First published in the September 1990 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

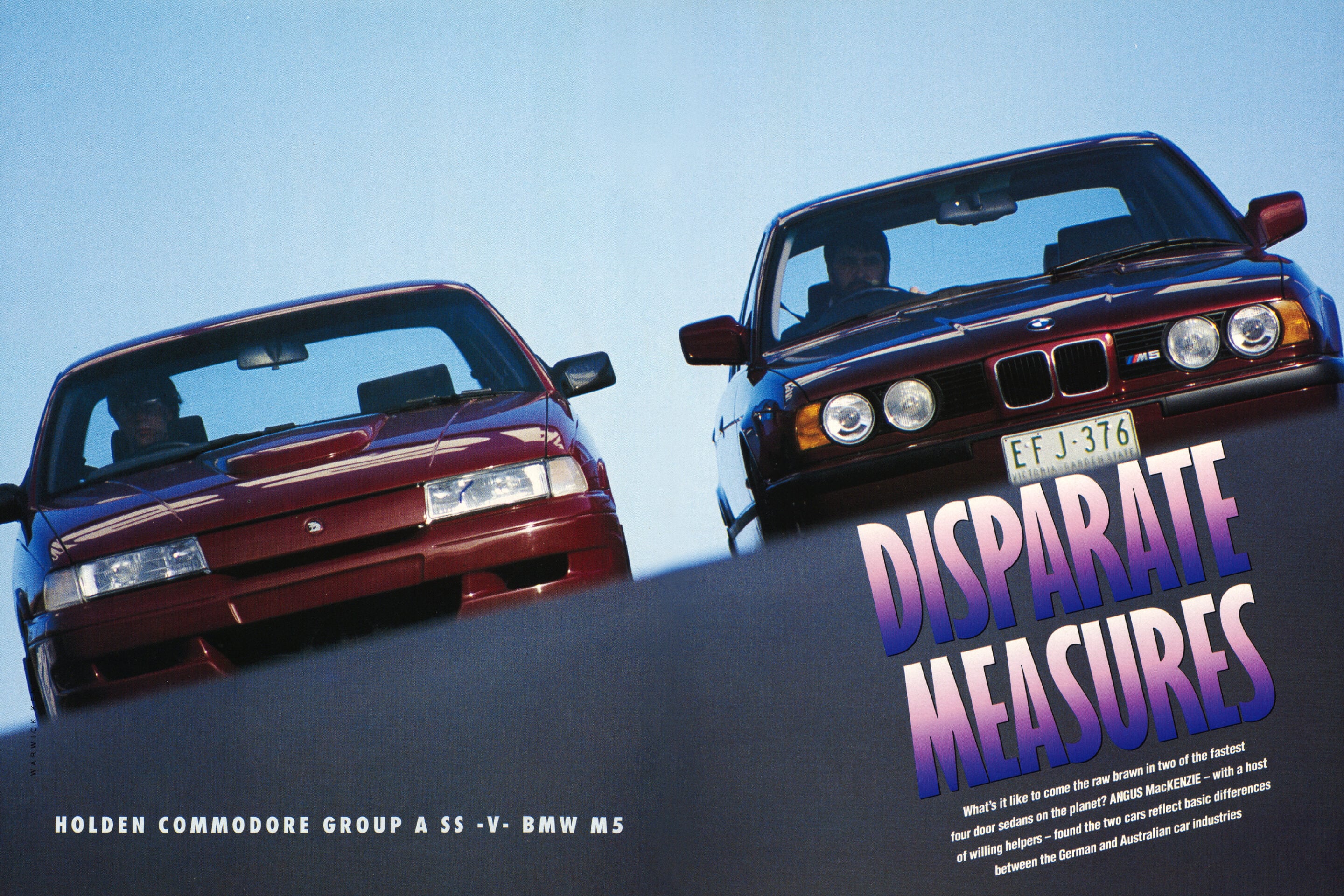

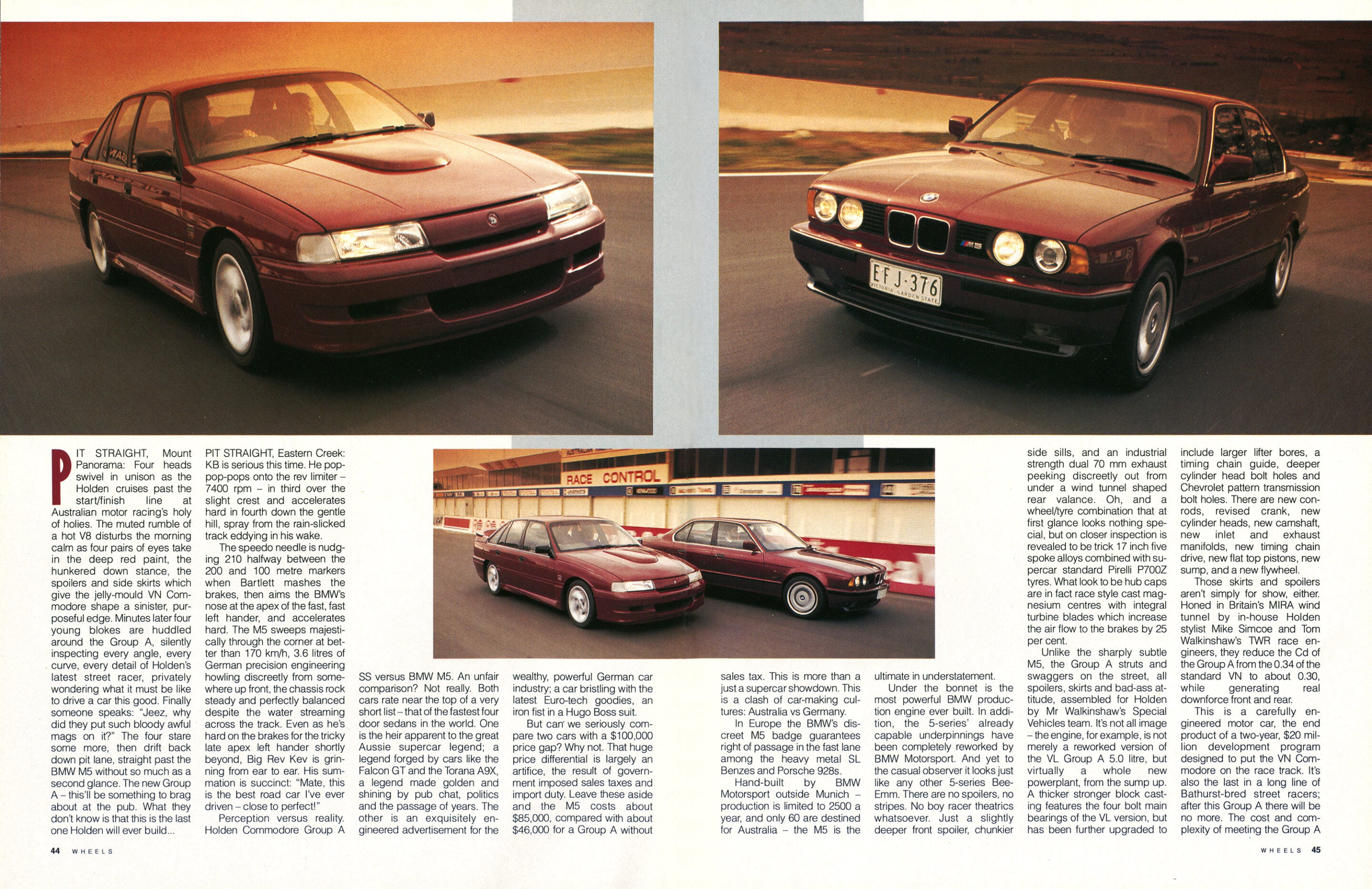

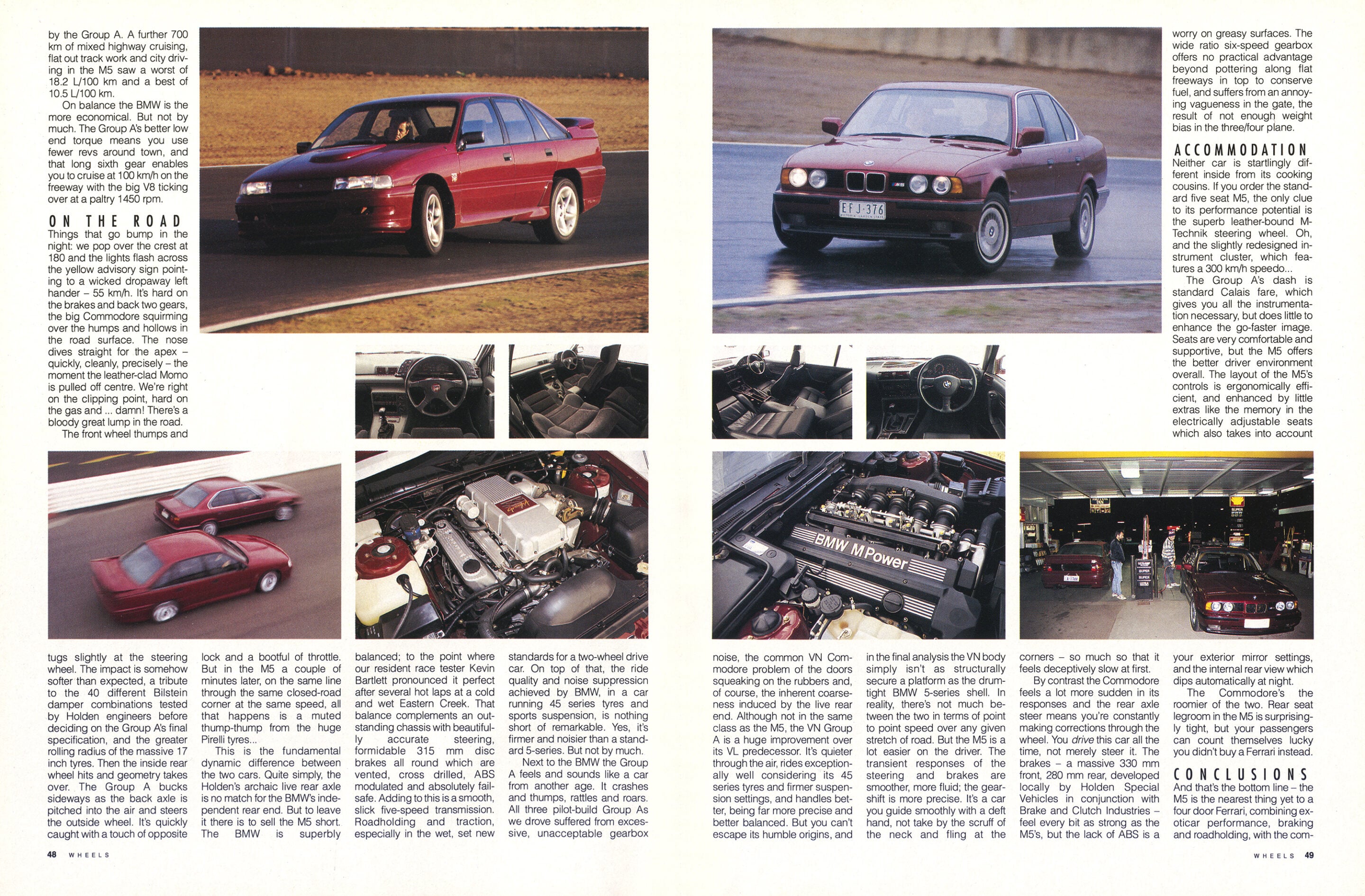

Pit Straight, Mount Panorama: Four heads swivel in unison as the Holden cruises past the start/finish line at Australian motor racing’s holy of holies. The muted rumble of a hot V8 disturbs the morning calm as four pairs of eyes take in the deep red paint, the hunkered down stance, the spoilers and side skirts which give the jelly-mould VN Commodore shape a sinister, purposeful edge.

Minutes later four young blokes are huddled around the Group A, silently inspecting every angle, every curve, every detail of Holden’s latest street racer, privately wondering what it must be like to drive a car this good. Finally someone speaks: “Jeez, why did they put such bloody awful mags on it?”

The four stare some more, then drift back down pit lane, straight past the BMW M5 without so much as a second glance. The new Group A – this’ll be something to brag about at the pub. What they don’t know is that this is the last one Holden will ever build…

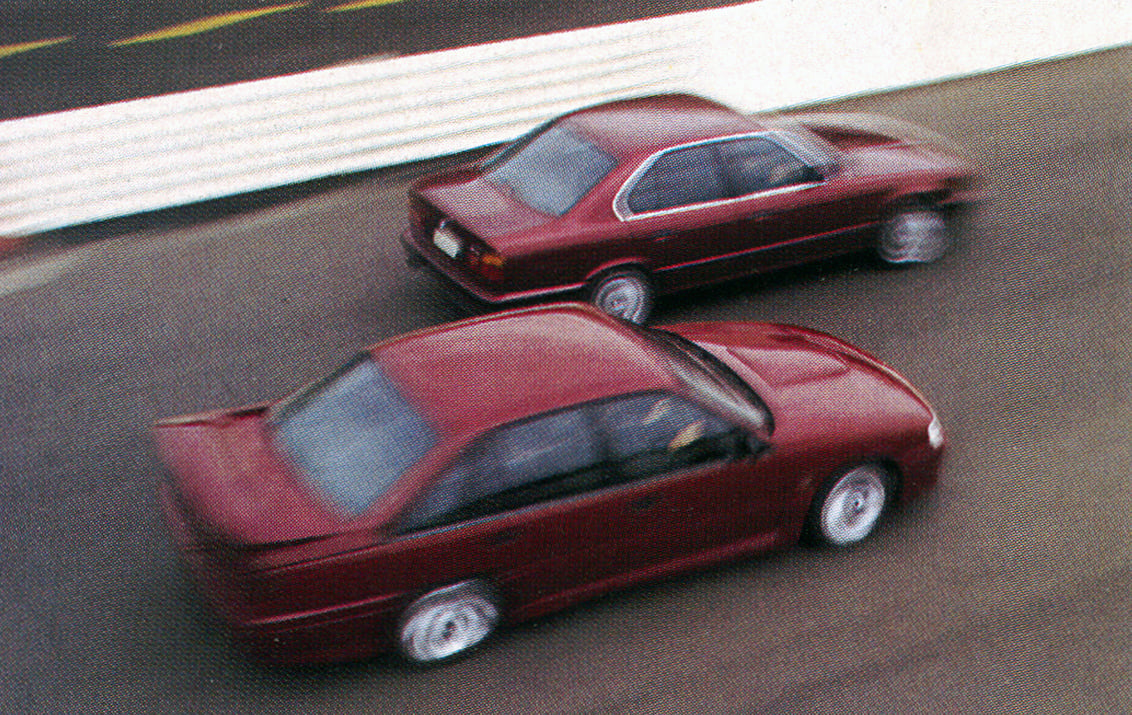

Pit Straight, Eastern Creek: KB is serious this time. He pop-pop-pops onto the rev limiter – 7400 rpm – in third over the slight crest and accelerates hard in fourth down the gentle hill, spray from the rain-slicked track eddying in his wake.

The speedo needle is nudging 210 halfway between the 200 and 100 metre markers when Bartlett mashes the brakes, then aims the BMW‘s nose at the apex of the fast, fast left hander. and accelerates hard. The M5 sweeps majestically through the corner at better than 170km/h, 3.6 litres of German precision engineering howling discreetly from somewhere up front, the chassis rock steady and perfectly balanced despite the water streaming across the track. Even as he’s hard on the brakes for the tricky late apex left hander shortly beyond, Big Rev Kev is grinning from ear to ear. His summation is succinct: “Mate, this is the best road car l’ve ever driven – close to perfect!”

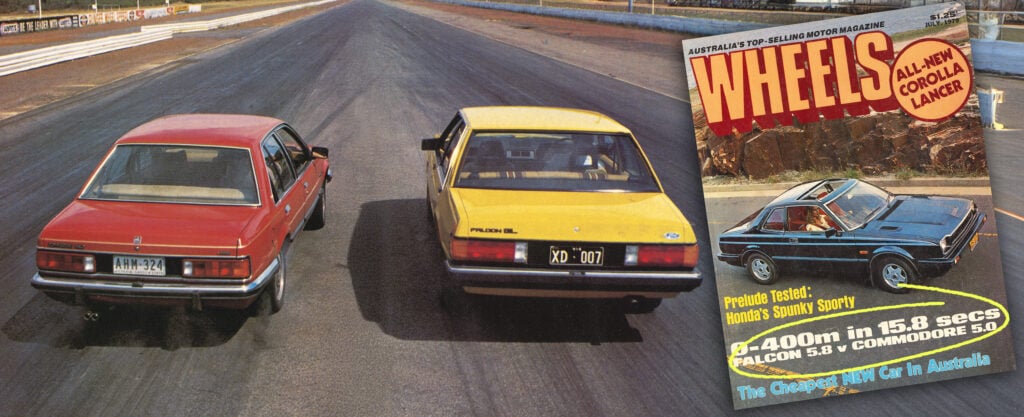

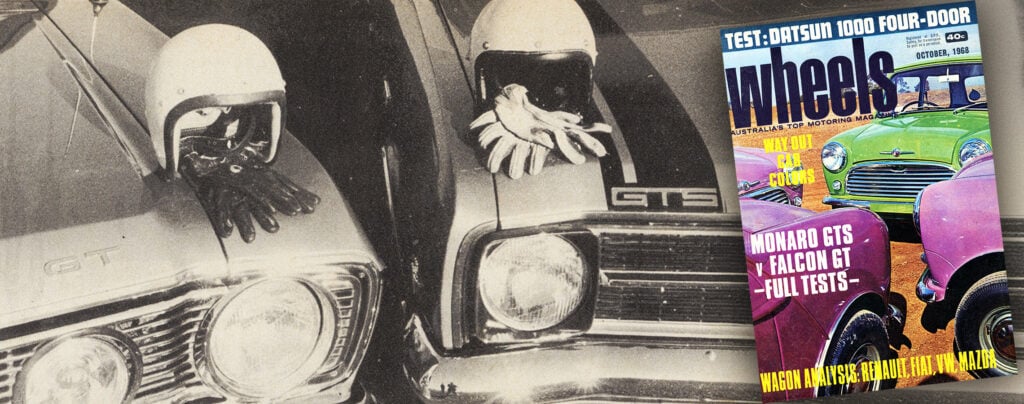

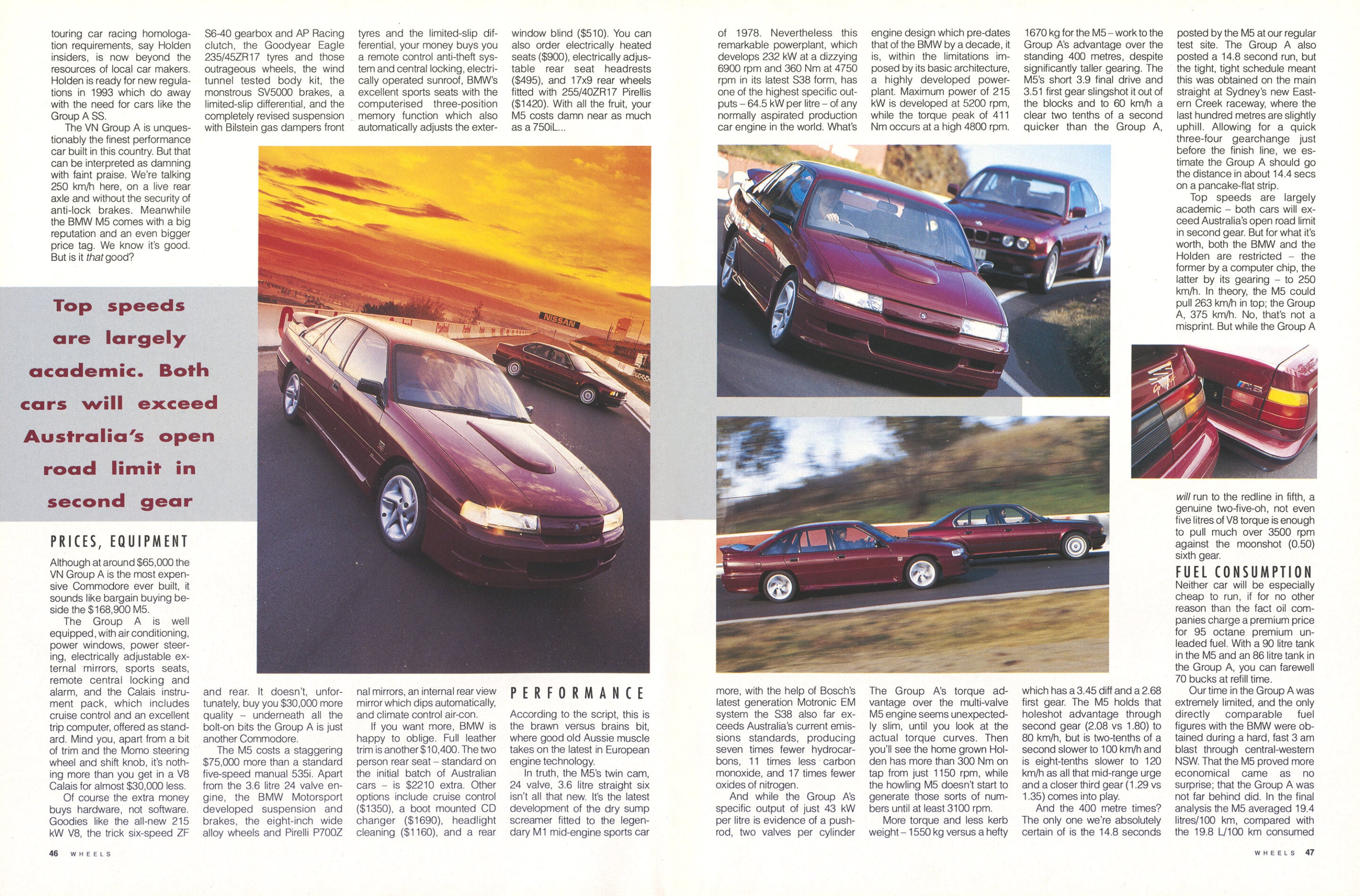

Perception versus reality. Holden Commodore Group A SS versus BMW M5. An unfair comparison? Not really. Both cars rate very near the top of a very short list – that of the fastest four door sedans in the world. One is the heir apparent to the great Aussie supercar legend; a legend forged by cars like the Falcon GT and the Torana A9X, a legend made golden and shining by pub chat, politics and the passage of years. The other is an exquisitely engineered advertisement for the wealthy, powerful German car industry; a car bristling with the latest Euro-tech goodies, an iron fist in a Hugo Boss suit.

But can we seriously compare two cars with a $100,000 price gap? Why not. That huge price differential is largely an artifice, the result of government imposed sales taxes and import duty. Leave these aside and the M5 costs about $85,000, compared with about $46,000 for a Group A without sales tax. This is more than a just a supercar showdown. This is a clash of car-making cultures: Australia vs Germany.

In Europe the BMW’s discreet M5 badge guarantees right of passage in the fast lane among the heavy metal SL Benzes and Porsche 928s. Hand-built by BMW Motorsport outside Munich – production is limited to 2500 a year, and only 60 are destined for Australia – the M5 is the ultimate in understatement.

Under the bonnet is the most powerful BMW production engine ever built. In addition, the 5-series’ already capable underpinnings have been completely reworked by BMW Motorsport. And yet to the casual observer it looks just like any other 5-series Bee-Emm. There are no spoilers, no stripes. No boy racer theatrics whatsoever. Just a slightly deeper front spoiler, chunkier side sills, and an industrial strength dual 70mm exhaust peeking discreetly out from under a wind tunnel shaped rear valance.

Oh, and a wheel/tyre combination that at first glance looks nothing special, but on closer inspection is revealed to be trick 17 inch five spoke alloys combined with supercar standard Pirelli P700Z tyres. What look to be hub caps are in fact race style cast magnesium centres with integral turbine blades which increase the air flow to the brakes by 25 per cent.

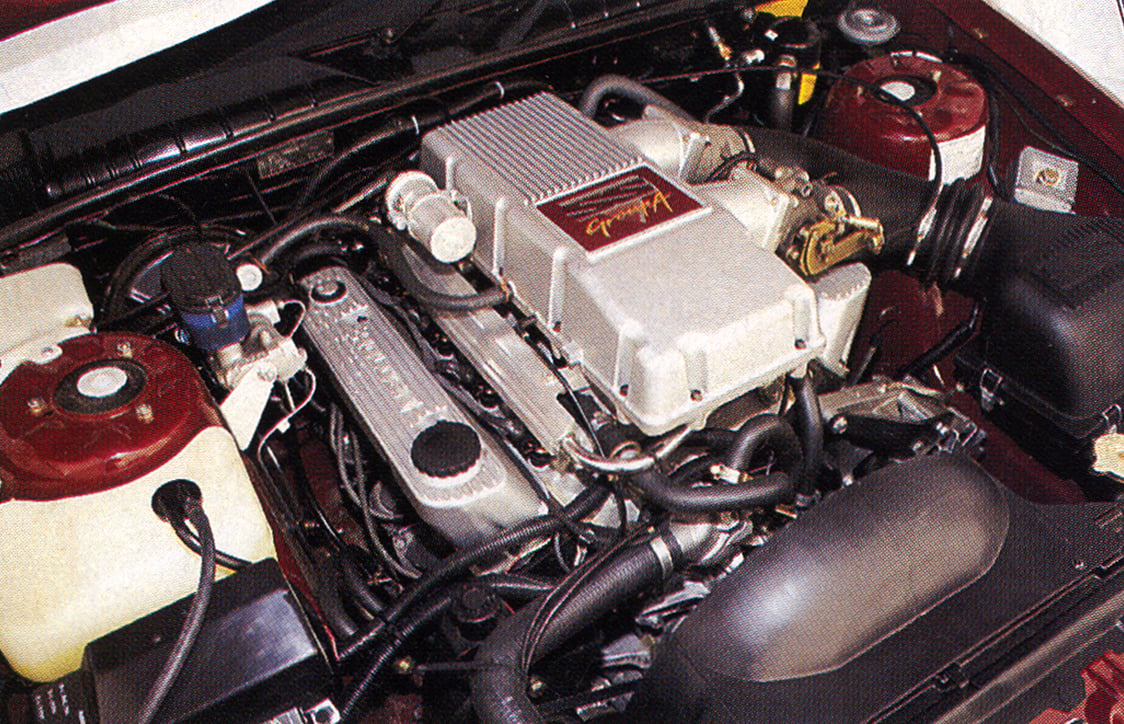

Unlike the sharply subtle M5, the Group A struts and swaggers on the styreet, all spoilers, skirts and bad-ass attitude, assembled for Holden by Mr Walkinshaw’s Special Vehicles team. It’s not all image – the engine, for example, is not merely a reworked version of the VL Group A 5.0 litre, but virtually a whole new powerplant, from the sump up. A thicker stronger block casting features the four bolt main bearings of the VL version, but has been further upgraded to include larger lifter bores, timing chain guide, deeper cylinder head bolt holes and Chevrolet pattern transmission bolt holes. There are new con-rods, revised crank, new cylinder heads, new camshaft, new inlet and exhaust manifolds, new timing chain drive, new flat top pistons, new sump, and a new flywheel.

Those skirts and spoilers aren’t simply for show, either. Honed in Britain’s MIRA wind tunnel by in-house Holden stylist Mike Simcoe and Tom Walkinshaw’s TWR race engineers, they reduce the Cd of the Group A from the 0.34 of the standard VN to about 0.30 while generating real downforce front and rear. This is a carefully engineered motor car, the end product of a two-year, $20 million development program designed to put the VN Commodore on the race track. It’s also the last in a long line of Bathurst-bred street racers; after this Group A there will be no more.

The cost and complexity of meeting the Group A touring car racing homologation requirements, say Holden insiders, is now beyond the resources of local car makers. Holden is ready for new regulations in 1993 which do away with the need for cars like the Group A SS.

The VN Group A is unquestionably the finest performance car built in this country. But that can be interpreted as damning with faint praise. We’re talking 250km/h here, on a live rear axle and without the security of anti-lock brakes.

Meanwhile the BMW M5 comes with a big reputation and an even bigger price tag. We know it’s good. But is it that good?

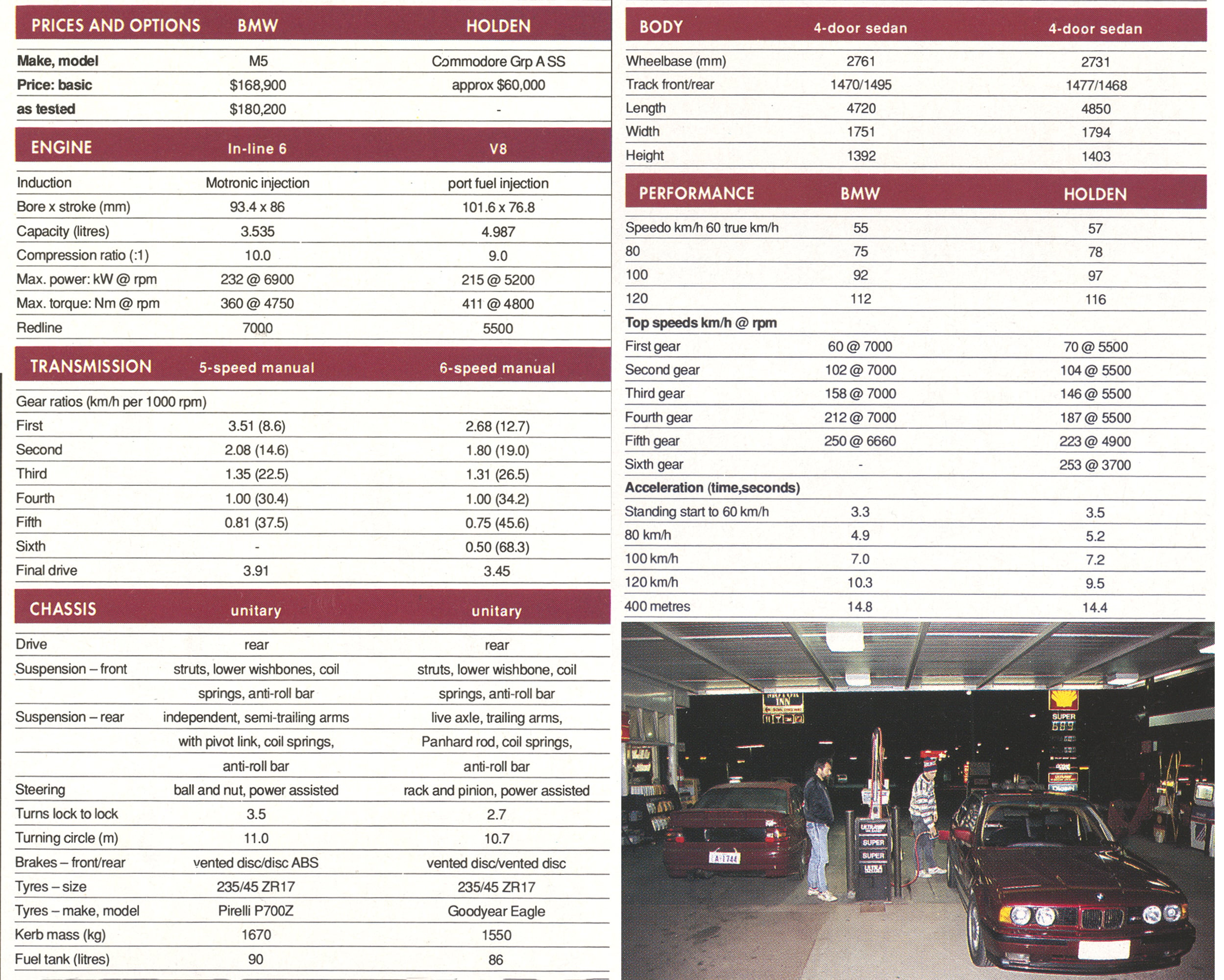

Pricing and Equipment

Although at around $65,000 the VN Group A is the most expensive Commodore ever built, it sounds like bargain buying beside the $ 168,900 M5.

The Group A is well equipped, with air conditioning, power windows. power steering, electrically adjustable external mirrors, sports seats, remote central locking and alarm, and the Calais instrument pack, which includes cruise control and an excellent trip computer, offered as standard. Mind you, apart from a bit of trim and the Momo steering wheel and shift knob, it’s nothing more than you get in a V8 Calais for almost $30,000 less.

Of course the extra money buys hardware, not software. Goodies like the all-new 215kW V8, the trick six-speed ZF S6-40 gearbox and AP Racing clutch, the Goodyear Eagle 235/45ZR17 tyres and those outrageous wheels, the wind tunnel tested body kit, the monstrous SV5000 brakes, a limited-slip differential, and the completely revised suspension with Bilstein gas dampers front and rear. It doesn’t, unfortunately, buy you $30,000 more quality – underneath all the bolt-on bits the Group A is just another Commodore.

The M5 costs a staggering $75,000 more than a standard five-speed manual 535i. Apart from the 3.6 litre 24 valve engine, the BMW Motorsport developed suspension and brakes, the eight-inch wide alloy wheels and Pirelli P700Z tyres and the limited-slip differential, your money buys you a remote control anti-theft system and central locking, electrically operated sunroof. BMW’s excellent sports seats with the computerised three-position memory function which also automatically adjusts the external mirrors, an internal rear view mirror which dips automatically, and climate control air-con.

If you want more, BMW is happy to oblige. Full leather trim is another $10,400. The two person rear seat – standard on the initial batch of Australian cars – is $2210 extra. Other options include cruise control ($1350), a boot mounted CD changer ($1690), headlight cleaning ($1160), and a rear window blind ($510). You can also order electrically heated seats ($900), electrically adjustable rear seat headrests ($495), and 17×9 rear wheels fitted with 255/40ZR17 Pirellis ($1420). With all the fruit, your M5 costs damn near as much as a 750iL…

Performance

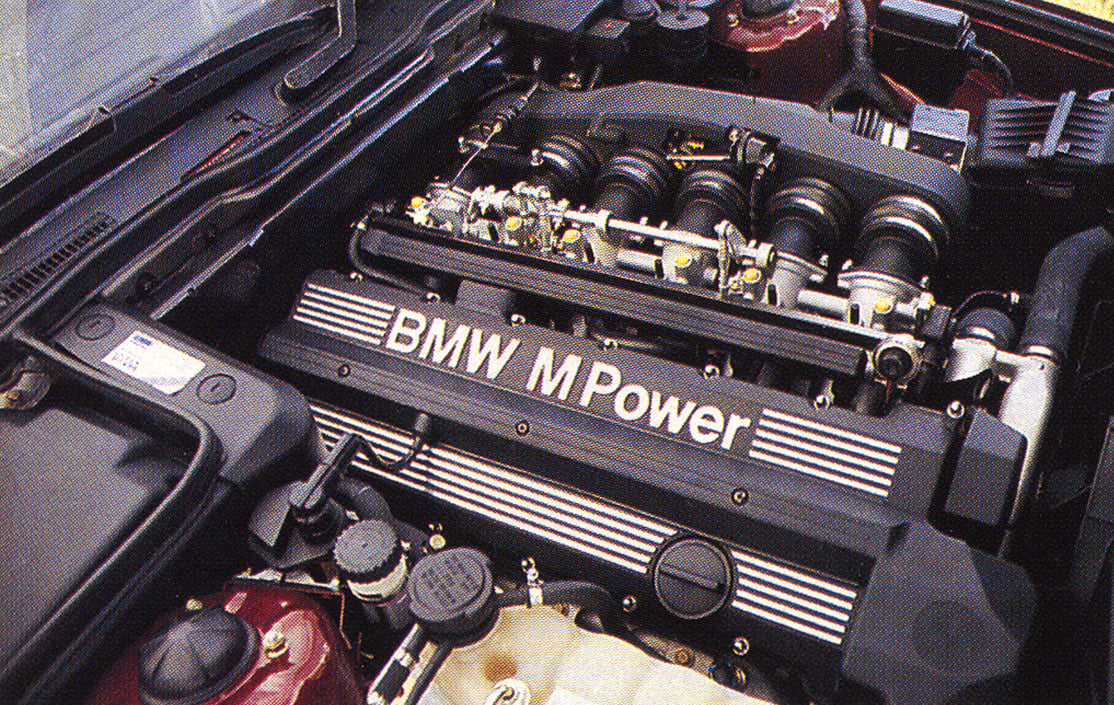

According to the script, this is the brawn versus brains bit, where good old Aussie muscle takes on the latest in European engine technology. In truth, the M5’s twin cam, 24 valve, 3.6 litre straight six isn’t all that new. It’s the latest development of the dry sump screamer fitted to the legendary M1 mid-engine sports car of 1978.

Nevertheless this remarkable powerplant, which develops 232kW at a dizzying 6900rpm and 360Nm at 4750rpm in its latest S38 form, has one of the highest specific outputs – 64.5kW per litre – of any normally aspirated production car engine in the world. What’s more, with the help of Bosch’s latest generation Motronic EM system the S38 also far exceeds Australia’s current emissions standards, producing seven times fewer hydrocarbons, 11 times less carbon monoxide, and 17 times fewer oxides of nitrogen.

And while the Group A’s specific output of just 43kW per litre is evidence of a push-rod, two valves per cylinder engine design which pre-dates that of the BMW by a decade, it is within the limitations imposed by its basic architecture, a highly developed powerplant. Maximum power of 215kW is developed at 5200rpm, while the torque peak of 411 Nm occurs at a high4800 rpm. The Group A’s torque advantage over the multi-valve M5 engine seems unexpectedly slim, until you look at the actual torque curves. Then you’ll see the home grown Holden has more than 300Nm on tap from just 1150 rpm, while the howling M5 doesn’t start to generate those sorts of numbers until at least 3100rpm.

More torque and less kerb weight – 1550 kg versus a hefty 1670 kg for the M5 – work to the Group A’s advantage over the standing 400 metres, despite significantly taller gearing. The M5’s short 3.9 final drive and 3.51 first gear slingshot it out of the blocks and to 60km/h a clear two-tenths of a second quicker than the Group A, which has a 3.45 diff and a 2.68 first gear. The M5 holds that holeshot advantage through second gear (2.08 vs 1.80) to 80km/h, but is two-tenths of a second slower to 100km/h and is eight-tenths slower to 120 km/h as all that mid-range urge and a closer third gear (1.29 vs 1.35) comes into play.

And the 400 metre times? The only one we’re absolutely certain of is the 14.8 seconds posted by the M5 at our regular test site. The Group A also posted a 14.8 second run, but the tight, tight schedule meant this was obtained on the main straight at Sydney’s new Eastern Creek raceway, where the last hundred metres are slightly uphill. Allowing for a quick three-four gearchange just before the finish line, we estimate the Group A should go the distance in about 14.4 secs on a pancake-flat strip.

Top speeds are largely academic – both cars will exceed Australia’s open road limit in second gear. But for what it’s worth, both the BMW and the Holden are restricted, the former by a computer chip, the latter by its gearing – to 250 km/h.

In theory, the M5 could pull 263km/h in top; the Group A, 375 km/h. No, that’s not a misprint. But while the Group A will run to the redline in fifth, a genuine two-five-oh, not even five litres of V8 torque is enough to pull much over 3500 rpm against the moonshot (0.50) sixth gear.

Fuel Consumption

Neither car will be especially cheap to run, if for no other reason than the fact oil companies charge a premium price for 95 octane premium unleaded fuel. With a 90 litre tank in the M5 and an 86 litre tank in the Group A, you can farewell 70 bucks at refill time.

Our time in the Group A was extremely limited, and the only directly comparable fuel figures with the BMW were obtained during a hard, fast 3am blast through central-western NSW. That the M5 proved more economical came as no surprise; that the Group A was not far behind did. In the final analysis the M5 averaged 19.4 litres/100km, compared with the 19.8 L/100 km consumed by the Group A. A further 700 km of mixed highway cruising, flat out track work and city driving in the M5 saw a worst of 18.2 L/100km and a best of 10.5 L/100km.

On balance the BMW is the more economical but not by much. The Group A’s better low end torque means you use fewer revs around town, and that long sixth gear enables you to cruise at 100km/h on the freeway with the big V8 ticking over at a paltry 1450rpm.

On the road

Things that go bump in the night: we pop over the crest at 180 and the lights flash across the yellow advisory sign pointing to a wicked dropaway left hander – 55 km/h. It’s hard on the brakes and back two gears, the big Commodore squirming over the humps and hollows in the road surface.

The nose dives straight for the apex quickly, cleanly, precisely – the moment the leather-clad Momo is pulled off centre. We’re right on the clipping point, hard on the gas and damn! There’s a bloody great lump in the road.

The front wheel thumps and tugs slightly at the steering wheel. The impact is somehow softer than expected, a tribute to the 40 different Bilstein damper combinations tested by Holden engineers before deciding on the Group A’s final specification, and the greater rolling radius of the massive 17 inch tyres. Then the inside rear wheel hits and geometry takes over. The Group A bucks sideways as the back axle is pitched into the air and steers the outside wheel. It’s quickly caught with a touch of opposite lock and a bootful of throttle.

But in the M5 a couple of minutes later, on the same line through the same closed-road corner at the same speed, all that happens is a muted thump-thump from the huge Pirelli tyres.

This is the fundamental dynamic difference between the two cars. Quite simply, the Holden’s archaic live rear axle is no match for the BMW’s independent rear end. But to leave it there is to sell the M5 short.

The BMW is superbly balanced; to the point where our resident race tester Kevin Bartlett pronounced it perfect after several hot laps at a cold and wet Eastern Creek.

That balance complements an outstanding chassis with beautiful-formidable accurate steering, 315mm disc brakes all round which are vented, cross drilled, ABS modulated and absolutely fail-safe. Adding to this is a smooth, slick five-speed transmission, roadholding and traction, especially in the wet, set new standards for a two-wheel drive car. On top of that, the ride quality and noise suppression achieved by BMW, in a car running 45 seres tyres and sports suspension, is nothing short of remarkable. Yes, it’s firmer and noisier than a standard 5-series. But not by much.

Next to the BMW the Group A feels and sounds like a car from another age. It crashes and thumps, rattles and roars. All three pilot-build Group As we drove suffered from excessive, unacceptable gearbox noise, the common VN Commodore problem of the doors squeaking on the rubbers and, of course, the inherent coarseness induced by the live rear end. Although not in the same class as the M5, the VN Group A is a huge improvement over its VL predecessor. It’s quieter through the air, rides exceptionally well considering its 45 series tyres and firmer suspension settings, and handles better, being far more precise and better balanced. But you can’t escape its humble origins, and in the final analysis the VN body simply isn’t as structurally secure a platform as the drum-tight BMW 5-series shell.

In reality, there’s not much between the two in terms of point to point speed over any given stretch of road. But the M5 is a lot easier on the driver. The transient responses of the steering and brakes are smoother, more fluid; the gearshift is more precise. It’s a car you guide smoothly with a deft hand, not take by the scruff of the neck and fling at the corners – so much so that it feels deceptively slow at first.

By contrast the Commodore feels a lot more sudden in its responses and the rear axle steer means you’re constantly making corrections through the wheel.

You drive this car all the time, not merely steer it. The brakes – a massive 330mm front, 280mm rear, developed locally by Holden Special Vehicles in conjunction with Brake and Clutch Industries – feel every bit as strong as the M5’s, but the lack of ABS is a worry on greasy surfaces. The wide ratio six-speed gearbox offers no practical advantage beyond pottering along flat freeways in top to conserve fuel, and suffers from an annoying vagueness in the gate, the result of not enough weight bias in the three/four plane.

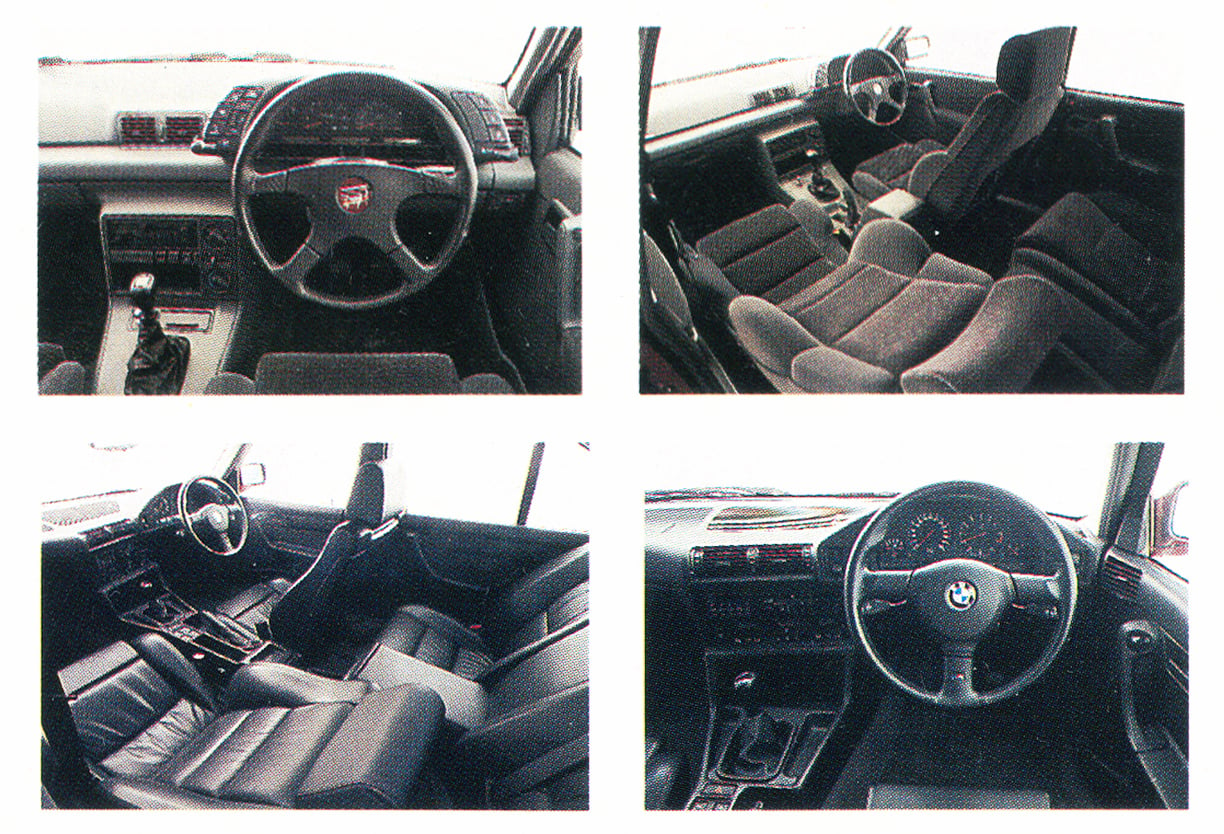

Interior

Neither car is startlingly different inside from its cooking cousins. If you order the standard five seat M5, the only clue to its performance potential is the superb leather-bound M-Technik steering wheel. Oh, and the slightly redesigned instrument cluster, which features a 300 km/h speedo…

The Group A’s dash is standard Calais fare, which gives you all the instrumentation necessary, but does little to enhance the go-faster image. Seats are very comfortable and supportive, but the M5 offers the better driver environment overall. The layout of the M5’s controls is ergonomically efficient, and enhanced by little extras like the memory in the electrically adjustable seats which also takes into account your exterior mirror settings, and the internal rear view which dips automatically at night.

The Commodore’s the roomier of the two. Rear seat legroom in the M5 is surprisingly tight, but your passengers can count themselves lucky you didn’t buy a Ferrari instead.

The Verdict

And that’s the bottom line – the M5 is the nearest thing yet to a four door Ferrari, combining exoticar performance, braking and roadholding, with the comfort and practicality of a top quality sedan. No other full four/five seater comes close, at any price.

Make no mistake – the VN Group A SS is fast. Bloody fast. And yet the legend which created this ultimate Commodore has also trapped it in a technological time warp. The VN Group A exists, live axle and all, not because it is the best Australia can do, but because Holden wants to win that one race of the year at Mt Panorama. It might be next year’s race car. But on the road it’s already yesterday’s hero…

What it needs is an independent rear axle, ABS brakes, the Caprice’s level of noise suppression, a decent base coat/clear coat paint finish and quality cabin furnishings. Buyers are entitled to that for $60,000. Until they get it the Group A road car will remain – on the world scene anyway-a terrific silk purse job performed on a sow’s ear.

We recommend

-

Classic Wheels

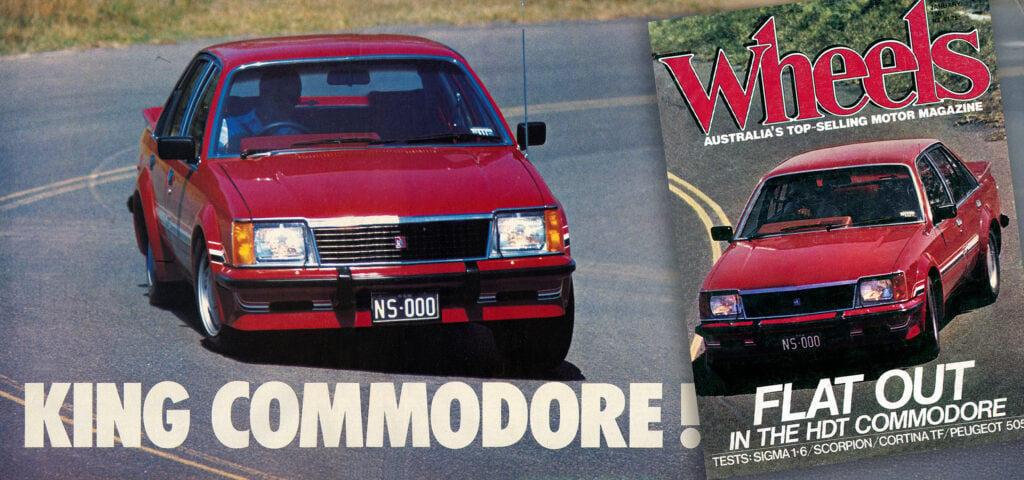

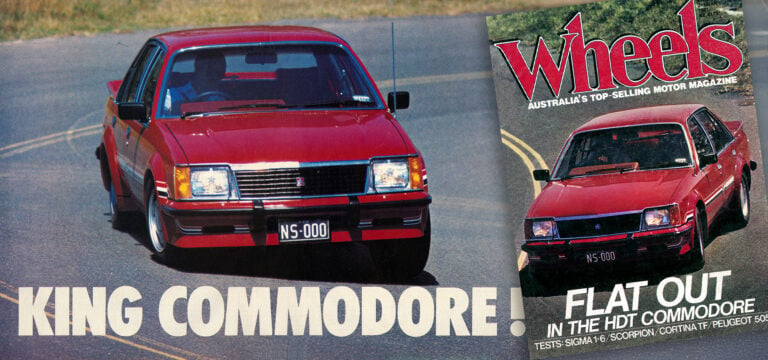

Classic WheelsFrom the Wheels archive: Flat out in Brock's HDT Commodore

Peter Brock's HDT Commodore was smooth, refined and quiet and yet it delivered a punch that couldn't be matched by any other sedan then sold in Australia.

-

Features

FeaturesHolden VH Group 3 vs Peter Brock’s VH 05

Peter Brock's best road and race car head-to-head

-

Features

FeaturesTop 10 performance Holden Commodores

From VB to VFII, we gather the hottest-ever Holden Commodores - according to us