ve got the record.”

And in that fashion, Donald Campbell learned of the end of his long quest for the world land speed record.

In fact, the average was 403.1 miles per hour (648.7km/h). A timekeeper later told me the Bluebird passed the end marker at more than 430 mph, still accelerating.

Campbell went back to Muloorina in a daze, like someone who ends his schooldays without having thought about the future. His life had been the quest. And now the quest was over. Successful, but over.

Many telegrams arrived. He read them, and drank too much, and grew merry.

One telegram came from my predecessor, David Wynn Morgan, the Briton who had been project manager in 1963. It read: “You may be a bastard, but at least you’re a quick bastard”.

He read that a few times, drank some more, and went to bed for the afternoon.

There was a party near the army camp site that night. Most of the celebrants were strangers. There was a team of shearers, newly arrived at the station, who got very excited and very drunk, and visitors who had driven up from the south the day before, and were wildly excited that they had cracked the day the record fell. They had been there one day, and we, nine weeks…

Donald Campbell came for an hour or so, but left early. Of all the people at that party, he seemed the least happy.

I thought of something he had told me as we wandered through the sand dunes weeks before.

“I am destined to fail,” he had said, and I wondered if he could understand and accept success…