The new cars rolling onto Australian roads have never been safer yet somehow the road toll is still rising across the country.

A government plan to halve deaths by 2030 is in ashes and there is no indication on why the National Road Safety Strategy – adopted with considerable fanfare in 2021 – is failing so miserably.

Is it the roads, is it the drivers, is it the cars, is it distraction, or drugs, or fatigue, or too much speeding?

How can it be so bad when 5-Star ANCAP safety ratings are considered the bare minimum for new-car acceptance in showrooms?

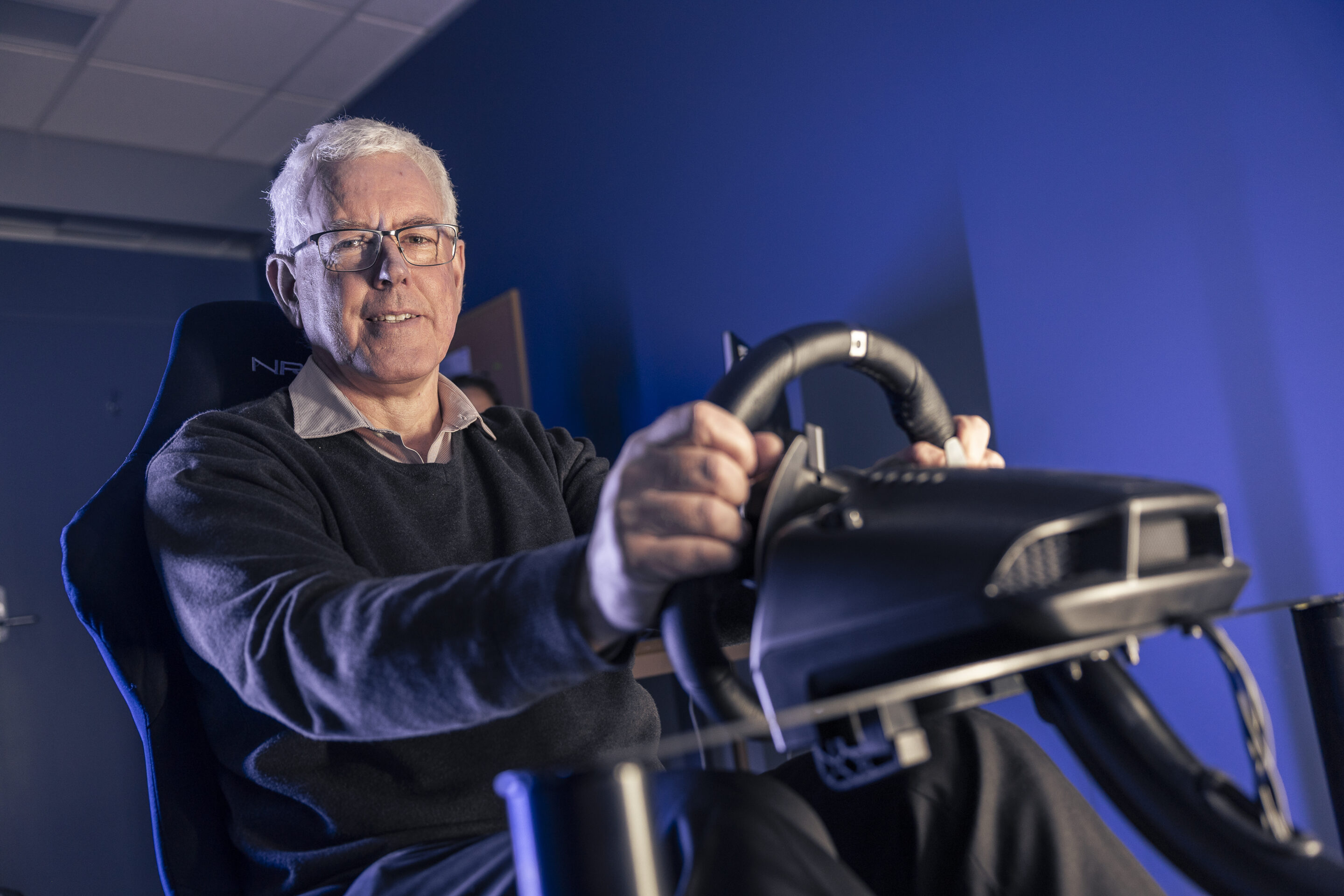

“We’re pretending we can still live in the 1950s. And it’s not working,” Professor Stuart Newstead tells Wheels.

“If I had a magic wand I would wind our transport and urban planning process back 70 years and start again. The systems are failing for both mobility and motoring. People are not trying to have major crashes. They might just make a genuine mistake.”

What would Professor Newstead know? He’s not a famous racing driver, or a new-car engineer, a policeman or an ambulance officer.

But he knows more than most about road safety and not just the ‘horror crash’ headlines that inevitably dominate the media coverage of holiday road carnage.

He has more than 30 years of experience at the crucible of Australian road safety, the Accident

Research Centre located at Monash University in Melbourne (MUARC).

It’s an organisation that does all sorts of safety research, even on accidents around the home and worksites, but is known best in the car world for its road safety research including the annual Used-Car Safety Ratings. These might not receive the coverage and support of the latest ANCAP crash-test scores, but they are much more useful for people who go shopping for their next car on the second-hand scene.

It’s about applying scientific research to real-world crashes, deaths and injuries, work begun at MUARC in the early 1990s by Professor Max Cameron under MUARC’s founding director Peter Vulcan, a pioneer of road safety science and vehicle safety regulation in Australia.

Newstead admits he spends a lot of work time with his head buried in spreadsheets and data documents, but those resources are not just ones and zeroes. Instead, his research tools are a genuine reflection of what’s happening on Australian roads.

Creation of the ratings means compiling and comparing reports from more than nine million vehicles involved in police-reported crashes in Australia and New Zealand from 1987, then translating them into a star rating between zero and five. The results have grown to produce comparative results for more than 500 vehicles covering almost everything on Australian roads.

Newstead is just finalising work on the ratings for 2025 and, without giving too much away, he has one rock-solid prediction.

“None of the utes will achieve 5 Stars. They are big, they are heavy, they are stiff, and they are incredibly bad for ‘partner’ protection,” he says.

He is talking about the impact of utes on other vehicles and occupants, particularly smaller and lighter cars. As the director of MUARC, he leads a team of around 40 people who work on a variety of road safety research programs. He’s been there for more than 33 years, after completing a full suite of university courses to claim a Bachelor of Science with honours, a Master of Science and Doctorate majoring in mathematical statistics with minors in physics and applied mathematics.

“I also completed half a mechanical engineering degree but decided I was more interested in science,” he says.

He’s not only hugely qualified, therefore, but now also has vast experience in the car world, although he did not start down that road.

“Whilst I spent the early stages of my career in disease epidemic modelling, I pivoted to road safety

research when I joined MUARC and quickly developed a specialist focus in vehicle safety and in particular measurement of vehicle safety performance from real world data. Scientific evidence is absolutely critical.”

And even though he is a numbers man, he is also a car guy.

“I’ve always had an interest in cars and driving since I was young. My father was into his vehicles and, as a company sales representative, brought home a new vehicle every couple of years which was always an occasion.

“I was into the car club scene for quite a few years. I still love working on my cars now when I have time.

“I am also a bit of a motorsport tragic, particularly Australian touring car racing. My interest is as much in the technology involved as the racing and since joining MUARC, the systems

involved in making racing safe. “

Now 57 and married with two adult children, his daily driving choice might come as a surprise. No, it’s not a Volvo…

“I drive a VF SV6 Holden Commodore Sportwagon. It’s a safe and practical car that was excellent value for money and served the needs of a growing family for many years,” he says.

“It’s fantastic to drive, super reliable and reasonably economical, particularly on long country runs to visit family interstate. I was also proud to support the local vehicle manufacturing industry and all the dedicated people who worked in it.”

He’s also familiar with the work that went into the last of the homegrown Holdens.

“MUARC did a lot of work with Holden at its peak and the passion of its engineers for safety was outstanding.”

He admits he could have moved to something newer and tastier, but his safety-first approach with his children meant they got priority.

“I have helped both my children get into safe cars when they first started driving. I had no hesitation in doing what I could to make sure my children are safe in their early driving careers.”

He taught them to drive but, thanks to his research and experience, is not advocating for advanced driver training.

“It’s quite an interesting skill, driving. You need to have confidence and skill to do it well, but you also need to be incredibly risk averse as well. Even the best and most experienced driver can make a mistake.

“The cognitive load in driving is enormous. For at least the first couple of years we know young drivers are not up to the tasks and we put them on the road hoping they survive.

“The common view in road safety is ‘It’s the drivers’ fault’. But we have not found a driver training system that stops people making errors. It does not exist.

“An ideal driver licensing system would ensure young drivers have experience in all situations in all conditions, and then slowly test their skills in more and more demanding situations as they transition to solo driving. But that’s time consuming and expensive.”

So where should people look for answers on the road safety front?

“The problems we have are in how our country has developed. We haven’t developed around the modern concept of mobility. We’re dealing with a legacy system that is not fit for purpose, and trying to put band-aids on it.”

Newstead contrasts the congestion in big cities with the under-developed situation in the countryside, and the work needed to improve safety.

“It comes back to the overall environment. Cities need much greater investment in public transport. The regional network is incredibly poor and incredibly dangerous. So it’s not only the maintenance of roads, it’s the fundamental design of the system.”

Newstead also highlights society’s attitude to road trauma of all kinds.

“Unfortunately, road deaths are still too normalised as an inevitable factor of life,” he observes. “You have to treat it like a public health problem. People are horrified when a plane crash is reported, yet in 2024 just under 300 people died in air crashes internationally. This compares to over 1.2 million who died in road crashes with around 1300 fatalities in Australia alone.”

Some of that starts with car choices. So, once again, he goes back to the numbers and the MUARC

research. More than 500 vehicles are listed in the Used Car Safety Ratings, 113 currently have a 5-Star rating with more than 50 also upgraded to the ‘Safer Pick’ status. But vehicle choice alone does not ensure safety.

“People buy a 5-Star car and think it can protect them in all situations. They get over-confident.”

The MUARC ratings also track the improvement in vehicle safety, with the average risk of death or serious injury for drivers in 2022 models reduced by 36 per cent compared with those manufactured in 2002.

“The underlying risk is reducing. But you need to reduce the risk faster than the population is growing to lower the road toll.”

Newstead is quick to highlight the poor choices being made by many people.

“There are things not addressed around the fleet mix. Particularly the growing size and different dimension of vehicles,” he says, talking about the size and weight of utes and large family SUVs.

Newstead also says road design and maintenance in Australia is a major problem.

“It’s an awkward conversation. Vehicle safety has improved incredibly, but the support we give vehicles to be safe on the road is not good. Crash avoidance technologies are seen as the next great hope. But they are still not well supported. Look at lane-keep assist – we don’t have the road infrastructure everywhere for it to work well which makes the technology frustrating or ineffective.

“We need to make all roads more like the Hume Highway. We’ve made it incredibly safe. It should be the model for all major country roads.”

But, in the end, Newstead says people are still an important factor.

“Driving today is immeasurably safer than it was 50 or 60 years ago. But we have a very bad attitude in Australia, in terms of sharing the road network with other people. Some people think it’s a competition. And it’s become more prevalent since the pandemic, because people are more inwardly focussed.

“Everybody drives. Everyone thinks they know how to solve the road safety problem. And most of it is complete bunkum.

“Safe road use is not a race. It’s not a competition. Safe roads come from all working together to look after each other and comply with the rules.”

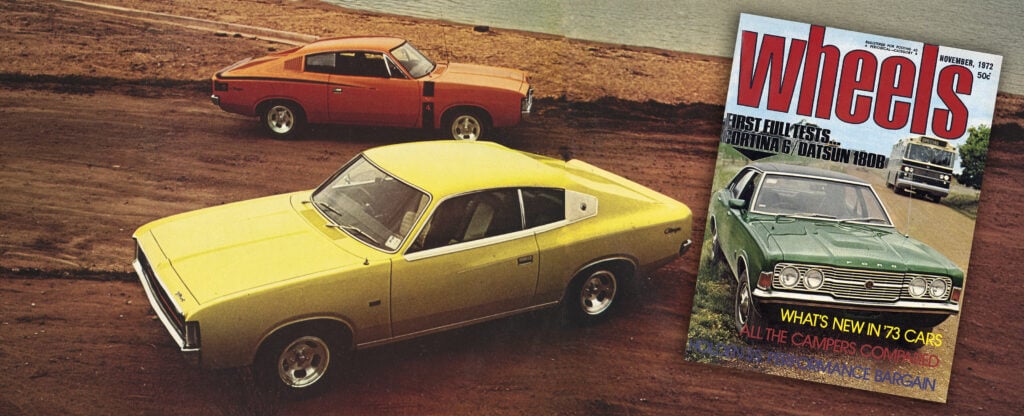

The article originally appeared in the November 2025 issue of Wheels. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesThe Wheels Interview: How Bernie Quinn's Premcar solves problems for some of Australia's most popular makes

Bernie Quinn was an underperforming, self-confessed ‘battler’ before he found his feet as an engineer at Ford. These days he’s the CEO of Premcar, a company he has built up with a former colleague to create uniquely Australian answers to a variety of automotive questions.

-

Features

FeaturesThe Wheels Interview: Brian Tanti, the craftsman who managed Lindsay Fox's car collection

He calls himself a ‘coach-builder’, suggesting a throwback to earlier times, but Melbourne’s Brian Tanti is so much more and at the forefront of a revival in automotive craftsmanship.