If you’ve ever been told by your mechanic that your catalytic converter needs replacing, you’ve probably also had your eyes pop out of your skull when you were presented with the quote.

Catalytic converters, or ‘cats’ for short, are not cheap, but why are they so pricey when they’re just a relatively small component of your exhaust system, and one with no moving parts either? Why are they so important anyway? Allow us to explain the mysteries of the catalyst…

Catalytic converters started to become standard-issue in road cars around the mid-1970s, with Volvo being one of the first to adopt them, but they didn’t become commonplace until leaded petrol began to be phased out in the 1980s. The reason for that is simple: the gas that results from burning leaded petrol essentially destroy the catalyst’s ability to clean up exhaust emissions.

The main factor driving their adoption was the world’s slow realisation that vehicle emissions were literally choking the population and doing terrible things to air quality and the environment.

The picture above is of the Los Angeles skyline in the mid-1970s, and it’s hard to miss the thick brown haze enveloping the city and suburbs. That’s smog, back then it was mostly caused by vehicle exhaust. Acid rain was another unwelcome byproduct of emissions too, as smog interacted with the atmosphere and changed the chemical make-up of rain water.

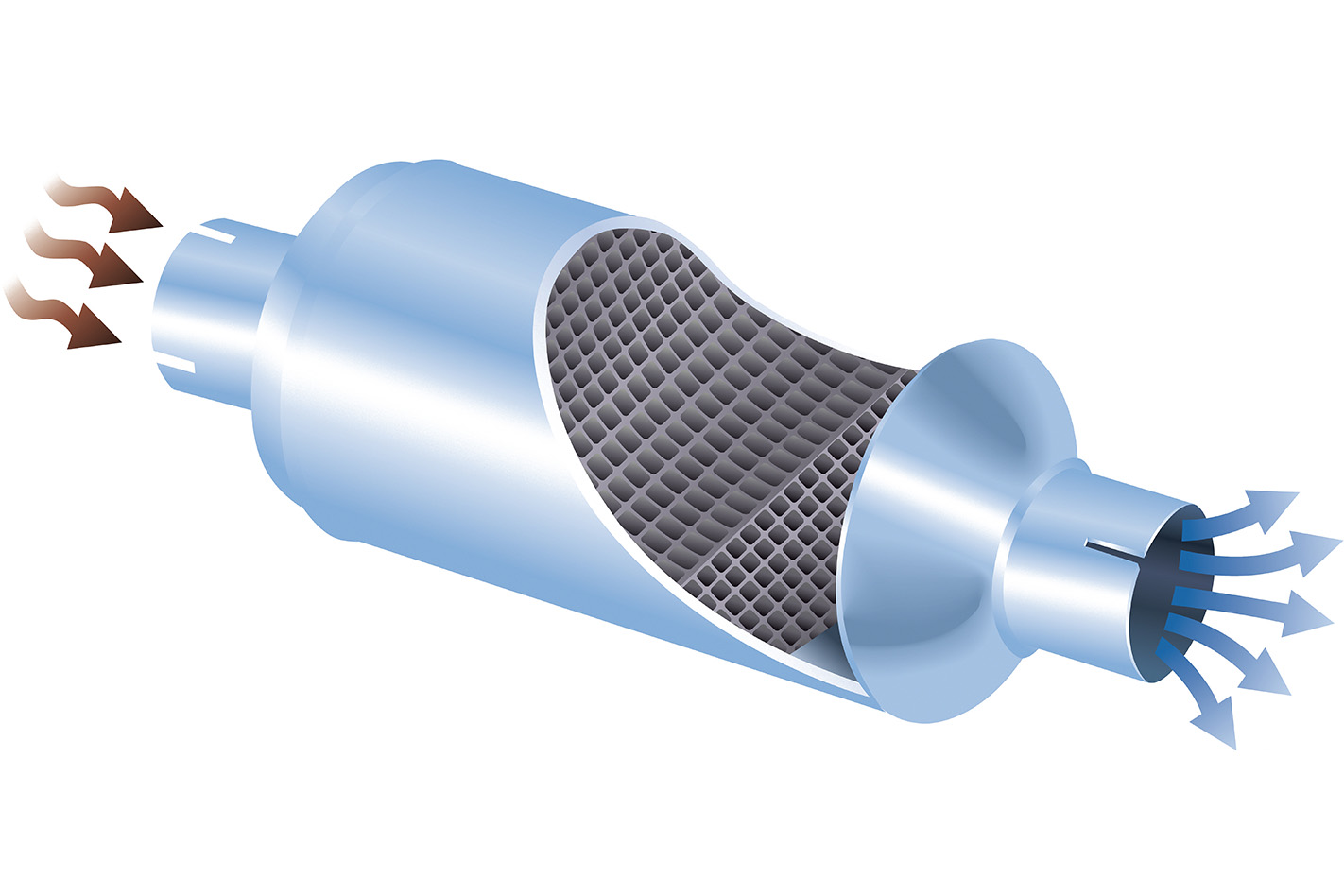

Enter the catalytic converter. By passing the engine’s exhaust gas over a surface coated with certain ‘noble’ metals that react to harmful emissions (and subsequently catalyse, or change, them into less-harmful gasses), a catalytic converter is able to scrub a significant amount of a car’s harmful emissions.

In fact, up to 90 percent of a car’s most problematic exhaust emissions can be neutralised by a catalytic converter, with unburned fuel, carbon monoxide and nitrogen dioxide being converted into less harmful nitrogen, carbon dioxide and water vapour.

It’s not totally clean of course, and with carbon dioxide being a major greenhouse gas a ‘cat’ can’t make a car completely green, but it certainly makes city air a lot more breathable for humans and animals. Besides, with all new petrol-powered cars and a significant chunk of diesel cars now equipped with catalytic converters, the net reduction in pollution has resulted in most major cities in the developed world no longer permanently enveloped by a blanket of smog.

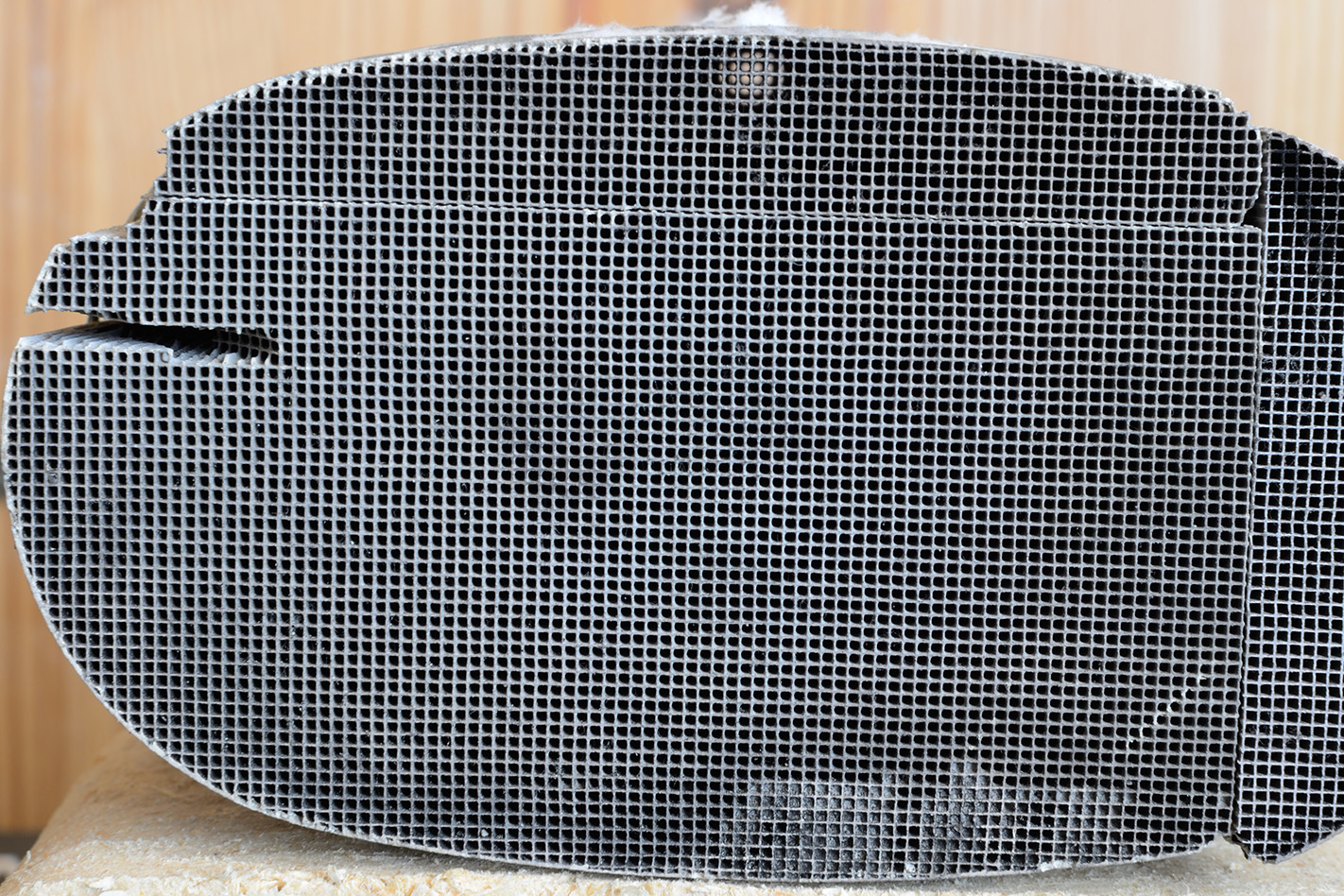

How do they work? There are no moving parts in a catalytic converter, with all of the cleaning action being accomplished by clever chemistry instead. Inside the converter is a thick substrate, often with a grid-like cross section (below), upon which a thin coating of precious metals like platinum, palladium and rhodium are deposited.

These metals are the actual catalysts, the part of the device that initiates the chemical transformation of the exhaust gas. Nitric oxide, carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide and unburned hydrocarbons – be they petrol, diesel or engine oil – all react with the metals inside a catalytic converter, and are quickly turned into other gases: principally nitrogen and carbon dioxide, but also water.

Some particulate emissions can be captured by a catalytic converter as well, though that’s not their primary function. Anyhow, separate diesel and petrol particulate filters have recently become commonplace and clean up fine particles that aren’t dealt with by the catalyst.

Downsides? They’re an expensive component, thanks to all of those precious metals used in their construction being, well, precious. They can be damaged by engines that are malfunctioning and perhaps burning more fuel or oil than they should, and there’s no method for their repair.

Also, the core is often made from fragile materials, which have a high temperature tolerance but are susceptible to impact damage from rocks or other objects passing under the vehicle. A damaged catalytic converter must be swapped, and replacements aren’t cheap.

The catalytic reaction requires a significant amount of heat to work. Most need an exhaust gas temperature of more than 400 degrees before the chemical reaction is working efficiently, which means that if you’re only using your car for very short trips – like ducking up to the shops for a few minutes – then a lot of your car’s harmful emissions are just going straight out the tailpipe as your exhaust hasn’t had time to heat up.

Also, with some of the gasses being converted into water, there’s a risk that excess moisture can accumulate within your exhaust and rust it out over time. Again, this is largely a by-product of very short trips. If your drives are at least ten minutes long from start-up to shut-down, then any moisture generated by the catalyst will just be evaporated off with exhaust heat.

Oh, one more thing: if you see a symbol like the one below appear on your instrument panel, it doesn’t mean that your jaffles are done – it relates to a catalytic converter fault, so go get it checked out.

If you avoid making lots of short trips and ensure the engine is kept in good mechanical health, there’s no reason your catalytic converter shouldn’t last the life of the vehicle. Mechanically simple yet chemically brilliant, the humble catalytic converter is the main reason why clear air still exists around major population centres.