Alan Jones has some typically direct advice for Oscar Piastri.

“He just needs to keep the dickheads away. Not let things get under his skin,” Jones says bluntly.

The 1980 world champion knows the kid is good and confidently predicts he will be a world champion at some stage during his Formula One career. That’s a big vote of confidence from one of the toughest racers to ever strap into a grand prix car.

So, here is some history and context. Jones is brutal and honest. He has no time for BS and, even at 80 years of age, delivers his opinions like a one-two punch in the ring. There were times when he really let his fists do the talking, once in a road-rage confrontation in London and another time when he dropped a belligerent car dealer after the South African Grand Prix. There was also a stoush with a circuit official who tried to stop ‘AJ’ on a race weekend in Australia…

Famously, he worked against his Williams team-mate Carlos Reutemann in the 1981 title decider as payback after the Argentine had ignored team orders earlier in the season and stolen a win from Jones. Nelson Piquet, driving for Brabham, claimed his first world title thanks to Jones and his mind games.

“Reutemann was f***ed in the head and gave up,” Jones recalls, speaking with Wheels at his home on the northern Gold Coast. “I lapped him in that race, which was ridiculous.

“I’m still hated in Argentina to this day. Back then I needed a police escort from the airport to the hotel, and taxi drivers – and even marshalls at the track– were flipping me the bird.”

Many said Jones was even tougher than Australia’s original gritty world champion, Jack Brabham. Sir Jack was known for dropping his car’s back wheels off the track to fire stones at his racing rivals, a trick he learned in dirt-track speedway at home in Sydney. Jones? He was tough. Uncompromising. Driven. Successful.

“I was a pretty aggressive driver. If someone passed me, I took it personally. If they touched me up, that was fine. I’d just tell them ‘I’ve got you in my book for next time’,” Jones said. “If somebody asked how I’d slept I’d tell them like a baby, even if I’d been awake all night worrying about something. Never show weakness, that was my mantra.”

Jones turned 80 shortly after this interview and lives a quiet life with his second wife, Amanda, and their three dogs and a cat. He’s had a tough time after suffering a heart attack this year that has slowed him down but not beaten him. He loves MotoGP racing, monitors the Supercars scene, and tracks Piastri in F1. “What gets me up in the morning is certainly not mowing the lawns,” he laughed.

Jones grew up in a motoring family. His father Stan was a car dealer in Melbourne and won both the Australian and New Zealand grands prix as a driver. But he was never supportive of his son’s ambitions and AJ – with his first wife Beverley – resorted to renting rooms at their home in London and selling second-hand cars to fund his racing.

He scored his big breakthrough in the Austrian Grand Prix in 1977 driving an unfancied Shadow, before being recruited to lead Williams Grand Prix. “I always thought I was good enough,” he remembers. “But Formula One has never been easy. At the end of the day, there have always been 20 million young men around the world who want to put their arse into 20 cars on the grid.

“A lot of it is luck. And the other thing is, when you get to that place, you’ve got to be able to take advantage of it. There are quite a few young buggers with enormous talent who will never be able to show it.”

Jones had already starred in brutally fast V8 Can-Am sports cars in the USA and he loved the challenge of getting the best from the original ground-effects F1 racers, which used inverted wings to suck themselves to the road. He muscled his way to the front, much like Nigel Mansell in a later generation. He took the same approach off the track.

“If you’re a real racer you just want to put your arse in a car and race. All the rest is justification. I hated doing the PR stuff. “If had to go to a dinner, and I was sat next to the MD’s wife, she might ask if I’d had any bad accidents. So I would say ‘There was that time when my left arm was ripped off, but it’s amazing what they can do with micro-surgery.’ I would just have some fun, to get through the meal.”

His view of modern F1, therefore, is no surprise. “I couldn’t stand being in F1 now. I would love the money and the private jets. But not the rest of it, like turning up to the interview pen after the race.

“I don’t want to be one of those ‘in my day’ people, but I’ve lost it with Formula One to a certain degree.

If you saw a gap you went for it. You rubbed wheels. Now there is a bloody inquest, or you get fined 3500 grid positions into the next five races.

“It’s called racing. Now you’ve got to be careful, you can’t do this and you can’t do that. A good old ‘brake test’ to someone behind never hurts.”

Jones bailed on F1 because he was homesick and frustrated, but he tried two comebacks. The first with the Arrows team was a total disaster, starting from a cockpit that was too small and had him resorting to a hammer to make space. Then came a big-money deal with the Beatrice food conglomerate in the USA, along with a Lola chassis and a Ford V8 engine.

“I’ve always given 110 per cent in my racing and the only thing I ask is 110 back. If the owner or team put in 110, then I would be happy. But the Ford Motor Company were so full of shit. Their engine wouldn’t pull the skin off the proverbial.”

Things were so bad Jones deliberately drove off the road and into an early retirement at the Portuguese Grand Prix in 1985.

“It took me three goes to get the stupid thing bogged. I thought I might hurt myself.”

He had dabbled at home with some touring car racing and, after his full-time return to Australia – there is no time to talk about the failed attempt at farming, or his boat dealership – was a regular through the 1990s in what has become Supercars.

“When I was back in Australia I thought I might as well go and race something. I loved racing the Porsche 935 for Alan Hamilton and won the Australian Championship (with 16 wins from 16 starts). You always enjoy it when you’re winning, but it was a beast of a thing to drive… we had a good team and Alan was a ripper bloke.”

He raced Commodores and Falcons, even a Mazda RX-7, but never threatened the scorers at Bathurst and couldn’t mount a successful touring car campaign.

“It’s amazing the things you forget. At Bathurst in ’94 I was dicing with Brockie in the wet. We were inches away from each other for 15 or 20 laps and it was great. He was clean and never did anything dirty.”

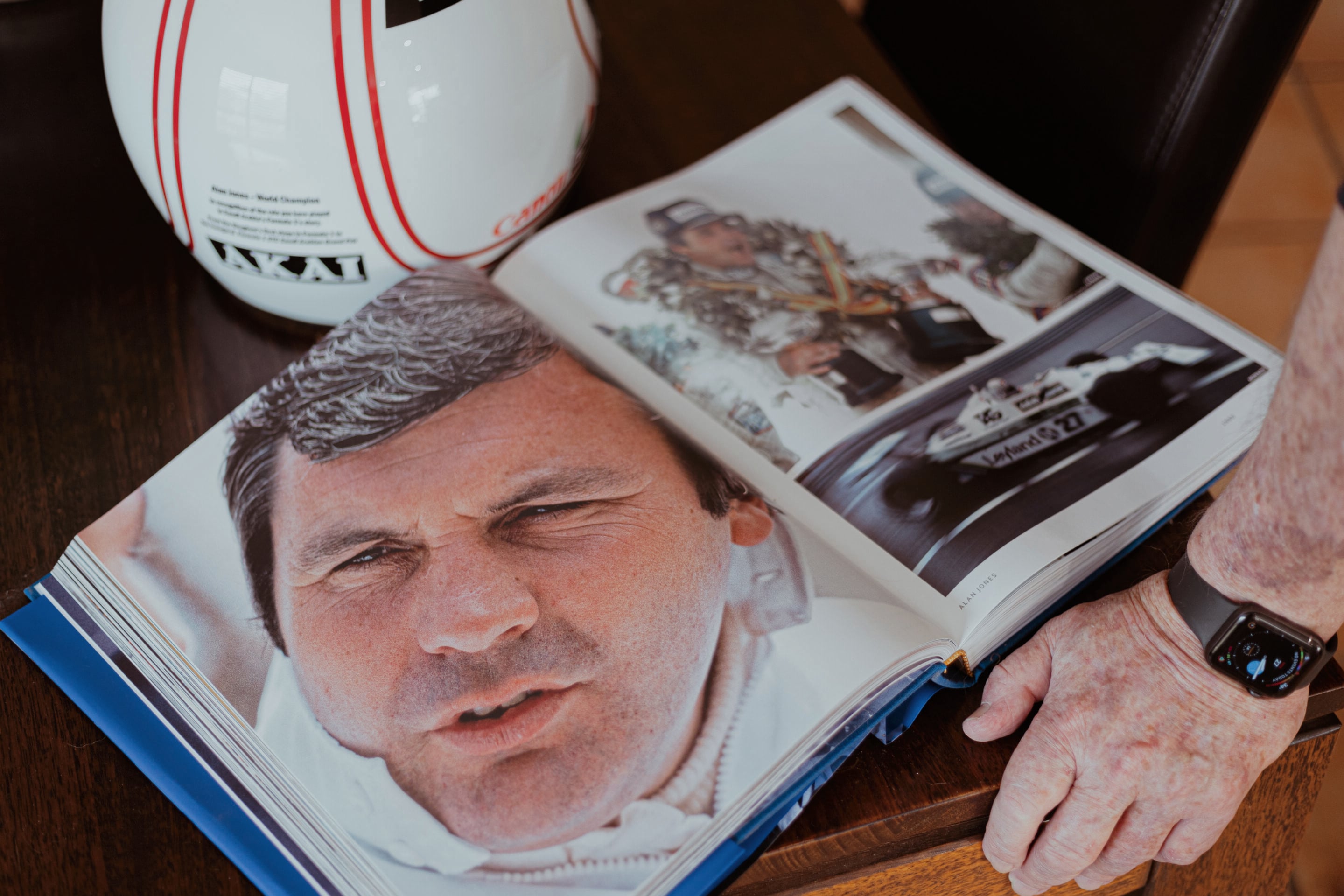

Life on the Gold Coast in 2025 is not great, but Jones is pragmatic and honest. There are no signs of trophies and just a couple of pieces of memorabilia. The real memories are in his head.

“What can you do with trophies? You can’t eat them. Nigel also sold all his trophies. I’ve been very fortunate. I’ve got a very active wife who is very clever with computers. Amanda has given me twins, who keep me on my toes, and Zara is into horses and Jack is mad on his golf. There is also Christian (his adopted son with Beverly). I have a daughter in New York who is a solicitor and another much older daughter in Tasmania, and a couple of grand-daughters. “They are all interesting,” he laughs.

Despite the absence of sentiment and silverware from his career, he is chasing down his F1 trophy – it’s a replica, after the original was sold – after loaning it to Motorsport Australia and nearly losing it.

Asked to reflect, Jones has straightforward views on other Aussies in F1.

“Jack Brabham was a pretty straightforward sort of a bloke. When I first got to England I asked if I could look through the factory, and he said ‘Don’t bring any of your mates’. I like [former Aussie early ’70s F1 driver] Tim Schenken, even if a lot of people don’t. He was a bloody good driver and outside F1, he drove works Ferrari sports after all.

“I don’t have a great deal to do with Mark Webber. He’s nice. I never really rated him at the beginning, but I took Christian to a go-kart race in Canberra a thousand years ago and this kid came up and asked how to get to F1. I probably gave him a smart arse answer, as I would have in those days, and it was him.”

What about Piastri, then, and the battle for the 2025 world championship?

“He’s obviously doing a good job. He keeps cool. He’s fast,” said Jones. “He’s pretty savvy with his handling of the press. When I was ahead in the standings people were already saying ‘Good luck champ’. I used to hate that.”

What then, is Jones’ view of the championship battle. At the time of this interview with Wheels there were still four races of the season still to run, and Jones was optimistic.

“I don’t know what is going to happen. To be honest, I think mentally he (Piastri) is the stronger of the two. I certainly felt that way four or five races ago. But Lando has bounced back. Two or three races ago I would have said Oscar is quicker. But now I think they are on a par. Mentally, if it gets down to the end then I would back Oscar. I think he is stronger.

“But what’s making it really interesting is Max Verstappen coming back. I think he’s stronger than the two of them put together.”

Even so, no matter where the title goes for 2025, Jones says it’s not even close to over for Oscar Piastri. “Really, it’s only his second year, and he is only 24. With the talent he’s got there will be people chasing him. They all wouldn’t mind having him in their team.

“I think he will have other chances. But he should go for it anyway. Then again, if I say ‘Go for it now’ then what has he been doing up to now?”

The article originally appeared in the December 2025 issue of Wheels. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesThe Wheels Interview: Peter Hughes, former Holden designer, on the brand's golden years

Designer Peter Hughes reminisces about his work and colleagues during his ‘fortunate’ career working for Holden in its most productive years.

-

Features

FeaturesThe Wheels Interview: How Bernie Quinn's Premcar solves problems for some of Australia's most popular makes

Bernie Quinn was an underperforming, self-confessed ‘battler’ before he found his feet as an engineer at Ford. These days he’s the CEO of Premcar, a company he has built up with a former colleague to create uniquely Australian answers to a variety of automotive questions.