You’re forgiven for not spending a great deal of time studying the ins and outs of vehicle emissions testing.

It’s not the world’s most exhilarating topic, particularly as we’re betting most MOTOR readers are happy to sacrifice a little (or a lot, in some cases) fuel consumption for more power and performance. However, the regulatory net is closing and will force major mechanical changes to the next generation of performance cars and beyond.

Let’s start with where we’ve been. The New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) was introduced in 1970 to assess passenger car fuel economy and emissions. There are other tests, such as that conducted by the Environmental Protection Agency in the US, but the NEDC is relevant in Australia because it forms the basis for fuel economy and emissions testing under Australian Design Rule 79/04.

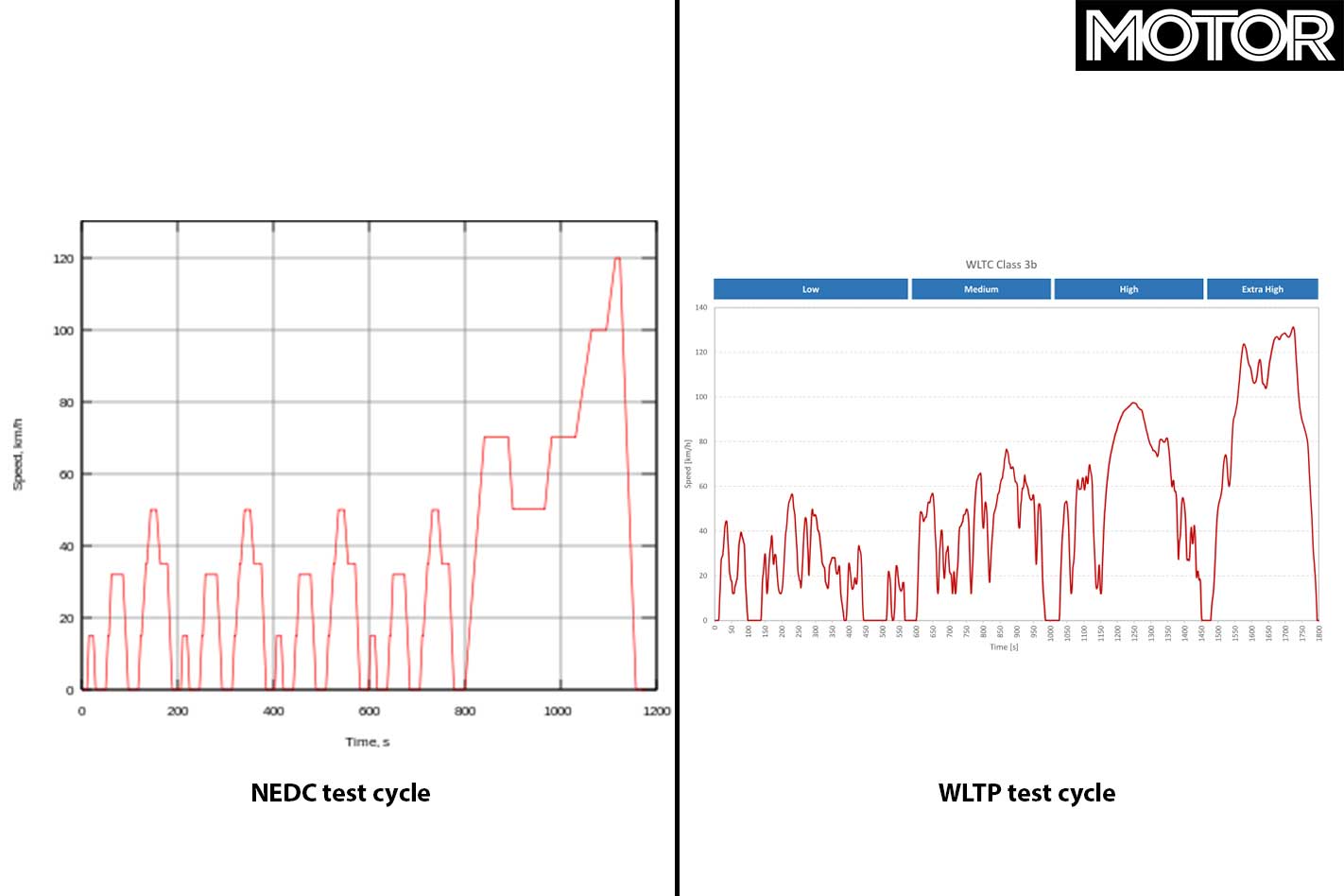

The NEDC consists of an urban driving cycle repeated four times consecutively (the ‘urban’ economy figure) followed by an extra-urban cycle (the ‘highway’ figure), which are then combined.

If you’ve ever wondered why your car’s claimed economy is difficult to achieve, it’s because the NEDC is not in any way representative of real-world driving.

We won’t bore you with the nitty-gritty details, but essentially the entire test is spent at idle, cruising, or gently accelerating and decelerating at a rate that even your grandmother would call leisurely. The most enthusiastic acceleration is during the initial 0-15km/h phase, which is required to take four seconds, the equivalent of 0-100km/h in 26.6sec.

Is it any wonder that modern cars are predominantly powered by low-capacity, highly boosted engines with stop-start systems and as many gears as possible? Thus equipped, the NEDC can be completed off-boost at low rpm and with the engine off for a large proportion of the test.

The NEDC has rightly been criticised for its lack of real-world correlation and has now been replaced by the Worldwide Harmonized Light Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP), which came into force in Europe from September 1, 2018.

Again, we’ll save you the specifics, but WLTP is a longer test split into four cycles (low, medium, high and extra-high speed) that, crucially, requires much more dynamic driving. The acceleration and deceleration events are still unrealistically slow, but there are more of them.

In layman’s terms, WLTP economy and emissions figures will be closer to those of the real world. For example, the VW Up GTI’s figures of 5.76L/100km and 110g/km CO2 increased to 6.73L/100km and 127-129g/km CO2 under WLTP.

This is good news for customer knowledge, but bad news for manufacturers. For some, particularly the Volkswagen Group, it has caused chaos. Porsche suspended orders for its entire model range, Audi suspended the SQ5, the VW Golf GTI was removed from sale, and the Golf R lost 7kW. And that’s just some of the VAG impact.

Elsewhere, BMW killed the M3 and the base M2 early, Jaguar removed its petrol XJs from sale and slimmed down its XF range, and Peugeot suspended sale of its 308 GTi 270.

The problem goes beyond just greater fuel use and emissions, though that’s bad enough when by 2021 a manufacturer’s fleet average emissions must be below 95g/km CO2. The real issue is that most of the ‘tricks’ used by manufacturers for the NEDC don’t translate to the WLTP. This isn’t Dieselgate-style cheating, but tuning designed to achieve the best possible results.

Many cars use 1:1 air-fuel ratios (known as stoichiometric) at light loads to improve economy only to add fuel to control temperatures and protect components such as the turbocharger under heavy loads.

This is where it gets tricky for future performance cars, particularly as it’s likely that the as-yet-unconfirmed Euro7 emissions regulations will force manufacturers to use stoichiometric air-fuel ratios at all times, ending the practice of using fuel as a cooling agent.

This gives manufacturers a choice: reduce power, make components able to withstand higher temperatures, or introduce technology like hybrid turbochargers, water injection or variable-compression. However, the most likely outcome is that these regulations will simply accelerate the development of pure-electric cars.