Supercars tend not to have much in the way of shelf life.

If your currency is to shock and amaze, then it stands to reason that these attributes fatigue quickly. Problem is, nobody seemed to have informed Lamborghini. The Countach remained in production for 16 years, its introduction at the 1971 Geneva Motor Show was closer to the era of the Ford Model T than it is to today.

Yet even now it has the ability to snap necks as it passes. If anything, its form factor appears even more extreme in a world of bloated, risk-averse designs. The Countach is tiny, considerably shorter than a Toyota 86, its alien blending of flat planes and muscular curves a design language that has been lost to time.

Styling can be contentious. It’s impossible to consider the Countach without first placing the car in some sort of frame of reference, and that frame of reference is called the Miura. This remarkable car established the company’s reputation for outrageous styling. Marcello Gandini claimed credit for the work, but there are many who believe the Miura’s proportions came from Giorgetto Giugiaro’s pen with the young Gandini merely filling in some of the final details for the end result.

The Miura was neither the first supercar – the Mercedes-Benz 300SLR has a better claim there – nor the first mid-engined coupe, with the Matra Djet, the Porsche 904 Carrera GTS and the De Tomaso Vallelunga amongst others already in production before the slinky Lamborghini was unveiled. Nevertheless, the Miura taught a company that had been in business just 29 months a valuable lesson. Extremity sells.

It was also clear to Ferruccio Lamborghini that if the company was to make the next step on from the Miura, it needed to change its processes. Prior to the Countach, Lamborghinis had been built at different locations according to a very well-trodden tradition. External coachbuilders fabricated the bodies, while the technical underpinnings were built in-house at the tiny Sant’Agata Bolognese plant. Carrozzeria Bertone built the Miura body in Turin and Marchesi fabricated the chassis in Modena.

When the original factory was completed in 1966, it measured a mere 12,000 sq m, and featured two production lines. One was dedicated to engines and mechanical components, the other for vehicle final assembly. That changed in October 1968, when Lamborghini built three new factory buildings. Today, the factory is a sprawl of some 346,000 sq m, but the original Countach production line (Linea Montaggio N.1 Countach) is still there, with Revueltos now passing down it.

If the Countach required revolution to build, it also required a seismic shift in design ethos. As Gandini stated in a 2021 interview with Forbes, “The original mechanical setting of the Miura conditioned its shape while with the Countach it was the opposite: the shape conditioned the mechanics. Both were the result of a collaboration and a similar way of thinking between me and the people in charge of the mechanics.”

Chief Engineer Paolo Stanzani oversaw the development of a complex semi-monocoque spaceframe for the first LP500 prototype, developed in secret as the innocuous sounding Project LP112. Created from box-section steel, Stanzani was tasked with righting many of the Miura’s shortcomings in terms of weight distribution, aerodynamic stability and maintenance access. The engine was to be an enlarged version of the Bizzarrini V12, but there’s no evidence that a fully functional five-litre V12 was ever fitted to the car. As a result, the rest of the work progressed quickly. From a project start in early 1970, a Countach LP500 prototype was readied for the Geneva Show in March 1971.

We like to think that the Countach shook the automotive world in Geneva, but many were more than a little sceptical of Lamborghini’s aspirations. Peter Robinson went on to say what many were thinking. “When the first photographs and words about the Countach arrived in our office in 1971 we were, despite the evidence of the Miura to the contrary, convinced the Countach was just another show car,

destined to make a few public appearances before being consigned to the museum as an impractical fantasy,” he recalls. “It was, we felt, too bizarre, too extravagant to be taken seriously.”

That yellow LP500 prototype was subsequently used as a test mule and was crash tested in March 1974 in order to gain type approval. In hindsight, that was a bit naughty of Lamborghini, as the next car to be built, chassis 1120001 – originally red at the 1973 Geneva Motor Show and which is now green and living in the Lamborghini museum – was a very different creature. Marchesi swapped the original’s box-section steel for round tubing which, while more complex to fabricate, was far stronger and cut weight from 107 to 90kg. Bertone fashioned 1.2mm-thick aluminium-alloy body panels rather than steel, further cutting weight from the original show car. This vehicle finessed many of the details to feature on the first production model.

Brake cooling ducts were added to the nose section, while the complicated V-type windscreen wipers were swapped for a simpler single blade. When the team was happy with the development program, the car was sent to Giovanni Raniero’s workshop in Orbassano on the outskirts of Turin, where it was used to create the Elmwood master model for all future production Countach models, fully built in-house at Sant’Agata.

Amazingly, chassis 112001 appeared on, of all things, a Yahoo auction in 2000, having languished in a Swiss barn for years. Test driver Valentino Balboni and engineer Giorgio Gamberini spotted the Rosso overspray peeking out below the Verde paintwork, realised what they were looking at and bought the

oldest surviving Countach for Lamborghini.

The first proper ‘production’ Countach was the yellow LP400 on display at the Geneva Show in 1974, and even that was a close-run thing. The car was still being finished at 2:30am on the day of the show’s opening. There was quite a to-do list to attend to in order to turn chassis 1120001 into a car that was ready for paying punters. The biggest change was from the planned five-litre V12 of the LP500 prototype to the smaller 3929cc unit, largely for durability reasons, as the bored and stroked version had grenaded itself on the test bench during initial testing.

The LP400 had the brake cooling ducts now integrated into the front wing sheetmetal, but the most obvious exterior change were the side windows. Lamborghini broke more than 20 panes of glass trying to get them to conform to the curved track of the Countach’s extreme tumblehome, and instead opted for a three-pane layout, where the lower pane could be lowered. The NACA ducts were painted satin black, as was the front grille area (from silver) and the aluminium body panels were beefed up to 1.5mm gauge to make them a bit more durable.

The cabin came in for some attention too, with a set of eight gauges supplied by US-firm Stewart Warner, while the dashtop was trimmed in dark suede after it was discovered that reflections made visibility a challenge. The door sills were altered and the position of the handbrake shifted forwards. These LP400 models are the most valuable and purest of all Countach models, with the auction record being a 1974 example sold by Goodings at Pebble Beach in August 2014 for $1.87m (AUD$2.85m). Since then, values have softened off a little, but now seem to be back on the rise.

Demand for the LP400 wasn’t a problem for Lamborghini. Finding the funds to keep the business afloat most certainly was, a theme that would persist on and off until Audi acquired the company in 1998. Enter Walter Wolf. The Canadian businessman was a repeat customer, a backer of Williams F1 and would go on to form his own team in 1977, with Jody Scheckter scoring three race wins. Wolf had some very firm ideas about his 1975 Countach.

In came a five-litre V12, along with the big tele-dial Campagnolo alloys from the Bravo Prototype, shod in massive (345/25R15 at the rear) Pirelli P7 tyres to replace the LP400’s Michelin XWXs. To cater for the wider wheels, the Wolf Countach got fender flares, and a massive rear aerofoil as fitted. Wolf was so taken with the aesthetic that he bought a second car, this one with the 3.9-litre engine. Lamborghini clearly thought that the more aggressive styling direction had some legs too, as the Wolf car would go on to inform the design direction of the 1978 LP400 S model, featuring the 257kW 3939cc V12.

These cars were delivered in three discrete series. The first 50 cars were Series One versions and were most faithful to that Walter Wolf look. They featured the same Campagnolo alloys but with body-coloured wheelarch extensions and optional, but famously non-functional, rear wing. These Countach models were the so-called ‘low body’, with lower suspension. The Series Two cars were largely similar, with 105 cars built, identifiable by their smooth finish dished alloys. Finally, from chassis number 1121312 on were the Series Three versions, which raised the suspension, and allowed for an additional three centimetres of headroom in the cabin. These were the final 82 cars to wear the LP400S badge.

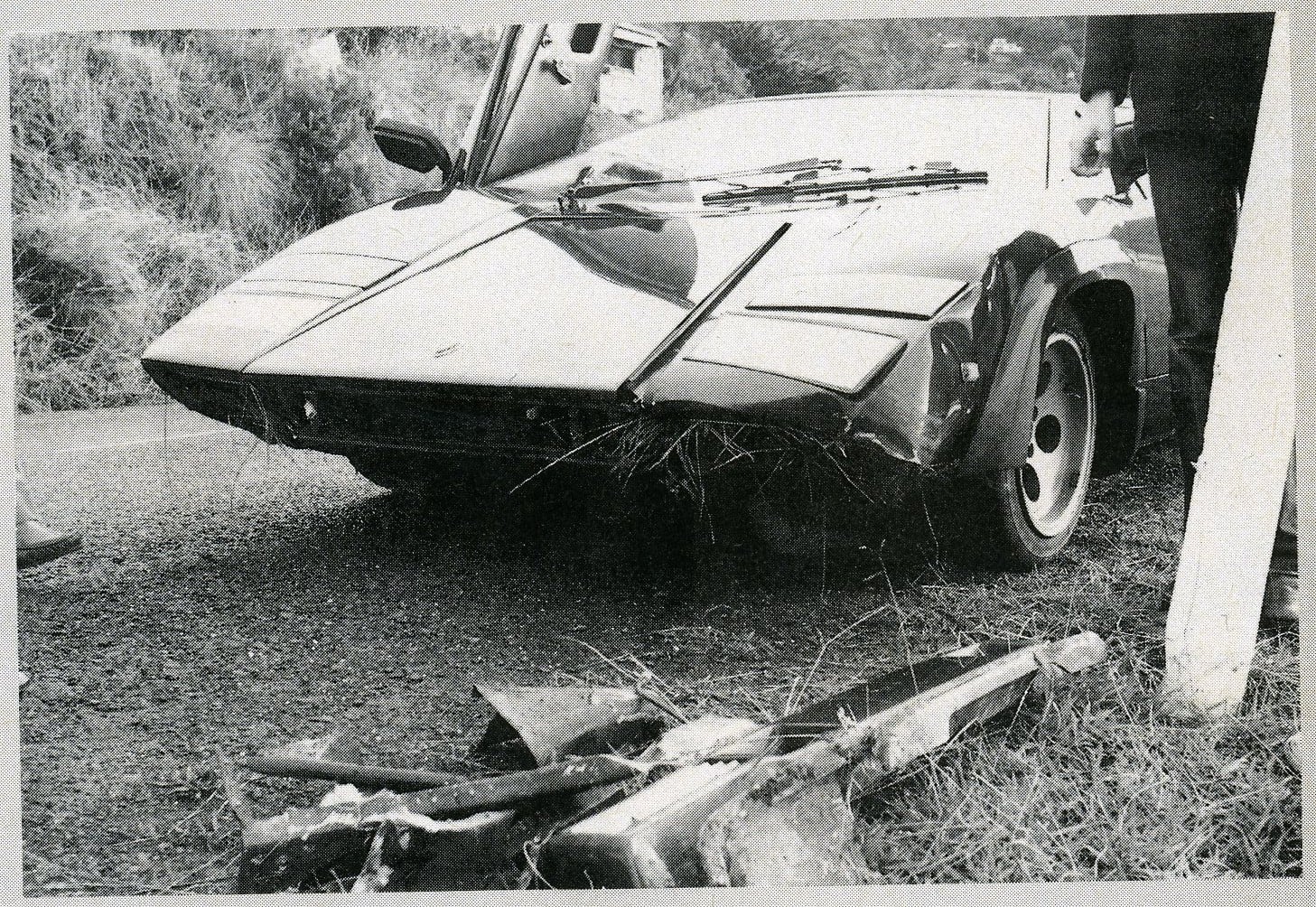

It took until 1981, a decade after the Countach was first announced, before a Wheels staffer got to drive one. Peter Robinson drove an LP400 S2 on a wet Great Ocean Road during an eventful journey, where one of the two cars returned looking distinctly the worse for wear. “We came to realise that the Countach requires a firm grip, a strong hand and plenty of muscle,” Robbo noted. “Treat it softly, casually or timidly and it will laugh at you, and you get out wondering what all the fuss was about, though in truth the car will have frightened you away. But if you are demanding, brutal, aggressive then you will come to understand the Countach and, if your driving is up to the high standard required, then it will give you vast pleasure at a level few other cars can hope to attain.”

In that same November 1981 issue, Steve Cropley visited the factory to discuss how the company had just been rescued from bankruptcy by 24-year old Swiss businessman Patrick Mimram. Lamborghini had been put into effective receivership in August 1978. The price he paid for the company? A mere $4 million. It’s now estimated to be worth over $40 billion. Inflation aside, that’s a 10,000-fold increase. Let’s just say that corporate governance has improved in the interim.

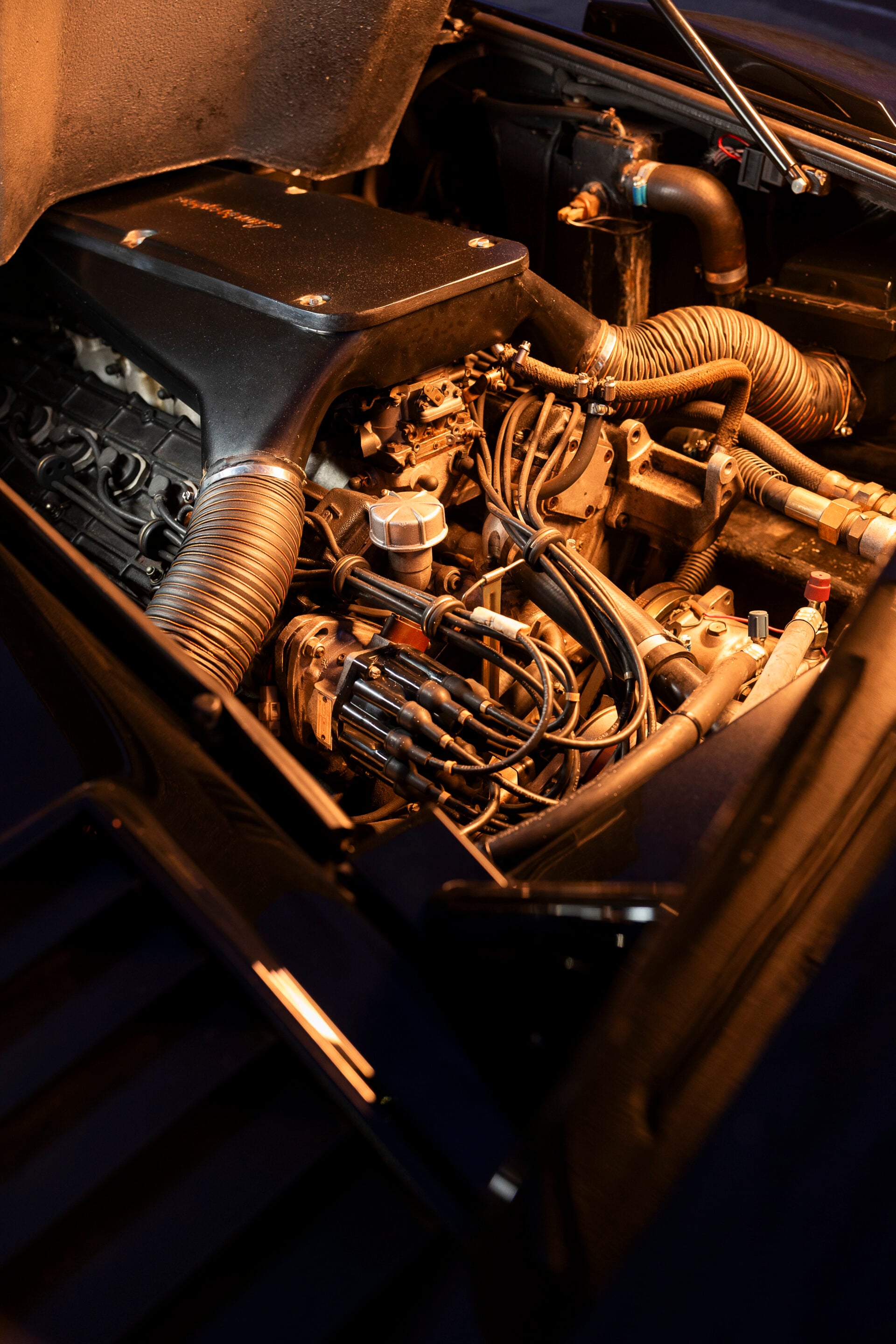

The Countach finally got a larger capacity engine with the 1982 Countach LP500 S (also badged as the LP5000S in some markets). With its bore lifted from 82 to 85.5mm and stroke lengthened from 62mm to 69mm for a swept capacity of 4754cc, the 4.8-litre V12 was less stressed than the old 3.9, with compression dropped from 10.5:1 to 9.2:1. While the peak power figure was an identical 280kW it arrived at 7000rpm rather than 8000rpm, while peak torque lifted from 386Nm at 5000rpm to a more tractable 409Nm at 4500rpm. The engine update was much needed. Ferrari was rumoured to be readying a replacement for its aged BB 512i and in 1984 Ferrari announced the Testarossa, which featured a class-best 287kW from its flat-12.

Maranello’s sense of superiority was not to last. Lamborghini’s riposte was the car you see on these pages, the Countach LP5000 QV. As the name suggests it adopted a four-valve, or quattrovalvole, cylinder head. Capacity grew to 5167cc, with power stepping up to a massive 335kW at 7000rpm and 500Nm at 5200rpm. The compression was lowered again, this time to 8:1. The QV was, for many, the ultimate Countach iteration and the poster car for a whole generation of kids. Robbo was again the man on the spot in a Wheels test in July 1988, summarising his drive with the words “take charge and you will have discovered why, after 17 years, it is unsurpassed.” Incidentally, that issue of the magazine also featured the car that would finally depose the Countach as the reigning monarch of Italian supercars; the Ferrari F40.

While most media outlets dismissed Lamborghini’s top speed claims as being distinctly fanciful, Peter Dron, the editor of UK magazine Fast Lane was invited to Sant’Agata in 1986 to witness for himself the speed of the QV. With F1 hotshoe Pierluigi Martini at the wheel, the Countach raced through the flying kilometre in 11.46 seconds, confirming an average speed of 314.1km/h (195.1mph). Dron claimed to have seen 325km/h (201.9mph) at one point on the speedo. It seemed the QV really could live up to the hype. Some years later, test driver Valentino Balboni admitted that the wingless car wasn’t exactly customer standard, with a non-standard airbox giving the car a boost in top-end power to combat its 0.42Cd drag coefficient.

When German title Sport Auto put the Countach QV up against the Ferrari Testarossa in June 1987, it discovered that the 1490kg Lamborghini was significantly quicker out of the blocks, registering 0-100km/h in 4.8 seconds versus the 1630kg Ferrari’s 5.6-second showing. Keeping the throttle mashed through 200km/h saw the QV stop the clock at 17 seconds, with the Testarossa registering 18.8 seconds. Yet on a lap of their reference circuit, the Hockenheim Short Course, the two were almost inseparable, the Testarossa scoring pole with a 1m19.9sec lap and the Countach just two-tenths in arrears, crossing the line in 1min20.1sec. The Ferrari was more stable in the higher speed corners, with the Lamborghini clawing back an advantage accelerating out of tighter bends.

The 1986 QV you see here was originally a UK car finished in red, and was shipped to Australia by its current owner 20 years ago. Feeling that red was a colour more readily associated with the mob down the road, its owner had it painted black, with the silver OZ alloys in this beautiful satin gold. At the same time, it was treated to a meticulous nut and bolt restoration. The smoked lenses on the driving lights are per the owner’s preference, but he’s kept the clear originals. It’s covered a healthy 91,300km so it’s certainly no garage queen and is for sale at Young Timers Garage.

If the QV represented peak aggression, its successor, the 25th Anniversario was perhaps the moment that the Countach entered its Elvis in Vegas era. Announced in 1988 to mark 25 years of Lamborghini as a company, it features straked side skirts that are a slightly lame riff on the Testarossa’s styling signature, a raised nose, heavier bumpers and a rear light cluster that lost all of the drama and purity of the original and instantly recognisable shape. The styling work was done by in-house composites expert Horacio Pagani (yes, him) who was handed a thankless brief. Nevertheless, following his work on the Countach Evoluzione design study, the Anniversary was treated to carbon fibre panels for the bonnet and engine cover.

It’s a shame the Chrysler-developed Anniversary’s aesthetic had jumped the shark, as the mechanical package was excellent, making it the best Countach to drive. The tyres were the much-improved Pirelli P Zero, running on two-piece forged OZ alloys, while the suspension was still the same rose-jointed setup with double wishbones front and rear with Koni dampers.

The mechanical reliability of the engine was improved, with a redesigned engine bay easing access to ancillaries and helping cut servicing costs. Taller drivers could specify a fixed back sports seat instead of the standard electric items as this yielded a few centimetres of extra headroom. The electric windows, a redesigned HVAC interface and a redesigned gear shifter were all features that would carry over into the Countach successor, the Diablo. Despite being on sale for just 19 months, the Anniversary was the biggest selling Countach variant, thanks to its success as a fully federalised car for the US market.

The Diablo arrived in 1990 and started a pattern of ever bigger, heavier and more mechanically complex V12 Lamborghini models. By today’s standards, the Countach seems a very small and very simple car, shrink wrapped around its engine and transmission in the way an A-10 Thunderbolt II jet is built around its massive GAU-8 Gatling cannon. Fire up that V12 though, and any suspicion that age has mellowed its ferocity is instantly dispelled. There’s no ABS, no traction control, no airbags, no stability control – it’s just you, that howling engine and four contact patches.

For years undervalued by collectors, the Countach has recovered. Perhaps it’s the realisation of this car’s rarity, with only 1998 customer cars ever built over 17 years, with fewer than 1600 remaining today.

The Countach is an icon of late 20th century cars. Revisionists will try to tell you that it was never that good, or that it was a car that drove Lamborghini to the brink of ruin, or that the Ferrari Berlinetta Boxer was superior but they’d be wrong. I believe one thing is unarguable. No other car before or since has ever captivated so many people and seduced them with the magic of what a car could do, could be and could represent. To many, Lamborghini sold a dream. To the few, it sold something even more special.

What Goes Around…

Read Peter Robinson’s 1981 test of the Countach S on the Great Ocean Road and it’s clear that he treated the car and the tricky conditions with a considerable measure of respect. Unfortunately, Wheels dep-ed Bob Murray wasn’t quite so circumspect in the other Countach and managed to remodel the nose of one car after having a spin. Robbo managed to persuade the MD not to fire Murray, and the favour was returned years later when Bob hired Robinson as European editor for Autocar.

Specs

| Model | Lamborghini Countach LP5000 QV |

|---|---|

| Engine | 5167cc V12, DOHC, 48v |

| Power | 335kW @ 7000rpm |

| Torque | 500Nm @ 5200rpm |

| Transmission | 5-speed manual |

| L/W/H/WB | 4240/2000/1070/2473mm |

| Fuel tank | 2x50L |

| Kerb weight | 1490kg |

| 0-100km/h | 4.8sec |

| Price (now) | c.$1.7m |

Thanks to Young Timers Garage and Theo George. This article first appeared in the January 2026 issue of Wheels. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesModern Classic: Jaguar XJ220 – underrated or misunderstood?

The world’s most underrated supercar or a case study in confused development? The truth, as always, is a little more nuanced

-

Features

FeaturesModern Classic: Lancia Delta HF Integrale, the ultimate rally car

It was never officially sold in Australia but as it’s the basis for the most successful rally car of all time, the Delta Integrale more than earns a pass as a Wheels' Modern Classic.