Keels Weel is the radiator man.

His first was for an ancient ACCO truck and he now fronts a $1 billion Queensland company, PWR, that supplies cooling equipment for all 20 cars on the Formula One grid. PWR also has the answer for all sorts of other cooling questions, in top-level motorsport and beyond. Supercars at home and NASCAR in the USA? Tick.

Grey nomads hauling a caravan and off-roaders needing grunt? Tick. Rockets and missiles? Tick. Satellites? Tick.

“We’re just poking along. Doing what we do. It’s not too shabby,” Weel tells Wheels in a masterful demonstration of understatement.

Yet he is on first-name terms with people like Red Bull F1 supremo Christian Horner, engineers at some of the world’s top car companies, and can explain the most intricate details of the top-secret cooling systems being developed for a defence system to help protect Australia from potential missile attacks.

“It never ceases to amaze me, the things we make. It’s jewellery,” said Weel.

But jewellery was a long way from his mind when he took the first step on the road to PWR, creating a radiator for an old-fashioned International ACCO truck while he was running a wrecking yard at Warrnambool in Victoria. He never finished high school but talked his way into an apprenticeship as a mechanic after arriving in Australia with his parents from Holland in 1954.

“I sold a lot of radiators in the wrecking yard,” he recalls. “You have discussions – possibly arguments – and I told this guy ‘I reckon I can make that. I don’t know what all the fuss is about’. That was my first.”

He eventually supplied a string of 10 outlets for K&J Thermal Products in southern Queensland before selling the business and creating PWR – it stands for Paul Weel Radiators, after his son – just before the turn of the century.

Creating a single-core radiator looks like child’s play in 2025, when PWR supplies cooling components – looking nothing like a traditional box-shaped radiator – to every team in Formula One. There can be as many as 14 individual components for each grand prix car, including one intercooler for a turbocharger than can slash the inlet temperature from 250 degrees to just 20 above the ambient – in less than 20 centimetres. Each is individually shaped and crafted to sit inside the cramped confines of the car without compromising its basic function.

Then there are the new-age cooling racks which house dozens of individual batteries, with more innovations coming from PWR’s top-secret development section and the 30-metre radiator-specific wind tunnel it developed in a joint venture with Red Bull Racing.

PWR is about to move to a new site on the Gold Coast, doubling its footprint and capacity. There are also PWR branches at Indianapolis in the USA and Rugby in Britain. The total workforce is around 600 people, spearheaded by 55 qualified engineers.

“Our engineers are brilliant. And they get pushed by engineers from other places,” Weel says. “We’ve doubled our business in the past four years, and we’ll go close to doubling it again in the next four years. It’s a pretty big machine. But it’s not about me. It’s about the people around me and the team we’ve put together. Our whole business is made up of teams of people that want to be the best. And they strive to be the best.”

Arriving for a factory tour with 71-year-old Weel, he could not be more different from the sort of slick suit-and-tie types who dominate the world of automotive senior management. He is a crusty greybeard who would look right at home on an outback property, toiling in a big drafty shed to maintain and improve his farm equipment. Admittedly, he does have 200 acres complete with a herd of wagyu beef cattle on his property in the lush northern hinterland of NSW.

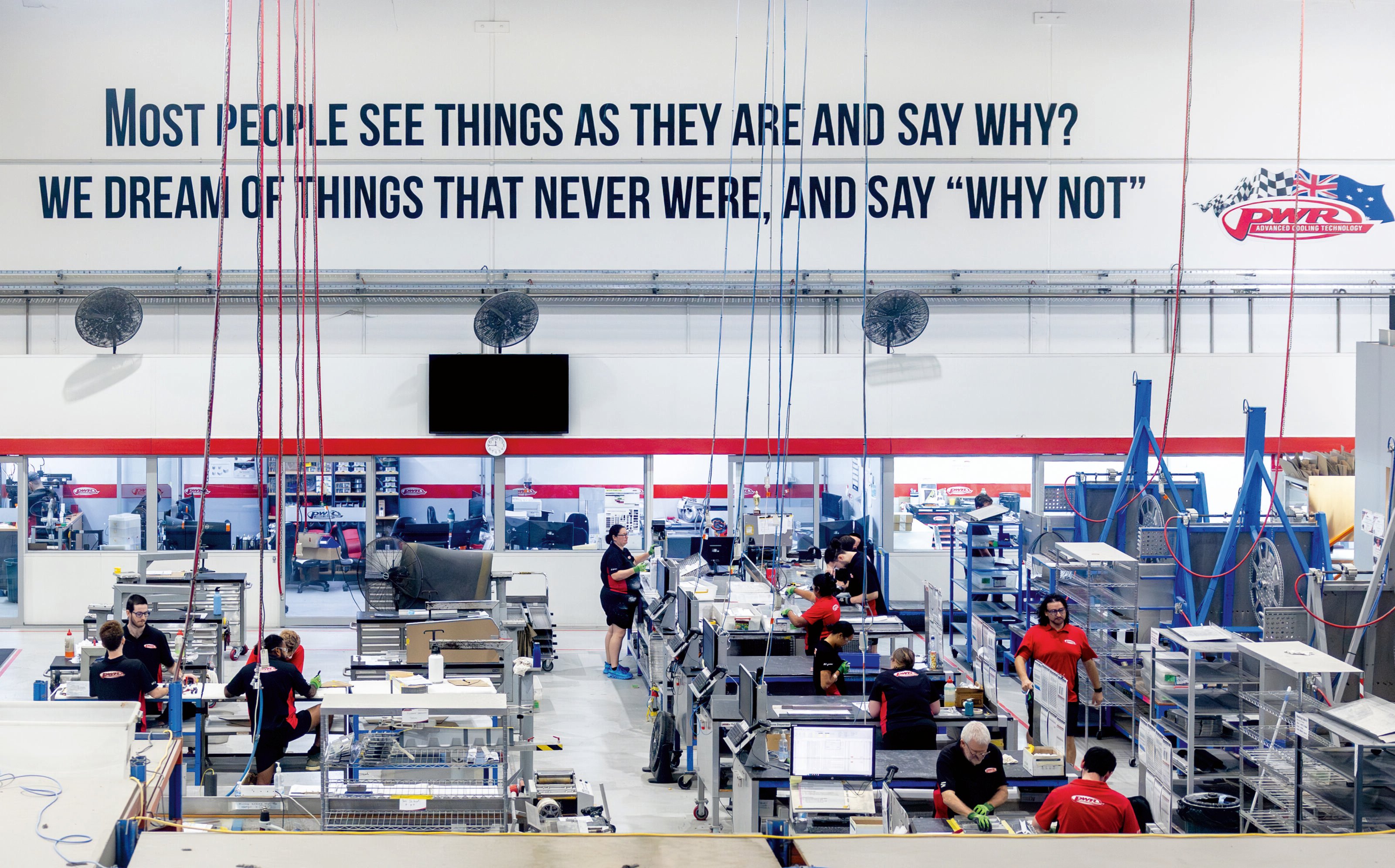

Nothing is outsourced by PWR – there are deliveries of raw materials, mostly aluminium in some form, at one end of the factory and deliveries of finished coolers for customers at the other. The showroom in reception is stocked with aftermarket niceties, all stamped with a big red PWR logo, that you might see in the nose of an over-boosted drift car or on a diesel HiLux tackling an off-road challenge, or a Formula One car on the grid at Albert Park.

Between the start and finish there are special machines and 3D printers, but the highlight of a visit is seeing the highly experienced fabricators and welders. They turn raw aluminium, in blank rolled sheets and piles of tubing, into crafted excellence. Seeing the specialised welders doing their work is, alone, worth the visit. There are hermetically-sealed rooms with giant 3D printers, fabricating pieces that look ready for NASA or SpaceX, and other stuff which is the future of cooling in forms which are still highly confidential.

Weel arrives from a rushed overseas phone call and is wearing the same uniform of shorts and polo shirt as his staff, with a PWR cap and steel-tipped safety boots. He knows everyone by name, stops often to chat, and points out the commercial kitchen that serves a free lunch to everyone each day.

“We still feed everybody, free of charge, as we have done since day one. It’s one of the little things that means a lot to people,” says Weel. “We still run it as a family business, with family values, but we have corporate goals.”

Those corporate goals track back to the very end of the 20th century, when Weel’s son Paul was getting started in a motorsport career that eventually took him to Bathurst in Supercars, a win in the Baja 500 off-road race in the USA, and will see him on the starting line for the Dakar desert duel in 2026 – most likely in a Ford Raptor. He had already joined his father in business and, not unsurprisingly, had been tasked with learning a trade for the time when he was finished with motorsport.

“Paul was doing a fitting-and-machining apprenticeship and I suggested he go to TAFE and learn to weld aluminium,” Weel recalls. “I told him I reckoned we could sell some competition radiators. I told him to register a company and start paying tax.”

“We still run it as a family business, with family values, but we have corporate goals.”

Soon after came the first aluminium forge and the start of bespoke manufacturing. There was still motorsport, most notably when Kees took on Team Brock – “that wasn’t fun, just a nonsense and a Holden deal” – but victory at Bathurst in 1998 with Stone Brothers Racing, and then a contract with the Holden Racing Team, proved the quality of PWR products.

“When we finished supercars in 2008 I said to Paul, ‘We really have to put some effort into PWR’. That was the main reason he stopped racing.”

The effort was reflected when the company was eventually floated on the stock exchange in 2015, with 100 million shares at $1.50 each.

“They went straight to $2.85. Today they are about $7.70 and they went as high as $11.50. The true value is probably $10 or $11,” says Weel.

It would be rude to ask his net worth, but life is comfortable and the father-and-son pairing often travel to the USA as Paul drives in top-level off-road racing with Toby Price as his team-mate. One of Kees’ grand-daughters, Abby, is also a world-class dressage rider. But the PWR story is not really about money, or the success of family members, it’s about technology. And survival.

“We built a new building in 2004-2006, it took us two years, and then the Global Financial Crisis came. We had this flash building and no business,” Kees recalls. “In 2008 I went to the USA and Leigh Diffey (one of the world’s top motorsport commentators and a super-booster for PWR) got us a meeting with Jack Roush (one of the most influential people in American motorsport) and within two years we were in NASCAR racing and the whole field was buying from us.”

Next came Formula One, through a chance meeting with Renault’s technical director at the time, Pat Symonds.

“We met at a trade show in Europe and he asked if we could build a radiator core. We built a radiator in six weeks, a bit crude, but it did not have one single square side and it was the size of a milk bottle.”

PWR was away.

“Within two weeks of Renault receiving it we got a call from Red Bull Racing, and the guy was insistent. We only had 35 people then. I won’t say he was crawling up our bum, but he wanted our help. Long story short, we did a deal. We supplied RB in 2010 with a full set of coolers for Sebastian Vettel and he (went on to) win four championships.”

“We always said it was our product, they said it was their driver, and so the story goes on,” Weel chuckles. We started supplying other teams in that period. We did a deal with RB to design a wind tunnel in 2011, and they designed it and we manufactured and installed it in 2012. Even today, that’s probably still the best tool in our toolbox. It sets us apart from any other manufacturer in the world trying to do motorsport, because we can replicate race conditions.”

It was a $1.3 million project but PWR “had no money” and it took investment from Red Bull and the Queensland government to get the job done.

The investment paid off with road cars jobs for Porsche and Aston Martin, the first of many.

“We made five coolers for the Porsche 918 Spyder. Aston Martin had a road car with problems. We designed the fix in an afternoon.”

There is more, much more, as Weel walks and talks about the newest direction for PWR.

“We started doing stuff for aerospace and defence in 2020. It was the week before Covid when we started doing that, so we had a spell for two years . . . But we’ve kicked on pretty good.”

There is stuff in the Gold Coast factory he cannot show me and PWR has just built a stand-alone site in the USA for its defence and aerospace work, with plans for a similar facility at Rugby in the UK. And then there is the move, later this year, into the new headquarters on the Gold Coast. It’s more than twice as big as the current site.

“There is a lot happening. I get shit done,” says Weel, frankly. “We are doing a program for the Australian government called the Moon-to-Mars project. We have a grant for $880,000. It’s for a particular cooler to go on that, that no-one else can manufacture.”

The stories keep coming and Weel talks about an annual turnover that’s currently sitting at $150 million. His products are good, but not cheap.

“Not everybody can afford our quality. And I’m not being a smartarse by saying that,” he begins, looking into the future.

“Probably the big growth area we see is in aerospace, although F1 is our technical driver. People love it. They push technology and spend a lot of money looking for the winning edge. They can waste a lot of money, but when they find something that works . . . “

Even so, the real key at PWR is commitment, something reflected in the relentless work ethic of Kees and his search for the next challenge.

“I think there is a certain amount of drive. And we’ve been fortunate to get into that business when there was no-one else,” he says. “We own all our Intellectual Property. That allows us to use that IP in different categories we’re not in. We’ve made radiators overnight. We’ve made F1 radiators within a few days. We’re absolutely flat-out.”

This feature originally appeared in the May 2025 issue of Wheels. Subscribe here.