Most of the cars we cover in Wheels’ Modern Classic section reach that status through sheer durability. Years of continuous improvement hone something that was rough and ready into a polished gem. Of course, the opposite can happen too.

Cars that burst onto the scene in a blaze of youthful verve often mellow into comfortable middle-aged spread. Once in a while, we get that rarest of things: a hero car that appears and then vanishes almost as quickly as it arrived. For a magnificent case in point, look no further than the Lotus Exige S1.

Its production run lasted but a year. From its introduction at the Brands Hatch round of the Lotus Motorsport Elise race series in April 2000 to the last car coming out of the Hethel plant in mid-2001, 604 cars were assembled, 177 in left-hand drive.

They’re a good deal rarer today. The car you see here is one of only eight that were officially sold to Australian customers from new, of which this is the only matching numbers original left on these shores, so it’s a bit of a unicorn.

To the uninitiated, the Lotus Exige S1 looks like an early Elise with a hardtop and a set of spoilers, and some Elise owners have converted their cars to look like an Exige with replacement glass-fibre body parts. The real thing was a far harder and angrier thing than any Elise extant in 2000.

While the Elise launched with a modest 88kW Rover K-Series lump behind the driver’s head, power crept up amongst the roadgoing cars almost annually. The 108kW Sport 135 special edition came in November 1998, with the series production 107kW variable-valve 111S not long later, in January 1999. The 112kW Sport 160 special debuted just ahead of the Exige, in February 2000.

The madcap Elise Sport 190 foreshadowed what we were to see from the Exige. Launched in February 1998 and on sale through to early 2000, this was a factory conversion aimed at hardcore track fiends and delivered 143kW in a package that also featured uprated suspension, brakes, safety equipment, gearbox parts, and more focused wheels and tyres.

It was also eye-wateringly expensive, which goes some way to justifying why only seven were ever sold, but as a proof-of-concept, it was something very special.

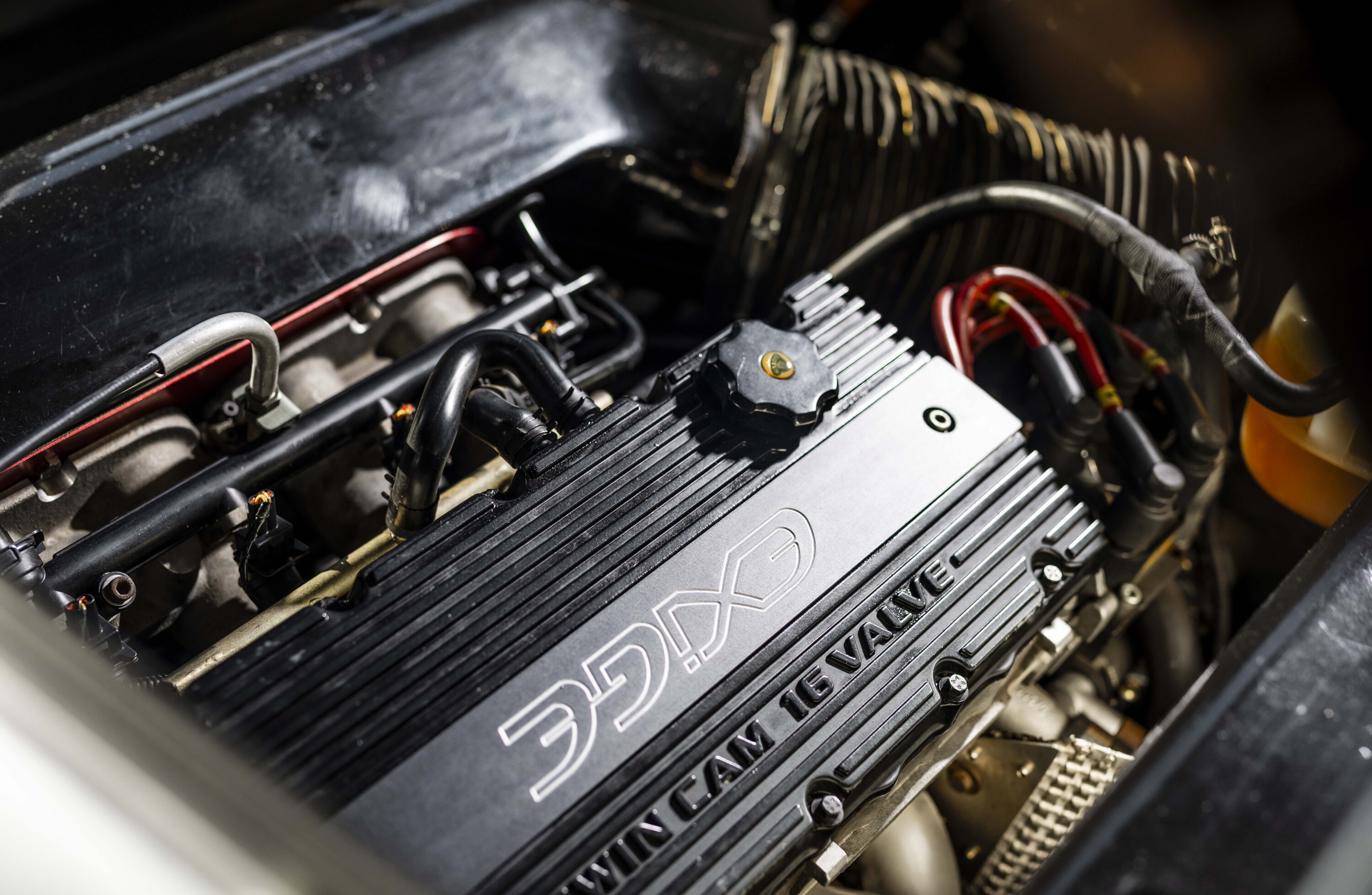

At the heart of the Sport 190 was the Very High Performance Derivative (VHPD) of the venerable K-Series 1.8-litre lump. Rattly and truculent at idle, with that great sound of piston slap, it was far from the most melodic powerplant, but it thrived on revs and sounded as if it was trying to tear a hole in spacetime as it approached its redline.

In the Exige, peak power arrived at 7800rpm, and you needed to be quick with the pedals and stick, because it would run into its 8000rpm rev limiter almost immediately thereafter.

As standard, the Exige made 133kW, or 143kW if you opted for the $1800 Track Pack (decat) version. The peak torque is a modest 171Nm at 5000rpm, but that hardly matters when you’re trying to haul a mere 724kg up the road. Of course, some wanted more.

More pace, more refinement, more tuneability and so on, and a surprising proportion of Exiges have been converted to run the Honda K20 engine with some also using Ford or Audi units. Of course, there’s the fact that those early VHPD engines weren’t the very last word in durability.

It seems almost a cliché to start talking about head gasket failures in relation to the K Series engine, but, yes, the Exige S1 was occasionally prone to a bit of mayonnaise under the oil filler cap.

The engines for the Exige S1 were assembled by PTP. For the S2 Sport 190, work was brought in-house to Lotus, with better results. Nevertheless, it was an involved job to get that sort of power from the decade-old atmo K-Series, with the VHPD engine featuring a revised head design, a nirtrided crank, a lighter flywheel, modified throttle bodies, forged pistons and a lot of other detail changes. Many Exige S1 owners will recommend vernier timing pulleys and an Emerald ECU with a decent map for a torque curve with fewer holes.

Levering yourself into an Exige S1 to take advantage of the VHPD’s charms isn’t the easiest process. With wide sills and a low roofline, it’s more of an undignified slump into the driver’s seat, especially if you’re fairly tall.

Once you’ve manoeuvred your legs in, accustomed yourself to the faintly acrid smell of GRP and realised that the rear-view mirror is purely ornamental, the baby Lotus is surprisingly comfortable.

Key the car on, watch the period Stack digital displays flicker into life and select first from the long wand and it all feels a bit underwhelming. The unassisted steering is heavy, the brake pedal feels wooden and the throw of the gear lever ends with a crunchy slot into gear. Then it all begins to make sense.

As the gearbox oil warms, the shift effort reduces. The steering that seemed so obstreperous mere moments ago comes to life, sniffing out cambers and tipping its own way into corners. It’s magical. The brakes – cross-drilled and vented 282mm discs with AP Racing opposed-piston front calipers and floating Brembo single-pot rear calipers aft – deliver more than enough feel and response.

Really punish them and the front pads can warp, which you’ll feel as an indistinct brake pedal that makes heel-and-toeing vague, but there are fixes available for this.

Drive an Exige on a challenging road or circuit and it’s a genuinely thought-provoking experience. Yes, it’s hot and cramped and noisy, but the payoff is massive. The question that coalesces over and over is ‘have we got the whole progress thing wrong?’

Bigger, heavier, more complex and more expensive cars might well be safer and more efficient but, for some of us at least, driving doesn’t get a lot better than the recipe delivered by an Exige S1. It’s mesmerising.

Maybe there’s something to be said for focusing on one thing and doing it really well.

The Exige certainly did that. I learned the Spa race circuit in Belgium by following Lotus chassis engineer Matt Becker for lap after lap as he pedalled the Exige around and I swapped into ostensibly faster vehicles that, one by one, wilted as the little Lotus kept on clipping apexes. It was an object lesson in working smarter rather than harder.

At its core, the bones of the Exige were good. Becker would occasionally chunter about the shift quality or the Koni dampers, but there was a fundamental rightness to the Exige from day one. For its era, the aluminium chassis was incredibly stiff, and the double A-arm suspension had little to go wrong unless, that is, you tinkered unsuccessfully with the spring preload and front anti-roll bar. The advice in that case was always the same. “Put it back to factory setting.”

As was so often the case at Lotus, developing the Exige was an exercise in minutely finessing a bunch of bought-in and often fairly prosaic parts to work in harmony with one another.

Both Becker and his colleague Gavan Kershaw, would spend hours beating round the lumpy old track at Hethel in order to develop that cohesion. You’d hear them muttering about tyre sidewall hysteresis, moments of yaw gain or front to rear phasing response and realise why these guys were held in such esteem by every other chassis engineer in the car industry.

Wheels’ first experience with the Exige came in October 2001 when Nathan Ponchard grabbed the keys to a Chrome Orange 133kW car and strapped on the timing gear. It’s fair to say he was impressed.

“Despite boasting top-notch power-to-weight potential (183kW per tonne), the Exige feels like it could easily handle another 30kW,” he claimed. “Purely because it’s blessed with exceptional poise and astonishing grip – the Yokohama A039s, specially developed for lightweights like the Exige and mounted on glossy black Rimstock alloys, play a big part here.

The rear end is amazingly secure and full-throttle, first-gear exits from 15km/h hairpins betray little more than a mild scamper for traction. No smoking wheelspin, show-pony powerslides or scaredy-cat skid control interference. The Exige doesn’t have it, doesn’t want it and doesn’t need it.”

That example lived up to a Lotus stereotype by developing a slight miss at about 5800rpm, which meant that the Correvit data logger wasn’t showing figures that got particularly close to Hethel’s 4.9 second 0-100km/h claim, the tape churning out a 6.8 second showing.

No wonder Ponch felt it could handle another 30kW. Exiges can be tricky to get off the line and the 0-400m time of 14.8 seconds that the crew achieved at Sydney Motorsport Park is about what you might expect from a modern MX-5. In optimum conditions, shave a couple of seconds off that before the Exige’s aerodynamics start conspiring against it.

The asking price back in 2001 certainly wasn’t lightweight, with Lotus wanting $130,171 for Aussie cars. Predictably, these were about as stuffed with extras as an Exige could get, with air conditioning, an alarm, Alcantara trim, leather seats and a radio installation kit. On the options list were an Alpine stereo that fought a losing battle against the sound of the K-Series and metallic paint at a hefty $2450.

Now? That’s a tough question because they’re so rare in Australia that they almost fall into the realm of being worth whatever someone’s willing to pay.

The later Toyota-engined Exige variants are more comfortable and more reliable than the S1, and represent a viable alternative as a trackday special to something like a Porsche 911 GT3. They don’t possess the rawness nor that 5/8ths scale Group C emigré look of the original. That’s part of the appeal that keeps fans of the Exige coming back.

You need to be committed in order to run one in its UK home market where there’s a grassroots network of engineering backup when things inevitably go wrong.

Over here it’s another level of complexity again. The Exige suffers from many of the tedious, snagging issues that the Elise was known for such as failing clam release cables, misting headlights, broken alternators, crazing and cracking glass-fibre, radiator leaks, various clips failing, worn suspension parts, glued trims falling off and such like.

These things tend to define your Lotus ownership experience. Some will dabble, get frustrated by the constant demands of the cars and then return to something like a Porsche, whereas others will actively enjoy overcoming this series of challenges and find a certain camaraderie among those that do likewise.

The parts that were prone to fail, such as the cheap plastic radiator end caps, will have long since been replaced with superior items.

What’s more, even if the worst comes to the worst and a head gasket fails or the cylinder liners wear, the fix is relatively cheap in relation to the total cost of the car. That’s because rarity has made these cars ever more desirable. Couple that with the fact that the Exige S1 is just about to cross the 25-year threshold making it eligible for personal import to the US and you can see why most owners are wearing that “No lowballs, I know what I’ve got” face.

When buying the big things to check for are accident damage and corrosion, the two issues often linked. Punt an Exige into a tyre wall on a track day and it can be very hard indeed to get the tub straight, as the front wheel tends to push the wishbones into the suspension pickups on the chassis, bending or breaking them.

Where the tub is bonded aluminium, the rear subframe and the rear suspension uprights were steel and, as anyone with a passing knowledge of chemistry knows, these two metals don’t really rub along that well, setting up an galvanic reaction which leads to corrosion of the anode, which in this case is the aluminium part. The electrolyte to help the process along is water from the road surface.

Inspecting the tub for accident damage and the suspension pickups for corrosion is absolutely key because, unlike most other cars, you can’t just break out the welder and fix any problems, because aluminium and glue.

Again the prices of Exiges comes into play. A few years ago, this would have represented a vehicle write-off, whereas now, it’s financially viable to procure a $25k replacement chassis and have the rest of the car bolted to it.

The Exige’s payoff always justifies any expense outlaid in maintenance. Cars just aren’t built to feel like this any longer. Even the last of the Series 3 Exiges that ran out in 2021 don’t have the immediacy and the sheer lightweight authenticity of the S1.

Julian Thompson’s original Elise design may have lost a degree of its aesthetic delicacy in this guise, but gained a curious melange of prettiness and menace that really shouldn’t work but somehow does. It’s a stunning looking car and one that looks ever more alien in a carscape of huge and overweight bloaters.

How can a car this brilliant ever have been so rare? Original cars like the one you see here are rarer again. It’ll be remembered as one of the greatest cars Lotus ever built, and that’s a high bar in and of itself. It may have enjoyed a mayfly-like production run but its legacy endures.

We recommend

-

Reviews

ReviewsLotus Exige S Roadster review

A Lotus Exige with luxury bits? What’s going on?

-

Reviews

Reviews2013 Lotus Exige S Review

If you like it hardcore, you’ll see the light

-

News

NewsThis is the fastest manual we’ve ever tested

Our independent testing reveals real-world 0-100km/h, quarter mile and 0-200km/h time of the 2019 Lotus Exige 410