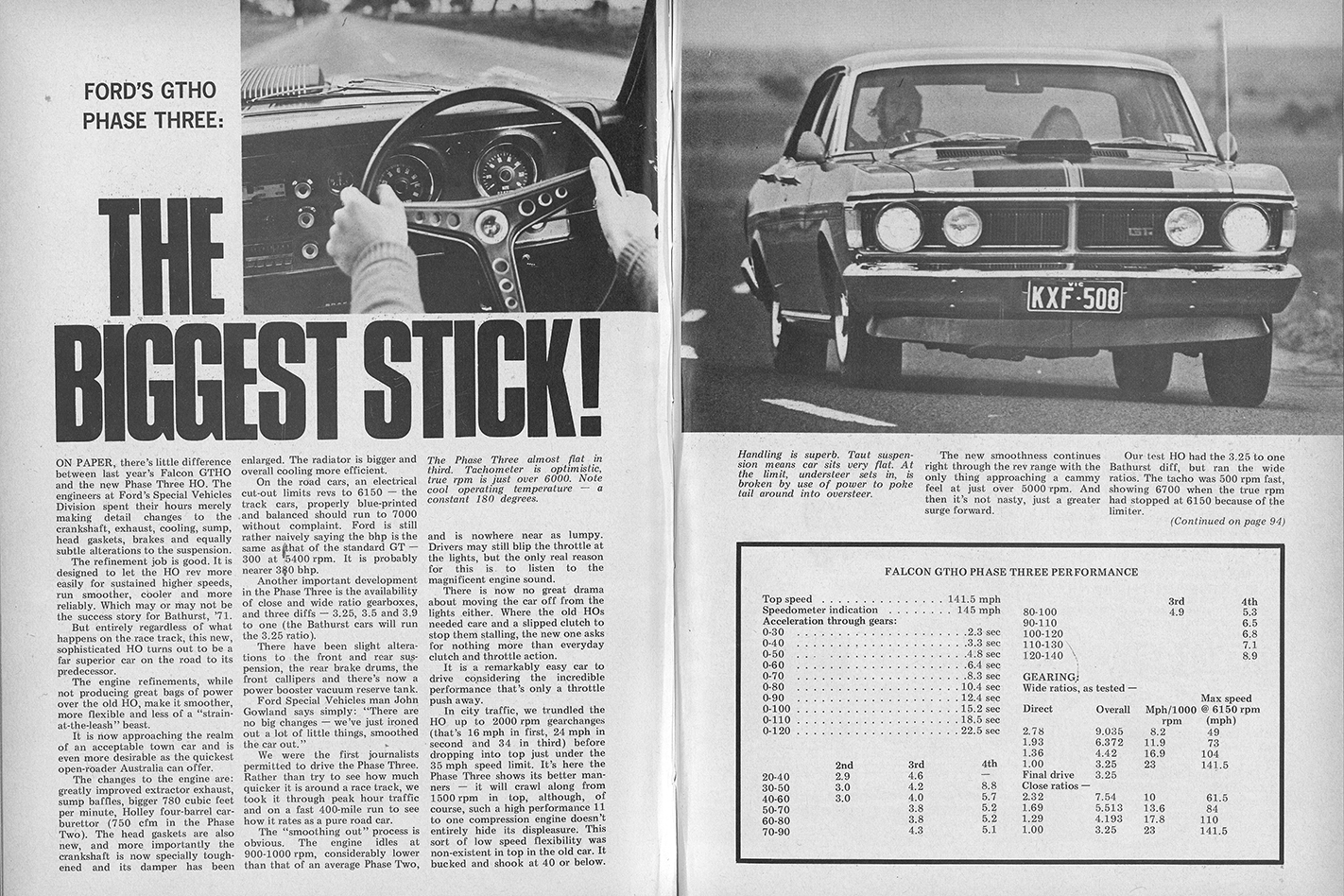

Wheels’ 1971 review of the Ford Falcon GT-HO Phase III was written straight, withholding details of the author’s high-speed research. Here is the story of the Hume Highway drive behind it, originally published in sister magazine Sports Car World four years later.

———-

PAINFULLY, heartbreakingly, as ideals give way to reality, young journalists learn that certain stories are too hot for publication. Some can never be told; others only years after the event took place. This is one of those stories.

It began in the carpark of the Ford Motor Company’s head office at Broadmeadows, near Melbourne, one afternoon in the middle of 1971. A car was waiting there for me in the feeble wintry sun. A mustard Falcon. One of the first GTHO Phase Threes to come off the production lines; so new, its existence was still a secret to all but a handful of people outside Ford. And of those people, here was I about to be handed the keys to the fastest, most awesome supercar Australian had ever produced.

Read former Wheels editor Peter Robinson’s tale about how this story came to be written.

Good organisation or coincidence – I forget which – had it that at precisely the same time as the HO was ready I was in possession of one of the first 5.0-litre V8 Bolwell Nagaris. Indeed, it was the car that had rushed me from Sydney to my assignation with the Falcon, putting the 570km of the NSW section of the Hume Highway behind me in the morning, and accounting for Victoria’s 310km in the afternoon.

Even so, we’d been running late, desperately worried that we wouldn’t make it to Broadmeadows before the Ford people went home, taking the keys of the HO with them. But it was okay because the mechanics were still working on the car even as I telephoned, breathless, from Wangaratta to beg them to wait.

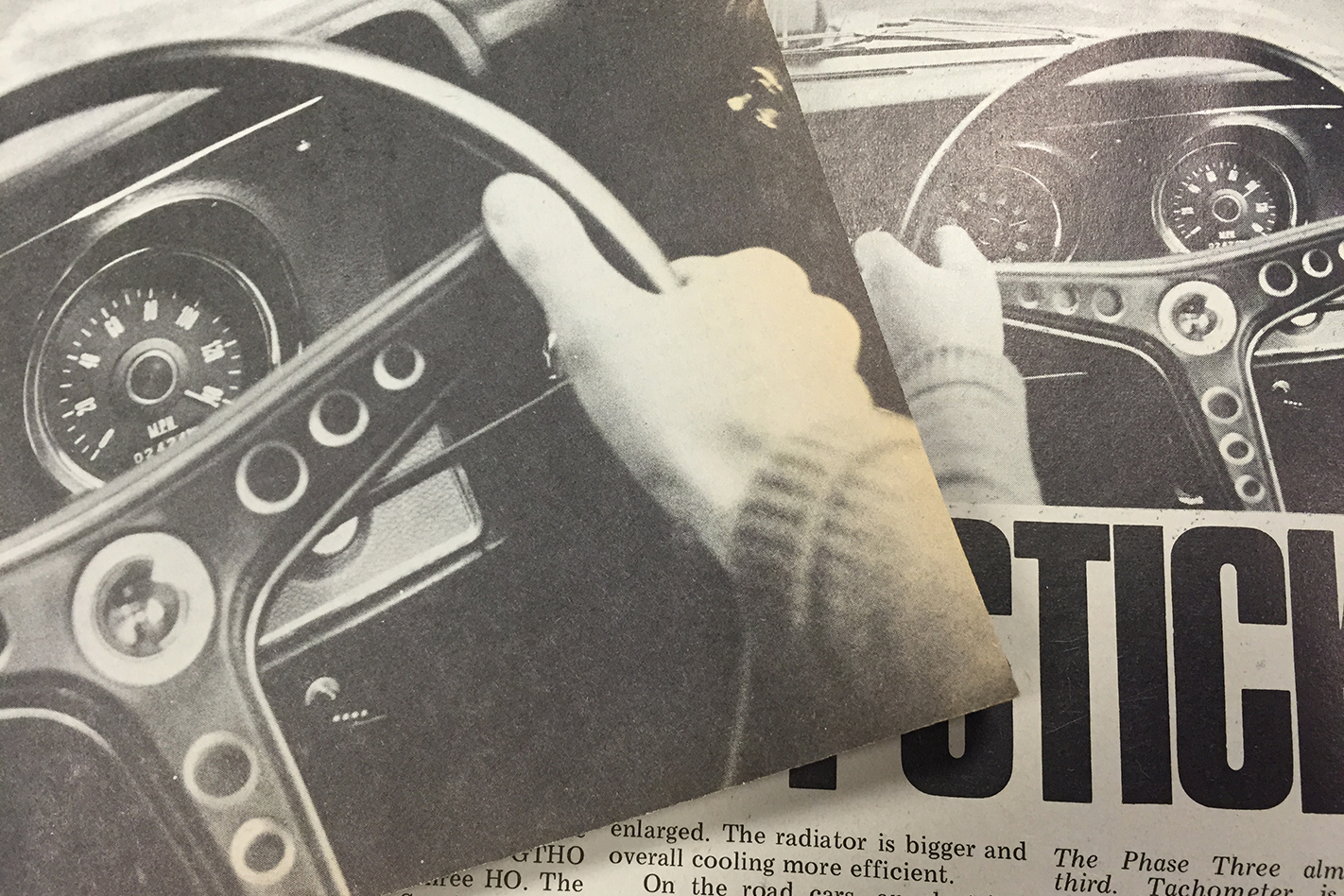

And then I was there, pulling in alongside the thing, unwinding myself from the Bolwell and climbing, gingerly, expectantly, dubiously, half-afraid into the Ford. I can recall not one word the PR man was saying through the open window as the key slid into the ignition. I can remember only the tension, trying to stop my leg shaking and the racing of my brain. And then the trembling of the car and the flick of the shaker air filter in the bonnet as the 5.7-litre V8 churned to the starter and shook in its mounts. It fired, and filled the carpark with a thunderclap of exhaust as intimidating as the snorting of a charging rhinoceros. Then came the popping and sizzling and gulping as the throttle was prodded and the 780cfm bour-barrel Holley dumped too much fuel into the unready cylinders. Give it a little while; I used the time to adjust the mirrors, fine-tune the seating positions, fidgeted in the bucket and tugged the belt a snitch tighter until it nailed me to the squab.

And then I dared to move the car away, feeling a little tremble in the left leg as it fought against that big bastard of a clutch for the first time.

So I, too, trod down hard on the throttle pedal. And braced myself. Without yet completing my arc out through the median strip into the traffic. The car hiccupped … shuddered. Then – bloody hell! – it exploded into action. The front hurled itself forward and upwards like a charging tiger. The back tyres wailed and the tail snapped ‘way out. I speared sideways through the last of the gap in the central reservation. The opposite lock was on, intuitively – no time to think about niceties like steering feel now!

It flicked straight again as it lined up in the outside land of the road towards Melbourne. The engine’s snarling had reached fever pitch. I grabbed second just as the V8 hit its electric rev-cutout. It died momentarily, then picked up again and simply pelted me forward once more. Then senses raced, trying to adjust to the speed. Maximum revs – again. But so soon! Third, and I charged forward once more. And then it was hard on the brakes, getting a slight twitch because I was up to 145km/h in those scant few seconds and about to run right over the top of the Bolwell. We both slowed right down, both aware of just how much performance we had on hand, and how cautious we needed to be. Not because all that go is hard to control. Not at all. But you are so much faster than everyone else you’re out of place in the traffic unless you conform.

So we tip-toed into Melbourne. That early, blood-stirring blast probably did me a great deal of good. It showed me that the Phase Three was an eminently easy car to drive, so much more so than either of its two predecessors, and especially when one considers just how much power lay just a throttle push away. It was so smooth low down, so docile for a thumping great V8 with an 11:1 compression ratio. It was happy enough to trundle down to 1500rpm – 55km/h – in top gear, to idle steadily at 1000rpm compared with something approaching 2000rpm in the Phase Two. I found I was easing up to 2000rpm, changing up into top at around 55km/h. And so I came, very quickly, to feel quite at ease in the HO. Ready to drive it…

Uwe and I picked up two models early the next morning – a Saturday – and headed west to take pictures. I lounged in the warmth of the Falcon while he got on with his work.

And then it was time to start work with the HO. The only open bend we could find was not all that tight. I did one run and found that even 145km/h was too slow to make the car move. It just sat there, hugging the road. Doing nothing. Again: this time flat in third at 170km/h. Again no understeer, no oversteer; just a little bodyroll and the nose lifting jauntily. I went to 180km/h in fourth on the next run and it was still just as uneventful, but I daren’t go faster because I wasn’t yet entirely sure where the limits lay, even though I was getting a pretty good idea.

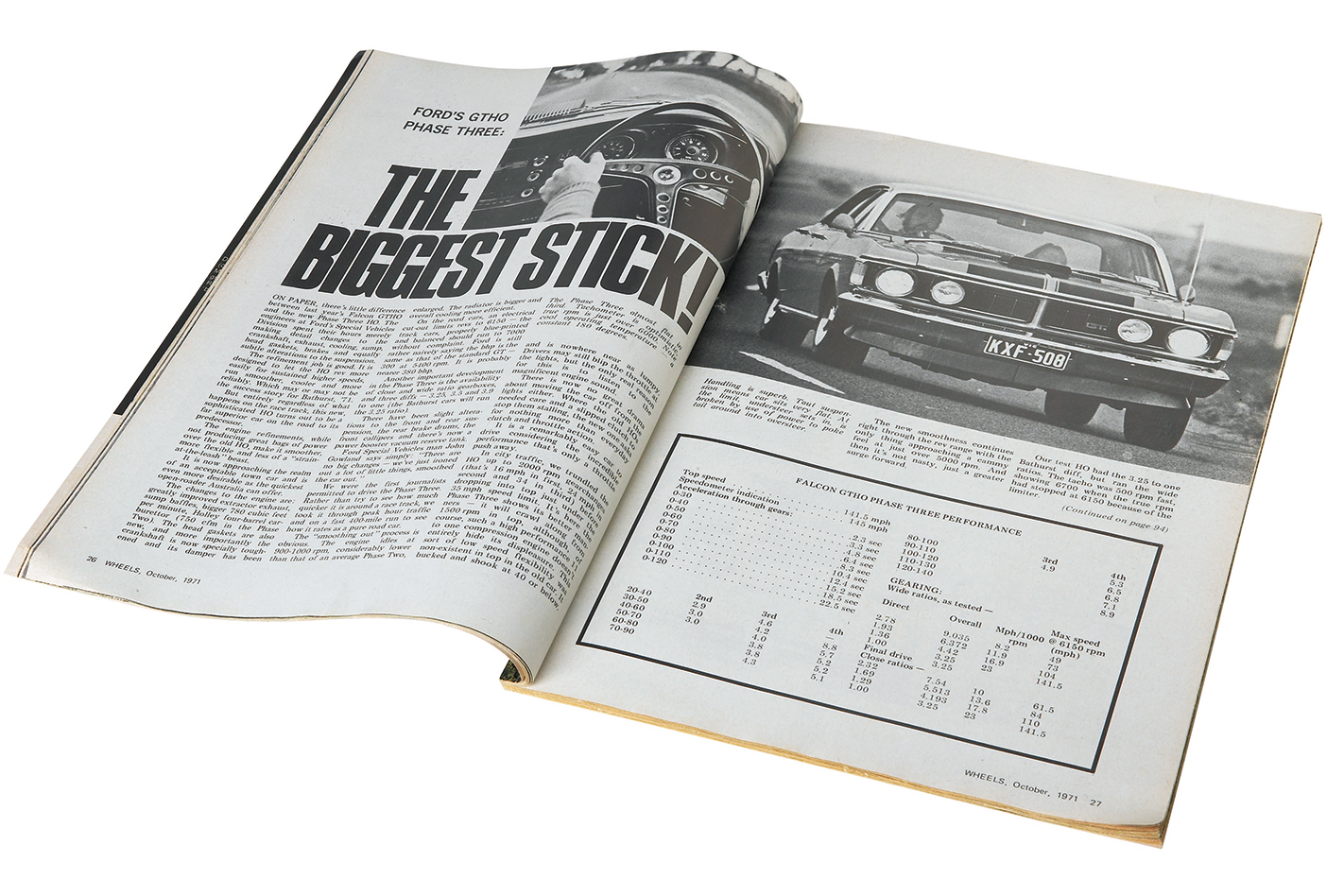

So I ran performance figures instead, ticking off the gear maximums at the 6150rpm redline at 79km/h, 117km/h and 167km/h with top’s maximum unreachable in the space. Then there was the acceleration: experimentation showed that the clutch had to come out at 2700rpm – nothing more and nothing less. If I dropped it at 2500rpm the engine died a little against the grip of the wheels. If I popped it at 3000rpm there was wheelspin for around 200 metres, again wasting time. So 2700rpm it was. And 0-160km/h in 15.2 seconds came up on the watches. But so effortlessly…

But what the hell, we still had the HO, didn’t we?

Indeed yes, and unbeknown to us at that moment, we were soon to subject it to one of the most exhilarating tests it would ever undergo on the road; to use it for what I suspect is one of the most remarkable journeys ever run in Australia. To thunder it flat in a drive etched for ever on the memories of the two of us who did it.

But for the moment we found ourselves tooling quietly through the cold Melbourne drizzle. Saturday night. No plans. No enthusiasm. Then something – I don’t know what – made one of us suggest going to Albury, 320km away on the Victoria-NSW border.

So we gunned the HO around, hit Elizabeth Street and headed north into the night. It was 7.30pm.

The rain grew heavier and the night nastier. There wasn’t much traffic, and what there was was going the other way. I don’t recall much until we were past the little Hume Highway town of Seymour, but I expect we’d been alone with our thoughts and the murmur of the radio, soloist to the steady background swish of the wipers, the hissing of the tyres and the downbeat throb of the V8. I only remember the ease of driving the car; how much at home I now felt in it, with a real idea of its capabilities now forming clearly in my mind. How comfortably it carried us, its lights hacking through the night. And then came the long, fast bends you strike after Seymour. Open bends. And I can remember the way the car just seemed to think itself through them, undeterred by the rain and travelling at ever-increasing speeds and showing me how strongly it could grip and how finely it was balanced.

I flicked a glance at the speedo as we came into it now in the HO. I barely believed it – 200km/h. But there we were, rock-steady, the car just slicing on through, set up by the merest throttle lift then kept on line with gentle pressure on the pedal once more, and the tiniest smidgin of steerage on the big wheel. Everything about it was so clean, so beautifully and clinically balanced, like walking on a razor’s edge and feeling the elation of not slipping off. And that moment remains as one of my high points in years of road-testing. It was perfect – so perfect it was almost nothing.

We continued on holding 200km/h for what seemed like dozens of kilometres, and the only reason we didn’t go faster was that at precisely 202km/h the windscreen wipers began to lift off.

Then we were in Albury, purring gently through the glistening streets after a run that contained nary a sideways twitch, never a sliver of understeer, not one zizz of wheelspin. It was exactly 10pm. We had covered the distance faster than either of us would have imagined possible even in ideal conditions, let alone amid the elements’ atrocities of that night. Yet it was also the tamest, most uneventful trip either of us had had from Melbourne to the border. We were into the inner sanctum of the GTHO’s world.

And there was even more to come the next day.

Our arrangement with Ford was to hand the Phase Three back at nine o’clock on the Sunday morning and then get a lift back to Sydney with a Ford employee who happened to be driving from city to city that day.

We checked the tyre pressures, polished the windows clean, and at 7.02am we left for Melbourne.

The morning was as perfect as the night before it had been foul. We went full out through the gears as we cleared the last speed limit of the border town complex with the HO now warm and ready, thundering past a couple of cars and a semi. The car’s nose was thrusting forward and upwards with the power once more, we were again enjoying the feeling of being pressed back into our seats as the thing was given its head. At last it was free of any and all restrictions. There was only the open road ahead.

Again we chewed up the kilometres and spat them out. In remarkably short time we were striking the long straights of the Hume about 225km north of Melbourne, and with the speedo steady at 200km/h I squeezed down still farther on the accelerator as the ribbon of road speared straight ahead.

The shaker heaved in the bonnet, the car sort of shrugged and the nose rose up even further from the road. It might have been a tiger kicked awake; the noise alone said that. The speedo needle went determinedly around the dial, and soon it was showing 233km/h. A true 227km/h.

But whoa! The engine started missing; fluffing and farting. For God’s sake – the rev-limiter! We’d run right up to it. In top gear. A full 6150rpm (the tachometer actually said 6700rpm; it was optimistic).

For minutes, for kilometre after kilometre, we stayed like that. The car was like a locomotive on rails, never deviating an inch from its path. The messages from its rock-steadiness came back through the wheel and the seats as unmistakably as pinpricks.

I remember how I felt. Relaxed, but razor-sharp, peering ahead a kilometre or more; my eyes, my brain, my nervous system forcibly lifted to a new height to deal with the speed. You feel so competent … so potent. Your mind seems to magnify everything, to pick up an extraordinary amount of information and to digest it amazingly quickly. It’s called concentration, and it’s delicious.

Road conditions and traffic allowed us to keep the HO close to its maximum speed for many more kilometres. But nearing Melbourne we came back closer to 160km/h most of the time, using the tremendous top-end acceleration to maintain a fantastically high average and to overtake in a quick rush of power and safety, since our exposure time was so brief and our controllability so vast. We toyed briefly with the stopwatches again, finding out to our amazement that 160-193km/h took a paltry 6.8sec and 193-225km/h just 8.9sec. And that is top-end performance, with all the excitement and advantages it entails, and simply unavailable in anything else this side of a Miura or Daytona or Berlinetta Boxer or Countach.

Stunned by the car, amazed yet again at such an extraordinarily rapid but effortless trip, we pulled at last into Ford’s offices at Broadmeadows. It was one minute to nine.

Neither of us spoke. We just shared the silence of the moment, feeling a special sort of elation. Then we lifted our gear from the HO and locked it up and left.

Neither of us spoke. We just shared the silence of the moment, feeling a special sort of elation. Then we lifted our gear from the HO and locked it up and left.

I later thought of how I’d write the story, not yet realising that there was no way I could tell it all. I began to dream of another story. A race, full-out, no holds barred across the Hay Plain in NSW. Between Australia’s finest GT and the Lamborghini Espada, Italy’s finest four-seater. It almost happened, too, but with the Phase Four HO and not the Phase Three. We had it all planned, but then the politicians, remembering the hysterics of the Sunday newspapers when they had finally gotten wind of the Phase Three HO’s pace through the figures listed with my abridged story in Wheels, killed off the Phase Four before we could stage it. I only wonder now if those same politicians and newspaper beat-up merchants ever really know what the old Phase Three HO’s capabilities really were.