The blokes at Fishermans Bend, Victoria, and Kidlington, England, have built easily the most effective weapon for road and track use since the legendary Phase III GTHO Ford Falcon of 1971.

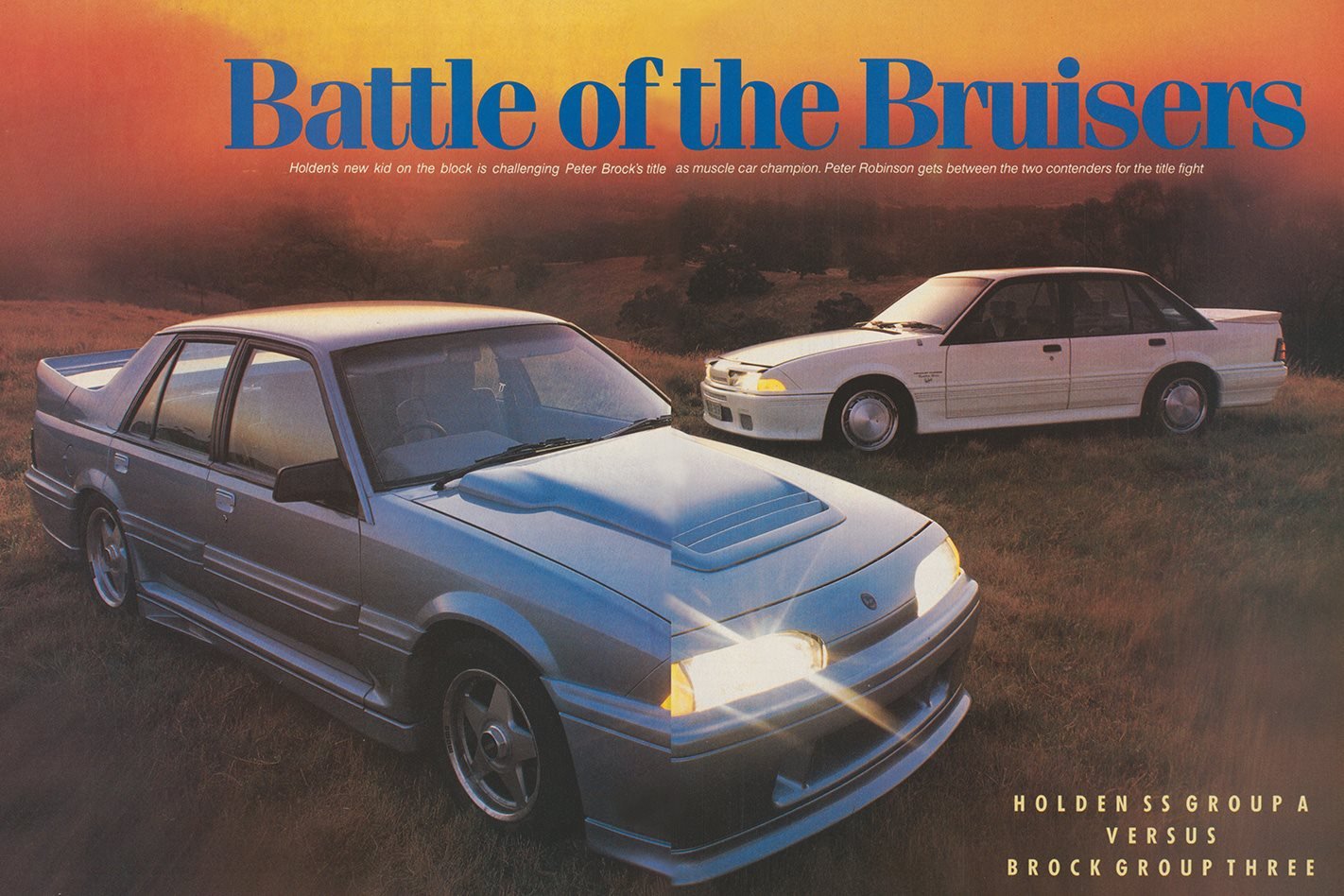

Battle of the Bruisers was first published in Wheels in March 1988

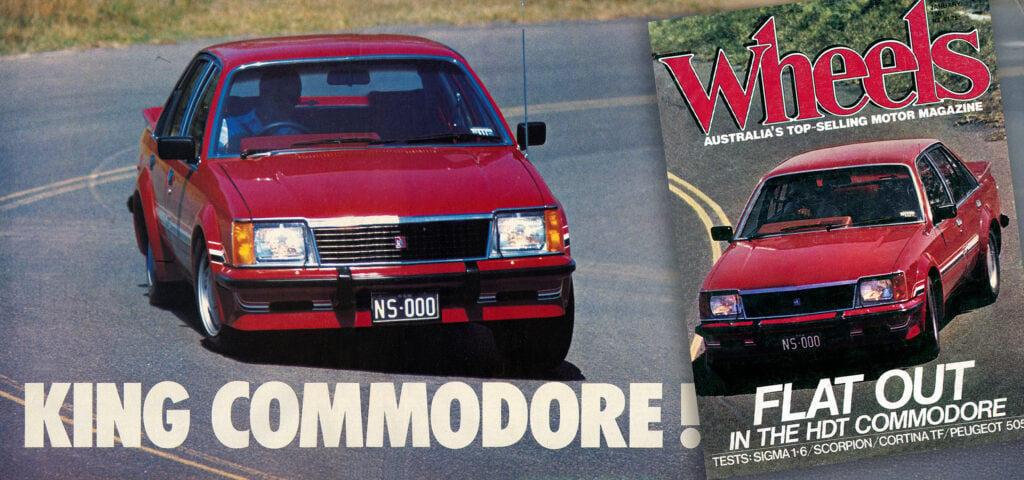

That’s not PR hype but cold fact. Holden’s new Commodore SS Group A spells the end of Brock’s HDT operation, at least when it comes to building modified Holdens. Good as the Brockmobiles have been, there’s no way the HDT can match the engineering skill, wind tunnel expertise, sheer dollars and marketing muscle that is going to build and shift 750 Group As in ’88.

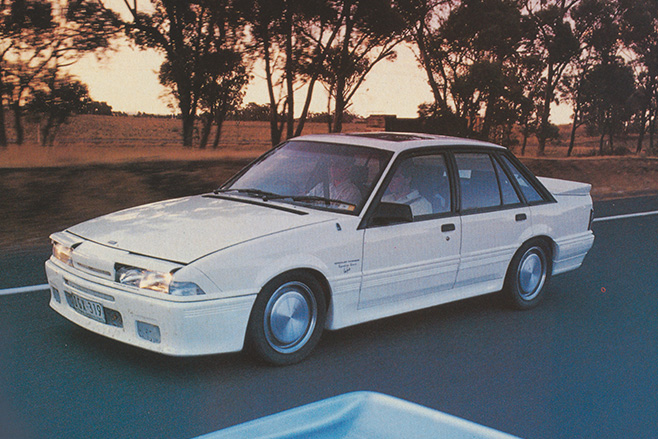

Lined up against the Group A is Brock’s Group Three Signature series of HDT Commodores (the Holden name doesn’t appear on the car). There’s still the old carburettor V8 engine, and the now discredited body kit, yet the magic touch of Peter Brock remains evident in the Group Three’s dynamics.

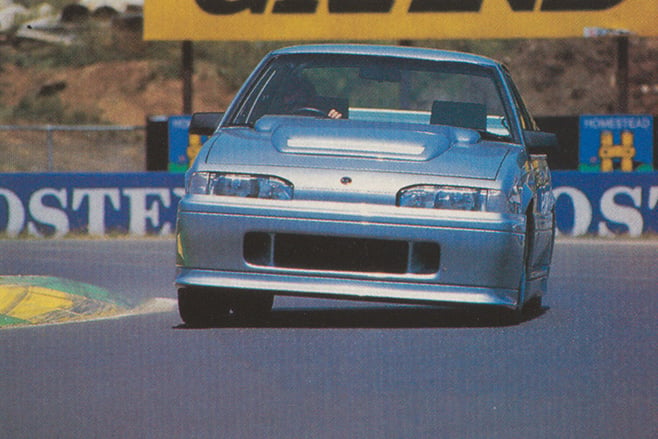

For starters, there’s the totally over-the-top body kit on the Group A. If it didn’t work so brilliantly in the wind tunnel it would be laughed off the street as an exercise in fibreglass foolishness.

From the deep tail section that sits atop the boot lid like a giant bird bath to the formidable front air dam, everything is targeted at lowering the drag factor and improving downforce for the track. From close up it looks mean and aggressive, clumsy and even bizarre, distinctive enough to hide its origin from many who see it for the first time.

In contrast, Brock’s Group Three looks mild, though not so long ago it was regarded as the essence of potency. There’s no hiding its Commodore beginnings, and its drag co-efficient is around 0.43 compared with the 0.32 of the Group A. The Group A’s aerodynamic advantage is considerable and benefits performance, roadholding and fuel consumption.

When we asked the HDT for a Group Three for this comparison we never expected to be given an automatic, but since 80 per cent of the Signature Series cars sold last year came with the three-speed auto it seems fitting enough.

Crank the engine over and it fires almost instantly. The idle is a smooth and quiet 500 rpm, and gives not even a whisper of what is to come. The clutch that felt strong and springy when the car was stationary is firm and beautifully positive on the move, and is stronger than the soft clutches fitted in previous manual V8 Commodores we’ve driven. The specs tell us the clutch has been improved to accept 15 per cent more torque, and that feels about right. Clutch and gearbox work superbly together. The short, precise gear change is perfectly matched to the robust character of the clutch. Swapping cogs is a pleasure.

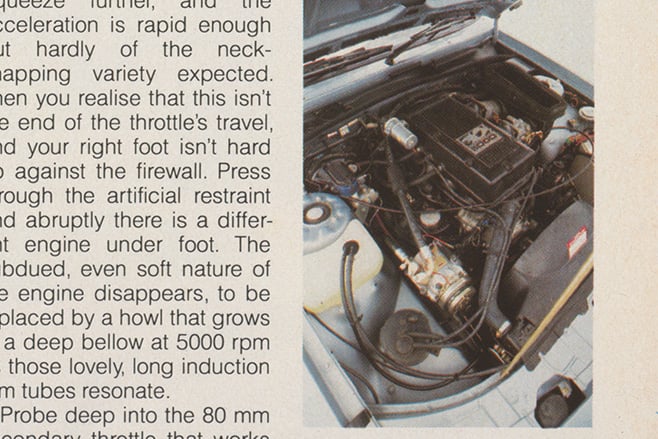

Prod the accelerator timidly and the V8 responds promptly. Squeeze further, and the acceleration is rapid enough but hardly of the neck-snapping variety expected. Then you realise that this isn’t the end of the throttle’s travel, and your right foot isn’t hard up against the firewall. Press through the artificial restraint and abruptly there is a different engine under foot. The subdued, even soft nature of the engine disappears, to be replaced by a howl that grows to a deep bellow at 5000 rpm as those lovely, long induction ram tubes resonate.

At 1000 rpm in fifth gear it will happily accept full throttle and pull away briskly, the exhaust note growing deeper from 2000 rpm. For all this impressive, tractable nature it is an engine that wants to rev to the cut-out.

Relaxed cruising calls for no more than an upward gear change – at 160 km/h the engine is turning over at just 3150 rpm in fifth gear – while a downward change turns it into a machine of rare capability.

The gear ratios match the engine perfectly, second is good for 106 km/h, third a marvellous 155 km/h that simply blows everything else into the weeds, while fourth will run to the cut-out at 207 km/h. Top speed, well, we don’t know. At the time of writing nobody had run the production car out to a true maximum speed. We do know it will go to 230 km/h or 4500 rpm in fifth. Holden estimates it will pull in 233 km/h – 146 mph in the old language.

And there’s more power to be had. Holden’s brilliant engine man, Warwick Bryce, says 250 kW at 6400 rpm and 430 Nm at 4000 rpm is entirely possible. How good is the VN Group A going to be?

An automatic HDT Commodore can’t hope to generate the same acceleration times. Look beyond the standing 400m time, however, and you will find Brock’s car is also a magnificent performer. Any automatic that takes just 15.8 seconds over the quarter is rapid indeed, and once the Group Three has overcome its relatively leisurely initial acceleration it virtually matches the Group A all the way to 120 km/h. There’s 1.2 seconds difference to 50 km/h, but this has grown by only 0.1 second to 120 km/h. Above this speed the superior aerodynamics of the Group A begin to have an effect and the Brock car can’t keep up.

Comparative figures reveal the Brock Group Three matches the Group A across the 400 m, while the old carburettor Group A was more than half a second slower. The HDT car lacks the wail of the Group A, struggles through valve train noises above 5000 rpm, and doesn’t have the crisp, free-revving ability of the injected engine. And it can’t hope to match the official car’s top speed.

Comparing the fuel consumption of an automatic with a manual car always works to the disadvantage of the auto. Never more so in this case. Over a hard 220 km on the road the Group A returned 6.0 km/L (16.9 mpg) while the automatic HOT car gave a disappointing 4.0 km/L (11.2 mpg). The Holden comes with the long-range 84-litre petrol tank where the Group Three must make do with the standard 63-litre tank.

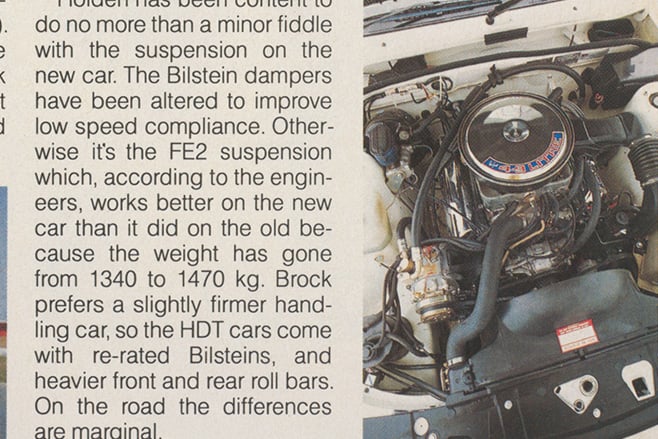

On the road the differences are marginal. Brock still insists his cars run 22 psi for road use. This made valid comparisons difficult, for the Holden men recommend at least 30 psi. The day we did this head-to-head shoot-out we had representatives of both companies present, making it impossible to run equal pressures.

Across the blacktop these cars are impressive by any standards, their sheer power and roadholding combining to flatten the steepest hills and straighten the tightest corners. The softer tyres of the Brock cancel out any advantage it might gain with its firmer suspension, so the relative lack of roll stiffness of the Group A must be balanced against the sidewall movement of the Brock car. Both still suffer from the performance Commodore’s long history of rear axle problems which induces bump steer from the rear over undulations and bumps. Only an independent rear suspension will provide an effective solution to this dilemma. At very high speeds the Group A’s outstanding aerodynamics improve stability, for above 160 km/h you can feel the body being pushed down into the road, where the Group Three becomes a touch floaty. The advantages in racing must be considerable.

There’s no doubt we have a new quintessential Australian muscle car. Holden’s Group A deserves to be ranked with the finest. Its engine’s versatility and the body’s aerodynamics have created an instant classic. There’s no argument. At around $46,000 you must buy the Holden. A Brockised Group A? Maybe the General can still learn a thing or two from its once favourite son, though you get the impression Holden made up its mind the Group A was intended to show the world, and not least Peter Brock, that when the General got serious no racing driver-turned-car builder could ever hope to meet the challenge.