AUSTRALIA’S fastest and most expensive car is built like most skunkworks exotica… in a shed. A really big one.

How do we know? We are putting one together. Okay, that’s a lie. But we will fit it with a badge. Briefly, for a photo.

And it’s not really a shed. It only feels like one. It’s hard to grasp the HSV GTSR W1 without its symbolic importance. Which may be why Alastair, after quizzed about how he would photograph this feature’s opener, revealed he was expecting the W1’s birthplace to be… different.

Maybe it’s because he’s an Aussie-born pommy. Or maybe it’s because this is a world-class super sedan with a warranty-backed 474kW. But I honestly thought the same. I pictured R8s that float down production lines like toys pinched by a claw crane.

We thought we could get close as they waft by, tighten a screw here, buff a badge there, smile for the camera, and call ourselves line workers for a day. And tell you that, yep, we’ve built one.

Things like the interior, main body panels, and windscreen are already done. But a regular GTSR still has 40 per cent to go. W1s even more. So the first thing waiting at the Clayton plant’s doors is nothing like an HSV. It’s a VF II Commodore, yes, but it’s on yellow steelies, plugged with plastic bumpers, while grilles and vents are missing like it’s been plucked at by wreckers.

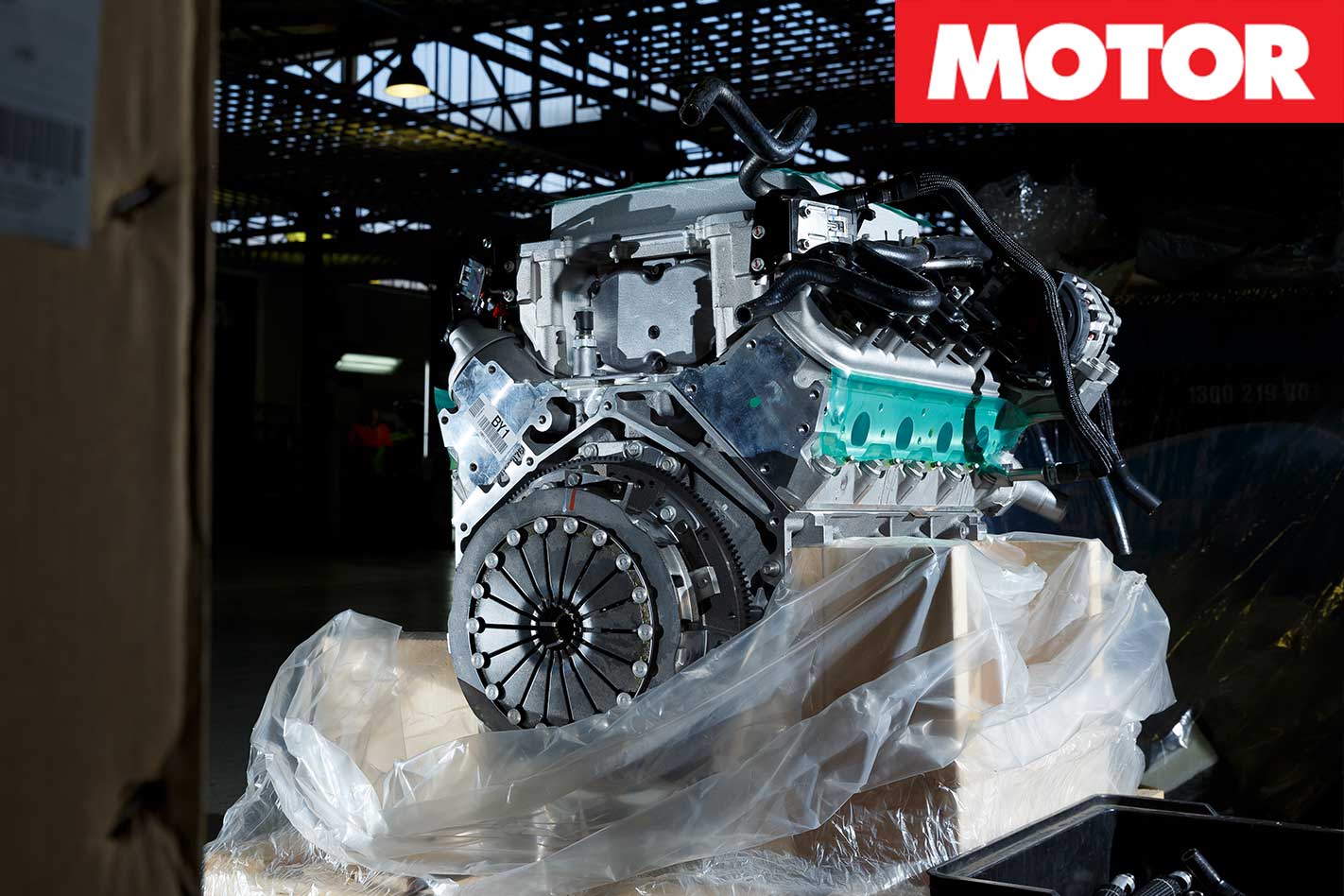

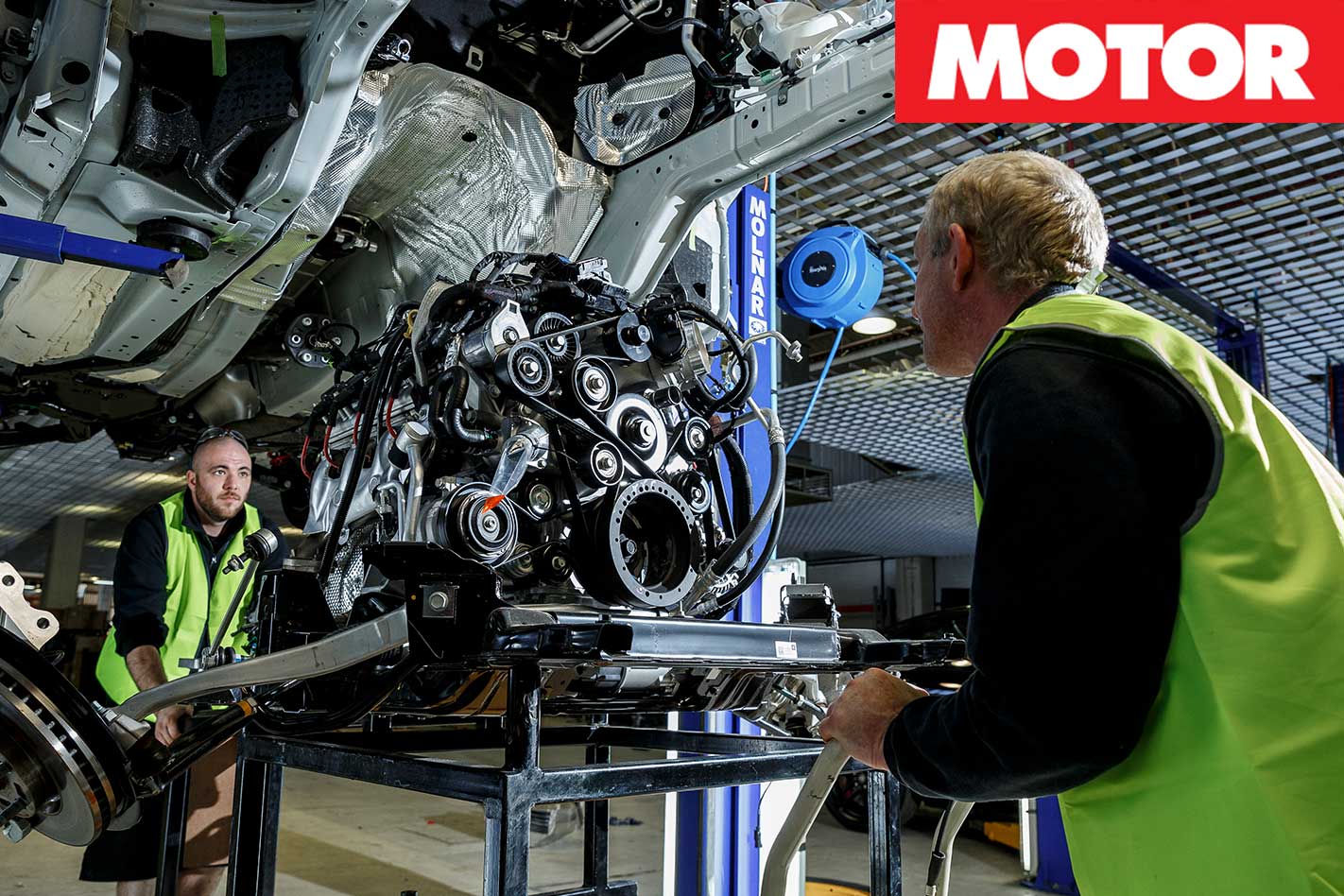

The W1’s LSA is swapped here for a rabid LS9 as Holden didn’t see the point in developing the tools, and process, to install them in Elizabeth. And the defunct LSA? We’re told they go back to Holden. Just like other parts of these ‘core vehicles’, like ‘slave’ brakes and wheels, destined for suppliers or the tip.

But they don’t just start waving an axle grinder. A 3D-printed jig is mounted on the bodywork before it’s trimmed, sanded, galvanised into a smooth new lip, then drilled with holes for the splash guards. This unlocks 3-4mm clearance for the new bags.

It’s a challenge. There are sometimes 130 people busy on these beasts, almost double the number in late 2016. Plenty have never modified a Commodore’s guards like this before.

The cafeteria line isn’t the only one trying to cope, cars sitting idle leapfrog to less time-intensive stations. Some arrive at the first with steelies on the front and 20-inch wheels on the rear, as if they’ve come from Sydney Dragway. And as we frantically pinball between stations, the colours of the W1s we document change from Light My Fire orange to Heron white.

Because the W1 doesn’t have adjustable suspension or an automatic transmission, the process is quicker than usual, freeing Nichols to select only the finest Alcantara. “I’ll go through five, 10 [steering] wheels if I have to,” Nichols tells me, “[it’s the] same sort of deal for the gear knob.” GTSRs get the scraps.

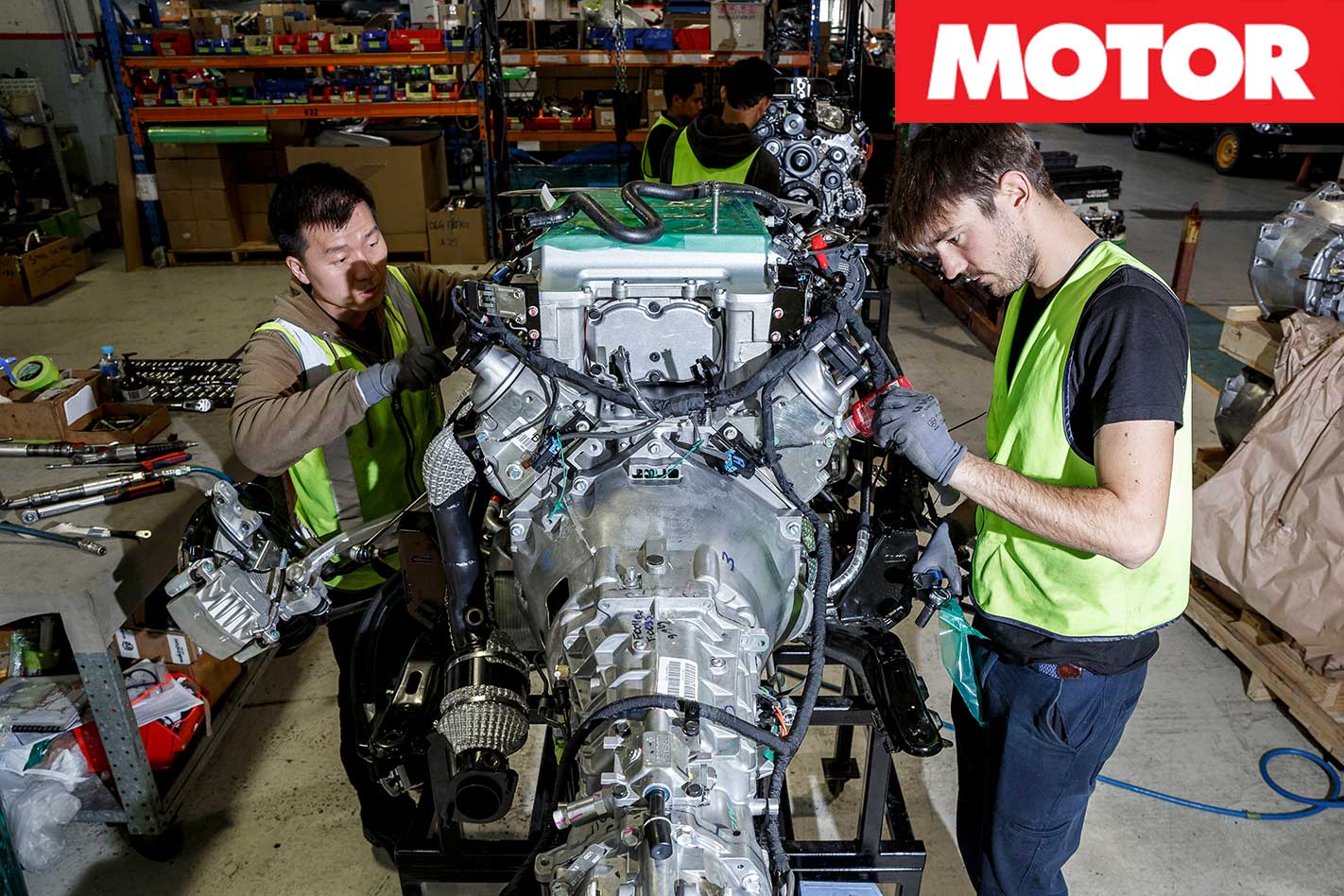

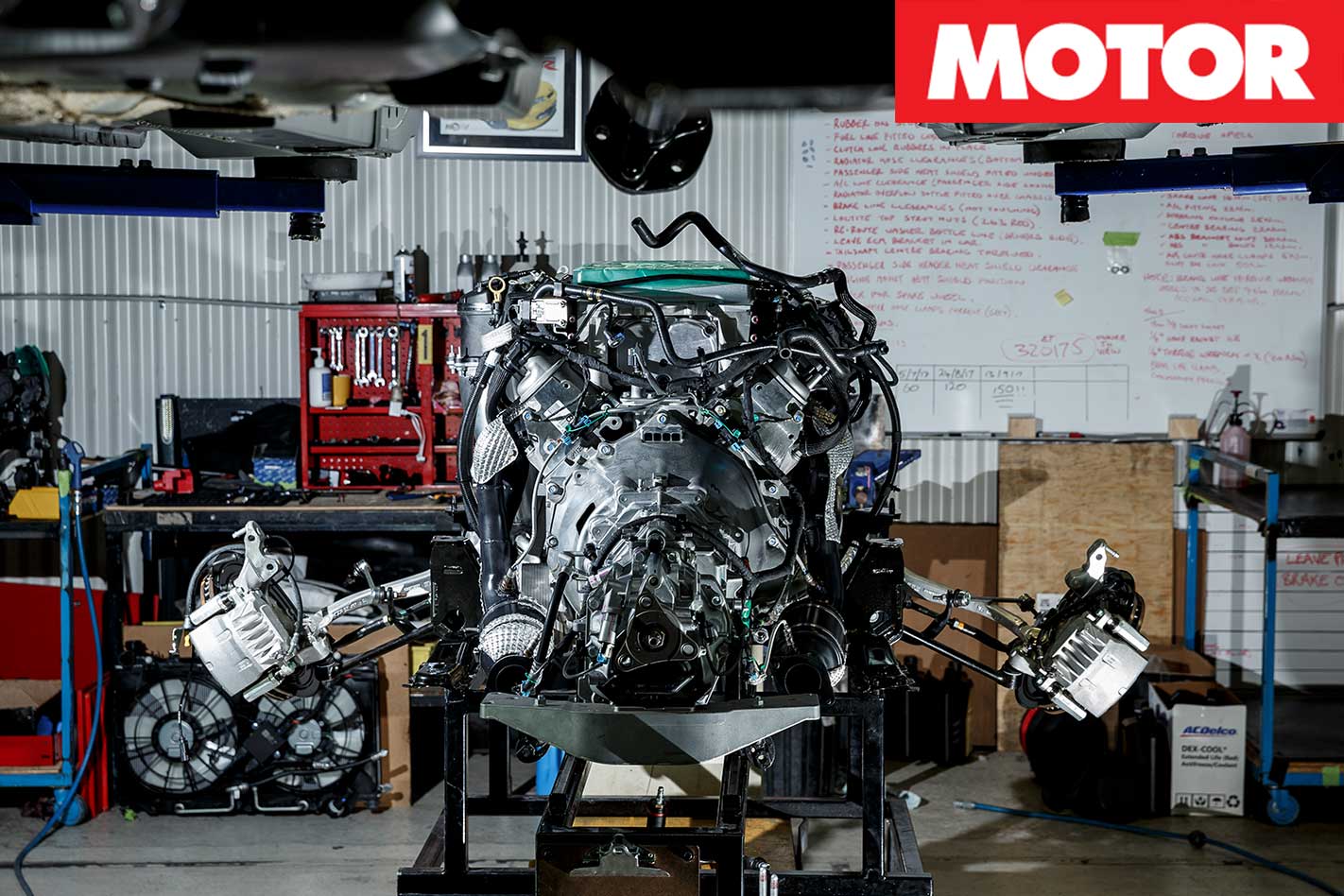

“There are three of four guys that do all of them”, Dave Reid tells us, after we undress an LS9 from its plastic cover. He oversees this section dedicated solely to the W1’s engine swap, which hasn’t existed since HSV last installed the W427’s powertrain itself in 2008.

A removed sub-frame and TR6060 six-speed manual await the LS9. The ’box arrives custom-built from Tremec in America with special gears strong enough for 815Nm. They’re married by four people, including Alex, a tall, softly spoken Spaniard who joined the W1 program after acing an aptitude test building a wheel, brake and suspension assembly. He tells me he left motoring journalism at home in search of more dough Down Under.

Next, the suspension’s standard ZF units are swapped for Supashock engineered coilovers, which are built on site. Body bits, including those pumped front wings made from ketchup-lid plastic, are painted separately before being fitted, with the W1’s matte skirts done last.

That’s soon corrected at station five, to the chagrin of long-timer Rodney Patterson. While Pirelli Trofeo Rs make those Superalloy wheels look like they could stick to the roof, he says the rear semi-slicks don’t wrap around the 20-inch wheels as easy as the standard Continentals. I offer a stiffer sidewall as the culprit. “They’re actually softer in the sidewall, it’s stiffer in the tread,” he corrects. His team saves them until the afternoon once they’ve warmed in a fan-forced chute to make it easier. Luckily, only three to four sets of Pirellis come a day, compared to 20 to 30 sets in total.

Gleaming four- and six-piston calipers await next. While our road testers think the GTSR’s AP Racing brakes, which clamp discs an inch bigger than the wheels on my 1.8-litre Integra Type R, were complete overkill, they make more sense up against 636 horsepower. The setup is so big, line workers can’t tend to the brakes unless the steering’s turned.

The W1 is hooked to a computer at the second-last station and downloads new modules so it can talk to its harder-working heart, feet, and legs before it’s looked over by the two most experienced blokes in the building. They run the final, and most thorough, inspection, checking everything against a documented process. Not that they need instructions. I’m told they can sub-in anywhere along the line.

The compliance plate, build plate, and DataDot markings come last, but everything pales to what I’m about to hear. People are waiting for me back at body line where I can plant a badge on the nose of a Heron White W1. As it turns out, though, no one’s waiting for me. The badges sleep in their heated draws, hiding as if they know my clumsy fingers could wipe tens of thousands dollars off the W1’s price.

The 11 Stages of the W1

Stage 1-2: “We know it’s somebody’s pride and joy, a collector’s item, so everyone handles these cars with absolute care and as if they’re our own cars. That’s where management gives us a bit of trust,” says Hassam Kakar at vehicle strip about cutting into the GTSR and W1 bodies. It’s a new process for his team.

Stage 4-6: Badges go on during station four, but Melbourne’s climate makes adhesion tricky. They’re kept in a cabinet at around 32 degrees, and can’t be applied to bodywork less than 16 degrees. Heat pads help make up any deficit in temp.

Stage 7-8: End Of the Line programming happens at station eight, where the W1’s electronics are updated with the right modules. The process is automated and takes about 22 minutes to reflash stuff like the TPMS and ABS software.

Toe to Toe: Lining up the W1’s big boots

HSV’s literally re-engineered the GTSR from the ground up to create the W1.

As we learnt during our time on the floor, the car’s wider footprint sports unique camber and toe settings with a much stricter tolerance on how much they vary. With those Pirellis generating so much more drag on surfaces, the W1 is given more positive toe.

Every car is aligned on laser-based wheel alignment technology that takes two people 20 minutes. The only challenge for the W1 is finding somewhere for the clamps to dig into the Pirellis. End-of-line inspectors will try to feel any error during their sign off drive.

Once done, the W1’s dampers are blocked so it doesn’t bottom out during shipping.