For more than 50 years, Fishermans Bend was a dream factory.

The dowdy industrial suburb in the working-class Melbourne docklands was the home to Holden – the cars and the brand and the people – as it produced the vehicles that put Australia on wheels.

The long honour roll at Holden began with Laurence Hartnett, who helped plan the car that would become the original 48-215, and includes managing director Chuck Chapman, legendary designer Leo Pruneau, suspension guru and then managing director Peter Hanenburger, and Tony Hyde on the engineering side.

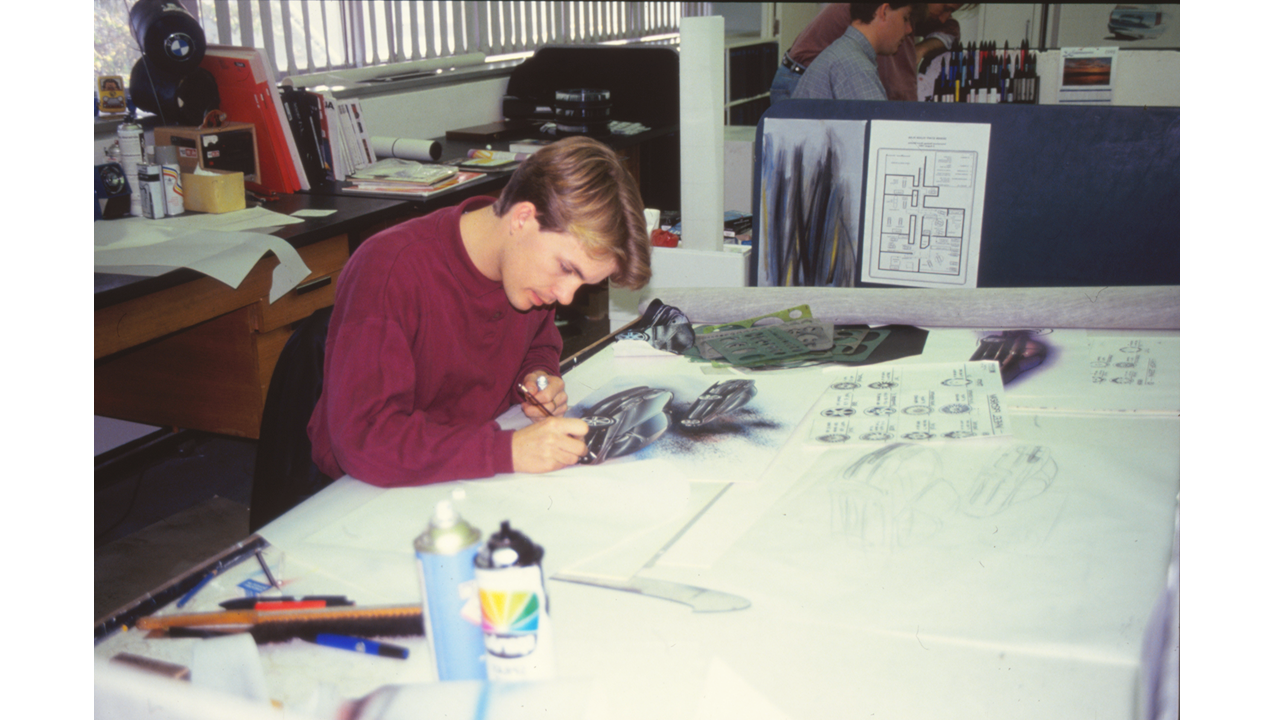

It was into this hotbed of local innovation that Peter Hughes arrived in 1990 after a personal invitation from Michael Simcoe – now the outgoing global head of design for General Motors – to come in for a chat.

“The first couple of months were terrifying,” Hughes begins. “I just thought I was totally out of my league. There were so many talented people going in and out of that joint. I was trying not to be embarrassed by what I was doing. But you soon realise the other young guys are no worse than you.

“There were a lot of talented people in that era, but no more talented than the people who came before us. We wanted to make a difference and make Holden great again. I adored Holden and felt part of it.”

But Hughes didn’t begin that way.

Born in Melbourne in 1966, to Bill and Carol, his father was a talented rally driver who worked in aeronautical engineering. Young Peter had a replica race suit at age four and would go to events to watch his dad. The family had a Valiant Safari wagon as a daily driver, and there was interest in Alfa Romeos and BMWs, but not Holden.

“Holden, for me, was the brand I would never be seen in,” Hughes laughs. Little did he know.

“I loved drawing at school so you put two and two together. I did Year 12 and then went straight into industrial design at RMIT. A lot of Holden Design people went through there, like Richard Ferlazzo and Jenny Morgan. Every project I did was automotive.”

But not everyone was a fan.

“One of the first lecturers was ex-Holden and he told me to stop drawing cars, because it was too hard to get into and I was not good enough. That really pissed me off.”

It lit a fire that still burns today.

Out of college he got a job at CS Tooling, which was doing a bunch of stuff on the aftermarket for cars including the Commodore. When Peter Brock parachuted out of the Holden Dealer Team, the new owners got Hughes to work on an ‘Aero’ package for the VN Commodore in 1988 and it was a star car at the Melbourne Motor Show.

“That’s how I met Brock for the first time,” Hughes recalls. “I was having a Winfield Blue and an instant coffee out the back and Brock said ‘Who’s designing this?’

“I came in, shook his hand, and within 30 seconds he captivated me. I was lost. Mike Simcoe and Phil Zmood also saw it. Simcoe used to wander upstairs at CS and look at my sketches but he was just another guy with long hair, like me. Then I got a phone call and he told me to come in for an interview.”

It was the start of a giant love affair.

“I was there for 30 years exactly, from 1990 to 2020. It was fantastic. We were very, very, very fortunate to go through the place at that particular time. For one thing, we ended up having Mike in charge and he was very driven. So we got to work on some very special programs. He was driven to succeed and a great leader, so we all followed him along that path.”

He began at the bottom, however, working on the back-end styling of the VR Commodore.

“I had some understanding of the Australian landscape, but I loved Alfa and Lotus, I cannot lie about it. I was looking at the VL on the road so the drive was to make Holden cool.

“I wasn’t a big fan of looking backwards. I never looked into Holden’s history. We were looking at what Audi and BMW and Mazda were doing.”

What was it like, day-to-day?

“You can only reflect on it later. The place was about doing more with less. And we were proud of that. All Holden’s programs were driven by budget and a business case based on volume. On the flipside of that, we always revealed cars that looked a lot more expensive than they were. We were pretty proud of that side of it.”

The leadership of Simcoe was key.

“Mike wouldn’t say how great a car was. He would let others say that. That’s the sign of a great leader – one confident enough not to take the limelight.”

But so was Hyde, who helped with Simcoe to lay the foundation for the born-again Monaro, codenamed V2.

“That project was done on Sundays, in my own time, in the studio with some other guys. It was never designed as a show car. It was a rolling concept car. Tony gave Mike $300,000 to do a rolling prototype. Imagine doing a Holden Coupe again.”

But there were also everyday Holdens, and some side work on Elfin sports cars, as well as the hero cars for shows – Holden Coupe, Utester, Sandman, Coupe 60 and even a Suzuki that became the Holden Cruze.

“That was a great time. It’s a wonderful feeling. It was addictive. You went back into the studio and tried to come up with the next one.”

“You get tagged to cars. I’m obviously tagged to VT, VT Monaro and VE. The most influence I had on any one car would be VE. By that stage I was old enough to play the game, so I knew what Mike would like. I had quite a big ego, so by the time VE came around I made sure I would not lose the pitch.”

But Hughes was not just hidden behind the security screen at Fishermans Bend.

“I did many stints in Japan, including a couple with Suzuki on shared programs. Later on, also at Isuzu on a next-generation Colorado that never happened.

“I had big blocks of time at Korea. Mike used to call me ‘Mr fixit’. I was walking into Korean studios and upsetting people. But within the first couple of days you would hack into something and make it better, and you got them onboard. It was nice to help people get their designs come to life. And there were lots of noodle dinners in the back streets of Seoul.”

There were trips to the USA as well, but Hughes never craved a full-time overseas gig.

“Every time a posting came up it was bad timing. I wasn’t wired like guys who were unconditional on career. I valued lifestyle and keeping my wife happy.”

But the good times could not go on forever and, when there was growing pushback on projects including a next-generation Colorado, Hughes could see the end at Holden.

“That was when I knew it was over. They didn’t want us to survive. I was putting a plastic bumper and a set of wheels onto a car that was already behind. I was spiteful and angry. I knew the end was coming. The only thing we didn’t know was how quickly.”

There was still some hope, but Hughes was one of those who could not stay to the end. “There are all different stories. You had the crew who honestly believed it would never shut. After production ended we were still viable, doing Cadillacs, and Buicks. We were doing lots of things. We were an outlet for overflow. Most people within Holden Design honestly believed we would have a future.

“There was a section who were more sceptical, and I was one of those. So I organised Plan B, which was to go out on my own. Because of my attitude, I was in the first group to leave. I wasn’t helping anyone. I was happy to say goodbye. I didn’t want to hold on for any longer.”

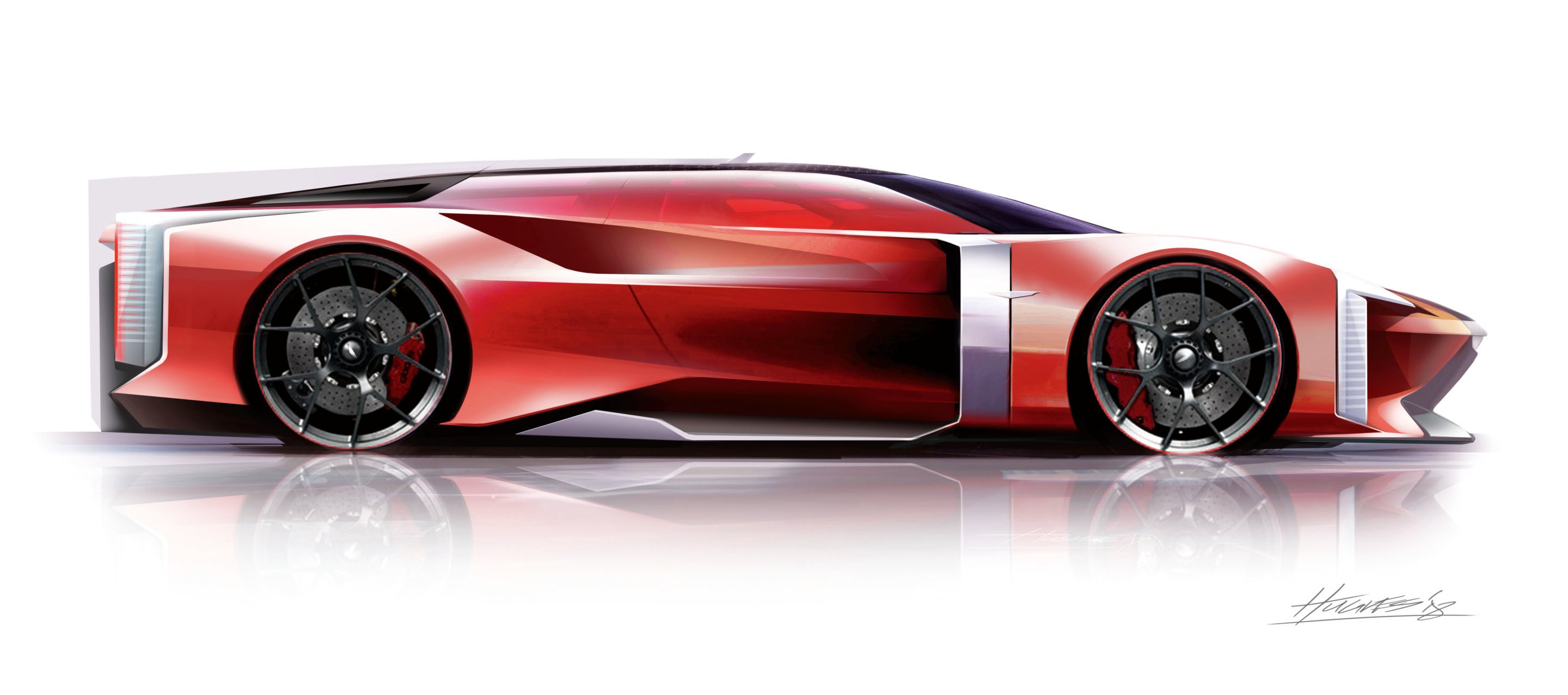

The end of Holden Design was just another challenge for Hughes, who pivoted into designing and production of limited-edition posters of classic road and race cars – Holden at first, then Ford and even Mazda – and a growing amount of livery work for race teams.

He is the one charged with making an impact on track and on television, while also satisfying the dizzying and conflicting requirements for sponsors of racing teams in Supercars – led by Triple Eight and Walkinshaw Andretti United – and even NASCAR in the USA.

“When Holden shut, everyone wanted a piece of the nostalgia. I made a fair bit of money in the first couple of years. I had my little business selling prints for about five years. I was doing lots of motorsport stuff, which I enjoyed.”

He is closing on 60, works from a home studio, and has a car collection including a Lotus Exige and a 1971 Alfa Romeo Spider.

“I reckon I’ve still got a good decade me. Mike used to say there is no age limit to good design. You have got to keep stretching yourself. Reinventing the role and doing new stuff.”

So, how does he look back at his three decades with Holden.

“My thoughts now are grateful. I got to design a Holden. I got to work on everything. Looking back,

I cannot believe what I did. I was always busy. Ah, good times. Great times,” he laughs as he signs off.

This article originally appeared in the June 2025 issue of Wheels magazine. To subscribe, click here.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesThe Wheels Interview: Meet Kees Weel, the knockabout Aussie who cools Formula 1 cars and satellites

They call him 'the radiator man' - Kees Weel is a Dutch immigrant who discovered he had a way with car radiators and has now built a $1 billion Aussie business providing cooling solutions to an amazing array of high-profile clients.

-

Features

FeaturesThe Wheels Interview: Ride king Graeme Gambold makes cars 'fit' for Aussie conditions

Graeme Gambold has established a reputation as the go-to man when manufacturers want a car that'll handle Australian conditions

-

Features

FeaturesThe Wheels Interview: How Bernie Quinn's Premcar solves problems for some of Australia's most popular makes

Bernie Quinn was an underperforming, self-confessed ‘battler’ before he found his feet as an engineer at Ford. These days he’s the CEO of Premcar, a company he has built up with a former colleague to create uniquely Australian answers to a variety of automotive questions.