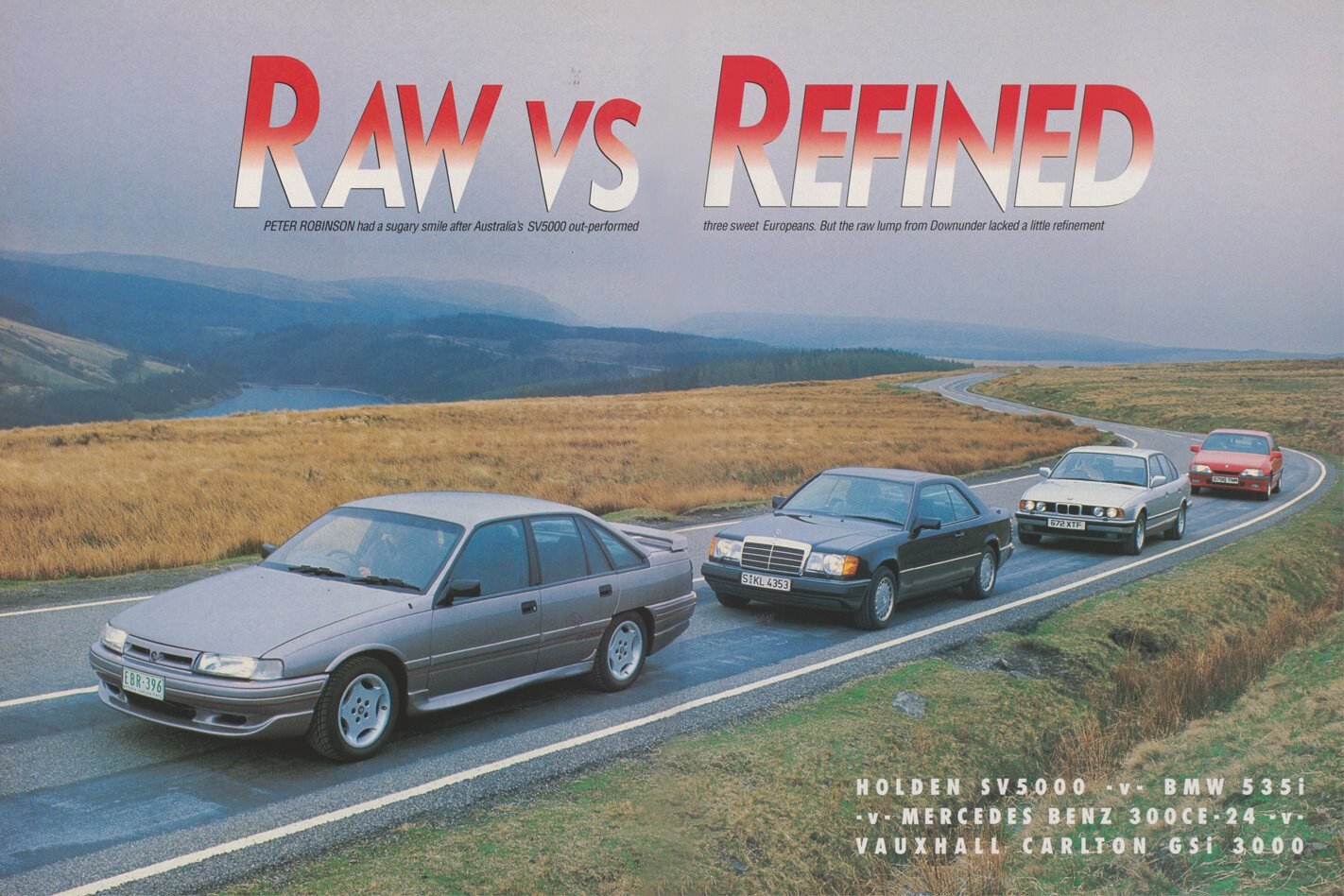

HOLDEN SV5000 v BMW 535i v Mercedes-Benz 300CE-24 v Vauxhall Carlton GSi 3000

“BLOODY HELL, this Holden‘s a big bitch of a car, ” or so I find myself thinking just before the Welsh road drops down out of the mist and we lunge forward together.

The frustration of limping through dense cloud ends and my right foot snaps hard against the accelerator. The transmission kicks down to third, then second with a jolt. The tacho needle instantly surges closer to the red, rear tyres snap sideways fleetingly on the wet road. Just a touch of opposite lock and the reins are tight again.

Since this is the only HSV Commodore in the Northern Hemisphere it’s wise to be prudent. But I can’t resist punting the Holden hard now the road is near dry. I pull the gear selector back to D, locking out overdrive and set about conquering this winding blacktop.

The Holden thunders. Easy now, boy, don’t get too carried away. Get the steering lock on early, yes even in fast corners.

You know there’s initial understeer that heightens quickly if you’re slow to dial the lock on. The Benz, Vauxhall and BMW maintain station, their chassis coping better with bumps that bounce the Holden around, their brakes firmer and more forgiving. You’ll never know how big a Holden Commodore really is until you punt one hard on the minor roads of Wales.

Dividing the town is a stream, the two halves connected by a humped-back bridge. It looks innocent enough so I miss seeing the warning signs. It’s too late, the Holden is launched up the curve. The houses on the other side of the bridge disappear, the windscreen is filled only by cloud.

It’s like being hurled out of a cannon. The steering goes light – that must be the front wheels airborne – the rears follow. We’re off the ground for a couple of seconds, literally flying, before the nose dips and the car lands four-square. No worries. So we do it again for the camera, EBR-396 soaring gracefully through the air. The rugged Holden has no objections. We don’t dare try in the Europeans.

Holden Special Vehicles’ SV5000 claims to be “the Concorde of sports saloons “. In the context of Australian performance, that’s true. But does the most potent Holden ever built really stack up against the European bluebloods? We had to find out. And there was only one way to do it.

With the SV safely freighted to Blighty, it was a hard job to find equivalent auto-trans sports/luxury- sedans. There is a prolific line-up of rivals on offer in Europe, many of which never enjoy the warmth of an Australian sun. But many pale into insignificance, value-for-money wise, when judged on size and performance.

Given the VN Commodore’s close relationship with the Vauxhall Carlton it was obligatory to include the new 24 valve version of GM’s 3.0 litre in this comparo. The twin-cam, in-line six is, incidentally, the biggest car engine produced by GM in Europe.

In this company we couldn’t ignore BMW’s 535i, almost universally considered the finest sports sedan in the world this side of yet another BMW, the awesome M5. Yes, we remembered that Wheels has already compared the SV5000 (January, 1990), but that was a manual and our four were to be automatics.

That’s why we ruled out the potent M5, figuring its legitimate rival in the Holden range would be the forthcoming six-speed VN Group A. In the end the sheer assertiveness of the 535i for the automotive role we’d defined meant we couldn’t ignore it. Enter one BMW 535i automatic, loaded with options but without the “S” bodykit, and on 225/60ZR15 German Dunlop D40s instead of 240/45ZR15 Michelin TRXs.

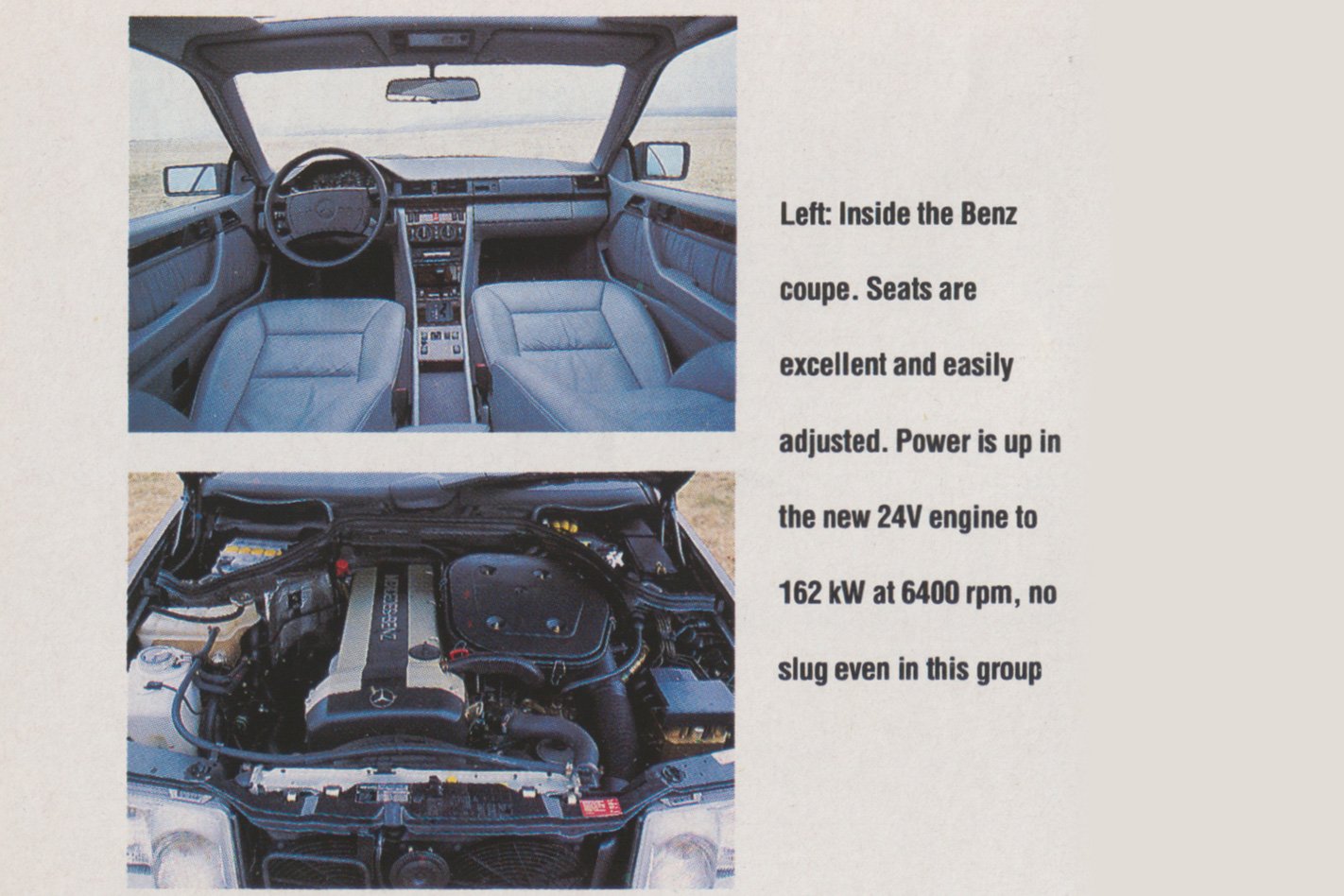

Our fourth contestant? A Cosworth Sierra? No, not really since they only come with 4WD and manual transmission. Volvo Turbo? Ford Scorpio? Alfa 164? Jaguar XJ6? Peugeot 605? Eventually one car seemed to stand out from this diverse pack in almost exactly meeting our guidelines, Mercedes-Benz’s new 300E-24. Our timing was awkward, however. We could have a manual sedan or a four speed automatic coupe from the factory fleet in Germany, for nothing suitable was available in England. We settled for a 300CE-24, appeased by. The knowledge that an 85 mm reduction in wheelbase and virtually the same suspension settings wouldn’t detract from its relativity.

THE CONTENDERS

Despite more than doubling the price of the humble Commodore Executive, HSV’s SV5000 still represents unbeatable buying in Australia. It could be a bargain in England, too, if the General would permit its export.

Holden’s problem is the coming Lotus-Carlton/Omega – a monster 280 km/h sedan powered by a Lotus-developed 3.6 litre 24 valve twin turbo six. HSV says it could sell the Holden for around £25,000 in Britain. GM says that’s too close to the £40,000 plus Lotus-Carlton, too close to justify homologation of Australia’ super-sedan.

It’s worth clarifying the Commodore’s lineage with Opel’s Omega/Senator range. Holden’s designers used the German car as the basis for the VN. Sure they widened the body and adopted the nose and tail to suit Australia’s marketing requirements, but fundamentally the VN is a recognisable derivative of the Opel. A close check reveals the front doors, for example, are interchangeable. Underneath the skin, of course, Holden’s engineers were forced by budgetary requirements to retain the running gear of the VL, and that meant a live rear axle. But instead of the in-line four and six cylinder engines used by Opel, Holden chose Buick’s 3.8-litre V6 and the masterstroke – the homegrown newly injected 5.0 litre V8. For the SV5000 it’s been tuned to boost power from 165 kW to 200 kW at 5400 rpm, while torque has gone from an impressive 385 Nm to a massive 41 0 Nm at 3600 rpm. Suspension and brakes also get a complete revamp to match the performance potential, while huge alloy wheels carry 225/50ZR16 Japanese D40s.

BMW’s six has a capacity advantage over all but the Holden. However, it is now the oldest engine in BMW’s line-up, so there’s only a marginal power edge over the Vauxhall. The oldest of this group, Mercedes W124 range enters its fifth year with subtle adjustments to appearance. But the crucial changes are the new Sportline option. This has firmer springs and dampers, more precise steering, wider 205/60ZR15 tyres, a smaller steering wheel, plus access to the SL’s four valves per cylinder 162 kW 3.0 litre six.

Here then are four fine cars, the top flight sports versions of existing family sedans, all front engine/rear drive and of a remarkably similar size and weight. All are aimed at the same enthusiastic, upwardly mobile buyer who craves sports/luxury, but still needs the practical advantages of four proper seats.

PERFORMANCE

You can put down your glasses. European hi-tech is no substitute for Australian cubic inches. Not now that they’re fuelled by a modern electronic injection system. The Holden simply drives away from its rivals. That’s to be expected given the SV5000’s power-to-weight ratio. Even so, the performance gap is more substantial in normal driving than the bare acceleration figures reveal.

Using the latest electronic Leitz Correvit-L VST timing equipment on Castle Coombe’s undulating surface, the SV5000 couldn’t quite match the times achieved in Australia. Still, 15.2 sees for the 400m – 0.3 sees slower – simply blows the others away.

None has an answer for the immediate acceleration of the Commodore, the product of instant torque from a rumbling V8 engine. And there is something incredibly unremitting about a car that pulls a mere 2000 rpm at the 112 km/h legal limit on UK motorways.

The high revving multivalve Europeans don’t stand a chance of staying with the Commodore from the traffic lights. Vauxhall and Mercedes take equal second place in this sector, so close through the gears and in kickdown for the differences to be meaningless. Both cover the standing 400m in 16.5 sees.

Many, I’m sure, will relish the sound. The enthusiastic driver finds himself using the flawless Mercedes automatic shifter more frequently than in the other cars, pulling back into third gear, preferably with little more than idle revs on the tacho to avoid the slight jerk. Even variable inlet timing can’t compensate for the lack of bottom-end torque, though this impression is stressed by the engine’s polished power over the last 3000 rpm.

Vauxhall ‘s solution is more effective. It has much taller gearing than the Mercedes – at 46.4 km/h per 1000 rpm fourth gear goes closest to matching the Holden’s staggering 53.8 km/h per 1000 rpm – though it, too, needs 4000 rpm to shine. But a more prompt throttle response than the Mercedes gives the impression the Vauxhall is quicker and makes it the easiest of the Europeans to drive fast.

Because of the sheer speed and the way the ratios harmonise together, the Vauxhall has the finest transmission in this group. Sport and economy shift modes can be selected by a conveniently placed button it) the top of the selector. This may well be the best automatic transmission money can buy in 1990 and reveals that Holden’s use of the Turbo-Hydramatic is limited if it wants to offer a state-of-the-art auto.

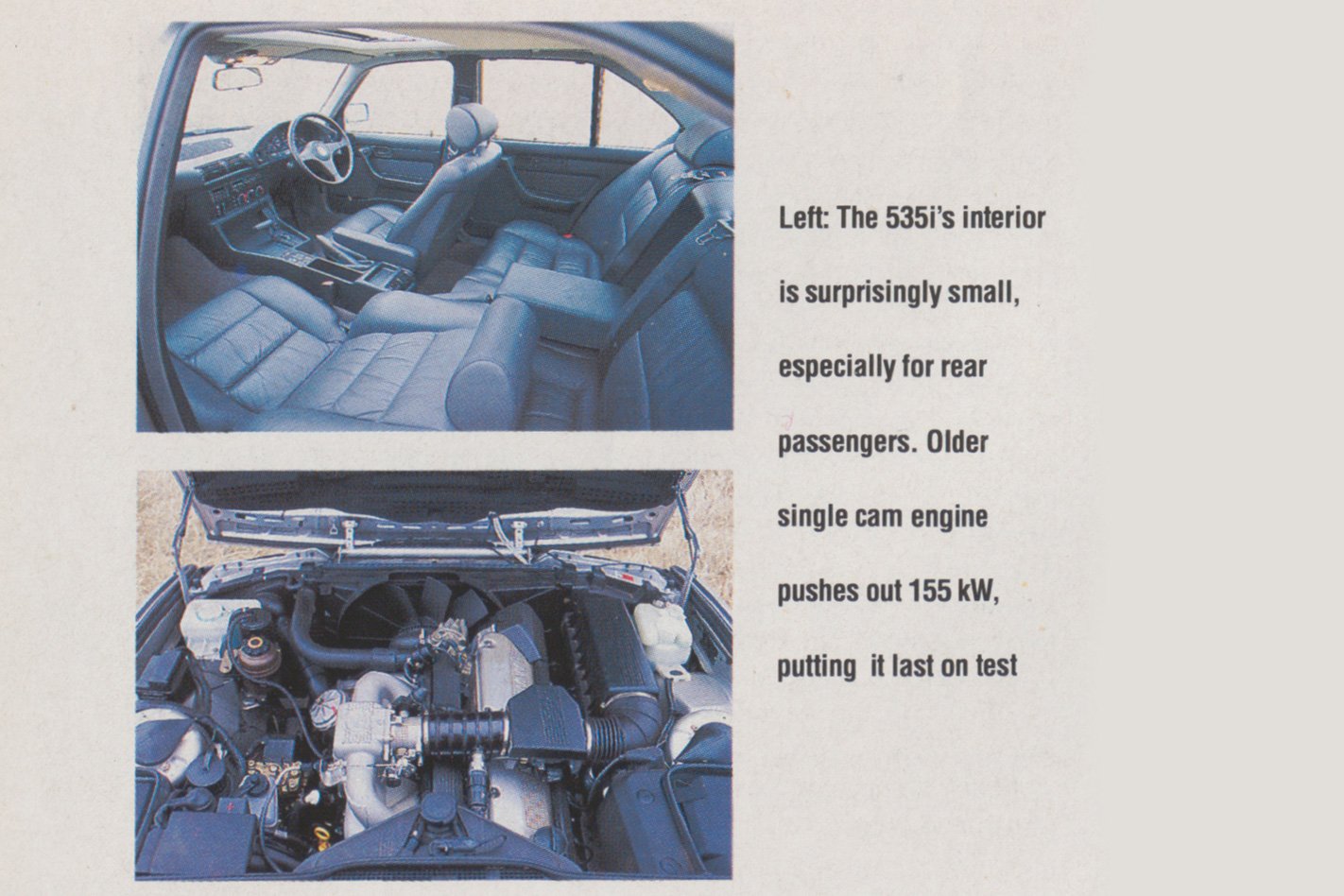

Which leaves the 535i to take up the rear, unsuccessfully struggling to break the 17.0 sec barrier. When testing the manual 535i, Wheels predicted a time of around 16.5 sees for the automatic, but the gap is invariably longer, even taking into account a location less conducive to optimum times.

Only a year ago this BMW 3.5 litre engine set the standard by which big sixes werejudged. No more. Both Vauxhall and Mercedes-Benz have finally overtaken BMW in outright performance and ultimate refinement. How quickly things change in the car business.

All four cars are capable of between 230-240 km/h. For most Australians, then, top speed is an academic question. But if you must know, the Holden is marginally fastest. All are happy to cruise at 160 km/h indefinitely.

FUEL CONSUMPTION

Naturally the Holden uses more fuel than the other cars. With easily the biggest engine/heaviest body, the V8 slurps through premium unleaded rapidly if you’re heavy with the right foot. Over two closely scrutinised fills involving all four cars, the differences were so marginal we’ve included only an overall average figure. We’re confident this will parallel the average owner’s experience.

With an average of 18.2 L/100km the Holden doesn’t look good. Constant-throttle cruising brings great benefits, of course, but few people will buy an SV5000 just to set the cruise control at 2000 rpm.

ON THE ROAD

We loved the Holden for its brutal, immediate power and the sensitivity of the steering; wallowed in the leather-bound comfort of the BMW on the motorways; savoured the new found precision of the Sportline Mercedes chassis; but the car that set the driving benchmark was the Vauxhall.

A bloody Vauxhall , I hear you say! Remember, however, this is an Opel , and not a Vauxhall like a Victor or a Viva or a Velox. Remember too, that men like Peter Hanenberger, who made Holden’s original RTS suspension work so well, are now running Opel.

The Vauxhall is near neutral in its handling, with a predictable and entertaining chassis, a difficult compromise to achieve. It has excellent body control, more roadholding than the Benz or BMW, and exceeds the Holden’s grip on anything less than a billiard smooth surface.

There’s only one important flaw in its make-up and that’s the steering. There’s nothing subtle about the heavy power system on the Carlton . Too heavy at parking speeds, despite the hydraulic assistance, the steering is also sloppy at the straight ahead.

ABS brakes, naturally, are standard, though the pedal has that slightly mushy feel inherent in most such systems.

You can drive all three Europeans hard for hours and never get fade or lock-up, just clouds of billowing smoke from under the front wheel arches of the BMW. Those familiar with a recent Mercedes chassis are in for a surprise when they try the W124’s Sportline option. How can such a comparatively insignificant change so easily convert this into a far more sensitive and decisive car to drive? Mercedes says it has changed the steering ratio from 14.61 on the standard cars, to 13.91 for the Sportline.

On paper, hardly a momentous modification, yet the steering is now consistent in its behaviour. There’s a far tauter, more agile feel, and more precision, especially at the straight ahead. The Benz has the best ride and copes brilliantly in absorbing bumps. The trade off is more body roll and slightly less composure under extremes, as when braking hard in a corner.

Four days in these car confirmed yet again that if the Commodore is to be truly competitive with European (and Japanese) big cars then it must get the Statesman’s IRS. There’s no real justification for a $50,000 plus Holden not having each rear wheel working independently. A live axle means a lively ride and an inability to cope with ruts and potholes that are hardly noticed in the other three cars.

It also means there’s more tyre rumble passed up from the road to the cockpit. Combine this with greater wind noise and you’ll see why the Holden never imparts the same impression of refinement or wellbeing as its rivals.

Up to nine-tenths the Holden has the best steering. It’s the most direct, yet still light enough for easy parking, while retaining a degree of feel. It firms up at speed, to such an extent that some might find its sensitivity excessive. Others will appreciate its utterly exact nature. Push further, when the steering wheel requires large lumps of lock, and it can go light, leaving the driver reluctant to press on. The fat rubber provides almost too much grip, for when the car hits a bump it moves around ungracefully, the understeer building up if it’s the front wheels which encounter the bumps first, and oversteer if it’s the rears. On the hard compound Japanese Dunlops fitted to the SV5000, wet European roads also mean a sudden build up in understeer before the tail moves out.

It’s young and raw, yet effective. There was never a time when the others cars could leave the Commodore behind – in fact, mostly it set the pace – and it was always the BMW that fell back due to its lack of performance.

ACCOMMODATION

If you must carry five adults then the Holden’s huge cabin is an easy winner, followed by the slightly narrower Vauxhall. The 535i has a surprisingly small interior – a six footer will reduce rear leg and knee space dramatically. The Mercedes can accommodate two adults if the front seat occupants are prepared to compromise a little. The 300E sedan isn’t as roomy as the Commodore, but equally it offers more rear space than the restricted BMW.

For the driver the choice is harder to define because all four achieve a high standard. The Vauxhall has the best seats. They are large, comfortable and supportive buckets, fully adjustable – as is the steering wheel for angle – and offer perfect lateral support. BMW’s designers put the driver a little too close to the door, but otherwise the driving position matches the Vauxhall, though the electrically adjustable seats aren’t quite as supportive. Mercedes’ seats improve with every model, those on the 300CE are excellent, no doubt helped by the simple and effective electric adjustment located on the doors. The Holden, too, has a fine driving position.

CONCLUSIONS

All of these cars are top drawer stuff, but where does the Commodore fit? In truth it offers a brand of motoring unknown in Europe. The SV5000 is a unique blend of raw power, stimulating yet effortless performance, a commodious body and fairly unsophisticated dynamics. At the price there’s no ignoring the fact that it is bargain-basement material, unfortunately unavailable in Europe. There are the habitual complaints about lack of IRS and ABS brakes, as well as the limitations of its more businesslike interior and fuel thirst.

Of the others we were surprised by the consistent quality of the Vauxhall ‘s chassis, and its fine engine’s blend of performance and economy. In terms of value for money in Europe, the Carlton is ahead.

No, in terms of overall competence and driver appeal, it’s the 300CE-24. The Sportline option retains all the Benz virtues, but brings with it greater driver involvement and a sensational engine that can only really shine in lands where the speed limit is realistic. But, do you know, if I wanted to drive any of these cars hard for pure pleasure, over a demanding road , I’d have no hesitation in choosing the fearless Commodore.

Refinement and finesse can sometimes go too far.