Only engineers Jörg Bensinger and Roland Gumbert, who sold the idea of a four-wheel-drive high-performance car to Piëch, ex-Mercedes racing car engineer Hans Nedvidek, and project leader Walter Treser, plus a few mechanics in the experimental department, were aware of Piëch’s ambitious plan. They had to be, since they were responsible for building the car.

Thinking long-term, Piëch (the grandson of VW Beetle engineer Ferdinand Porsche), knew what he had to do and saw the potential for a technology-led assault on its German rivals. This car would be the first … if Audi could convince the VW establishment of its potential as both a road car and, for added credibility, as a possible World Rally Championship contender.

Piëch’s improbable aspiration for Audi, then the maker of, “ordinary cars liked by butchers and farmers”, was to use the new model as the first step in a 25-year effort to challenge – and eventually match – Mercedes-Benz and then fast-rising BMW as the global automotive prestige powerhouse.

The autocratic, visionary Piëch, who took over Audi’s R&D in 1975, told designer Martin Smith in his job interview that he wanted, “Audi to become more than a small Bavarian car maker.”

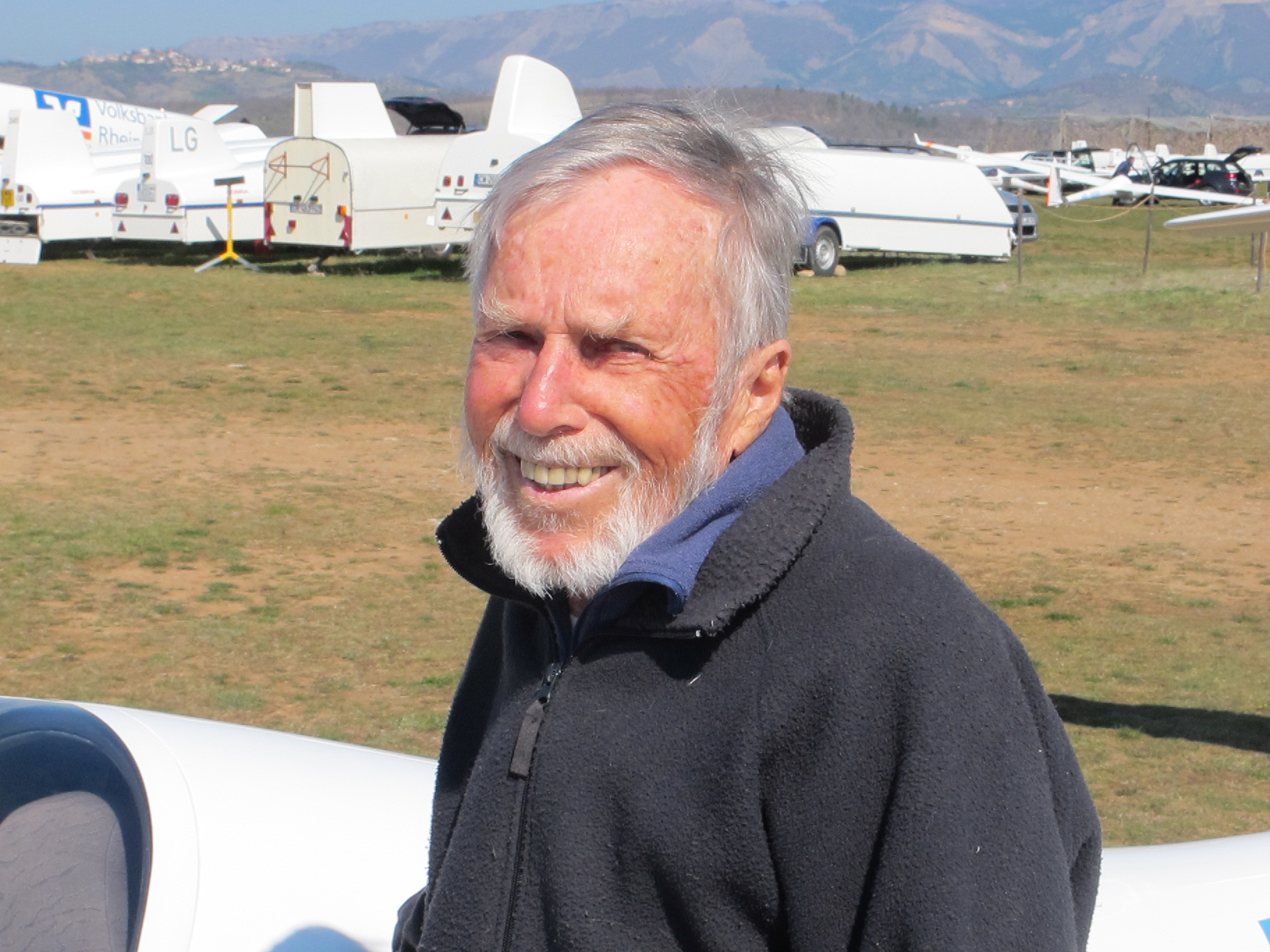

Eyes sparkling, a friendly smile partly hidden behind his white beard, and knowing we are delving into his remembered past, Bensinger wants the Quattro story to start at the beginning: in 1962 at Porsche, when he worked on the “very interesting” mid-engine, rear-drive, double wishbone-suspended 904. It was, he says, more interesting than the new 911 or the 356 handling “disaster”.

For the chassis engineer, the Porsche experience was the beginning of a fascination with disparate driving layouts. Head-hunted to BMW, he later joined Mercedes, which meant Jörg spent the next decade working on front-engine, rear-drive cars. But opportunities at Mercedes were rare, and the age-based hierarchy meant his career stalled. In 1971, Bensinger moved to Audi to join former Mercedes engineer Ludwig Kraus who had also moved to Audi. At Audi it was all front engine and front-wheel drive.

Bensinger quickly discovered that in Finland’s icy winter conditions the high-riding 56kW Iltis easily ran away from the more powerful 127kW two-wheel-drive Audi 80. What was the use of all that power if it couldn’t be applied? Surely, he thought, a sporty all-wheel-drive sedan with superior traction and cornering behaviour would be the perfect solution for a high-performance Audi. That was in 1976. Four years later, the Quattro was launched to acclaim at the Geneva show, and Audi was on its way.

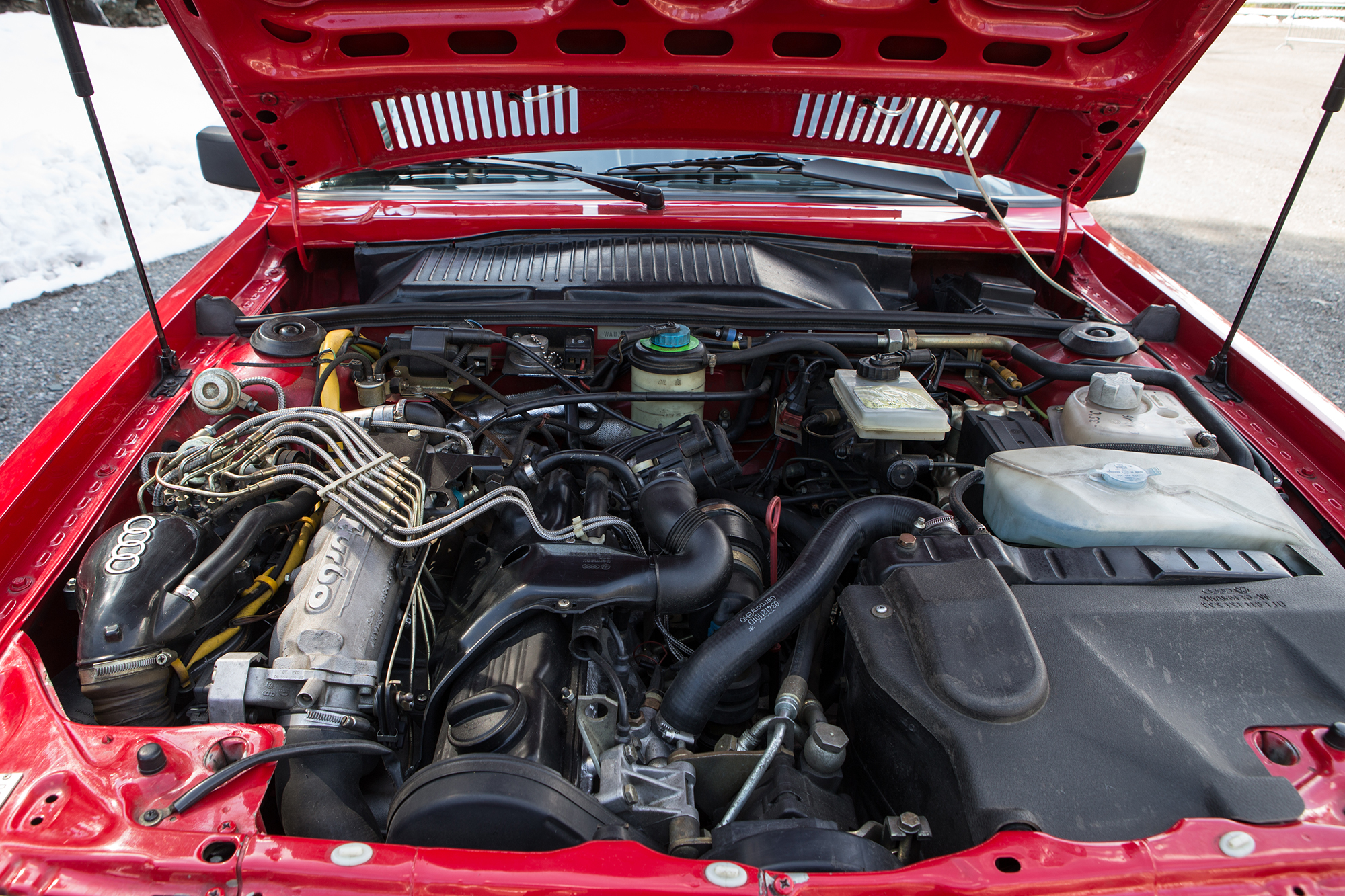

In March 1977, Audi’s tiny team took a front-drive 80 and, raiding the VW and Audi parts bins, fitted the permanent four-wheel drive system from the military VW Iltis (a purely Audi development), the five-cylinder 118kW turbo engine from the 200 Turbo, and MacPherson struts front and rear (the rear being the 80’s front set-up rotated through 180-degrees). A new gearbox replaced the Iltis transfer cases with an ingenious hollow shaft through which power flowed in two directions to the front and rear wheels.

Now it was time to expose the prototype to the top people from Wolfsburg, the crucial step in obtaining formal production approval from VW management for a car unlike any other.

In January 1978, Bensinger took the A1 deep into the Austrian Alps. Driving the 1795-metre Turracher Höhe pass involved negotiating Europe’s steepest road; a gradient of a staggering 34 percent, too steep to walk. On hand to witness the test were VW’s senior sales and marketing people, including sales director Dr Werner Schmidt.

He tried a Mercedes 280E, a BMW 528i and an Audi 100, all on winter tyres, on the steep, snow-covered forest road. The rear-drive models stopped after about 100 metres, the Audi after another 30 metres. Ignoring winter tyres – forget chains – the ‘Quattro’ romped up the daunting, icy slope that had so easily defeated the conventional front- and rear-drive cars.

Even then, Schmidt wasn’t totally convinced. He wondered who would buy the 400 examples needed to homologate the car for rallying. Further testing showed it was almost as quick as a Porsche 928 on a dry Hockenheim race track. Finally, at Piëch’s direction, Volkswagen chairman Toni Schmücker drove across a saturated, sloping field outside Ingolstadt to discover how effortlessly the car delivered grip in conditions that overwhelmed front-drive models.

Schmücker, wildly impressed, gave the green light.

Smith, who has a house in the Luberon area of southern France (luckily for me, just 100km from Bensinger), joined Audi from Porsche and Ogle Design in 1977. Interviewed by Piëch, “very much a man in charge”, Smith was told Audi was on the move. His first task, as head of advanced design and special projects, was the creation of the Quattro.

“The 80 coupe was almost finished and it was my job to convert it into the Quattro,” Smith says. “My brief was to do something that visually transmitted the idea of the world’s first four-wheel-drive sports car.

“Piëch wanted the car to look sporty, technical and aggressive while, for budget reasons, to retain the steel body of the 80 Coupe. I worked with a clay design model and changed the fenders, the front end, rear bumper, and added the rear spoiler, after hours in the Wolfsburg wind tunnel working on the best shape. I also came up with the blister flared arches. They’d been seen on racing cars, but never on road cars. We tacked them on to the fenders by cutting and welding the bits. I wanted the tops to be a bit softer but that arched top gave the Quattro its character. You can still see the blister line has returned on the new A6.”

“You had to be very sure of yourself when talking to Piëch. He was very direct, but positive rather than intimidating. Until I moved to Opel, I’d never heard the term ‘business case’. It was Piëch’s genius that came up with and forced through four-wheel drive, turbocharging, direct-injection turbo-diesels, alloy construction and low aerodynamics.

“Whatever he dreamed up at the weekend, Audi would be doing on Monday. There was no marketing involvement, no business case, we didn’t have any of that. What he wanted he got.”

In May 1978, VW approved the plan to go into production with a model called Quattro, the name coming from Walter Treser. Revealed at the 1980 Geneva show, the Quattro seduced an enthusiastic press and instantly became the supercar of the 1980s.

“It was always in my mind that it would just be a road car,” says Bensinger. “But, at that point, Audi was not in the position – like BMW and Mercedes were – to introduce something like this without promotion and publicity behind it. It was a very, very important car for the company. Piëch and I both wanted to be better than the others; the four-wheel-drive car would make it possible.”

That meant using rallying to prove that the concept was not just quick in slippery conditions, but also in the dry. Drivers Walter Röhrl, Michèle Mouton, Stig Blomqvist and Hannu Mikkola were the marketing campaign. Audi won the WRC manufacturers’ title in 1982 and 1984 and the drivers’ title in 1983, and across an 11-year production run sold 11,452 Quattros.

The numbers prove the Quattro’s seismic impact: In 1975 Audi sold 205,218 cars globally, rising to 1,871,386 in 2018. Last year, all-wheel-drive Quattro versions of Audi’s range took 45 percent of production … and all its German rivals featured four-wheel-drive cars.

In 1988 Bensinger was headhunted by tier one supplier GKN to become product development director.

“Audi was my home, it was a hard decision,” says Bensinger. “Piëch asked me why I was leaving. I told him, ‘We have lost confidence in each other’.”

Still, he admits, “Without Piëch we could not do it. Nearly nobody at Audi was for the Quattro. He was strong, but the relationship was always difficult.”

Was the Quattro the highlight of his career? “For sure,” Jörg says, smiling.

Unloaded from the truck, they sit together, two proud warriors. The setting is perfect: a quarry, the quintessential late 1970-early ‘80s automotive photographic location.

We all know the Quattro was designed before Audi discovered the wind tunnel with the 1982 100 and its 0.29cd. There is no denying the purposefulness of the design with its blatant, flared wheel arches and deep glass areas, but from every angle this is an old design, all vertical and upright, squared-off corners and boxy angular, with long overhangs and a 0.42 drag co-efficient that belongs in the ‘70s. Yet the styling remains determined, resolute and instantly recognisable: this is a much respected classic.

We’re in for one disappointment: research reveals that the old road, with its 34 percent gradient, is now closed to the public, replaced by a far safer two-lane route with a mere 23 percent slope. Still, this lone access road on either side of the pass provides plenty of driving thrills, climbing over 1200 metres across 51 km from one valley floor to the next, undulating one moment, meandering the next, flinging in a few hairpins and always flowing. It’s close to driving perfection. Turracher Höhe is now a popular snow resort but today, between the skiing and trekking seasons, traffic is minimal and the road surface dry.

Even if it doesn’t feel all that fast, the basic quality of Bensinger’s concept means that the Quattro is easy to drive quickly. Once on boast, beyond 3000rpm, the thrumming turbo-five comes alive and delivers a sustained shove. The secret to its speed across the ground is the ability to maintain momentum. Even on the modest 205/55 R15 Toyo winter rubber – were tyres on performance cars really so small? – the Quattro is supremely composed, pushing gently into understeer on fast corners at the limit. There’s an immediate perception of immense stability and handling that remains fuss-free and secure, especially on wet roads. This car flatters the driver.

The Quattro’s age is also revealed by the slower-than-expected steering, especially around the straight ahead, and a thin steering wheel rim, the leather uncomfortably slippery from decades of use. The Quattro is easy enough to place on the road, but this is not modern-precise steering and it does dart and weave under heavy braking.

Our ‘second-generation’ Quattro eliminated the early car’s flawed gear ratios, closing the gap between second and third and permitting taller overall gearing. It remains low geared, to the benefit of flexibility, and the long-throw gear change, too, is faster and smoother than I remember. The car is also much noisier. What can’t be denied is the Audi’s traction. Point the Quattro at a ski-slope as we did and there is no wheelspin, no hesitation, just instant forward movement. It’s impossible not to be impressed.

Early cars lacked anti-lock brakes, and more than a few drivers discovered that four-wheel drive might solve adhesion issues, but can’t defeat physics when braking on slippery surfaces. Apparently, front-end accidents were plentiful.

The cabin is airy, if black, the early, very 1980s tech attempt at digital instruments difficult to read. What works is the Audi’s excellent driving position, despite the fixed steering wheel, and the comfortable bucket seats. The rear chairs offer generous space for two adults, so this is a true four-seater.

From launch until 1982, the car was available only in left-hand drive, but a few came to Australia, though it was never officially imported. Kerry Packer, once the owner of Wheels, bought three. The first was converted to right-hand drive by Kevin Bartlett, the second was a later right-hand-drive car, and he kept a third in London, until all were replaced by Nissan Skyline GTRs in the early 1990s.

To get to Turracher Höhe, I’ve driven Audi’s new e-tron, the German manufacturer’s first fully electric production vehicle. Before we set out, I hoped to find a link between the Quattro and the e-tron. Beyond the fact that both are badged Audi and are four-wheel drive, there is none. The Quattro is the inspired result of an engineering genius intent on upsetting the status quo. Audi’s ‘Vorsprung durch Technik’ – ‘Progress through Technology’ – advertising campaign might have been written by Piëch specifically for the Quattro.

The e-tron belongs to a different world. Ingolstadt is now driven not by individual engineering brilliance but by the same marketing genius that created, among others, the hugely successful A5 range. The e-tron looks like any other Audi SUV. It ignores the potential packaging benefits of electric cars. I can’t imagine Ferdinand Piëch allowing such conservatism.

Audi design boss Marc Lichte admits Audi looked at more radical designs, but says marketing favoured a more familiar look. The thinking, apparently, was to ease the transition to electric cars. So no bat-wing doors, no glass dome roof, nothing weird, resulting in something that’s positioned close to the Q7 in size, but with better proportions and evolutionary styling. Still, we have to ask, does an electric car need a traditional radiator grille?

Audi’s familiar design language carries over to the interior that borrows most of its technology from the new A5/A6/A8. The only major exception is the new lovely-to-use new forward/reverse gear selector. The cabin is also a modern, high-tech wonder. With the same MMI Touch Response system now common to Audi’s bigger cars, a pair of pressure-sensitive haptic-feedback touchscreens control almost everything outside the steering, braking, and acceleration, which is effortless and swift without touching on ludicrous. The digital instrument cluster can even display Google Earth navigation. It’s now a cliché, but still the truth: nobody does interiors better than Audi.

Range? The best we saw was a predicted 327 km, a long way shy of Audi’s claimed 417 km. Our Turracher Höhe hotel provided free charging, and one of Germany’s 400-strong, 150kW charging stations give 80 percent charge in 30 minutes. By the time the e-tron goes on sale in Australia next year at around $140,000, Audi predicts range anxiety will not be an issue.

Audi planned a replacement for the Quattro, but after the sales failure of the 1991 S2 coupe, based on the B4 80, the idea of a standalone and authentic Quattro replacement RS2 coupe died. At the 2010 Paris show, Audi unveiled a Quattro concept to celebrate the 30th anniversary of the original. There was talk of a small production run of up to 500 cars, but the project was abandoned in 2012.

Despite a string of wonderfully innovative, technology-driven and beautifully styled Audis over the decades since, Ingolstadt seems to have decided it’s best to leave the original Quattro as a tribute to a team of dedicated engineers who created the car that shook the establishment to its core and set Audi on its path to greatness.