Call it the law of unintended consequences.

This is the story of how the legendary Lancia Delta HF Integrale came into being, but before we get there, it’s worth reminding ourselves how and why that car earned such iconic status.

When Lancia set out to build its no-holds-barred 1980s Group B rally weapon in the shape of the Delta S4, it never quite met expectations. Despite this twincharged mid-engined silhouette car’s fearsome 368kW power output, it was beaten by Peugeot and Audi in the 1985 season and by the dominant Peugeot 205 T16 again in 1986.

Henri Toivonen’s fatal crash at the Portuguese round of the world rally championship in 1986 put an end to Group B. For the format that was to succeed it, Group S, Lancia had already developed an advanced prototype, the ECV (Experimental Composite Vehicle). The apex of rallying took a step back in terms of power and technology, adopting the Group A ruleset, which required an all-wheel drive production car base.

Fortunately for Lancia, it had exactly that. The Delta hatch was introduced in 1979, a crisp Giugiaro-penned five-door that featured a version of the existing Fiat Ritmo’s chassis, plugging a gap below the Beta in Lancia’s line-up that had previously been served by the Fulvia Berlina. Saab pitched in with the development, helping with rustproofing, the ventilation system, the tailgate design and the split-folding rear seats.

In return, it would get a badge-engineered version for Nordic markets, dubbed the Saab-Lancia 600, which wasn’t particularly successful and was quietly withdrawn in 1982, just two years after launch. Elsewhere, the Delta’s reception was a good deal warmer, having captured the 1980 European Car of the Year crown. However, the company was slow to realise quite what it had on its hands as the basis for a rally car.

After all, Lancia had already ventured down the wrong route once in its Group B challenge. Desiring a latter-day Stratos, it developed the rear-drive Rally 037 in conjunction with Pininfarina, Dallara and Abarth when all of its competitors accepted that all-wheel drive was the only viable way forward. Amazingly, the 037 did win the 1983 manufacturers’ world title, at the hands of two rallying legends: Walter Röhrl and Markku Alén. It would prove the last time a rear-drive car would ever claim rallying’s most prestigious award.

Its replacement, the Delta S4, was perhaps the most extreme special stage car to enter Group B. Work began on this project in April 1983, with initial tests showing that it was already a massive four seconds faster than the 037 around the 2.2km La Mandria test track. The Delta S4 was unveiled in December 1984, with homologation granted on November 1, 1985. We know its rallying palmarès.

Hindsight shows that the Delta was a smarter engineering concept than the 205 T16, but the Peugeot was a better technical execution in practice. That’s as maybe, but FISA’s knee-jerk reaction to Toivonen’s crash in the Delta S4 Portugal had the unintended effect of suddenly putting Lancia in the box seat.

Adapting the 1986 Delta HF 4WD road car to the new Group A rules wasn’t particularly difficult, and Lancia’s task was made easier by Peugeot dipping out of the championship. The French were furious at the decision to ditch Group B, stating publicly that they would never build a Group A racer since the ruleset made no sense to them. Instead, Peugeot directed efforts into the 905 sports car prototype racer to enter in the Endurance Racing World Championship. Audi also found itself at a competitive disadvantage to the flyweight Delta in an era where power was capped at a notional 300bhp (224kW) by a 34mm turbo restrictor and there was no minimum weight limit.

With the likes of Markku Alén, Miki Biasion, Bruno Saby and that year’s world champion, Juha Kankkunen, at the wheel, Lancia romped to the 1987 title, scoring 140 points with runner-up Audi a long way distant on 80. The following season opened with the Delta HF 4WD rally car again looking hard to beat, winning the first two stages in Monte Carlo and Sweden, but Lancia had something even better waiting in the wings.

For the Portuguese event in March, the Italians rolled out the Delta HF Integrale, arriving on the gravel a full six months before the production version would be launched to the public. Lancia won every round of the 1988 World Championship bar Corsica, where the Integrale finished second. Miki Biasion claimed the driver’s crown and, in the form of the Integrale, a rallying dynasty was born. Lancia would go on to win rallying’s top award for manufacturers every year up to and including 1992. The Delta’s rallying dominance saw its sales leap by 42 per cent in its home market in the first half of 1987 and helped burnish the appeal of the Integrale road cars.

These started with the Integrale 8v. Compared to the outgoing Delta HF 4WD, the Integrale initially didn’t seem night-and-day different. The engine was a carryover item, and could still trace its genesis back to the Aurelio Lampredi-designed Fiat twin-cam unit. For the Integrale, it was fitted with new valves, valve seats and water pump. A bigger air cleaner, cooling fan and larger radiators were fitted too, alongside a larger capacity Garrett T3 turbocharger.

The Integrale was a bucket list car for the rally team’s engineers. They wanted more tuning headroom, less weight, bigger brakes, a stronger chassis and suspension and a wider track. They got the lot. Only ever sold in left-hand drive form, the ’Grale never officially came to Australia, but that didn’t stop it being a target for importers looking to sidestep the red tape.

It also means that it’s one of the few modern classics we’ve covered in this series that was never treated to a Wheels drive story.

It did figure at number 13 on Peter Robinson’s list of the 50 Greatest Cars Of All Time, in the July 2011 issue of the magazine, and that’s quite the recommendation. Robbo praised “the urgency of its responses and an ability to go exactly where it was pointed at speeds that staggered the senses,” finishing up with, “I still want one.” Interestingly, a number of other cars that existed within the Delta’s competition periphery were also featured in that rundown, including the Peugeot 205 GTI, the Audi ur-Quattro and the Toyota Celica, so perhaps the Eighties really were the era of peak rally car.

Given that many car model lines are facelifted at three years old and replaced at seven, it’s unusual that the Integrale 8v first appeared when the Delta shape was already eight years old. It’s also instructive to appreciate that when pitched against the ur-Quattro, the Integrale offered a similar level of performance at almost half the price.

Drive the two rivals back to back and the Integrale feels more alive, with more communicative steering and crisper turn-in. The Audi is a more civilised thing, ultimately quicker, and has more in the way of presence. Its five-cylinder engine is also far more characterful than Lancia’s four. It feels considerably better screwed together than the lightweight Italian. If you had to take one for a blat just for the fun of it? Integrale every time.

Another oddity about the Delta Integrale is that when it comes to modern classics, the original is usually the most valuable. Successive generations tend to dilute the original formula and are worth significantly less. The exception to this rule usually points to a homologation car – think BMW E30 M3 or Mercedes 190E 2.5-16 – and the Integrale is no different. The original 8v cars are the most affordable and they do have their adherents.

With ‘just’ 136kW to call upon, the original Integrale will scuttle to 100km/h in 6.4 seconds in pretty much any weather condition, and modern tyres extend its capabilities beyond anything we experienced in the late Eighties. Some prefer the way the lighter turbocharger spools up lower in the rev range, although compared with later models the 8v runs out of puff a bit above 5000rpm.

That first Integrale sent power from the front transversely mounted engine through a five-speed transmission to all four corners via an epicyclic centre differential. This delivered a nominal 56 per cent front, 44 per cent rear torque split, with a Ferguson viscous coupling varying the front to rear split as required. At the back was a Torsen rear differential, which could apply a further torque split left and right. Lancia balanced the effective gearing of the larger 15-inch wheels with a shorter final drive ratio compared to the HF 4WD.

The brakes were also uprated to 284mm ventilated front discs, augmented by a bigger master cylinder and servo. The front springs, struts and dampers were uprated and the body clothed with blistered wheel arches to accommodate the wider 195/55 rubber.

A louvred bonnet, wraparound bumpers, new driving lights, faired side skirts and body-coloured mirrors also featured. But better was to come.

Competition afforded Lancia a massive advantage in the development of the Integrale. Rather than relying on a planned product development schedule or feedback from customers, Lancia was bombarded with forensic feedback on the performance of the Integrale at every rally stage. More than that, it was also harmed with all of the intelligence it gleaned from rival competitors. This allowed for a rapid prototyping and test cycle, with the result that the Integrale 8v was in market for a mere 22 months.

Its replacement was the car you see here, brought to you by our friends at Young Timers Garage, the Integrale 16v. At the tail end of 1988, Toyota began campaigning the Celica ST165 as its rally weapon, with its 16-valve 3S-GTE engine co-developed with Yamaha. In the capable hands of Carlos Sainz, Juha Kankkunen and Kenneth Ericsson it started to score regular podiums, and won the RAC Rally. Lancia needed a 16-valve head on the Integrale to deliver more power at the top end. It also switched the hubs to feature a five-stud pattern, the bonnet was reprofiled to accommodate the taller cylinder head design, the wheels became wider again and the front/rear torque split was changed to a more taily 47:53.

Introduced at the 1989 Geneva Motor Show, the Delta Integrale 16v lifted peak power to 147kW

(a neat 200PS) and could sprint to 100km/h in 5.7 seconds. The engine came in for a number of tweaks aside from its better breathing, with bigger injectors, a next-gen intercooler, and an updated Garrett T3 turbo. The model had a mid-life update in 1990 with a revised interior featuring dark grey Alcantara with diagonal stripe contrast velour. Recaro seats were offered as an option, available in dark grey or green Alcantara or perforated black hide.

In many regards the 16v is the sweet spot when it comes to Integrale buying. It’s that little bit more modern and capable than the early cars and many of the niggling issues have been ironed out. The 16v is also considerably more affordable than the subsequent Evolution models.

These were properly special and came about because of an entirely unexpected turn of events. Lancia quit rallying. Although the Delta Integrale Evolution was shown at the 1991 Frankfurt Show, Lancia’s factory interest in rallying ended that year, the Integrale 16v having claimed both the driver’s championship, with Juha Kankkunen claiming his third championship, and the manufacturer’s crown, the latter for the fifth time on the bounce. Instead Fiat diverted its motorsport focus to Alfa Romeo and the development of the 155 touring car. What was there left to achieve with Lancia? Quite a lot, as it happens.

A contract was agreed with a number of privateer teams to campaign the new Evolution model in 1992. If Lancia was out of the game officially, then unofficially it was still diverting plenty of budget both to the development of the Delta Evolution and to Jolly Club, who took up the reins of Lancia’s WRC development program from the start of 1992, albeit with cheques still coming from Lancia and the workshop still being the existing Abarth facility. The 1992 season would see the marque claim its sixth consecutive manufacturers’ title. And it would be Lancia’s last, that baton then being passed to Toyota and, subsequently, the epic dust-up between Subaru and Mitsubishi.

The Delta Evolution road car was something very special. Power lifted to 154kW at 5750rpm, and the steering rack and an accessory oil cooler fitted. The control arms of the suspension were now massive box sections and the front strut towers were raised and braced. Bigger Brembo brakes, chunkier Speedline alloys shod in 205/50 rubber and a freer-breathing exhaust were standard with Bosch six-way anti-lock brakes, a metal sunroof and air conditioning available as options.

It also looked the business, with the even wider box arches now consisting of a single complex pressing rather than being welded on. The beadier projector headlights give it a meaner squint, there’s an even bigger bonnet bulge with additional venting and a three-position roof spoiler. It’s a serious piece of kit. From late 1992, assembly of the Evolution was contracted to Maggiora, who moved into Lancia’s old Chivasso plant. The Evolution was the last of the Deltas to taste success in rallying.

Its successor, the Evolution II was never homologated as a rally car. Its role was to be a beautiful send-off to the Delta Integrale. Now fully catalysed, the engine nevertheless lifted peak power to 158kW and torque to 314Nm, courtesy of a Marelli ECU and new Garrett turbocharger. It was also treated to 16-inch alloys, standard Recaro high-back seats, a leather Momo steering wheel, an aluminium fuel cap and a cylinder head finished in red. The Evo II was only ever offered in three colours, buyers getting a choice of white, red or dark blue, contrasting with a beige Alcantara interior.

True Delta aficionados will know that there was a one-off Evolution III model, handcrafted by Maggiora and finished in violet. It’s called the Viola as a result, wielded 174kW and featured a host of driveline updates. As vanity projects go, it’s a beauty.

In all, Lancia built 44,926 Delta Integrales. By any measure you choose, the Integrale was a massive success. Its legacy is unimpeachable. More than three decades have passed since Lancia walked away from world rallying and it’s still the most successful manufacturer in the sport’s history and the Delta remains the most successful rally car of all time. We may never see its like again. Hail to the chief.

Car supplied by Young Timers Garage

Along came a spider

We’ve covered the one-off Evo III, but the Delta Integrale Evo and Evo II were also offered in at least 11 limited edition models as Lancia really tried to milk the formula. The most unusual Integrale of the lot, however, was the Delta Spider Integrale, a two-door drop-top gifted to Fiat president Gianni Agnelli in 1992. This convertible featured a shorter wheelbase than the five-door hatch, and the body was braced and stiffened. Agnelli drove it until his death in 2003 whereupon it was put on permanent display at the Museo Nazionale Dell’Automobile in Turin.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesModern Classic: Dodge Viper RT/10, one of the wildest production cars of the last 40 years

The wildest and most outlandish production car of the last four decades? The original Viper has a strong case.

-

Features

FeaturesModern Classic: Porsche 968 Club Sport

How Porsche’s transaxle four signed out on a heroic high.

-

Features

FeaturesModern Classic: Tickford TS50, the legendary HSV rival that never quite got into top gear

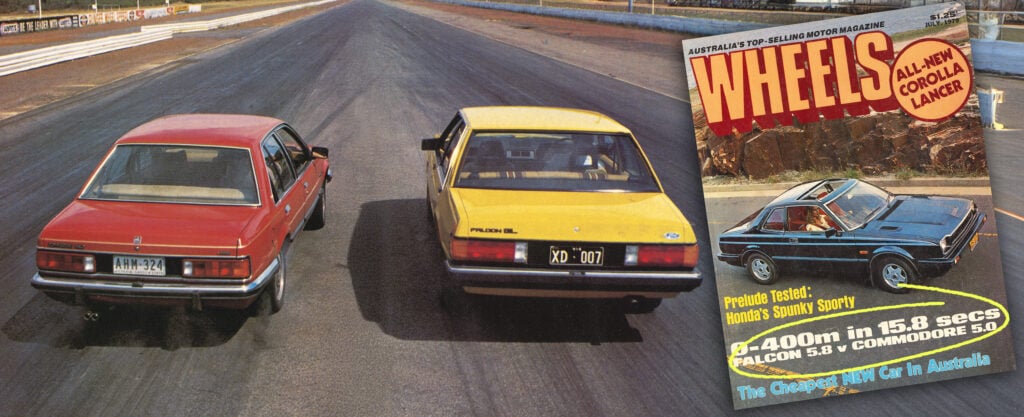

Tickford’s 5.6-litre big bangers couldn’t resurrect the AU Falcon’s reputation back in the day, but time has smiled on these hand-crafted specials.