First published in the July 1979 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

Do the Falcon 5.8 and Commodore 5.0 manuals put the punch back into performance? You’d better believe it. Of course in these silly speed-limited, responsibly fuel-conscious times the fiery thirsty big bangers are slightly anti-social and becoming more so almost by the day. On the other hand, it’s one of your last chances to have a damn good, really exciting fling. Before very long it’ll be true that they don’t build ’em like this any more.

The very last of the hairy-chested road rockets … that may well be how the manual 5.8 Falcon and 5.0 Commodore are fated to go into history. Enthusiasts’ only consolation is that the swansong’s being played on high and strident notes. For the moment, at least, High-Performance is alive and well and living in the four-speed, many-litred, bent-eight Falcon and Commodore. So let’s revel while we can.

Looking forward to the next major model changes in 1984-85, it’s difficult to foresee another generation of the blatantly and excitingly and thirstily V8 versions. It’s inevitable that rising petrol prices must spell extinction for big-banger sports sedans.

That such cars are an endangered species is obvious when one considers how their ranks have thinned so much in recent years. The toll reads like a Who’s Who (or rather a What’s What) of the high-performance world. Among them are the local supercars that stormed their ways into Australian motoring folklore – the Falcon GTs, the Holden Monaro 350, the Chrysler Charger R/T, and the SL/R 5000 (or A9X and L34) Torana. Mighty, Magic, Muscle Cars – Australian style.

There’s nothing like them among the Japanese and very few Europeans offer their sort of performance either; a few sports and GT models and a handful of sedans, starting at Very Expensive and going up in price from there. And the Americans aren’t in the hunt any more either.

So if it’s performance you want – in the good old neck-cricking, breath-sucking, gut-knotting way – and the handling to go with it, then the Falcon and Commodore manual V8s are the place to get it. They’re for drivers who like wielding the big whip; for drivers who can appreciate and use a power of performance. And to hell with the fuel economy … well almost.

To some they’re too fast and too thirsty, these big muthas. Wowsers see them as anti-social. But what they are is anti-ordinary, and a couple of blows for strong-willed individuality can’t be bad.

Ford and Holden have been hard at it now for more than a decade. locked in stirring combat so it’s only fitting that they should build the last of their kind.

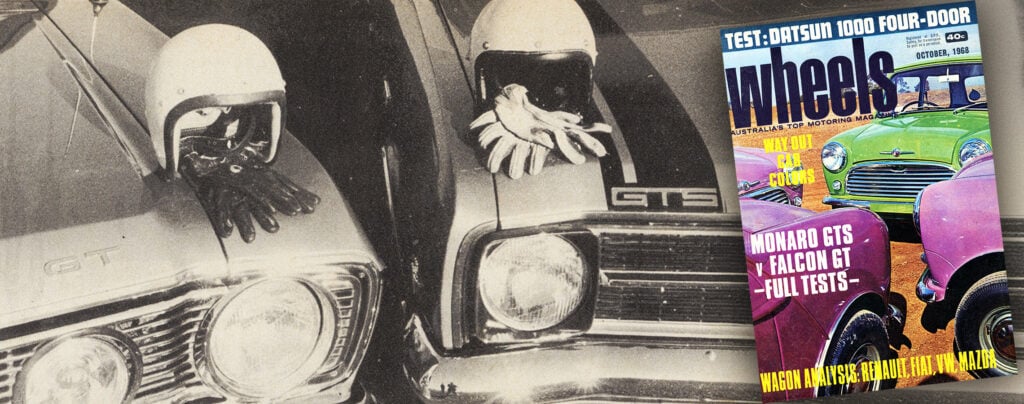

Henry started it in 1967 by releasing the then awesome XR Falcon GT. The big Roarin’ Fordie was tantamount to a declaration of war. The shock waves were still echoing from the top of Mount Panorama when the General rolled out his heavy artillery – the Monaro GTS327. No other maker could muster the firepower to enter the ring, let alone mix it with Ford and Holden. Only the respective models changed, through the GT (and GTHO) series on one hand, and the Monaro (and then Torana) on the other.

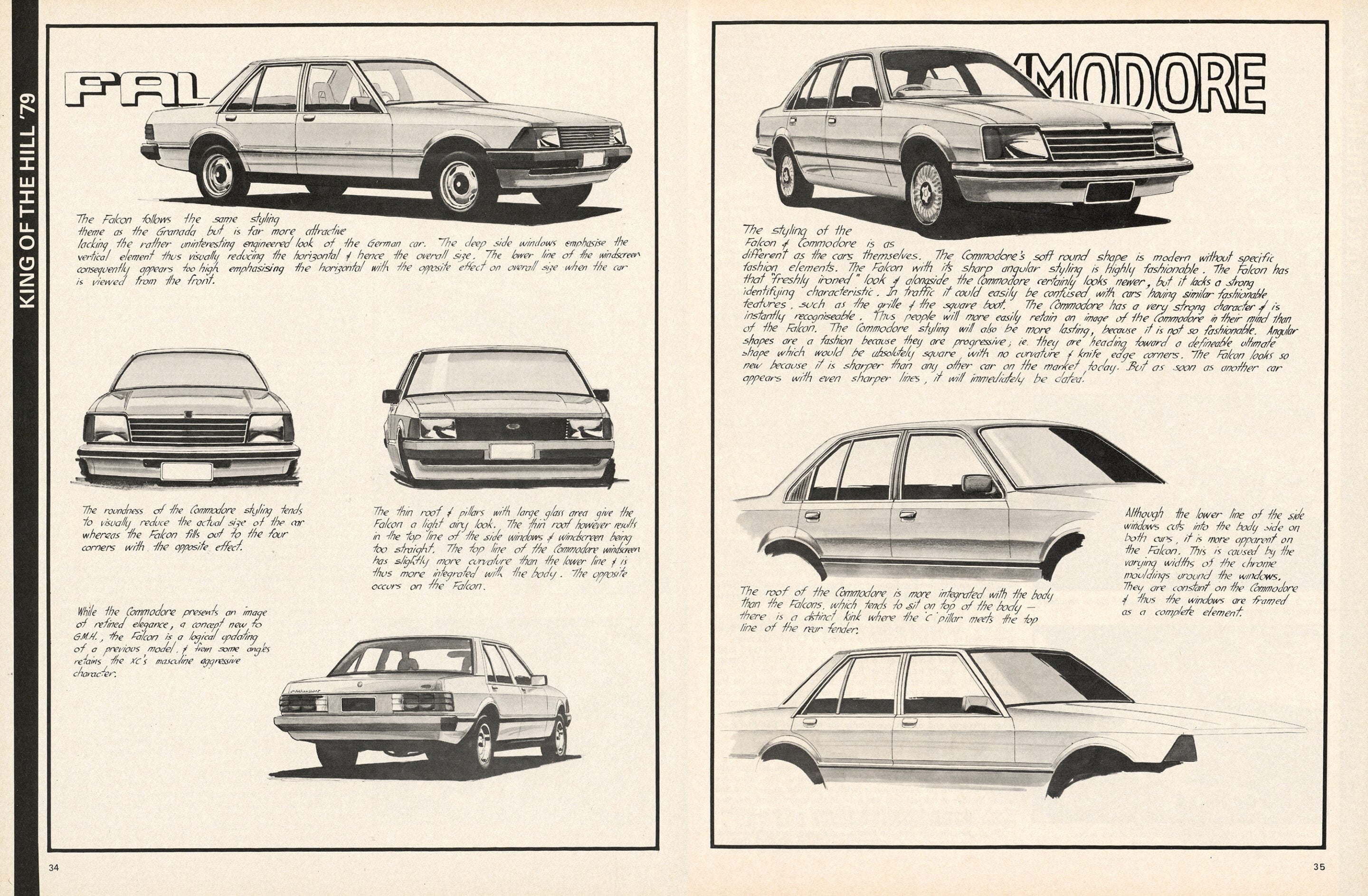

Now the scenario has changed. The script remains the same – performance v performance – but the models are new and have brought a subtle shift in emphasis. The current contenders have “brain” as well as brawn, and are much better for it. Just as the Falcon XD is a giant step forward from the XC in many ways, so the Commodore is that much ahead of the late great Holden GTS.

The GTS had been uplifted from ordinary to excellent performance standards (with Radial Tuned Suspension) when we pitted it against the Falcon GXL in Wheels January, 1978, for the original King Of The Hill comparison. Both were pretty reasonable performers by the ADR-depressed standards of the day, though not in the same mould as their rorty old ancestors. The GTS did the 0-400 m in 16.8 seconds and the Falcon in 16.3 seconds, a far cry from the days when GTs and GTSs used to crack 15s for the quarter mile. The Commodore and XD Falcon don’t step into the old-timers’ boots either, but are more sure-footed on their own accounts anyway … all the better for climbing the hill to kingsmanship.

Pricing

What’s in a name. The Falcon GT by any other badge would perform as sweet. That’s proved by the new model regardless of its GL label. The GT officially died in XB form in 1976, and the closest thing to it in the XC series was the Fairmont GXL with 5.8-litre V8. four-speed manual gearbox, four-wheel disc brakes and selected other options.

For the latest comparison we stepped into a Falcon GL, the price of which started at $6600 and wound up at about $8800 when the high performance running gear and a few more niceties were added. If you didn’t want all the trimmings you could in fact have the muscle-built Falcon for about $8090, at which the spec includes 5.8 engine, four-speed manual gearbox, limited slip diff, four-wheel disc brakes and ER70H tyres. At that level the Falcon has to be the market’s best value package on performance per dollar basis.

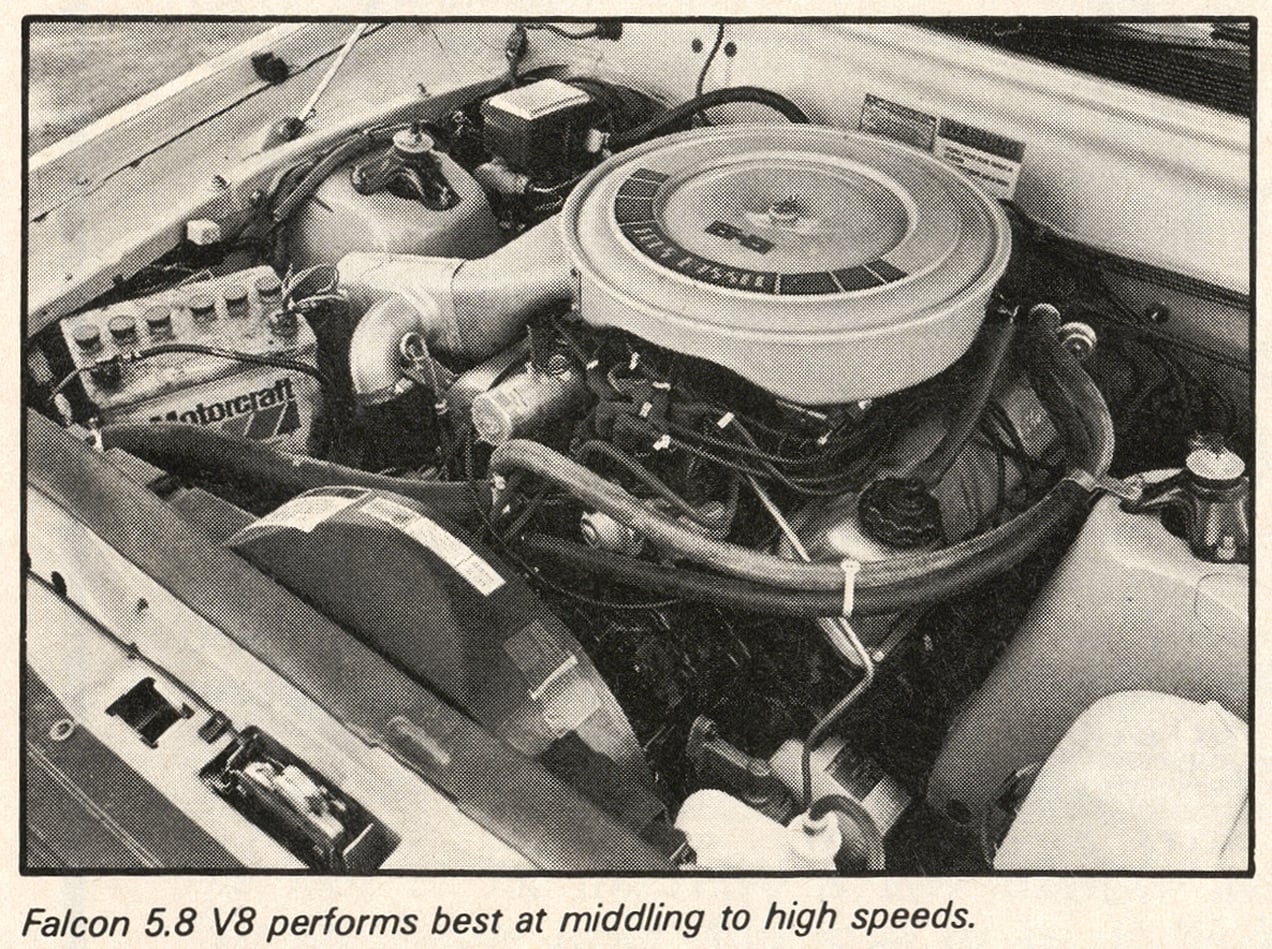

For icing, the test car also had rear inertia belts ($43), tinted windows ($35), laminated tinted windscreen ($106), Volante mag wheels ($163), and the $361 “S” Pack which includes comprehensive instrumentation, digital clock, intermittent wiper control, striped fabric for the seats, left-hand outside mirror, front bib, long-range driving lights and distinctive paintwork (meaning side stripes).

The “S” Pack option also claims to include ER70H14 tyres, which means that the $8798 price quoted for the test car doesn’t quite compute according to the way we see the figures. If there was an inadvertent duplication of tyre price in the base 5.8 spec and the “S” Pack, the test car’s price would add up to $8728, making it even better value. However we wouldn’t be prepared to wager on that because Ford’s mixture of standard items, options and mandatory options needs very careful cross-referencing. If we were buying an extensively-optioned Falcon we’d want to itemise everything individually to avoid the risk of being double-billed for anything. It could happen.

No such room for confusion existed with the Commodore because it was a much simpler package, albeit considerably more expensive than the Falcon. The test car’s tag started at $10,828 for the 4.2-litre SL/E and rose in one self-contained $366 jump to $11,194 with the dual-exhaust 5.0-litre engine, close-ratio four-speed manual gearbox, and rear speaker. Helping account for the difference in price (against the Falcon) were the SL/E’s headlight wash/wipe system, locking fuel cap, electric antenna, velour headlining, AM/FM radio-cassette, power steering, air conditioning, remote control boot lid, driver’s seat height adjustment, and bumper overriders.

Performance

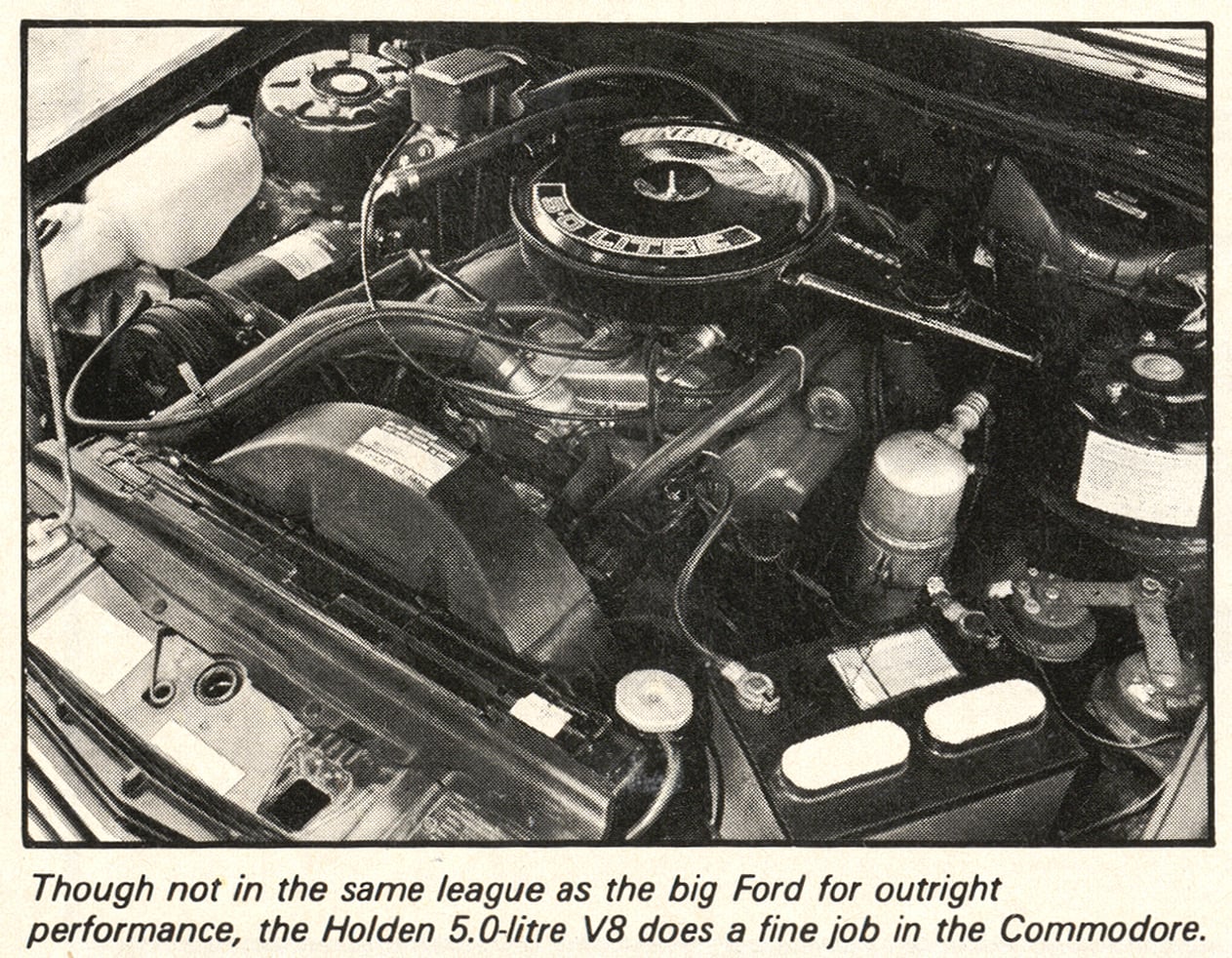

There’s no doubt that the Falcon has the muscle and the legs. That it confirms the old there’s-no-substitute-for-cubic-inches saying was borne out in the performance tests at Castlereagh Dragway.

The Falcon had already been well used by the motoring Press by the time it reached us, and was in a fairly ordinary, nothing-special state of tune. It had the usual roughly lumpy idle we’ve come to expect from the 5.8 engine in ADR 27A guise, shaking the whole car at standstill, as though impatient to be on its way. It also had the 5.8’s usual bad habit of sometimes violently running-on when the ignition was turned off immediately after very hard strops.

The XD re-affirms the Falcon’s status as king-of-the-quarter, or the 400-metre-beater, by storming along the dragstrip in breath-taking style. Today there’s only a handful of standard sedans anywhere in the world that can turn sub-16s for the standing 400m. The 5.8 manual Falcon does 15.8 so consistently that we’ve no doubt it could knock several tenths off that time given attention to engine tune, tyre type and pressure, and more practice runs to find the optimum gearshift points. That it runs so quickly so easily, straight out of the box, speaks volumes for its muscle.

The Commodore is no slouch either and gets under the mid-16s in spite of being a lot slower than the Ford in its initial surge from the starting line. The Ford got its power down onto the ground quicker than the Holden which lost 0.4 second to 50 km/h. Try as we might, we couldn’t reduce the deficit. Lots of revs brought lots of time-wasting wheelspin. But more moderation on the loud pedal meant a relatively slow start anyway. So it was stuck with that initial lag. With the Falcon though, it was just a case of grip-and-go.

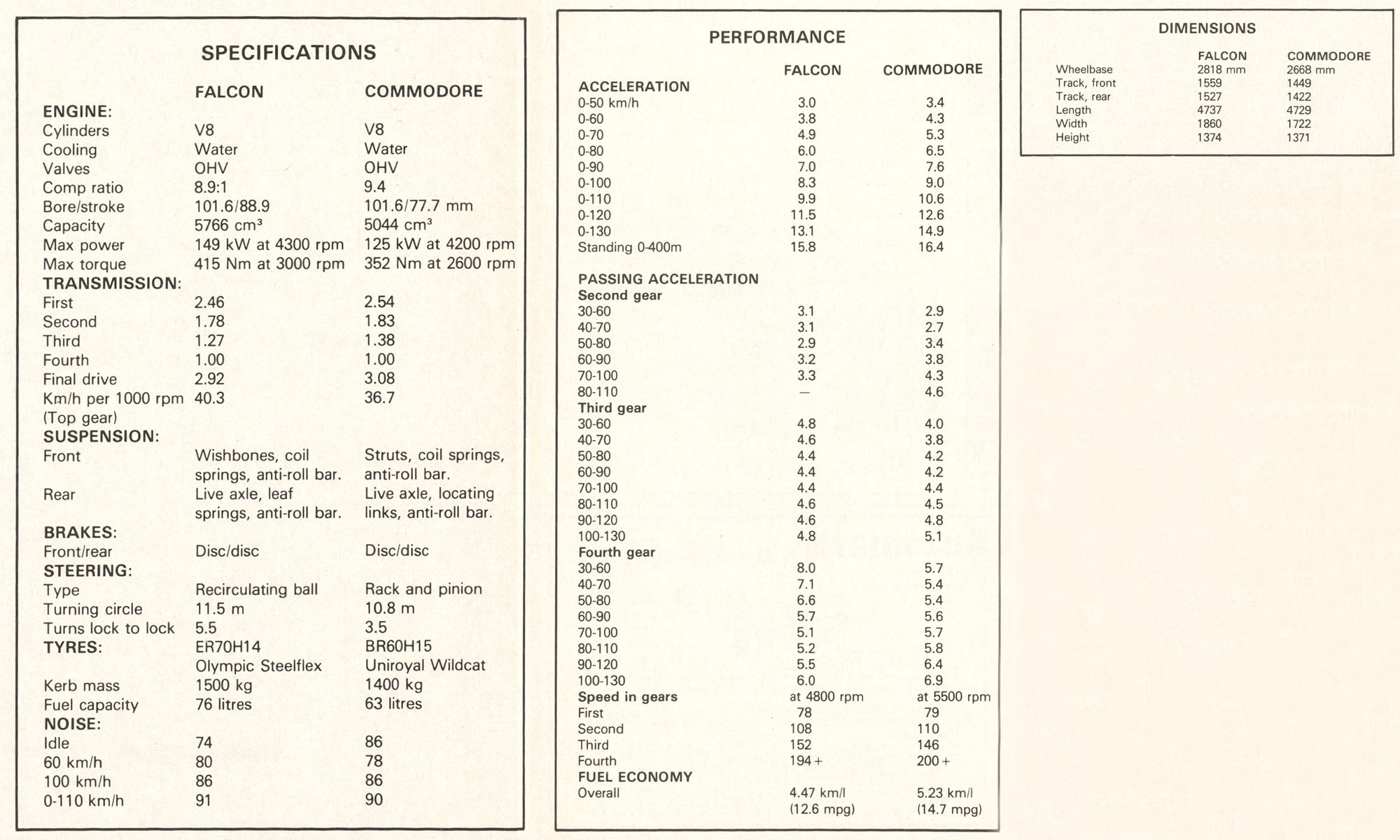

The Commodore shone with outstanding in-gears acceleration from low to middling speeds. It was impressively responsive and flexible in the first three or four overtaking brackets where it headed the Falcon by comfortable margins. In third and fourth gears the Ford doesn’t really get into stride until it’s doing 80 or 90 kays, then – pow – it flies.

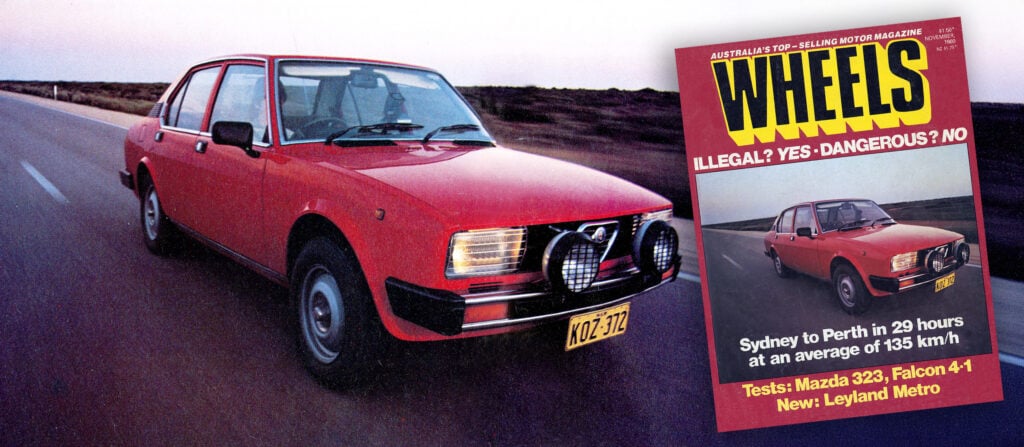

Top speeds are pretty academic these days, but purely in the interests of science and accurate reporting we took the big V8s up to their respective red lines in fourth. In the Falcon that was 4800 rpm and 195 km/h; in the Commodore it was 5500 rpm and 202 km/h. The Commodore was flat at that speed. The Falcon could have gone faster – we saw 5300 rpm on the tacho during one burst coming back from the Flinders Ranges.

The thing that counts, of course, isn’t that they’re capable of such high speeds but that they can cruise so effortlessly and safely at the

legal limit, which in most places means they’re bopping along at only half their potential.

Fuel economy

One should almost bite one’s tongue for mentioning these cars and fuel economy in the same breath. The manual V8s are bought because they perform. And when you do the natural thing and flex their bulging muscles, they get very thirsty.

You know the old saying about watching the fuel needle fall … well, with the Falcon particularly it’s almost true. The much-touted electronic fuel gauge is a fairly useless thing anyway and (on a couple of other Falcons we’ve so far driven so far) gives wildly variable readings. It’s a bit of a shock to see the needle (between its spasmodic accelerating/braking/cornering/climbing/descending fluctuations) go sliding downwards, slowly at first, then increasingly quickly once it passes the halfway mark.

For a hard-driven distance of 653 km, which included all the performance tests, the 5.8 manual averaged just 4.47 km/l (12.6 mpg) from a best of 4.99 km/l (14 mpg) to a worst of 4.2 km/l (12 mpg).

The Commodore did a bit better by averaging 5.23 km/l (14.7 mpg) from extremes of 5.5 km/l (15.6 mpg) down to 5.0 km/l (14.2 mpg). So it wasn’t exactly frugal either. Remember, though, that it had air conditioning and power steering to add to its consumption. On the other hand, this was the SL/E that had earlier been tuned for, and competed in, the 1979 Total Oil Economy Run. Its consumption in that event averaged 8.14 km/l (23 mpg), showing what it can do when prepared and driven specifically for economy. But that’s not what manual V8s are bought and used for.

Transmission

Not much difference here on paper – both have manual floorshift gearboxes with synchromesh on all four forward [gears]. The ratios are similar too, with the Falcon just a notch or so taller in one, two and three. Neither of the test cars was quiet in the transmission. Gearbox growls and whines were audible in both cars, more so in the Commodore, though not objectionably loud.

It’s in the gearshift that the Falcon and Commodore transmissions are clearly different. The Commodore has an easy change with what feels to be relatively long throws from point to point, giving light but fairly loose shifts. The Falcon’s shift was preferred by all our crew for it is as light as the Holden’s but with shorter and crisper throws so the lever can be snicked from gear to gear probably as nicely as you could wish in a big car.

Curiously, while the Falcon is (and feels) that much bigger than the Commodore all over, its lever has a smaller knob which unanimously rated second with our drivers.

Handling

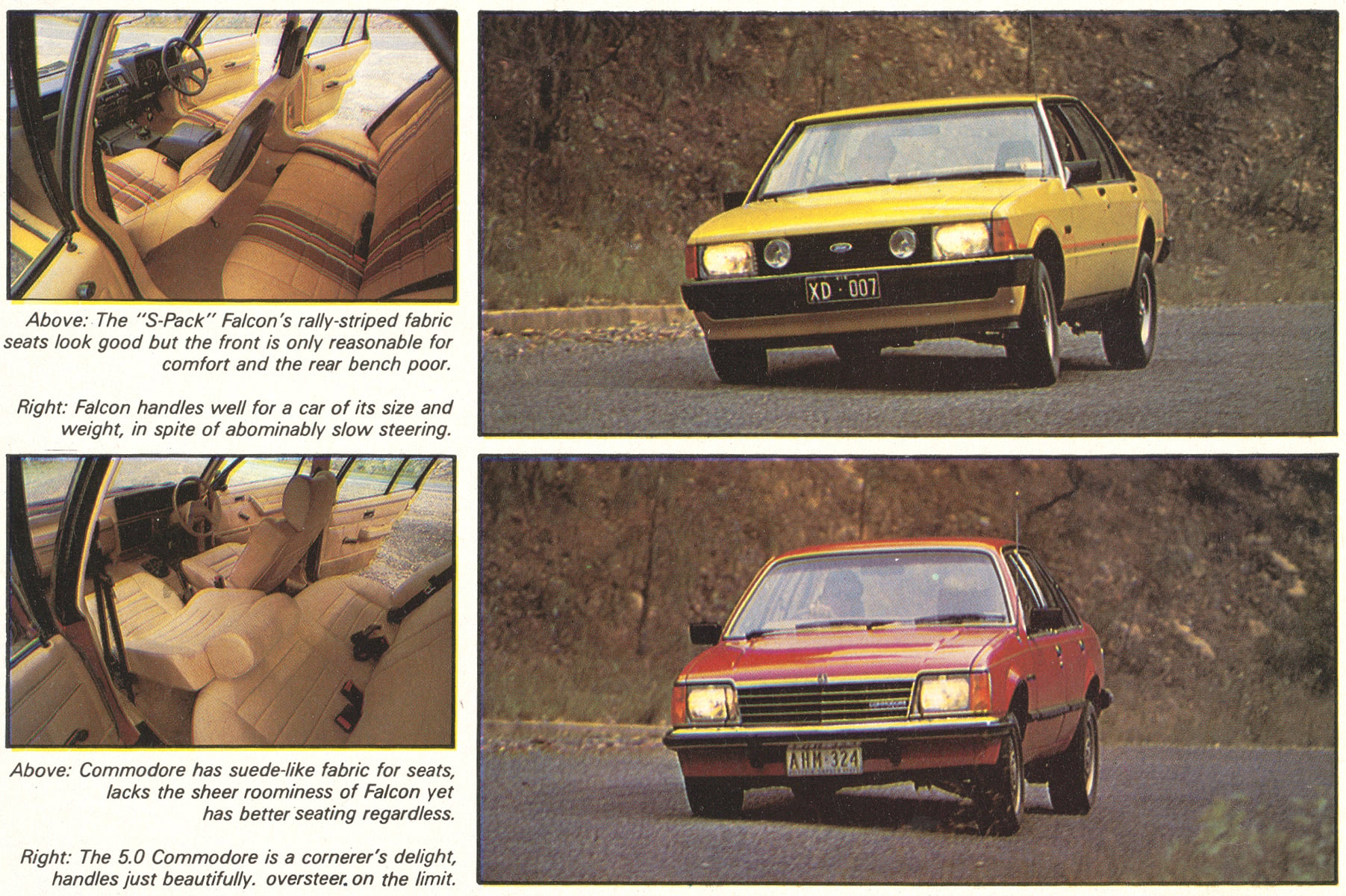

Though the Falcon holds a clear edge for performance on the straights, the Commodore reverses the decision through the twisty bits. It handles beautifully. Snaking through the slalom test the Commodore was seconds quicker than the Falcon, regardless of who was driving. It’s the same on the open road … in really demanding give and take conditions the Commodore has a clear margin over the Falcon, or does it noticeably easier when in convoy behind the Falcon.

To give the Falcon its due, it has to be the best handler ever in the traditional Australian family-car size class because it gets round corners and generally handles better than any Falcon, Holden or Valiant. But it’s just too big and heavy to compare directly with the smaller, lighter, more responsive and better balanced Commodore.

The Falcon is an understeerer, not seriously but habitually. It doesn’t do anything bad – doesn’t plough its front-end and scrub the bejasuz out of its tyres – but it lacks fine throttle responsiveness and some of our crew thought it hasn’t as much light-on-its-wheels, ultra-controllable feel to its handling as cleverly optioned XA/B/C Falcons.

It’s difficult to be too categorical about the Falcon’s handling because it loses a lot in the translation through the dud steering. It’s strange but true that in these days Ford can still manage to engineer (?) a steering system that needs five and a half turns lock to lock … and is h-e-a-v-y-with it. On top of which it still has a vast turning circle.

At times the Falcon’s steering is just too slow and slack for safety; as when trying to quickly turn tightly into a traffic lane and finding not only that your arms have to work like fury but that you also overshoot the centreline. The manual steering is the Falcon’s single most serious flaw. We believe the power-assisted steering ought to be a mandatory inclusion with the V8s (the 4.9 as well as the 5.8) instead of a $272 your-choice extra. The power steering has its problems, namely too much lightness and too little feel, but at least it almost halves the movements needed to turn the car.

The Commodore contrasts because its steering, by powered rack and pinion is one of the best available, regardless. It’s nicely direct and amply, but not excessively light.

The Commodore also wins the roadholding department for it is superbly sure-footed from its initial mild understeering attitude through neutrality to throttle-responsive oversteer at its very high limit of adhesion. The Falcon reaches its limit a bit lower down the scale and is less tidy in the process. Bumpy corners are taken in stride by the Commodore, its suspension soaking up the worst of the roughery and remaining virtually unaffected. In the same circumstances the Falcon reacts with a sharp side-stepping rear-end twitch before settling into its modified wider line.

Ride

Another plus for the Commodore here. The Falcon rides firmest of the two even on main routes and away from the highway its poise stiffens in direct relationship to the road condition, so you have to rely more on the seats than the suspension to absorb the harshness. It’s not uncomfortable, just not as comfortable as the Commodore which has suspension not necessarily softer but more supple.

Brakes

It’s a good win to the Falcon in the braking department, in spite of losing points for the handbrake which wouldn’t hold the car on a 1:4 grade and was accordingly voted unsatisfactory. The Commodore’s handbrake held firm.

The footbrakes were a different story however. The Falcon had a very good pedal with firm but progressively modulated feel and no lost travel. The brakes’ efficiency and stability in deliberately abusive conditions gave us every confidence them. The Commodore’s brakes worked well enough too, albeit not quite so impressively at the limit, but the pedal was (as we’ve noted on some other Commodores) disappointingly soggy with long travel to a spongy conclusion. The test car was a rather long toothed early build car, later models have a more progressive pedal.

Noise

For all its shimmering and shaking at standstill the Falcon proved to be the quieter of the two at idle, by a big margin. It was slightly noisier than the Commodore at steady 60 km/h and during maximum acceleration, but there was no difference between them for 100 km/h cruising. Both in fact are pleasantly quiet in normal conditions with little wind, road and other noises to disturb the relative calm. Indeed it was perhaps because of them being so un-noisy in other ways that the gearboxes’ growls seemed notably obvious.

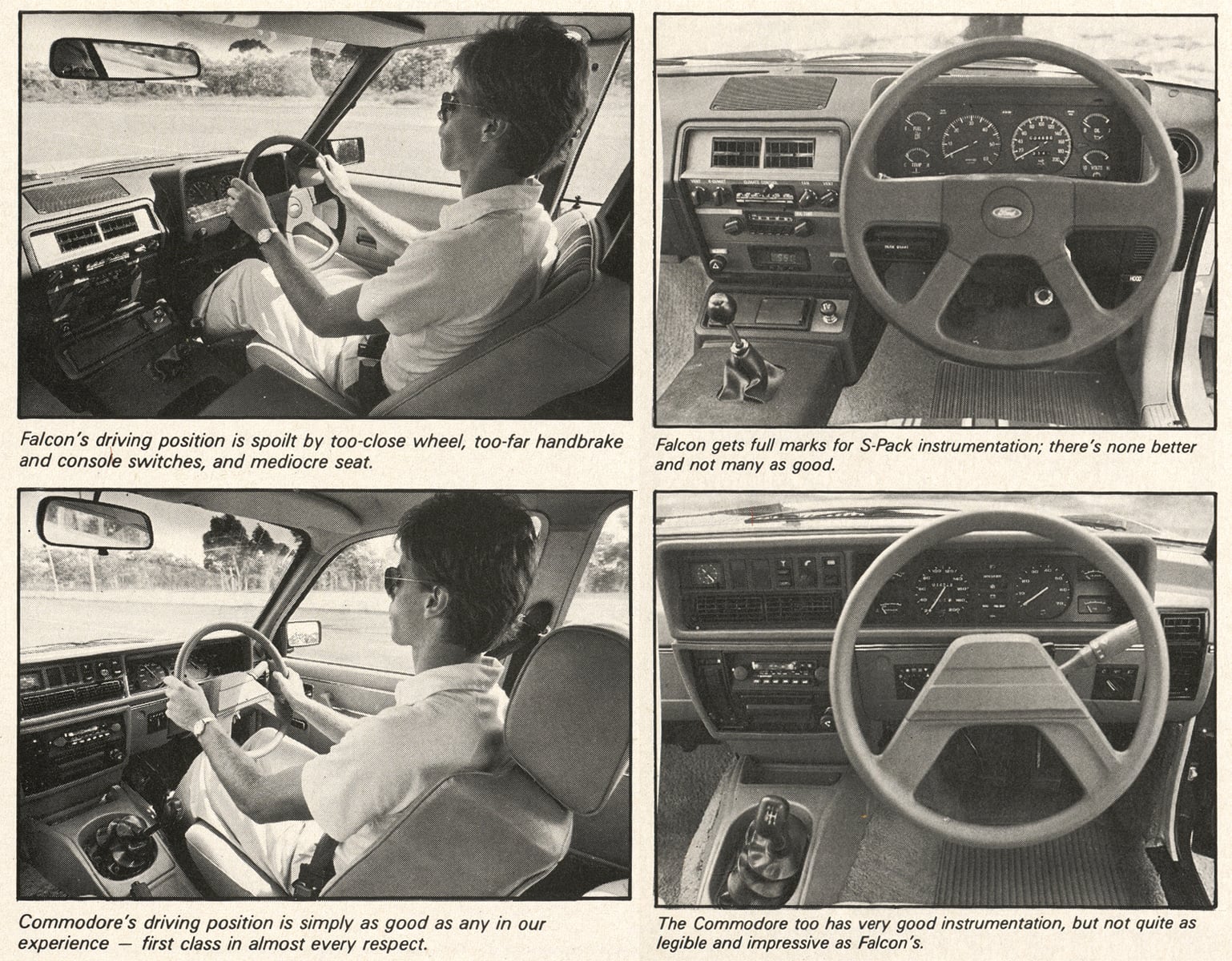

Interiors

The Commodore’s a clear winner here. Though it hasn’t as much room as the Falcon, the Commodore makes better use of what it has got. Nowhere is that more evident than at the rear seat (and boot). Aside from being much wider than the Commodore, the Falcon offers extraordinarily generous rear legroom. Even with the front seats right back, very tall (about two metres) rear-seaters have knee-room to spare.

They have less spare space in the Commodore but aren’t cramped there either. The difference is that the Falcon’s rear accommodation simply isn’t comfortable. The Ford’s cushion is about 50 mm shorter than the General’s, and softer with it, so the edge falls away and you’re effectively perched only on your coccyx (tail), and that’s not nice. The Commodore’s bench is wider and firmer and a much more comfortable place to be for any length of time.

The Commodore also wins at the front for its buckets give more support than the Falcon’s while offering the advantage of height adjustment and a wider choice of positions which (unlike the Falcon) enables tall drivers to put the wheel at arms’ length.

The Falcon’s “bigger” theme includes the instruments which are just that much larger than the Commodore’s. And it has to be said that while the General’s instrumentation is about as good as you’ll get for layout and legibility, Henry’s is even better – truly excellent.

Where the Falcon loses some of the ergonomic vote is in requiring a stretch to the centre console for the air/heat/fan/vent controls, the knobs of which are well identified in large letters but all with the same shape and not illuminated at night.

Luggage space

It seems a reasonable assumption that many V8 buyers shop in that market because they want a car for long hauls with a load of passengers and their luggage. That being the (suit) case, they may well find the Commodore the more practical of the two because it has a much more capacious boot than the Falcon where the shallow floor is a real limitation for bulky luggage.

The Verdict

If you consider them in relation to size (especially width), the Commodore and Falcon really aren’t directly comparable because the Ford is so much bigger. But if you look at the V8s purely as performance cars, then it may be a fairly close thing, depending on your priorities.

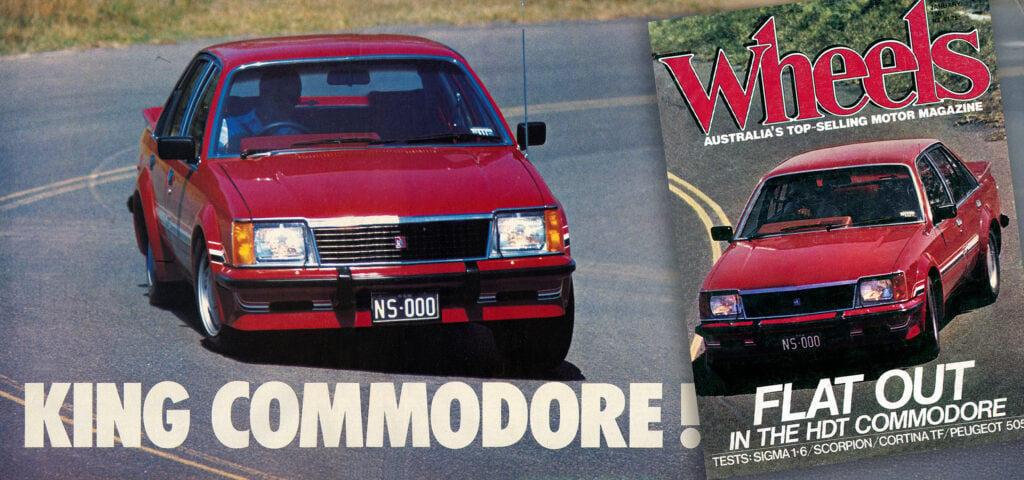

To some beholders the Ford is a beauty; to others the Commodore is more attractive. On paper the Falcon has the superior acceleration. But on the road, after swapping between the rivals time and again in different conditions, there’s no doubt about it … the Commodore is the drivers’ car and earns the right to the crown. King Commodore rules.

We recommend

-

Ford Falcon

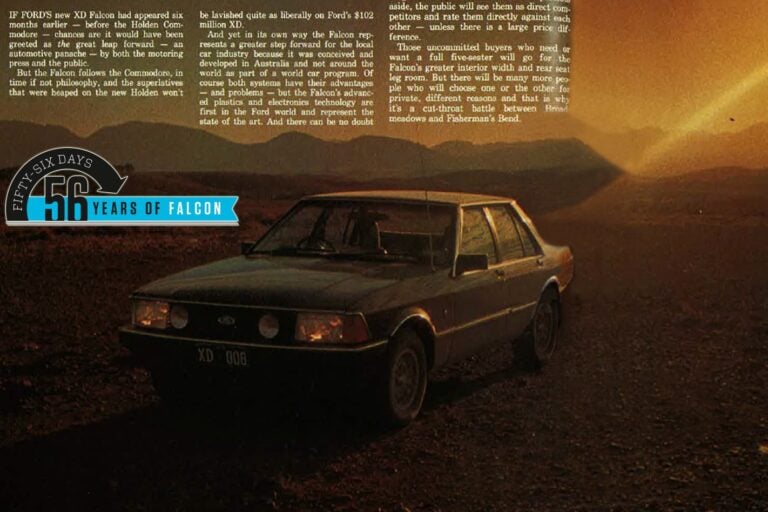

Ford Falcon1979 Ford Falcon XD: The new era dawns

We finally get our Aussie designed and developed Ford Falcon.

-

Classic Wheels

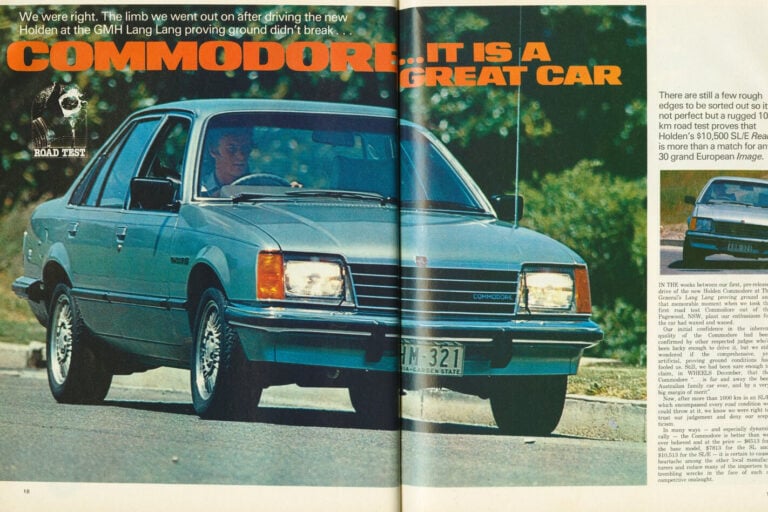

Classic WheelsRetro Review: 1978 Holden VB Commodore review

Our very first road test of the very first Commodore

-

Features

FeaturesTop 10 classic Australian muscle cars

Australia’s golden era of V8 thunder and Bathurst glory lives on with our definitive Top 10 classic muscle cars from 1967 to 1986 — legends, all.