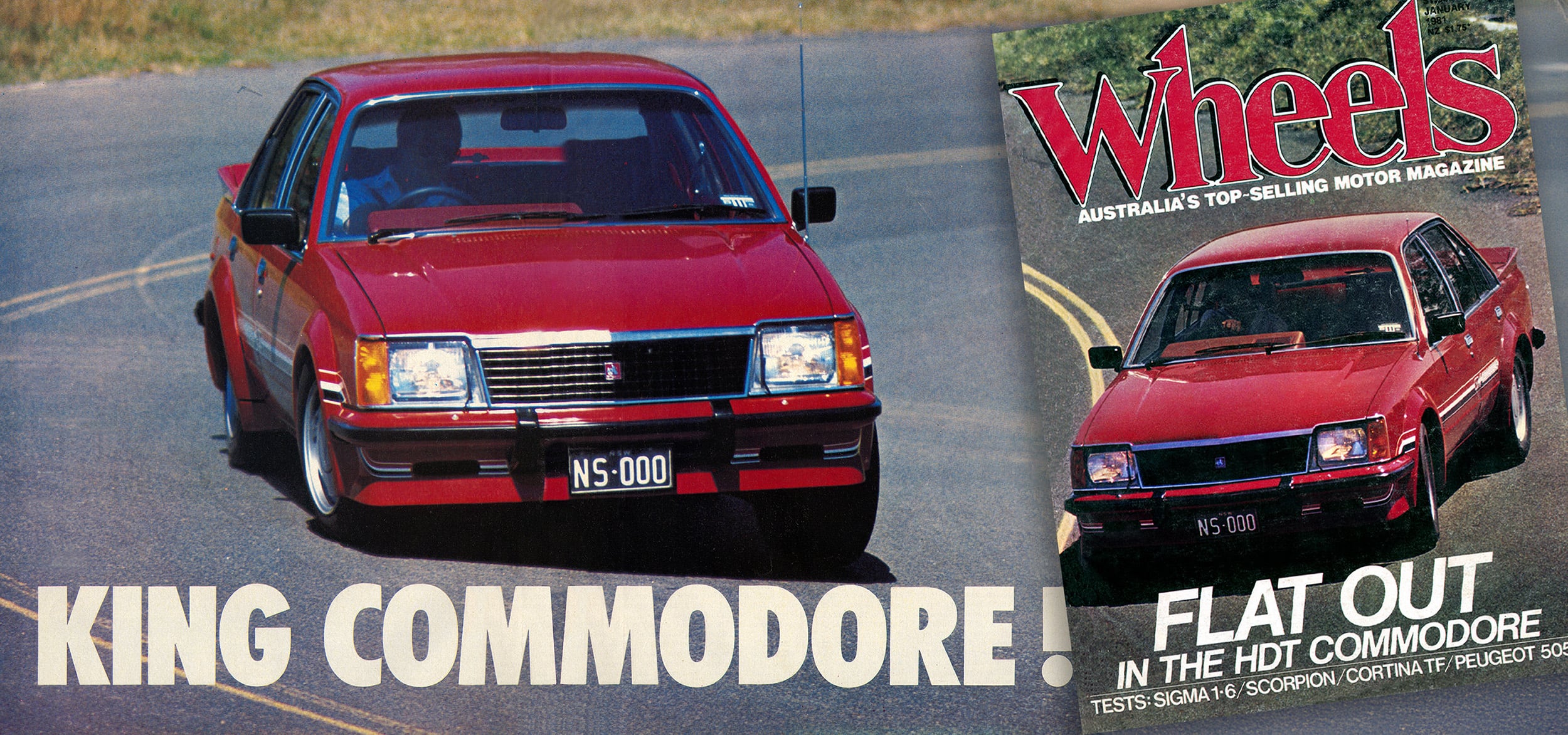

First published in the January 1981 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

First off, here’s the answer to the question everyone has been asking. The manual five-litre HDT (“Brock”) Commodore runs a standing 400 metres in 15.5 seconds and has a top speed of 208km/h. That’s a whisker under 130 mph. That’s one pub argument settled.

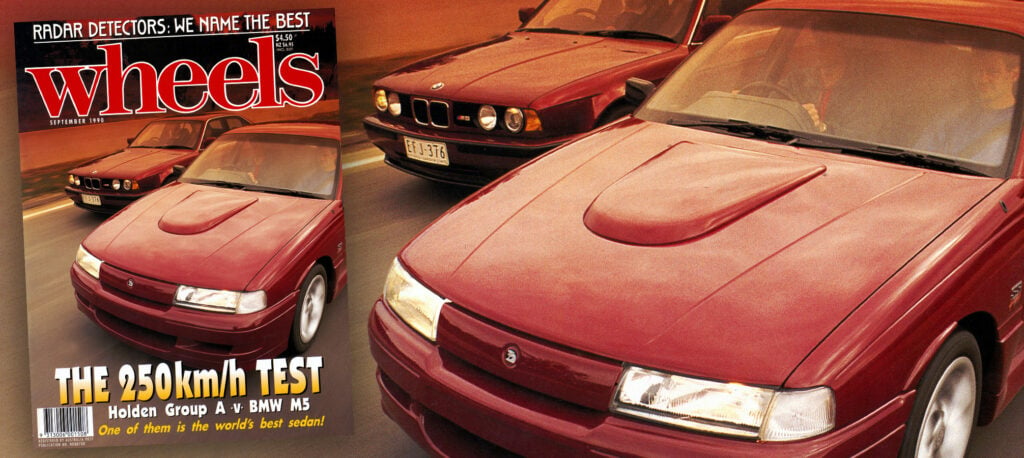

It is certainly today the fastest Australian-built road car, for the 5.8-litre Falcon in its best option form runs over the quarter in 15.8 seconds and won’t match it in top speed. The inevitable disclaimer follows: The car Wheels tested was still nursing its bruises from the 11-car Commodore race at the Calder AGP meeting, and the edge had certainly gone off the tune (it had certainly gone from the excellent brakes) and in absolute prime-time trim would certainly have run, at our guess, a 215km/h top speed.

Wheels November reported briefly on a press day drive with an automatic version of one of the 500 custom cars that Brock’s Special Vehicles Division is turning out for Australian motorists who still want all the grunt of a big V8 with first-class ride, handling, comfort and interior quiet – in other words, an Aussie super touring car that does everything a BMW or a Mercedes can do without the price tag, and can haul big boats up slimy launching ramps as well.

It has an automatic version that Editor Robinson drove (something like 70 per cent of the output will be autos, the last of the American Turbo-Hydramatics to be incorporated in a Commodore), but we have all been waiting for a crack at the manual.

The car we got was the black mother (our photographic car is a Firethorn Red example courtesy of Suttons Motors) that Brock drove in those two heats of the Calder clash, winning the second heat but losing overall to John Bowe on aggregate.

It still had the pushed-in driver’s door, a packet of Marlboro Brock had left in the glovebox, and front discs that had obviously glazed themselves to the point of no return, even with less than 600km total on the odometer.

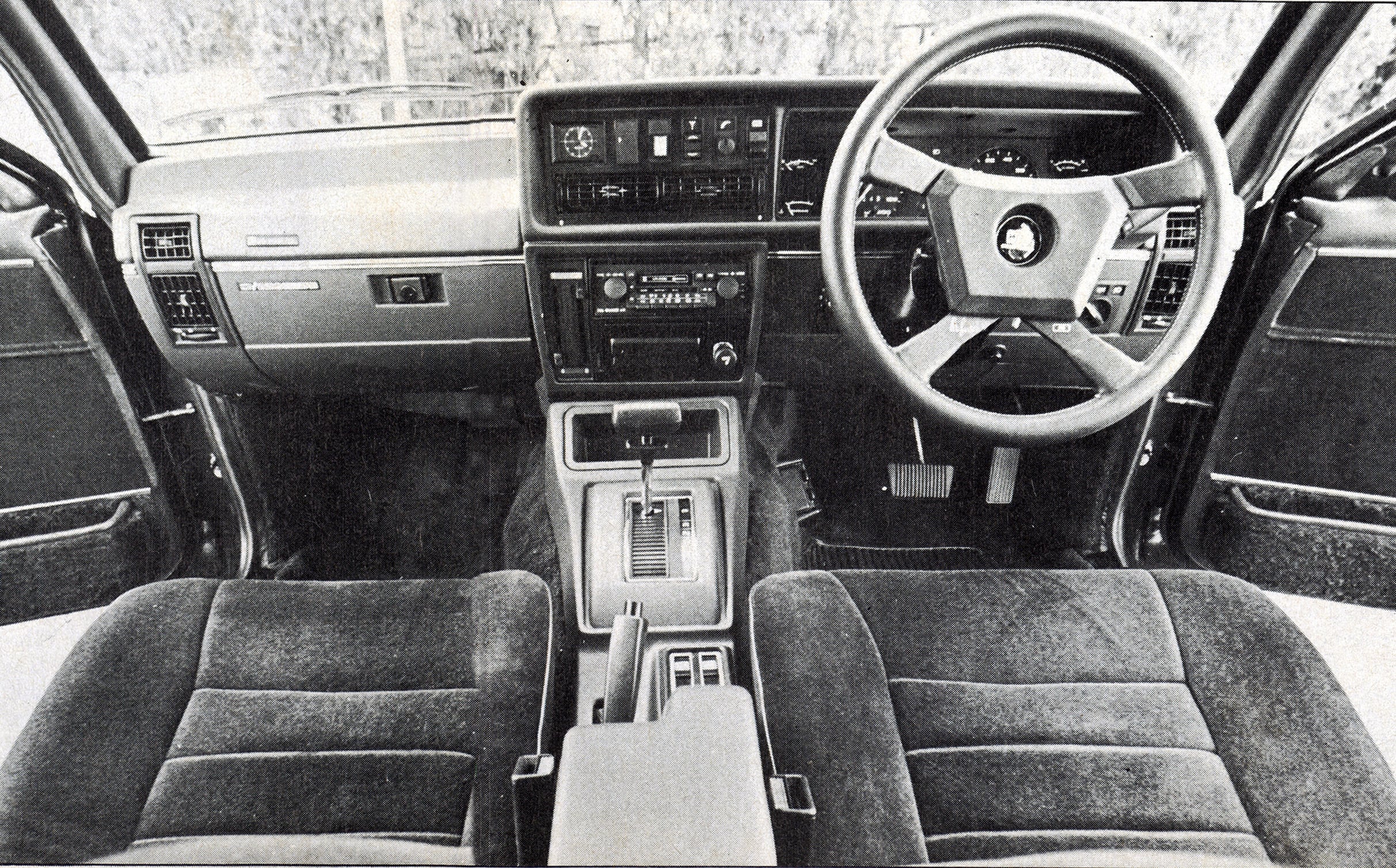

It was still in full racing livery, with “Brock” lettering and Big M decals and roll cage and fire extinguisher and full shoulder harness. The contrast of that with the total SL/E equipment of central locking, power windows, AM/FM stereo cassette player, aircon and velour trim put us in the position of the unwilling chauffeur out for the day in his boss’ hoon car.

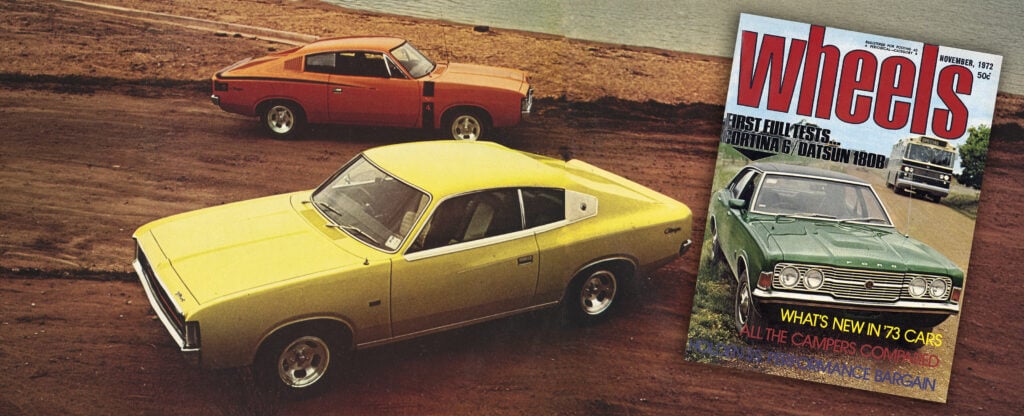

The comparison between the HDT Commodore and the 1967-to-1972 “super cars” – the Holden Monaros and the GTHO Falcons – is irresistible to anyone who has driven both. First of all, they are roughly about as quick overall, although a memorable Wheels test put the Phase III HO top speed at 144 mph, which at 231km/h made it the fastest road car ever built in Australia.

The difference is that the Brock Commodore is not only much more refined, smoother, quieter and more docile, but it is in today’s terms a baby limo. The sixties super cars were rough, lumpy on idle, coarse in the gearbox, and heavy in the steering. The only difference between this Commodore and the standard full option SL/E is in the way it reacts when you bury the foot and the subtle, compliant expression of control from the Bilstein gas shocks.

Let’s recap on the specification of the car. Delivered to the Brock Special Vehicles operation in North Melbourne is a five-litre SL/E (no more are being built after the end of January) Commodore, with standard specs of aircon, power steering, velour trim, factory alloy 60 profile wheels, four-wheel disc brakes, automatic power antenna, AM/FM stereo radio cassette, laminated screen with tinted glass all round, heated rear window, remote boot release, rear compartment lights, front map lights, headlamp wash/wipe system, dual rear vision mirrors, dwell wipers, and height-adjustable driver’s seat.

Added to that is the so-called “333” pack, which includes dual exhausts, central locking, electric windows, and a few other small items. The fact that you can’t order the 333 pack with manual transmission (in fact, you probably can’t order a five-litre engine since last September or so) is incidental.

So then Brock’s team, headed-up by Bathurst team driver John Harvey – who defected to the Brock organisation from his job as trouble-shooter for the Ensign tyre retail chain in Victoria – descends on the car to make a multitude of changes.

The body gets a plastic air dam, rear deck spoiler and wheel arches. Side and rear striping (designed, we hear, by GMH’s Leo Pruneau) complement the three arbitrary colors – red, white, and black, coincidentally the colors of the Marlboro Holden Dealer Team. A rear fender badge commemorates the Brock racing Commodore win in the 1980 Australian Touring Car Championships.

To our mind the exterior effect is a bit boy-racer, if you’ll pardon the expression. The problem that confronts some would-be buyers of $19,000 worth of what is certainly one of the great touring cars of the world is that the exterior treatment tends to ask for a boot in the door or a key scraped along the side.

Inside, the cosmetics include a (smaller) four-spoke Momo steering wheel in black leather, numbered and signed by Brock, and a fake-wood gearshift knob. A small and very useful rest for the left foot is installed. All else inside is stock SL/E.

So much for the cosmetics. They are helped by Irmscher Tuning (German) alloy road wheels, with a wheel offset identical to the Australian Commodore, and an inch wider. The tyres are Uniroyal ER60-15s, and Brock, through his association with Uniroyal, had a real hand in their development.

Brock’s understanding of suspension design is, frankly, remarkable. We suspect that GMH’s engineers may have been consulted at some stage during the process of testing and developing the prototype car, but that takes nothing away from the sincere yet subtle changes that have been made. Brock says he started with a good-riding, good-handling car, and mainly wanted to improve high-speed touring control, particularly in crosswinds and over indifferent bitumen surfaces.

He put a lot of work in with the Bilstein distributors in Melbourne (who also worked with Ford on the ESP package) and re-worked spring rates, roll centres, front camber and castor, and front and rear stabiliser bars to improve straight line stability and reduce bump steer. The main consideration was to maintain a good ride, and this they have certainly done. For want of a better word, the car isn’t “clunky” over minor irregularities in the road; yet it will soak up ripples and bumps in corners without shaking its head.

A larger-capacity brake master cylinder goes in-a lesson, Brock says, from using it on the Repco Commodores. They also refill with Castro! GT (LMA) brake fluid. That does not go very far to explaining why the system produces a pedal with that marvellous progressive feel, through which (as this magazine has been saying for years is the measure) you can dial in exactly the retardation you want with your big toe, and get the exact result.

Engine: Obviously, this was Brock’s biggest problem. Five litres of relatively elderly American-cum-Australian V8 despite the improvements made to the current XT-5 series-does not exactly offer promise of the kind of fuel consumption your Mercedes or BMW driver would anticipate.

GMH – whom, we must stress, has made little contribution to the development of the car except for advice and consultation – agreed to run an early prototype through its emissions testing system at Lang Lang to ensure the car would pass the Australian Design Rules requirements. If you see that, as we do, as a courtesy to a man who has contributed so much to the reputation of GMH products, then we feel your viewpoint is correct.

Anyway, the engine passed with flying colours, and with quoted (not AS2077) figures of an overall average 9.3 km/I (26.1 mpg). We couldn’t verify this in our testing, because Melbourne’s amazing weather varied from heatwave to freezing downpour during our brief testing, and we were more concerned with getting those two important performance figures.

Nevertheless, Brock says loudly that the average driver will get up to 20 per cent better fuel consumption than the standard five-litre. We beg to question whether the man who could afford a Brock Commodore would care a damn about that, but we have agreed with Brock the right to disagree with him…

What was done to the engine really was to apply some basic tuning principles that have been used by performance engine builders since the early sixties. However, what is really interesting is that none of the work is hand-tool stuff; it is all done on automatic machines, which suggests that some of the ideas are capable of being reproduced in five-litre V8s inserted into future Statesman builds.

The cylinder heads have been machined for better gas flow; larger inlet and exhaust valves are fitted, and valve seats and porting have also been machined. In common terms, it’s a good “head job”, if you’ll pardon the expression.

The inlet manifold is smoothed out as well; all this produces a lower compression of 8.9:1, allowing better NOx control and a little more ignition advance, and thus better part-throttle economy. A bigger (Chevrolet) air cleaner and a cold air box-racing experience again allow lower combustion chamber temperatures, and thus more efficient spark plugs to be used. Add a bigger fuel line to deliver petrol better, and a few other “tricky things” that Brock doesn’t talk about too freely, and you have an engine that idles at 600rpm in all conditions, spins like a top, and is super-smooth all through the range. Our guess is that a lot of racing experience has gone into the total car, particularly in engine, brakes and suspension.

Cold facts can’t convey all this. You do, in fact, get into this car, and say to yourself immediately that it works precisely as a great touring car should. This immediate impression wasn’t spoiled even by the caning the brand-new car had had over about 30 hard laps of Calder. The front brakes were stuffed, the rear discs squealed when you used the handbrake to stop (as we were doing in low-speed city traffic) and you still had to clear its throat by blipping the throttle in parking or traffic turns.

All that went away when you found a clear piece of road and depressed the foot, winding the big V8 out to 5800rpm, where it started to break down. The most impressive thing was the gearshift; current GMH Commodore manual shifts are not renowned for the knife-through-butter description, and we don’t know whether the shorter lever (as it felt) or the new fake-wood knob (ridiculous assumption) were responsible. All we can say is that the gearshift was marvellous.

Everything has come together in this car. Knowing that behind you is the heavy-duty 3.36 limited-slip differential, you could mash on the power and the thing would just steam away, up to 5800 in every gear like a turbine, back on to the brakes and back down on the shift, turn the wheel a quarter into the corner and bang down the grunt pedal and on it would go.

In the wet (as it mostly was) one quickly learned that the system didn’t change, because in adding the power on the exit you simply felt the suspension talk back a little louder and applied the required correction without lifting the foot.

For want of a better word, it was just… nice. It is a car that will never, ever, play a trick on you. That difficult achievement of imparting total driver confidence is carried to the ultimate in this car in a way that you seldom experience. It constantly reminds you of its racetrack breeding, but not in the harsh way that that phrase normally implies.

The standing quarter runs were almost monotonous. Load it up to around 3000 (or 3200 or 3600 – it didn’t really seem to make much difference) and the black kid would squeak a bit at the back, and squirm slightly, and then the bite would come in and you would then simply watch the tacho so you could pluck another gear at 5700 to beat the valve bounce (it wasn’t valve bounce really, more like a hydraulic lifter flutter) and then on again. There was no wind, and the quarter times varied by only 0.2 secs either way.

On the top speed runs, the end seemed to come not through valve bounce or breathing but through the lack of that last little edge of crispness. Over the years you get used to American V8s running out of puff in the top end (although we remember clearly that the 350-inch V8 used in the Monaro of 1969 was limited mainly by driver courage). But the black car just went a little flat; the last 20km/h took a long time coming up. We suspect the timing had slipped a little.

So where does all this leave us? Simply, that this HDT Commodore has no peer in Australia as a touring car for the kind of usage that a small percentage of Australians demand. It is very probably bullet-proof; it will certainly tow anything that the caravan or boat brigade care to hook on behind it; it will do an interstate trip as easily, with as little drama, and in as much comfort as a European car costing twice as much.

This is probably because it has now above and beyond the normal flagship Commodore, acquired the kind of keen edge that only a car modified by a racebred man can possibly have.

Our guess is that we have not seen the last of special vehicles from Brock. There will be in this country a solid, continuing, tiny market for this kind of car, that the enthusiast can recognise and love as something far removed from the correct, sensible and ecologically-proper mass produced vehicles that are with us now.

It is not as stupid as the surviving American customised convertibles and super long-wheelbase aberrations that have survived; it is not as deviate as the English limited-editions like the Panther. It probably says: Hey, here is a pretty good car that with the commonsense application of some years of experience in pointing vehicles along a piece of bitumen we can make into a fairly pleasurable piece of machinery that really owes no apologies to anything else built in the world.

And, accepting all that, accepting all the anti-social nature of what the HDT Commodore represents, you must say to yourself that this car is a repository of many of the things that made Wheels magazine what it is today. Isn’t that nice?

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesHolden VH Group 3 vs Peter Brock’s VH 05

Peter Brock's best road and race car head-to-head

-

Features

FeaturesTop 10 performance Holden Commodores

From VB to VFII, we gather the hottest-ever Holden Commodores - according to us

-

Features

FeaturesPeter Brock’s Bathurst-winning VH Commodore SS to fetch big money

The Lloyds Online auction has the car over $1.6m with two days left