“I just wanted to write a thesis, how the hell did I end up here?!”

Maurizio Ferrari had started the year as a fresh-faced university undergraduate, and now he was in the middle of tense negotiations, with all eyes in the room focused on a single black briefcase which sat in waiting atop a table.

Click! The gold clasps of the briefcase flick open in sync, the black leather lid lifting to reveal the contents – thick wads of cash. All of a sudden, despite being a typically hot and dry September day in Monza, it wasn’t the rising mercury that was causing Maurizio to sweat.

Having to abscond to a motor home in the heart of the Formula 1 paddock to escape the oppressive heat descending upon the Temple of Speed, the 28-year-old was now entirely out of his depth. Trained as an electrical engineer, he was instead acting as a de facto middle man and translator in a secretive back-room deal.

To one side of him sat his boss Ernesto Vita, an impossibly charismatic salesman with an enigmatic past. To the other, representatives from the newly formed Leyton House F1 team. And there, now sitting open directly in front of Maurizio was the briefcase, filled with more money than he had seen in his life.

Time to start counting.

This was but one chapter of a relentlessly absurd saga that is equal parts tragedy and comedy. A tale that begun in 1988 when a purple Rolls-Royce arrived at a nondescript Italian villa. Welcome, to the unbelievable but true tale of Life F1 – Formula 1’s worst, and most misunderstood, team.

Franco Rocchi had enjoyed an illustrious career building racing engines during Ferrari’s golden years, but by 1988 he was happily retired and spending his days painting. Entering the later stages of his life, Rocchi had fallen in love with his watercolours and not even a personal petition from Enzo Ferrari could lure him away.

Which makes it all the more impressive that when Ernesto Vita stepped out of a royal-hued Silver Spirit unannounced, he would be successful in convincing Rocchi to rejoin the world of building and designing engines for Formula 1. You see, Vita had a plan, and it was going to make him – and anyone who joined his endeavour – rich. Key to everything was Rocchi, and an engine design the ex-Ferrari man had worked on over two decades ago.

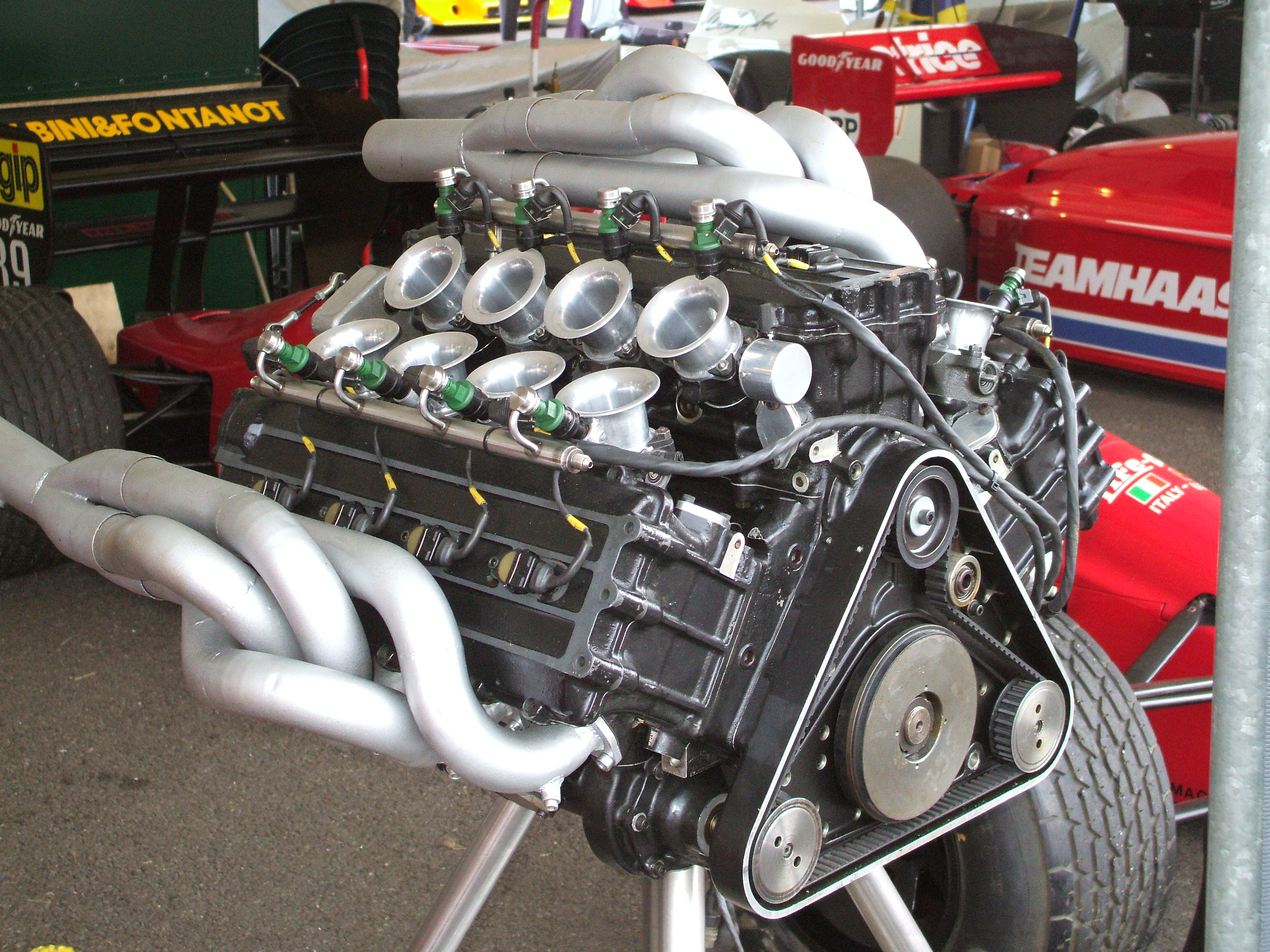

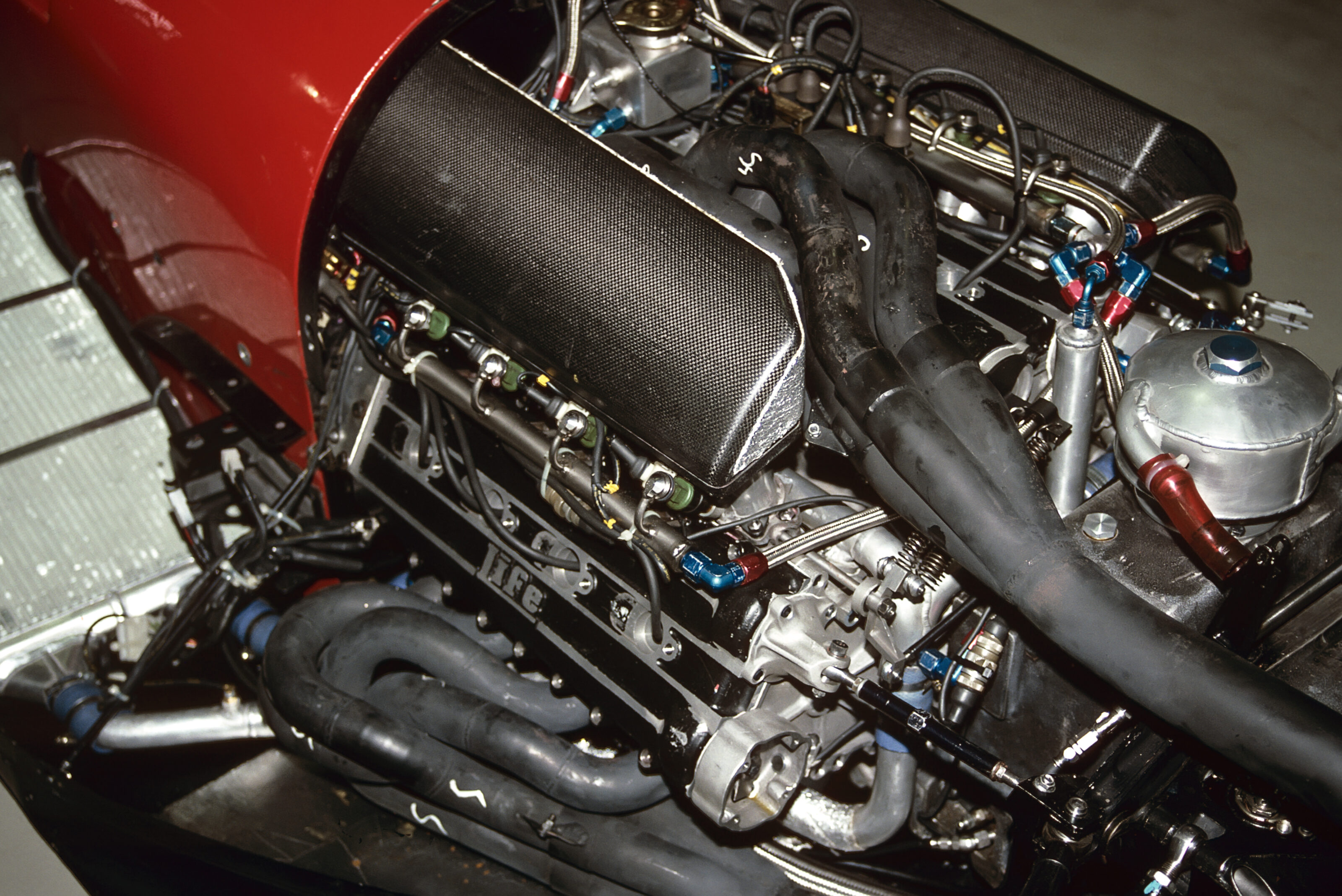

Back in the late ’60s Rocchi had toyed with designing a W18 engine for Ferrari, going as far as building a 500cc W3 as a proof of concept, with positive results. Ultimately though, Ferrari opted to go with the flat-12 design instead, and the unique plan was put on ice. That was until Vita walked through the door, commissioning Rocchi to design him a W12 to race in F1.

Some context: by the mid-1980s Formula 1 was on a runaway train when it came to turbocharging. While teams were turning the boost up on the new technology, the FIA was fighting a losing battle trying to keep speeds in check. The surprisingly un-French solution was a total ban on snails, with F1 moving to a 3.5-litre naturally aspirated formula. Down came the edict that teams could use as many cylinders as they saw fit (up to 12); let them breathe freely and go wild.

It was in the tech vacuum between turbocharging and natural aspiration that Vita saw opportunity and, importantly, profits. He recognised there would be multiple teams up and down the Formula 1 grid looking to replace their now outlawed turbocharged engines, and he planned to sell them Rocchi’s W12.

Being incredibly self-absorbed, Vita dubbed the venture Life Racing Engines (or Life F1 for short) after the English translation of his name. Having convinced Rocchi to join him, all that was needed were firm orders.

While Vita was a compelling salesman by all accounts, his silver tongue wasn’t enough to convince a single team to use the engine for 1989. Looking at it now, it’s unsurprising that the traditionally conservative Formula 1 cabal decided against throwing large wads of cash at a businessman with no racing experience and an unproven engine design.

This left Vita in a hole of debt. Wedged into a corner, there were two options. He could eat his losses and walk away, or go all-in on the biggest gamble of his life. He chose option two.

If those in pit lane weren’t going to buy into his sales pitch, Vita backed himself to start his own F1 team using the W12, and when inevitable on-track glory materialised, teams would realise the errors of their ways and line up in droves, cap in hand, begging for the chance to use his design. Easy.

Spoiler alert: it was not easy.

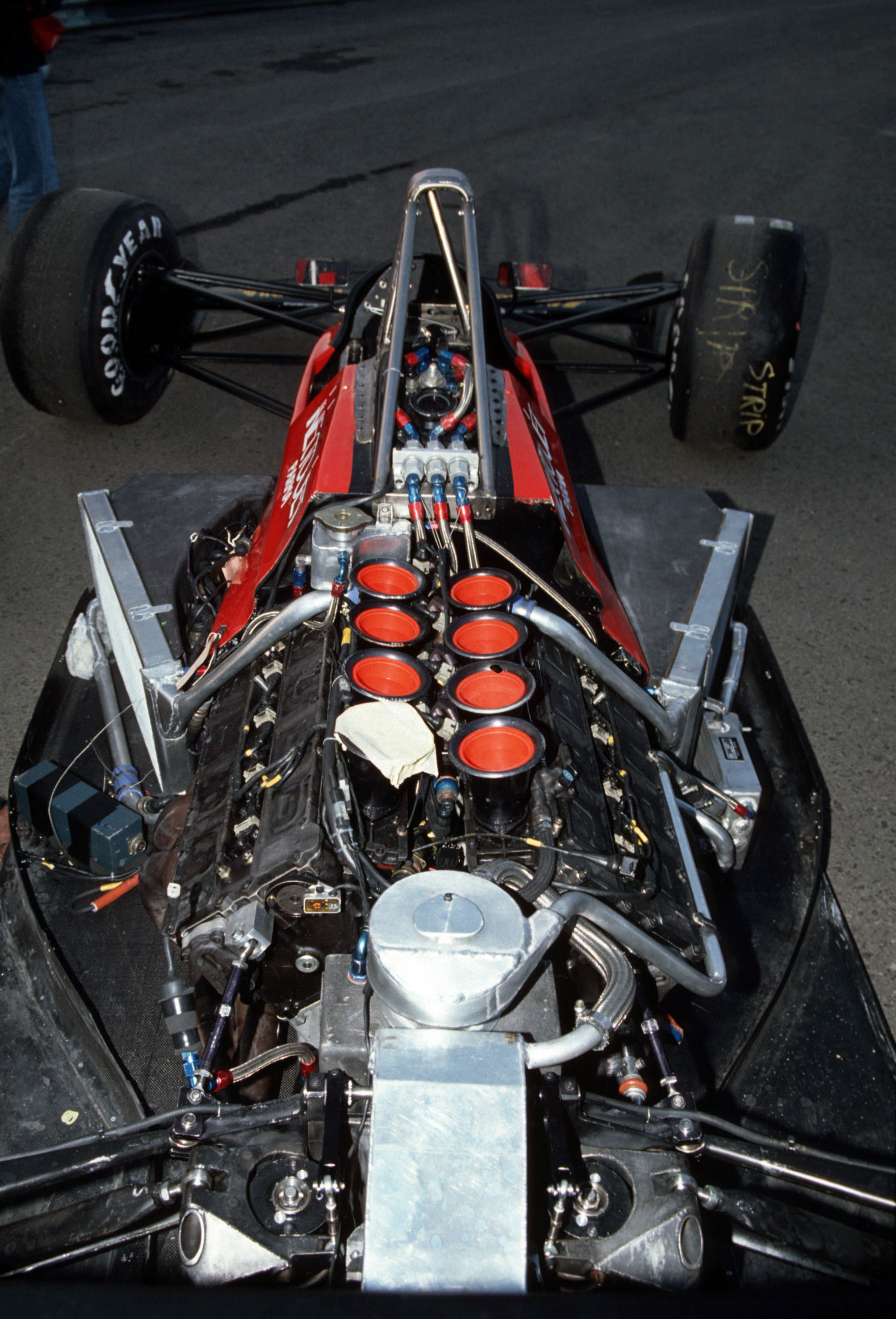

To get his team started, Vita purchased a warehouse in Formiginie, only a few kilometres from Ferrari’s home base in Maranello. His engine also needed a body to call home, so Vita purchased the F189 chassis built by an Italian Formula 3000 team, FIRST Racing, that had intended to compete in F1 in 1989 but never got off the ground.

Gianni Marelli (a former Ferrari engineer) was enlisted and tasked with making the chassis crashworthy as it had failed mandatory pre-season crash testing 12 months prior, and also with modifying it to accept the W12 instead of the smaller V8 it was initially designed for.

The first race was to be held in Phoenix in early March. By February, Life was yet to conduct a full test of the now renamed L190 and their driver Franco Scapini had just been denied the required super licence to take part in F1 events. Unsurprising, given in his 19-race F3000 career (then the feeder series for F1) he finished only four races, with a best result of 10th, and he failed to qualify 12 times. Australian Gary Brabham was brought in at the last minute as a replacement.

Formula 1 had reintroduced pre-qualifying for 1990, with the bottom two teams from the ’89 championship, and new teams like Life, having to compete in a one hour session from 8:00-9:00am on Friday each grand prix weekend. The four quickest cars then earned the right to take part in a 30-car qualifying session on Saturday, with only the fastest 26 cars in qualifying being allowed to start the race come Sunday.

However, with no 107 per cent rule, this meant that theoretically a team could find themselves starting a grand prix, despite being horrifically off the pace. Many did just that, but not Life.

In Phoenix, Aguri Suzuki set the benchmark time to escape pre-qualifying in his Larrousse – a 1:33.331. For context, Gerhard Berger set the eventual pole time at 1:28.664. Brabham’s best in the Life? 2:07.147. The Italian privateers were nearly 35 seconds off the pace.

A TCR car is closer to Max Verstappen’s 2021 pole time around the Red Bull Ring than Brabham could get to the slowest car allowed to even attempt to qualify in 1990. Life weren’t so much in a different ballpark, they may as well have been playing a different sport.

The reason for the colossal gap in speed was that in race specification Rocchi’s W12 had around 375hp/280kW at its absolute best. Honda’s RA109E V10 engine was capable of 710hp/530kW. The W12’s outputs were still several hundred horsepower down on even its nearest competitors – and we use that term very lightly. Hell, the Lotus 49 was more powerful back in 1967.

At the next round in Brazil, Brabham couldn’t even complete an out lap before the engine suffered a catastrophic failure and the car ground to a halt. It would be the last time the Australian would drive for the team. At the same time, the chassis’ co-designer Gianni Marelli departed after a disagreement with Vita, leaving Rocchi as the sole member of Life’s technical department.

Rumours that the team failed to fill the car with oil, prompting the failure in Brazil, are false. However, even with the right amount of lubrication, mechanics discovered several decades later that a critical flaw in the engine design meant the W12 was cursed to a life of destruction and rebirth in an endless, cruel cycle.

Bruno Giacomelli was enlisted to replace Brabham after Vita’s requests to other young drivers were either laughed at or outright ignored. Life was beginning to earn a reputation no one wanted to partner with. Having last raced in Formula 1 in 1983, pundits were confounded at the time as to why Giacomelli – who had an impressive track record up until that point – would return to the sport with such a comically under-performing team. So, we asked him exactly why he did sign up.

“I never thought that I could do something special,” Giacomelli tells MOTOR. “But I was quite interested in the fact that Mr. Rocchi designed the engine, and I just wanted to help the team to get better. To get better, to perform better. I never thought that I could do something special. Of course, I’m not that stupid.”

During his first lap in the car at Imola a drive belt for the water and oil pump snapped, the W12 expelled all of its coolant onto the main straight, and the team’s weekend was over by 8:08am on Friday. Bruno never got as far as engaging fourth gear.

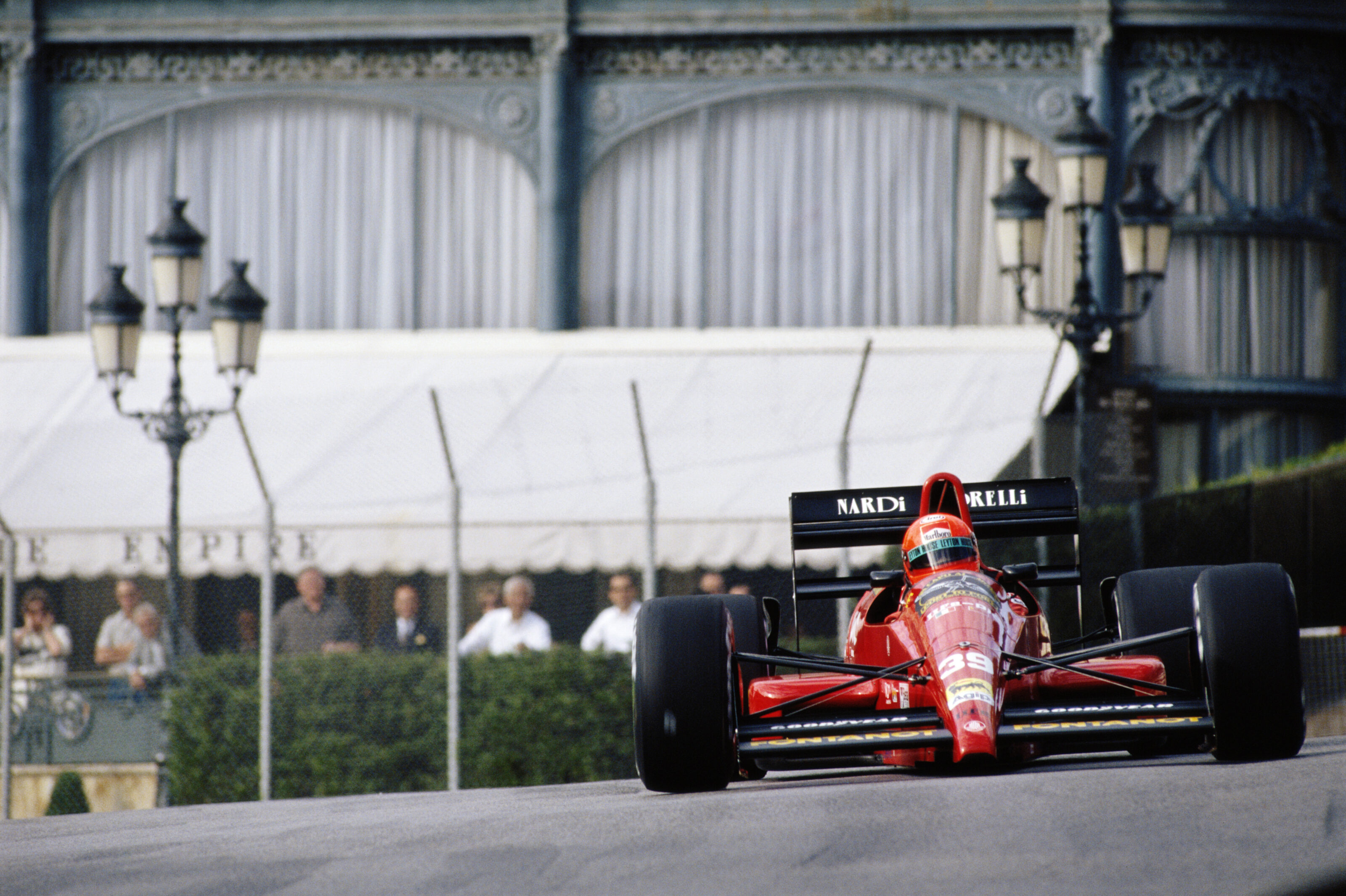

For the rest of the season, the pattern of ineptitude continued. Monaco, 14 seconds off pre-qualification pace. Canada, 21 seconds. Mexico, 2 minutes and 42 seconds. Silverstone, 15 seconds. Hockenheim, 25 seconds. Hungaroring, 25 seconds. Spa-Francorchamps, 21 seconds. Monza, 28 seconds.

This was the last time Life used the W12 engine, and it went out in typical style managing to complete just two laps. “And only one of them is timed!” laughed Giacomelli. “Then we broke the engine, and this time it was a good bang!”

Having been a mechanical draughtsman by trade, Giacomelli’s affinity for the technical side of the sport meant pairing with Rocchi was an opportunity he couldn’t turn down. Oh, and Vita promised him $30,000 a race.

Being aware the team’s chances of progressing beyond pre-qualifying were approximately zero, Giacomelli was more than happy to sign on for what seemed like an easy pay-day. Vita promised full payment at season’s end. You know where this is going. Media reports at the time recall Giacomelli having an upbeat demeanour during the 1990 season, despite the cataclysmically bad performances.

Today, however, Giacomelli tells MOTOR that he “doesn’t like talking about that time.” This probably has something to do with the fact he never saw a single cent out of Vita. “Maybe I should have taken an engine or perhaps the entire car with me when the team went bankrupt,” he said when Life’s inevitable demise was announced.

With the end of the season fast approaching, the team realised something needed to change, and a plan was made for the W12 to be replaced with a Judd V8 for the 13th round at Estoril in Portugal. The change was meant to occur much earlier in the season, but by round nine at Silverstone team manager Sergio Barbasio said the switch had been called off – claiming the cramped schedule between races prevented Life’s mechanics from making the necessary changes to the chassis.

The truth was that when Vita started the team, he had the equivalent of EUR50,000 in the bank, which disappeared quicker than the W12 could self immolate. It was a pitiful amount to run a F3000 team, let alone F1. That same year McLaren operated on a budget equivalent to EUR25 million.

The lack of funds was becoming a common theme for Life. It was the tar that stuck to the mechanics’ legs, preventing them from escaping the black hole of indignation in which they were consumed. As always, Vita had a plan that was going to solve all their problems.

In 1990 the Soviet Union was in the final stages of collapse. While the empire was falling and political unrest swept across the Soviet states there was still plenty of cash to be found in the Great White East. One thriving business was the Petersburg Industrial Company, or PiC, which had close ties to the military. Its chairman was amateur rally driver, Michail Pichkovsky, who was cajoled by Vita into funding Life Racing Engines to the tune of $20 million.

Not only would the partnership fix the team’s money woes, but it would bring technological assistance from the might of the Soviet defence industry. In celebration of the new partnership, the team was renamed Life-Pic, and the flag of the Soviet Union was placed on the nose of the L190 alongside the Italian tricolore.

But as with most things organised by Vita, reality turned out to be a little different to the original plan.

“It turned out that no money ever arrived, and although they thought that they could help us with their technologies, even their promised technology was not as advanced as the Formula 1 technology of that era,” Life’s chief mechanic Oliver Piazzi tells MOTOR.

The promised millions never transpired, but Vita still managed to get enough money out of PiC to buy a single Judd V8, which he paid for with the briefcase full of cash in Monza being counted by Maurizio. By virtue of having the best English in the team, the 28-year-old graduate was inadvertently promoted to team translator. “At the end of the season, I was pretty much taking care of all the relations with other teams and things like that,” Maurizio tells MOTOR from Italy, with a chuckle.

Leyton House assured Vita and his team that the Judd V8 would be worth every penny, being as good as new having done 0km since a complete rebuild. But when the Life squad returned to Formiginie they discovered that the crankshaft was seized solid. Turns out the engine had been over revved to more than 14,000rpm during testing at Zandvoort.

At this point, after relentless failures all season long, you would have forgiven the Life mechanics for throwing their spanners into the ocean and going home, wanting never to return to the wretched cut-throat world of Formula 1. But no, Life found a way.

Vita threatened Leyton House with legal action and a concerted press campaign if they didn’t rectify the transgression, which was enough to convince the fellow backmarkers to swap the dud Judd for a fresh unit. Leyton House mechanics arrived late on the Thursday before the grand prix to retrieve the broken engine, leaving the Life mechanics to work through the inky dark of night to reassemble a car that had become the butt of a year’s worth of jokes.

“I think we were more resilient than they thought, as we were able to do one lap in Portugal when they eventually gave us a proper Judd engine,” Maurizio says with a beaming grin. “Imagine that in two weeks we had rebuilt the car, changing from the W12 to the Judd engine, managed to survive the motor swindle, and eventually pull one single qualifying lap. The chief mechanic of the team who sold us the motor came and shook our hands as, his words, we had accomplished an impossible mission. That day we earned the respect of a few other teams that were obviously in much better condition.”

Reflecting on his time with Life, Maurizio wears entirely rose-tinted glasses.

“We were certainly an oddball,” Maurizio recalls. “When we left for Portugal we had just finished parts for the Judd-powered car. We were on the same charter plane with Ferrari, Minardi, and Lamborghini. Our carry-on luggage were radiators and parts of the car, parts of the piping radiators. The night before the pre-qualifying in Portugal, our car in our pit box looked like a Tamiya kit.

“It was a fantastic human experience. I mean completely crazy. The whole thing was completely, totally, crazy,” he says. “We were like the Blues Brothers when they’re chased by the police. We were on a mission, that every two weeks, we had to put together the car, and try to make our best. We knew that we were nowhere near pre-qualifying, and that almost inevitably, the car would end up, before the end of the pre-qualifying time, broken.

“By Friday at 10:00am we were free, because our job was done. And the plane would have been probably Monday or Sunday anyways. So in Mexico, for example, after we finished with the pre-qualifying, we went to Teotihuacán. Earlier in the season we rented a BMW in Italy and slept in it on our way to Spa. I mean if you’re 20-something and working with a Formula One team, then why not?”

This, more than anything else, is the spirit of Life F1. A ragtag privateer team of mechanics working anywhere, anyhow, and indulging in their own vices away from the track, attempting to live the romance of ’60s grand prix racing three decades too late. Not even F1 veteran Giacomelli was immune to rolling his sleeves up and joining the team spirit.

“We were in Monte Carlo for the grand prix, and we were setting up the car on the dock of the marina,” Maurizio explains. “The factory had forgotten to properly assemble the trumpets on the engine, and so we had a rented scooter, and Bruno took me to a place he knew and he personally worked on the lathe machine to create the missing washers. Can you imagine anyone today driving in Formula 1 who is operating a lathe and cutting pieces to finish the engine? Bruno was always happy despite the fact that we were becoming sort of a joke in the paddock. But he’s always been with us, supporting us, and helping us in any way that he could.”

Not everyone was willing to play their part, particularly the team’s first driver Gary Brabham – arguably the least gifted of the three sons of Australian racing royalty, triple World Champion Sir Jack Brabham.

His two brothers Geoff and David were also making their way up the racing ladder in ’90, and Gary was hoping to be the first of his siblings to follow in the footsteps of their legendary father and race in Formula 1, accepting the Life gig on the guidance of 1980 world champ, Alan Jones. While he would race elsewhere following his stint with Life, Brabham claims those two races were enough to essentially kill his life as a professional racing driver.

“It was a bit of a disaster to put it that way. It basically stuffed my career if you really look at it,” he tells MOTOR. “I made an emotional decision because I wanted to get to Formula 1, rather than a business decision.”

Brabham quickly realised that being an F1 driver at Life wasn’t going to be anything like his lofty expectations.

“I was staying with my brother, Geoff, in Florida, and got a phone call,” Brabham says. “I got word through that they doubted very much that the team was going to arrive. The car might be there [in Brazil], but maybe nobody else. I had no money, absolutely no money and I shared a taxi with Alain Prost to get to the airport, which he paid for, luckily. And then I was eating from the Benetton hospitality suite as that was the only way I could eat.”

It’s hard to feel too sorry for Brabham. In later years he was convicted of a number of serious sexual offences against children, for which he was incarcerated. His part in this story is just another example of how when you begin to inspect the legend of Life F1 beyond the surface level observation that it was a comedy of errors, it twists itself into stranger knots than you could have ever expected.

Then there is the enigma of the man behind the entire project, Ernesto Vita. During the 1990 season Life had become such a joke within the F1 paddock that Bernie Ecclestone tried to intervene. The iron-fisted leader of F1 – who had led a coup by the teams to earn his position as commercial rights holder – held a private meeting with Vita and Rocchi, attempting to convince them togive up on the rest of the season. Vita declined.

Despite having no funds, questionable levels of equipment, and his car being a constant rolling roadblock, Vita said no to Ecclestone, the hardest bastard in global motorsport. That was the kind of bloody-minded character he was.

“Vita was best salesman that you could ever think of,” explains Maurizio “But if you read his interviews now that he gives from time to time, he takes reality and mixes it with made-up stories and makes you believe this is the truth.

“There are no grey shades with Vita. It’s white, black, white. He was, how to say, hypnotic. The amazing thing about Vita was that he could literally sell ice to the Inuit, it was unbelievable. But for the rest, it was definitely not the best manager ever for a project like that. But he was able to start it, and that goes to his credit.”

There’s remarkably little on Vita available on the public record. He seemingly appears out of the ether in 1988, before disappearing again once the Life project imploded.

“Ernesto Vita, most of anything else, was a dreamer,” Giacomelli reflects. “In a way he had some good ideas, but mostly he was a dreamer.”

While Vita’s compatriots skirt around his more chaotic personality traits, Brabham clearly has an axe to grind. “He was very volatile. He had a temper on him,” the Australian recalls. “When the team sat down with him to tell him I don’t have any sponsorship, I was waiting outside and he cracked the shits and tipped a table over.”

A profile in French sporting magazine L’Equipe exposed Vita’s fickle personality when he was asked by a journalist how the team could benefit from post-race debriefs. “Briefings, why? We have nothing to discuss,” he is quoted as saying. Adding: “It’s better not to pre-qualify, we haven’t got any spare parts left”.

While the merry band of misfits were those enjoying themselves on the road, and it was Vita who willed the team into existence in a misguided attempt to make a quick buck, it was Rocchi whose vision and engineering intellect became the foundations that the entire project was built upon.

Foundations, it turns out, that were about as stable as sand. By reputation, Rocchi was a master engine designer, and the lure of working alongside a living legend was what drew many to the Life project. But in his old age he had also become careless. While his W12 design was impressive in theory at least, the Italian maestro had made one fatal flaw in his development of the real thing.

During bench testing he encountered an issue with lubrication of the daughter rod bearing for the middle cylinder bank. “In order to solve that problem, Franco drilled a small hole in the area where the main rod had contact with a daughter rod in order to bring some extra oil to the daughter rod,” Maurizio recollects.

This ‘solution’ became the source of nearly all of the team’s many, many mechanical woes during the 1990 season. Since then, Maurizio and Piazzi have taken upon themselves to carry on Rocchi’s work – tinkering away in home workshops to find a solution.

“We focused on a single cylinder bank and found 30 horsepower, which extrapolated across the two other banks would have resulted in a total of around 560, 570 horsepower rather easily,” Maurizio explains. “Consider that the Judd engine had around 600 horsepower, but this was a very basic development that we had. This is our big question mark. What if? What if we had the money?

What if we had the knowledge of today, that we have gained through years of experience? A lifetime of experience. What if?”

“Believe me, with more time and more money, I cannot say that the engine would have been able to rev to 13,000rpm, and make 700 horsepower. Nobody can say that. But I’m quite convinced that with the time and the money, the engine would have been reliable, and decently powerful.”

The reputation of Rocchi’s design is a topic that prompts an impassioned response from Piazzi, who to this day remains dedicated to the Life project.

“It was not a joke of an engine, it was not the idea of a lunatic,” he says emphatically. “It was just at the wrong time, probably late for its age.”

Both Maurizio and Piazzi hold onto the fact that with enough funding they would have been able to change history just enough for someone else to be left holding the unenviable label of Worst F1 Team In History. Though, that view of things conveniently omits the fact that Rocchi’s W12 wasn’t Life’s only burden.

All the romanticism in the world can’t cover for the fact that even with the Judd V8 the team languished behind the rest of the field. Despite the new engine, Life were still dreadfully slow in Jerez, with Giacomelli falling 18 seconds short of the pre-qualifying cut-off time. This was in no small part because the chassis was the heaviest on the grid, weighing 30kg more than the minimum requirements when fully assembled.

Following that on-brand performance the inevitable finally happened, and the Life Racing Engines team disbanded. Vita had no more money, no more tricks, nowhere to go but into the arms of a failure that had haunted him for 18 months. There was no sombre team meeting. No last hurrah. One day Piazzi, Maurizio, Giacomelli, and the entire Life family just… stopped.

When the 1990 season was over, Ferrari let the team conduct a test at Fiorano – a remarkable change of heart following a silent grudge earlier in the year when Vita had claimed in the press his new team would put Maranello’s fame in the shadows. It seems preposterius now, but his prophecy did come true in a way, with Life’s woes remaining an unbeatable high-water mark (or is that low?) for poor performance by a red Italian car in F1.

Life Racing Engines lives on in infamy. History has not been kind, and more than three decades since its sole season in Formula 1, the internet is littered with blog posts and comments about ‘the worst team in racing history’. Most of them are wrong.

Not because Life was actually good – it patently wasn’t – but because they entirely miss the almost surreal back story to one of Formula 1’s last truly privateer efforts.

The final twist in the Life story happened after the turn of the century when Lorenzo Prandina took ownership of the car and engine. The French collector has an affinity for unloved and unsuccessful machinery from racing history and commissioned a full restoration of the car by Piazzi.

This culminated at the Goodwood Festival of Speed in 2009, when both the Life L190 and Ayrton Senna’s 1990 championship-winning MP4/5B (which won six grands prix that year in the Brazilian’s hands) were present. During the event, the McLaren was towed back to the pits with a broken diff, while the Life completed a pair of successful runs up the hill – using the same camshaft that was fitted when it raced in Monaco. Such is Life.

How to make your very own L190

To build an accurate Life L190 start with a trio of four-pot cylinder banks, arranged 60 degrees apart with a bore of 81mm and a stroke of 56.5mm, for a total capacity of 3493cc. Set the redline to 12,500rpm and the compression ratio at 13:1. Fuel injection and ignition is to be sourced from TDD with spark plugs from Champion.

Lubricating the engine is oil from Agip. The chassis uses double-wishbone suspension at each corner, with pushrods activating Koni dampers. A wheelbase of 2780mm makes the L190 one of the shorter cars on the grid, while 1810mm/1657mm tracks front/rear are on-par for the style of the time. T

he W12 transfers power through a home-built six-speed manual gearbox with Hewland internals and an AP clutch, to Goodyear slick rubber. Stopping everything are Carbone Industries brakes and Brembo pads, while a 200-litre fuel tank is supplied by Pirelli.

Secan radiators help maintain temperatures, Stack instruments inform the driver of vital information, while Pignone e Cremagliera is responsible for the steering. Put it together and the engine should weigh 154kg, with the total car tipping the scales at 530kg.

Those who dodged a bullet

Life’s tornado of disaster nearly claimed the scalp of a double world champion

Giacomelli wasn’t Vita’s first option to replace Brabham. He claimed at the start of the season to have an option on Bertrand Gachot’s services, before trying to get Bernd Schneider to join the team. The German touring car ace drove for Footwork at the opening round, but had no intention of taking Vita up on his offer.

“I will not be driving for the team. I have received a fax here in Suzuka inviting me to go and visit the factory, but I definitely don’t want to drive for them,” Schneider told media at the time.

Rob Wilson was then sounded out for the role. He declined, and instead went on to become the most influential driver coach in the world, with pupils such as Juan Pablo Montoya, Kimi Räikkönen, David Coulthard, Marco Andretti, and Valtteri Bottas.

Vita’s biggest whaling attempt would come later in the year when he tried to convince Mika Häkkinen to test the car. Unsurprisingly, the Finnish youngster declined.

“I don’t know why. It was such a good opportunity for his career,” Maurizio laughs.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesRemembering the 1994 Formula One Season

Euphoric highs and crushing lows – the 1994 Grand Prix season had more plot twists and drama than a modern box-office smash. To mark 25 years, we hear from those who lived it

-

Features

FeaturesThe saviours of Formula 1

Meet the men tasked with bringing Formula 1 into the digital age. One is well-known to racing fans, while the others... well, the others are American. Here's their plan.