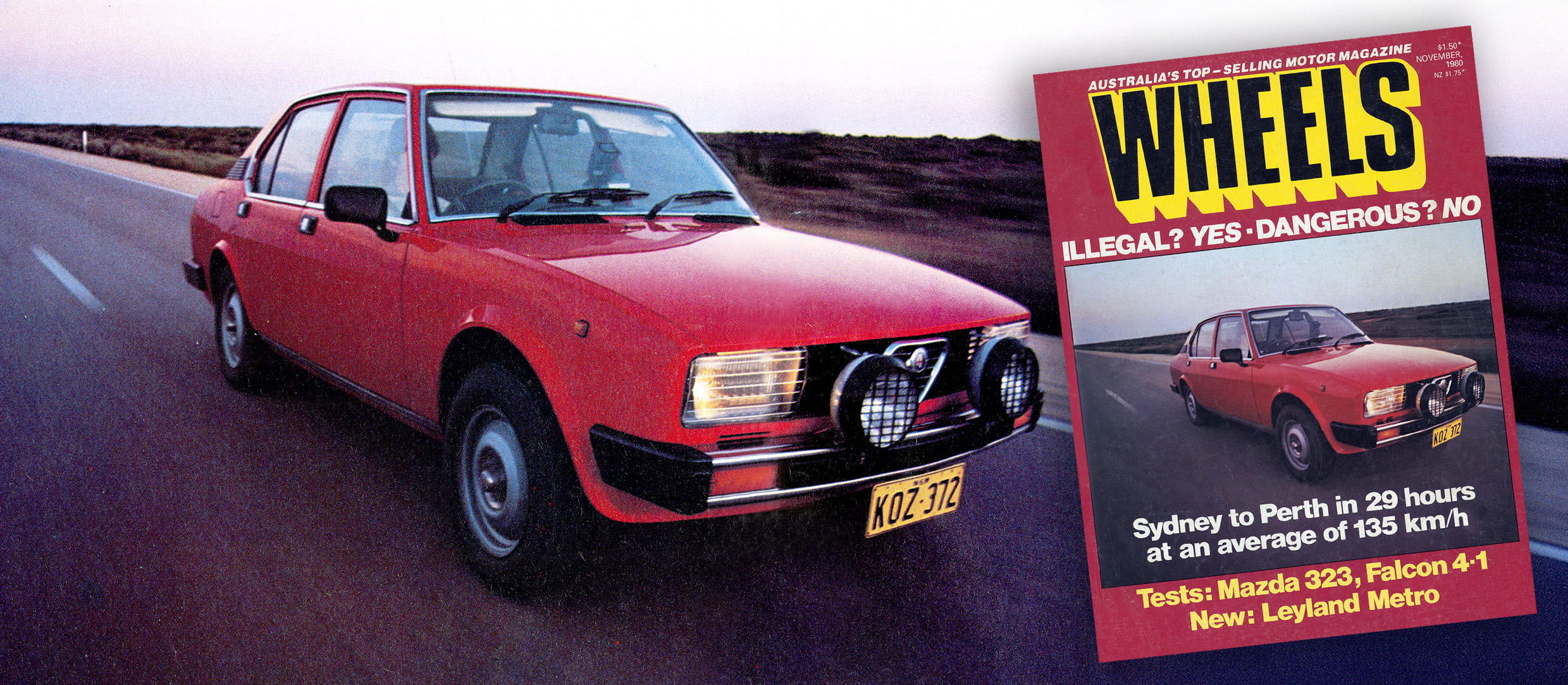

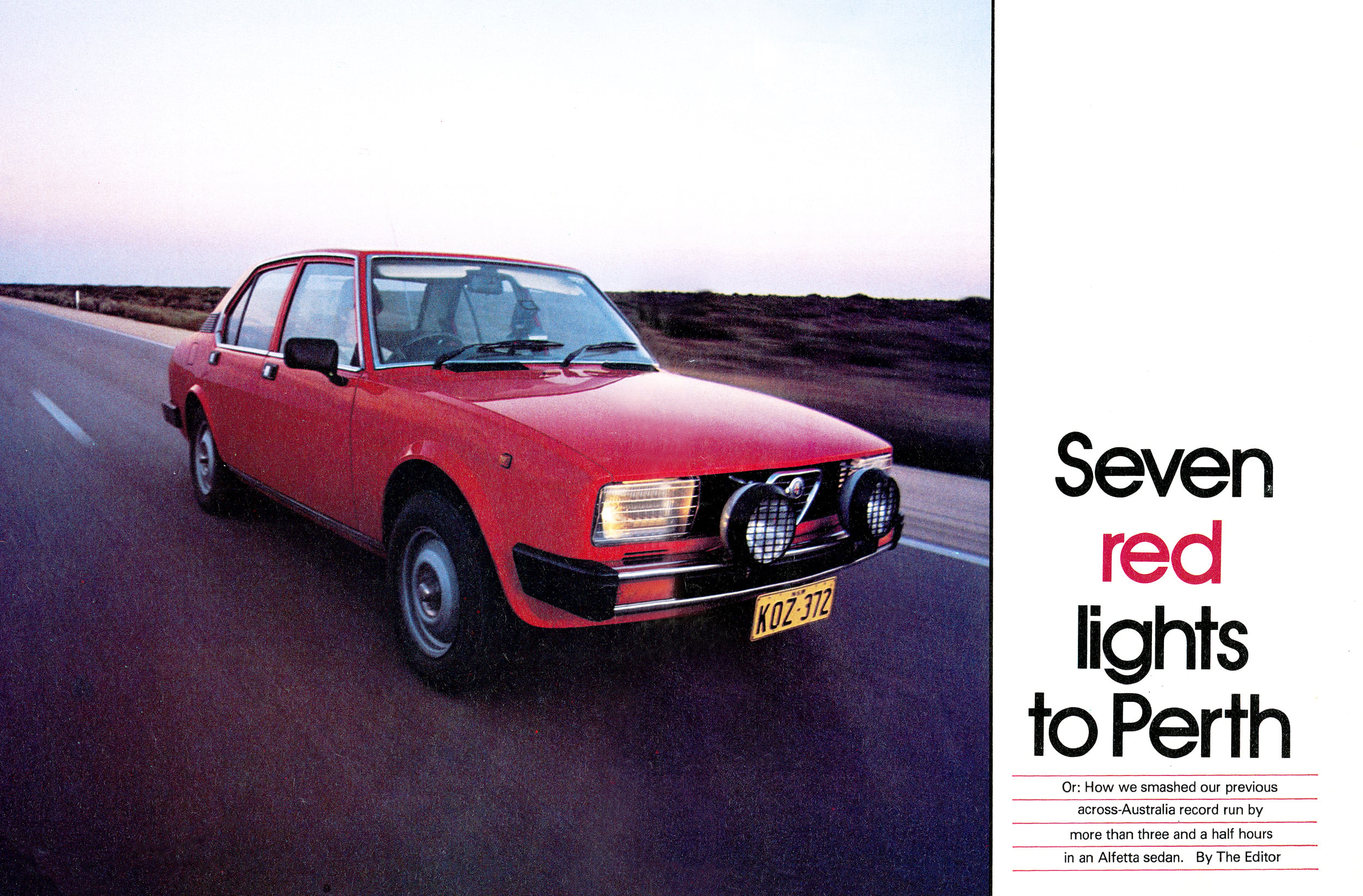

First published in the November 1980 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

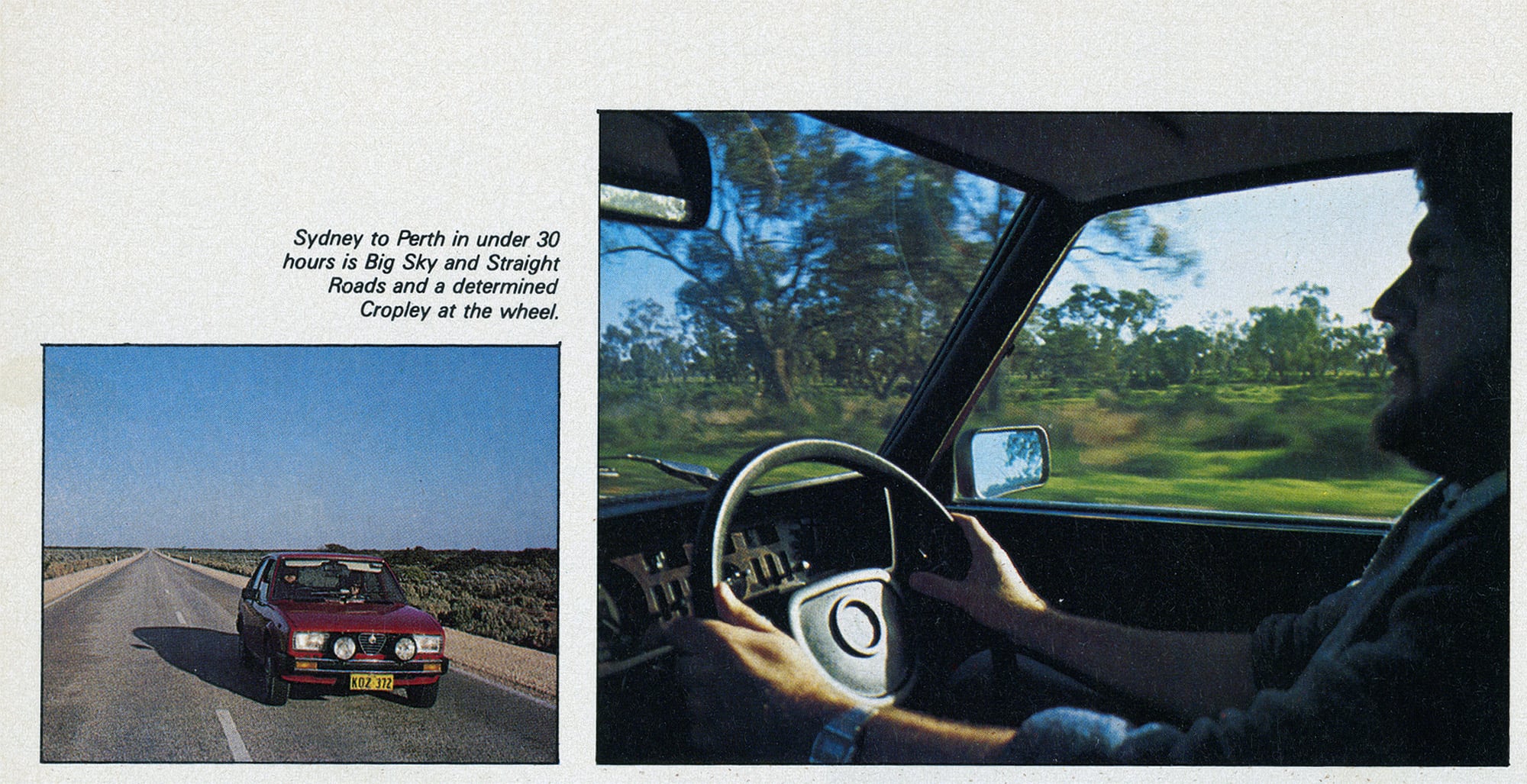

If I’m honest I’ll admit we did it for no other reason than because we wanted to. Oh, I can justify it on moral, ecological, and newsworthy grounds and will do so, just wait and see, but the reality is nothing so boring. It was to be an adventure, a giant self-indulgence of the very best kind for the simple fact is Steve Cropley and I wanted to see if we could drive across Australia more quickly than we did three years ago in a 4.9-litre Falcon.

We’d often contemplated the prospect of trying to beat our 32 hours and 56 minutes point-to-point time and drawn up lists of possible cars but all the talk had come to nothing. Cropley had gone off to live in England and the idea had shrunk into something we’d do One Day.

One day happened soon after our sometime illustrator and car designer David Bentley told me Brian Foley, Alfa dealer and car enthusiast, wanted to drive three Alfas from Sydney to Perth to show that it could be done in a 40-hour weekend and wondered if Wheels would be interested.

Brian listened patiently to my story of our previous trip and of my desire to try to do Sydney-Perth in under 30 hours and how I’d decided the ideal car would be a manual, five-litre Commodore with 2.6 final drive ratio and one of the 200-litre petrol tanks used by the Commodores in the Repco Round Australia rally. At the time Holden had limited the Commodore to the 4.2-litre V8 and, despite shuffling the cars again, I’d failed to come up with anything that had the right combination of long legs, reasonable economy and quietness, and the durability and robustness needed to cope with 4000km of non-stop driving across Australia.

Foley set about convincing me we could do it in an Alfa, though I’ll admit now I wasn’t completely persuaded and went along with the idea believing it might be possible but what the hell, I’d enjoy the drive until something went wrong. My doubts were to continue and be reinforced at least twice before we crossed the Swan River in Perth.

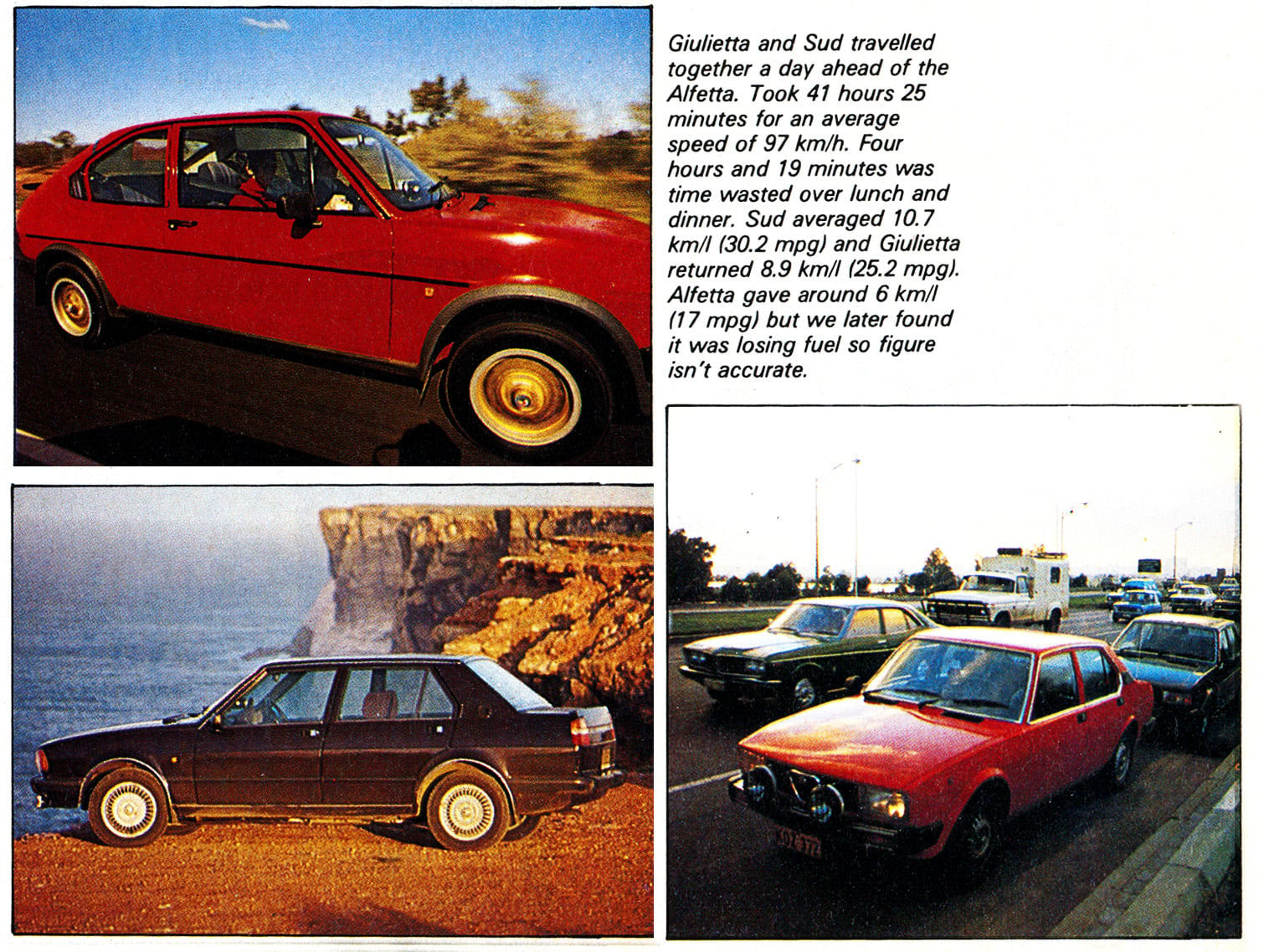

So the plot evolved. Wheels would drive an Alfetta sedan from Sydney to Perth quickly, with few stops and then only for fuel, while Foley and photographer Warwick Kent would take a Giulietta and a Sud ti for Christine Gibson (nee Cole) and Eileen Westley from Woman’s Day magazine on a more leisurely 40-hour drive.

Alfa offered us the Alfetta as a sedan because it figured a red coupe would be more likely to attract attention from the men in uniform and, although we weren’t told in so many words, we rather gathered that the sedan had to be sold while the GTV sold itself and the Giulietta was so new it didn’t need the publicity.

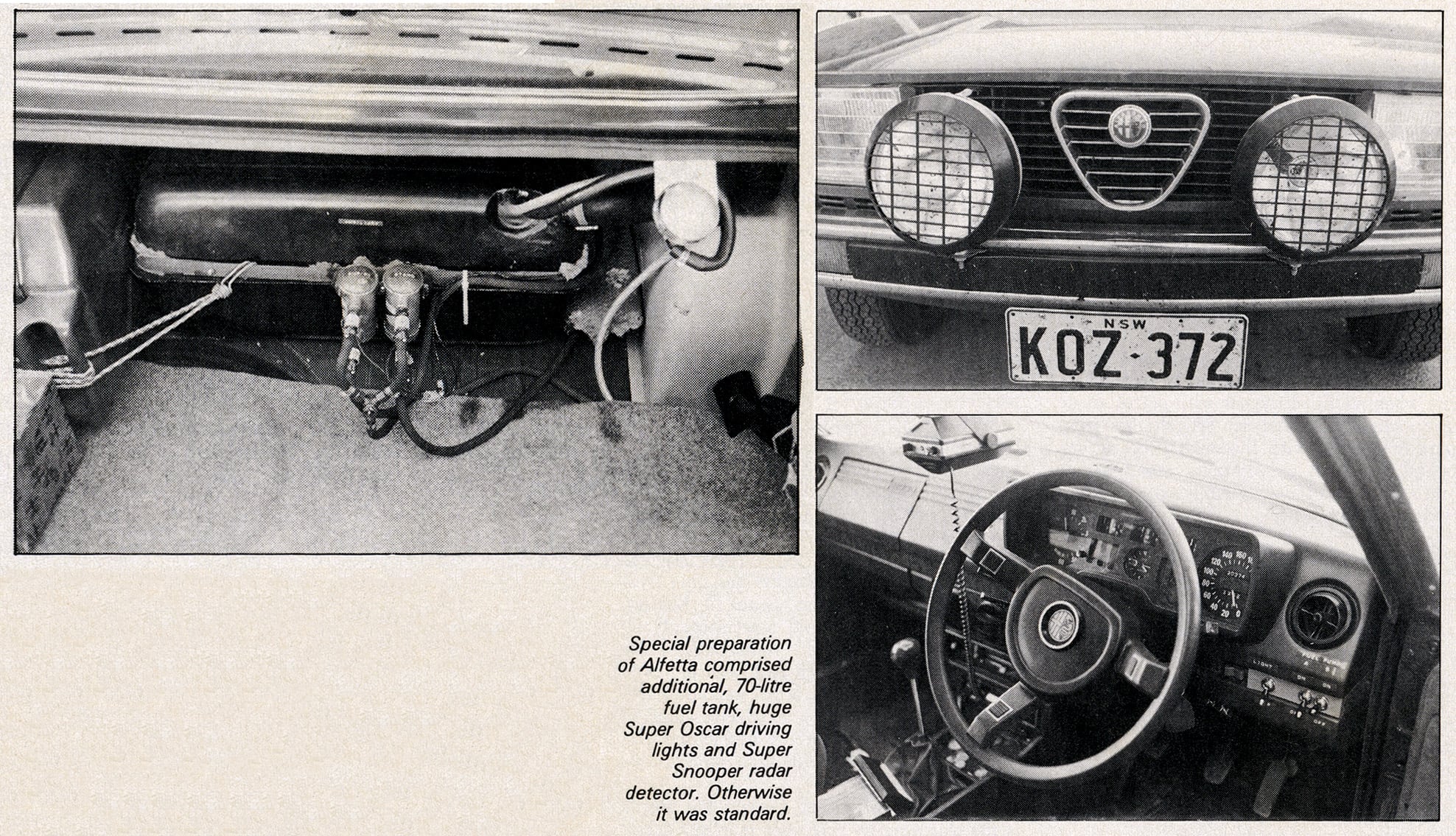

In 1977 we had ordered the Falcon, an XC, with the options we reckoned would make it suitable for the journey – a tall final drive ratio, Ford’s then-optional 125-litre fuel tank, driving lights, air conditioning and a laminated windscreen. Alfa doesn’t bother with such lists but there were still a few items we regarded as essential if we were to have a chance at knocking off our previous time.

Our Alfetta was a well run-in 16,000km old example, to which we added a 70-litre fuel tank to more than double the touring range of the standard (and woefully inadequate) 49-litre tank, with both the auxiliary and the regular tank having their own, independent electric fuel pumps; two large Cibie Super Oscar driving lights; Koni dampers for the front suspension; and a Super Snooper radar detector. Alfa also removed the pin which restricts the rearward travel of the front driver’s seat to give us more stretching room.

The work was all handled very professionally by engineer Reggo Rotondo and swarthy mechanic Lorenzo in a manner which induced a responsible attitude in the participants, in total contrast to our Falcon run when we filled the car with petrol, made some sandwiches and set off. Now we were part of a team with thorough preparations behind us, high expectations ahead of us, and a keen and knowing audience waiting in Sydney for a Result.

The question of a co-driver hung heavily. I wanted a quiet, patient, non-smoking, music loving mechanic who required no sleep, could drive safely for hours on end at over 160km/h, rarely needed to relieve himself and could get by on minimal sustenance. No compromise would be discussed.

Assistant editor Chris Gribble was away from the office for four days in the week before the run and somebody needed to stay behind to produce the magazine; Matt Whelan, who had just returned from his latest round-Australia run eliminated himself by smoking; and there were others who were excluded for failing one criterion or other. Thirty hours is a long time to spend in the compulsory company of an unwelcome person.

So, quite casually over lunch one day I mentioned the problem to Alfa’s Managing Director, Silvano Tagini, and mused quietly that what we really needed was a Cropley. And that is what we got. The big fella was coming home for a “works” drive. His first, our first.

It sounded, sounds, grand and the responsibility, I realised on his arrival, weighed heavily on the former assistant editor’s normally easy-going shoulders. And, backed by a complex schedule of estimated times of arrival and departure, average speeds, fuel costs and quantities worked out by Brian Foley, with the knowledge that we were going to be met in Broken Hill by Tony Vanderbent, an Alfa technical engineer, and in Port Augusta by Ilario Tichera from Adelaide Alfa dealer, Autosprint – just in case the car required attention – our adventure was taking on the proportions of a highly organised professional run. We began to feel like robots tuned to pilot the car to some predetermined unalterable schedule. What had happened, we wondered, to the relaxed Sunday drive feeling of our previous run?

Foley had us setting off at 3:30am one Sunday morning, although the other two cars were to leave together at midnight on the previous Friday. But on the Saturday night, over Parkinson, we decided to revolt in the interests of getting another half hour’s sleep and, especially, of doing our own thing. We would make up the time along the way. What confidence, what irresponsibility.

To add to the general air of light-headed frivolity (we hadn’t been drinking) I laughingly told Cropley of my drive home after collecting the Alfetta. According to the instruments the car had over-heated, had virtually nil oil pressure, and developed a hideous miss when caught in a traffic jam.

Frantic phone calls to Alfa did something to allay my worries and the car had run perfectly on Saturday, so perhaps all would be well. Cropley was not impressed. He had, he emphasised, come half way round the world to drive to Perth in under 30 hours and here was I telling him our transport was less than perfect.

Anyway, we had no alternative, the Alfetta sat in readiness, full of fuel and food – dried fruit, nuts and sandwiches plus fruit juices, and music from Bach to Beatles, although I had been told most strongly by Cropley that my squeaky soundtrack of the movie Casablanca, which had been my companion on so many long trips, was not allowed. To be consistent, we were once again to leave from the gates of the now-closed Terrey Hills tip on Mona Vale Road on Sydney’s northern outskirts.

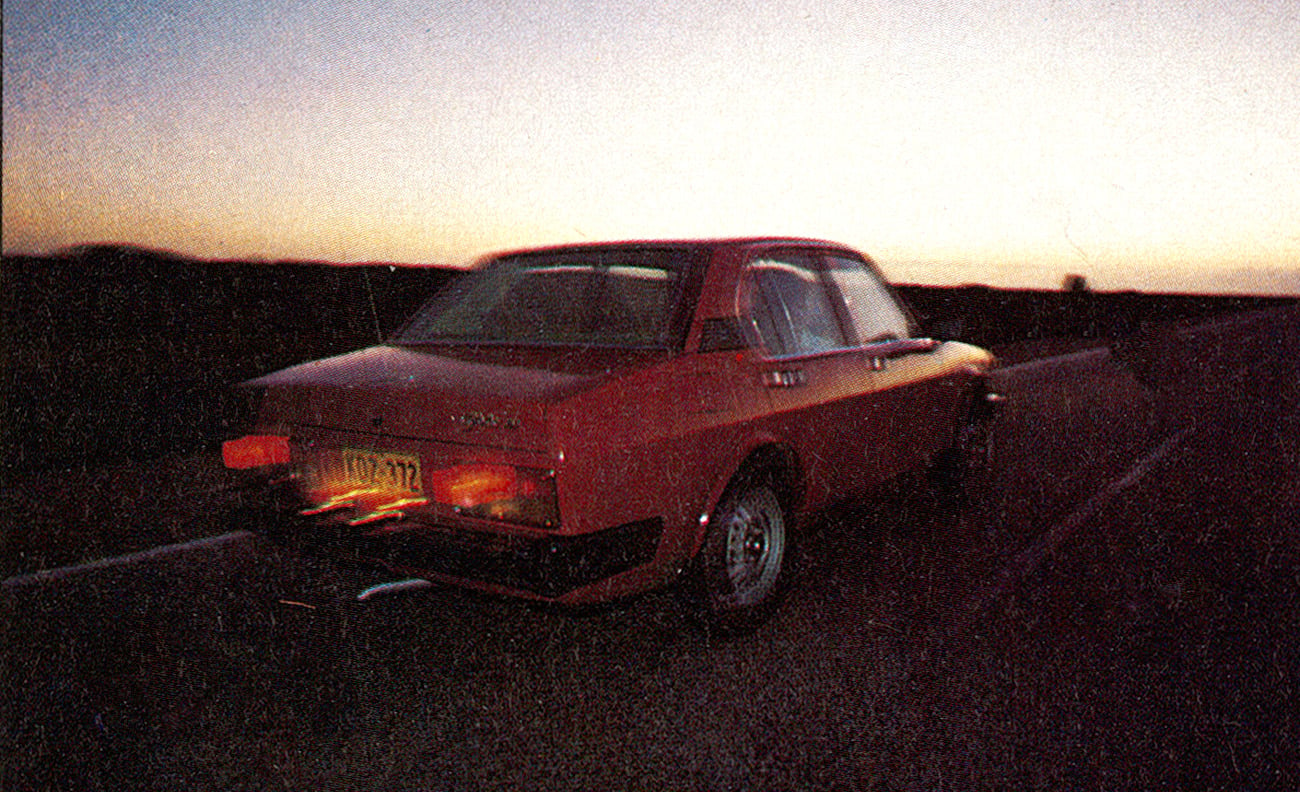

So we were off. Going beyond the people is the way Cropley described it in our notes. As we flashed past the tip gates my accurate-to- within-five-seconds-a-year calculator digital watch read 4:03.00. It was Sunday morning and we had a continent to cross.

Two kilometres up Mona Vale Road we caught our first red light. I looked at Cropley and suggested running the red but he pointed to the taxi approaching from the left. So we sat and waited and waited as first one set changed to green and then another until finally, after what seemed like five minutes, it was our turn. I muttered something about losing so much tiime, we should turn around and go home but Cropley pulled a determined face and I knew bed was something he was willing to forget for 30 hours.

I wound the Alfetta out away from the lights, checked that the radar detector was working and settled down to the task of getting out of suburban Sydney as quickly as possible. We missed red lights as if they were synchronised for our benefit and our progress was rapid until we swung out to pass a truck, only to discover a police car wedged in front of his bumper bar and inviting early morning speedsters to pass. We didn’t and for a few kilometres sat impatiently waiting.

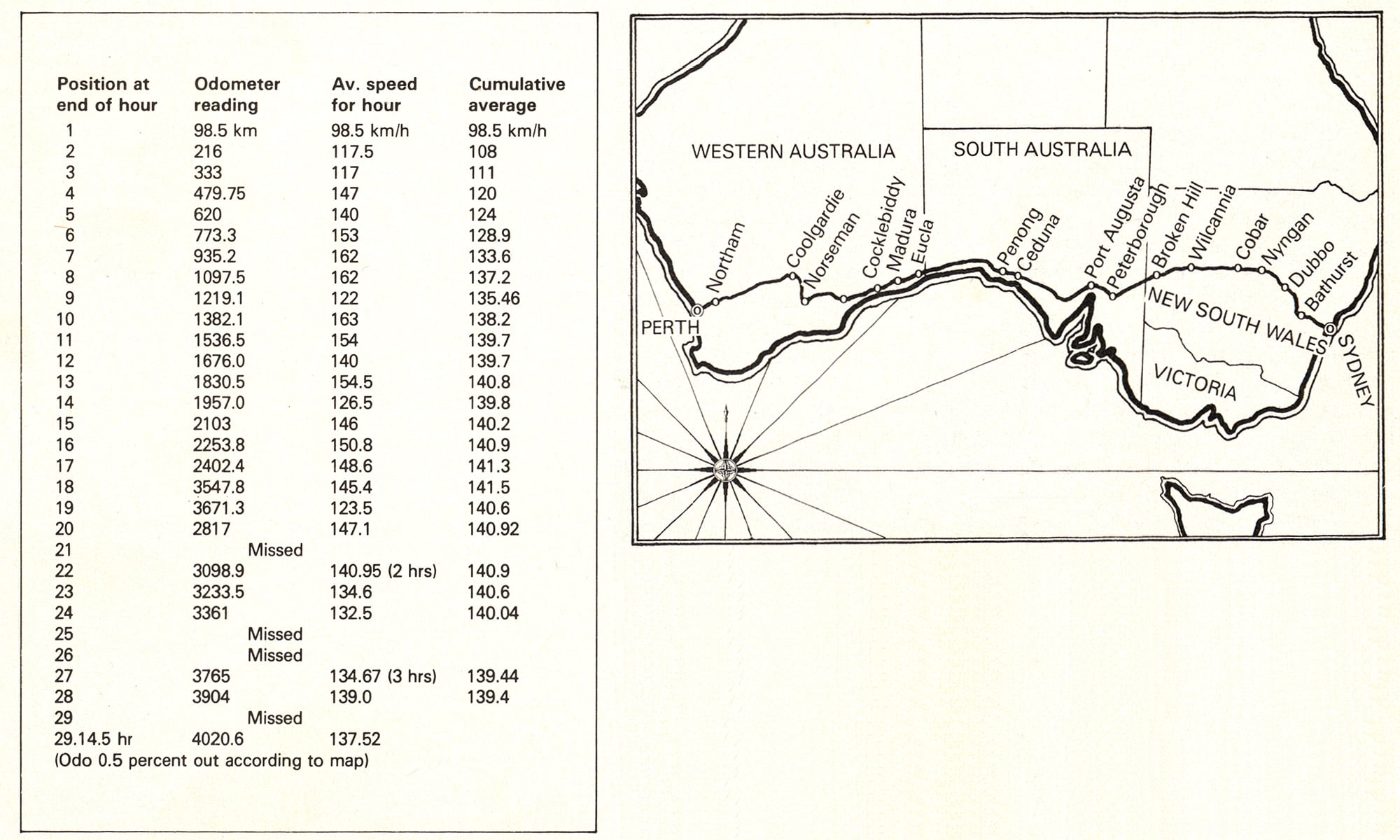

Once the police had gone off to the left we doubled our speed and were soon remembering events past at Amaroo and aeroplanes at Richmond before pressing on up Kurrajong and on to the Bell’s Line of Road towards Lithgow, the Super Oscars creating daylight in front of the Alfetta as it hurried along. In our first hour we covered 98.5km and we hadn’t begun to get serious about our driving.

Lithgow came and went so I took a chance on the long straights leading into Bathurst and prayed the Super Snooper was detecting. There was nothing to detect. The wind noise we had worried about wasn’t evident and we chuckled at Rotondo who had told us apologetically that he’d “only been able to do 160 around Botany” when testing the door seals after I expressed doubts about the Alfetta’s level of wind noise.

At the end of the second hour we had done 216km and had averaged 117.5km/h in the previous 60 minutes. Our accumulated average speed was 108km/h and the car was running perfectly and getting more accelerative as our fuel load lessened. Mostly it sat in fifth with occasional downward changes to fourth on steep climbs, only once and quite without warning it misfired at 3500rpm in fifth up a hill and we gulped. And that was all.

We rolled through Orange within 10 seconds of our schedule and decided “Fales” wasn’t a bad sort of a bloke and perhaps we should have done as he suggested and started at 3:30. Suddenly it was morning and our euphoria as the sun came up behind us was understandable. The first real stretches of open road were laid out in front of the car as we cruised at 4500rpm in fifth with the speedo needle hovering around 160km/h. It all seemed so easy and we resented the fact that one eye was never far away from the mirrors for the possibility of a law enforcement vehicle appearing detracted from the pleasure of the drive.

I had begun to explain to Cropley the entire point to our exercise was that three years ago we had done the trip in a 4.9-litre bent-eight family sedan and averaged around 12 mpg and today we were going to see if a tiny (relatively) two-litre four could not only do the run more quickly but achieve responsible economy as well. He was telling me to shut up, that he’d rather be listening to Julie Covington crying for Argentina, when the engine conked out in a long right-hander. A few simple calculations showed that we extracted 442km from the auxiliary tank (including some running around in Sydney after filling up on Friday night) and averaged about 6.3km/l (17. 7mpg), which we found mildly disappointing, although overseas tests had shown that at 160km/h an Alfetta gave slightly worse consumption.

Dubbo arrived with 412km on the tripmeter and our timepiece registered 7:34am. It was Cropley’s turn to drive and we pondered the enormity of what was expected of the man. He had never driven this Alfetta before and yet he was now expected to accelerate it to over 160km/h and maintain that speed without faltering. Two hundred metres after we’d picked our stopping point and rushed around the car to change positions, the Alfetta sat unhappily at another red light, our second. We could only glance at each other.

There was no hesitation as he ran the car out to our self-imposed limit of 5500rpm in each gear and 160km/h required no courage as we cleared the last remnants of the town and he set the car up for a fast sweeper.

“Sheeeeit, it does understeer ,” Cropley’s shouted words implied that I hadn’t warned him as his hands wound on the lock and he fought to keep the car on the bitumen but only just succeeded.

After four hours we’d covered 480km, having averaged 147km for the fourth hour, to give us an overall average of 120km, still well below the 133km/h average required if we were to break 30 hours.

Our first fuel stop was Nyngan, four hours and 38 minutes and 582km after leaving Terrey Hills and 28 minutes quicker than we’d done the same distance in the Falcon. An eight-minute fuel stop to take on 107 litres of fuel at 33.6 cents a litre cut our average for the fifth hour back to 140km/h but still took the accumulated average to 124km/h. We worked out that if we took out the eight minutes for the fuel stop we’d have averaged 161.5km/h for the hour.

We were now into what I believed would be the fastest section of the trip for we had daylight, two fresh drivers and a wide, straight and vacant road in front of us. Our cruising speeds crept up to 170km/h and for the next three hours we averaged 153, 162 and 162km/h to take our overall average to 137.2km/h.

The 595km from Nyngan to Broken Hill took just three hours and 45 minutes, so we’d just missed out on averaging 160km/h perhaps because… Somewhere west of Cobar we’d whistled over a hump at 170km/h to be confronted by a mob of sheep spread across the road with no daylight visible between the woollies. There was no way we wouldn’t hit one of them but Cropley, agile in defiance of his normal self, was down to fourth, stamping hard on the brakes in a full-blooded stop and somehow threading his way through the animals. We were down to 90km/h and had escaped before Cropley accelerated again. We didn’t have time to speak until it was over and then the talking was done with eyebrows and our music went back to Evita for the second time.

Gradually, we were coming into the red dirt country and even the bitumen road surface changed colour to a reddish-brown as we swept westward through wide radius corners that could be taken at 180km/h with the driver wishing for twice the power.

The incident with the sheep increased our caution over humps while cattle on both sides of the road around Wilcannia and ’roo carcases that littered the road forced us into a state of prudence. Our 170km/h cruising speed was dropped back to 150 because it made us feel more comfortable although we couldn’t decide what difference 20km/h would make if we were to hit a cow. Worse, while 170km/h helped our average speed, 160 seemed to be hurting the average and 150 was downright slow and would obviously mean we’d fall behind schedule, or so it seemed.

It’s a strange sensation. There we were, remote from the outside world through which we were cutting at 170km/h and yet, while the road was clear, it felt motionless. In that situation it is only when you have to stop quickly that the speed becomes apparent and in a split second, everything is exaggerated from being an inert position to one of an accelerating velocity of frightening potential.

Broken Hill was our next fuel stop and our first pit stop. Tony was to meet us at the 60 km/h sign on the east side of the town, follow us into the first service station and check over the car. He had flown up on the midnight plane after driving back to Sydney from Queensland on the Saturday morning.

The white rent-a-car was waiting as expected. Our pitstop routine cleaned the windscreen, filled the car, checked the oil level – none was required – and enabled us to tell Tony of the 15psi oil pressure in fifth gear at 170km/h, although it wasn’t consistent and sometimes rose to 30psi, and of the minor trouble we’d had with the fuel switchover which, for some still unknown reason, reduced our speed from 170km/h to 150km/h unless we chopped from one tank and fuel pump to the other a couple of times. We were told not to worry and eight minutes later and $37.38 lighter of wallet, having paid 36 cents a litre, we pulled out. Tony had travelled 2400km to say “no worries” after eight minutes’ work. It was one way of spending a Sunday.

We were in Cropley’s home town but there was no time to say hello nor for the once compulsory escorted tour of school and home and girlfriend’s place, without them we were through and gone and Broken Hill seemed small and restful and we decided we knew why people live to be 100 in such a place. Even the busy intersection that had been the outer limits for a younger Cropley on a pushbike seemed deserted but the wide streets and verandas and tin roofs and dusty hills remained unchanged. London was a world away.

Despite our hurried stop the ninth hour produced only 122km and dragged our average speed back to 135.5km/h. The two red lights we caught within 100 metres in the main street of The Hill didn’t help.

Cropley warned, as he did last time, of the treacherous 50km from Broken Hill to Cockburn on the South Australian border. But many of the hidden dips and off-camber crests had been softened and there wasn’t quite the same evidence of desperate braking and sump scraping of three years ago. Still, it’s not a piece of road to tackle late at night if you are in a hurry.

The road to Yunta was smooth, wide and easy but that’s not the way Steve remembered it. He even talked over Evita to fill me with tales of his father’s Consul and the nightmare trips to Adelaide that took all day and most of the night and involved rations and carrying water and getting bogged for hours in the endless mud. I believed him, but it took some imagination as we rolled on with 170km/h on the dial. Adelaide, if it were our destination, was only three hours away. Our tenth hour gave us our best average speed of the trip, 163km/h.

As the sun moved into the western sky we became aware of the nasty reflection in the windscreen from the top of the instrument panel. Of the rest of the car we had no complaints. The seats were still comfortable, a remarkable feat and one we hadn’t predicted, the suspension soaked up the few bumps we’d come across and the Konis had muffled out any of the dramas that might have been when we hit the occasional dip or drain too quickly. Only the continuing frustration with the fuel change-over caused us any alarm.

From Peterborough we changed direction from south-west to north-west and headed off towards Port Augusta through country that changed its appearance far more frequently than anything we’d seen since Orange. Even Horricks Pass – incorrectly called the Pichi Richi pass by Cropley on our previous trip – had been resurfaced and redirected to abolish the sharp dips and dangerous curves and is now an entertaining piece of road. But I remembered our load and Cropley reminded me we were only a third – just a third, it was hard to believe – of the way to the Indian Ocean so I backed off but made a mental note that it would be included the next time I’m on my way to the Flinders Ranges.

It was the endless left-handed sweeper that takes you out of the pass that had me singing the road’s praises. Then it was down into a huge basin, with Spencer’s Gulf coming from the horizon on the left, almost to the middle of the scene, and the southern tip of the Flinders marching down from the north. It is simply one of the biggest views in the world.

The road rushed on and the Alfa built up speed and without asking permission or even hinting that it might be fun I let the speed build up to 190km/h before buttoning off and admitting my guilt. Cropley, of course, knew.

Our arrangement for the second pit stop in Port Augusta was the same as the first, we would be met at the first 60km/h sign outside the town, but there was nothing to check so we decided to pull up alongside the Adelaide Alfa, convey our thanks and then press on. Three faces peered out of the car as we drew alongside. No, we said, there’s no trouble, the car’s running perfectly, everything’s okay and thanks heaps. They smiled broad Italian smiles, wished us luck and set off on the 300km back to Adelaide. The Cropley resolve was strengthened by their enthusiasm.

Port Augusta dealt us the only heavy traffic we were to sight until we reached Perth. It was Sunday afternoon and the weekly ritual of a drive in the country had the entire population on our road. They meandered and rambled, chopped in front of us, slowed down at the merest hint of a corner, and forced us to a halt at our fifth stop light. We were not pleased.

The prospect of a fuel stop in Port Augusta had been discussed, recommended by our schedule, but rejected on the grounds that while we had adequate supplies of fuel we should continue on because we now understood just how much even an eight-minute stop meant in terms of lowering our overall average. More importantly, we took the right road out of town and went down to Whyalla and so saved about 30 minutes compared with our Falcon trip.

At 5:45pm local – 6:15 Eastern Standard – time we pulled into a service station at Wudinna, 1858.9km from Sydney. The zealous rushing of our first two stops had given away to a methodical thoroughness as we took on 112 litres of fuel at 38.8 cents a litre. The stop took nine minutes and we forgot to clean the windscreen. Tiredness was creeping in on us.

We were told the police were thick on the ground in Western Australia, and had been advised against speeding, advice we knew we’d ignore. The ’roos, the service station attendant said, were worst around Norseman. Cropley took over and we headed into the darkness. He talked quite seriously about conserving fuel by driving at “160km/h and no higher … at least while visibility lasts”, and we knew that despite the time we had gained over our schedule – we were running about 30 minutes ahead of the time needed to break 30 hours – we were still less than half way and had the night and weariness ahead of us.

The sun was now directly above the road and Steve had to strain through the bugs and insects that do their best to limit vision. Ever so slowly, the sun moved across to the left, or was it the road moving to the right, as the sky behind us turned black? It wasn’t until Ceduna, 200km up the road from Wudinna, that the orange ball disappeared into the sea at 6:45pm Sydney time.

The windscreen was now covered in splattered bodies and I reckoned we should rush into a service station and clean the glass without buying any petrol. Cropley was aghast that I would expect something for nothing and suggested we get $5 worth of fuel. I told him he was honourable but stupid and we hadn’t the time. There was silence for a minute or two before I broke it with a compromise. I would pay the garage $1 and clean the windscreen myself to save time. He laughed and asked how it would look on the expenses when all this was over. I got cross and told him they – the bean counters – would just have to take my word for it.

We picked our target, the forecourt was deserted so we rushed in, leaving the braking to the last minute, my door open before we came to a complete stop. But my hope of being able to clean the windscreen before anybody appeared was dashed when a smart young bird appeared. “Fill it up?” she asked as a matter of course, her hand already on the pump.

“No, we just want to clean the windscreen,” the words rushed as I grasped the sponge out of the bucket and gave her $1.

“What? Don’t you even want a dollar’s worth of fuel?”

“No, we don’t have time.”

”This is amazing,” she said as she looked at us suspiciously and slowly asked, “Have you hooked something and this is your getaway car?”

We laughed and denied her charge but she hung on to her dollar and was far from convinced.

The sandwiches are finished and it is time to sleep, not that I have any choice in the matter. My eyes ache, my arms protest and my head pounds as Cropley snuggles back into the seat, knowing he has a long night ahead of him. I ask Cropley his condition before giving in.

“Mate, mate,” he reassures me. “If I was any fitter I’d be dangerous.”

I want to believe him.

There are no notes of that night, I am too weary to care and can do no more than fill out our fuel check chart and hourly speed check. I hover between drowsing and sleep, occasionally asking Cropley if he is still okay but hoping against hope he won’t ask me to drive. The man is inspired and alone for all the help I give him. He is averaging between 145 and 150km/h and does so for more than four hours.

At 2559.6km he comes in for a refuel at the Western Australian border. We pay $55.25 for fuel at 40.4 cents a litre which gives us 6.2 km/l (17.5 mpg). The system says it’s my turn and 12 minutes at a fuel stop has me convinced I can drive my way out of the sleep. I’m even keen to have a turn behind the wheel … it is an Alfa. And for 30 minutes I sit alert while Cropley slumbers beside me and I pretend to be In Charge And On Top.

What nonsense, for my eyes are closing, I am slowing down and my concentration had ceased to exist. One half of my brain says “Just close your eyes and everything will be alright” while the other half cringes in front of the Cropley determination and demands that we drive on. I try singing my way through Evita yet again but my voice trails off and I know I will need to admit defeat to Cropley. He takes it very well, as if he had known all along that I would be the weak link, that for all my demands of a co-driver it was going to be me who let the team down.

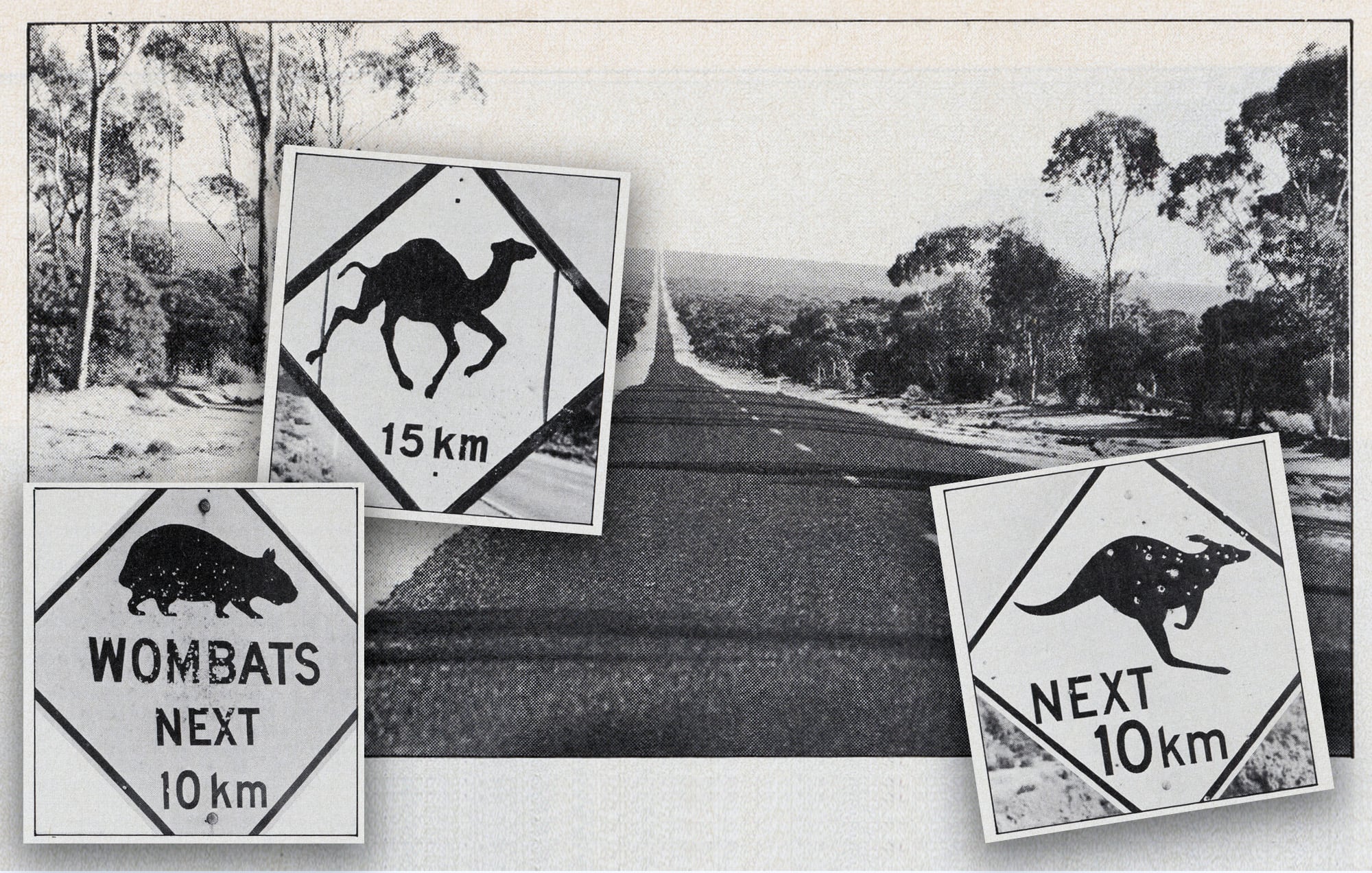

Superman drives on with a forlorn passenger sitting up every so often muttering some cliche about wishing he could do his share and then falling back into the seat to the respite of fantasy. Cropley makes the decision to stop at Balladonia for $15 worth of petrol to ensure we can keep going to Norseman where we take on $31.30 at 38.9 cents a litre after arriving at 3.31 Sydney time. Norseman is 3992 km from Sydney and Cropley has driven across the Nullarbor through the seemingly endless scrub with not a camel or policeman in sight and although he tells me of the ’roos hiding in the bush by the side of the road I don’t see them, so they don’t exist.

We don’t even take a time for the 21st hour but our combined accumulative average speed after 22 hours is 140.8km/h. I try again after Coolgardie and Cropley gets some sleep but now we are on the home stretch and nothing can stop us. Morning is coming and my body’s metabolism wakes up with the day and I let Cropley sleep through the 25th and 26th hourly checks.

My mind begins to argue with itself and spends hours calculating possible arrival times. The smallest, most minute, happening becomes something significant. I count the number of cashews and divide them into the next three hours and work out that each nut has to last me seven minutes. So I begin by sucking one clean of salt and then twirling it around my tongue before nibbling it ever so gently at one end. Despite all my best intentions I find I can’t make them last more than five minutes so I will run out well before the next fuel stop.

I remember dropping a cashew, I’m sure I did, down under the seat. I search for the bloody thing, trying not to disturb Cropley while keeping half an eye on the road and feeling around under the seat among the apple cores and orange peel. But I can’t find it. Rotten cashews, I don’t like them anyway.

Meredin is·our last stop and it’s a back-up for $10 of petrol but still takes five minutes although we don’t bother with a receipt. Perth, if we keep up our present rate will be less than 29 hours from Sydney.

The car is perfect, running beautifully, coping supremely with the road in a smooth, effortless fashion that proves two litres is really capable of achieving all that 4.9 litres could ever do. At least when it is two Alfa litres.

Our confidence is high, too high. Two hours out of Perth, the engine starts to lose power. At first we think it’s the same old problem with the change-over of the petrol tanks but no amount of fiddling from fuel pump to fuel pump makes any difference. It simply won’t pull more than 4500rpm, then it is down to 4000rpm and passing becomes a chore of anticipation, going down to third or even second gear, building up the revs to 4000rpm, changing up and hoping the momentum will carry the car forward and up to 4000rpm again before repeating the action in third and then fourth and, perhaps if the road is flat enough, even fifth. Our average begins to drop but there is no alternative but to continue.

We curse Italians and Alfa Romeos and swear we’ll never do this trip again in a temperamental twin-cam four when there is a bulletproof bent-eight to rely on. Then it is gone as quickly as it came and the Alfa is running cleanly to the redline and I give it everything to prove again and again there is no problem and we will make it. Cropley smiles broadly and admits he would push the car across the line if he had to.

Soon we are into suburban Perth and coping with the country travellers and early workers who clutter up the road and impede our progress. It is going to take more than 29 hours but we know we’ve beaten our record and gone under our aim of 30 hours and, despite his exhaustion Cropley is delighted.

We catch one red light and then another, our seventh, but it is the last before the Swan River bridge and then we have Brian Foley in the Giulietta in our rear vision mirror and we know we are there.

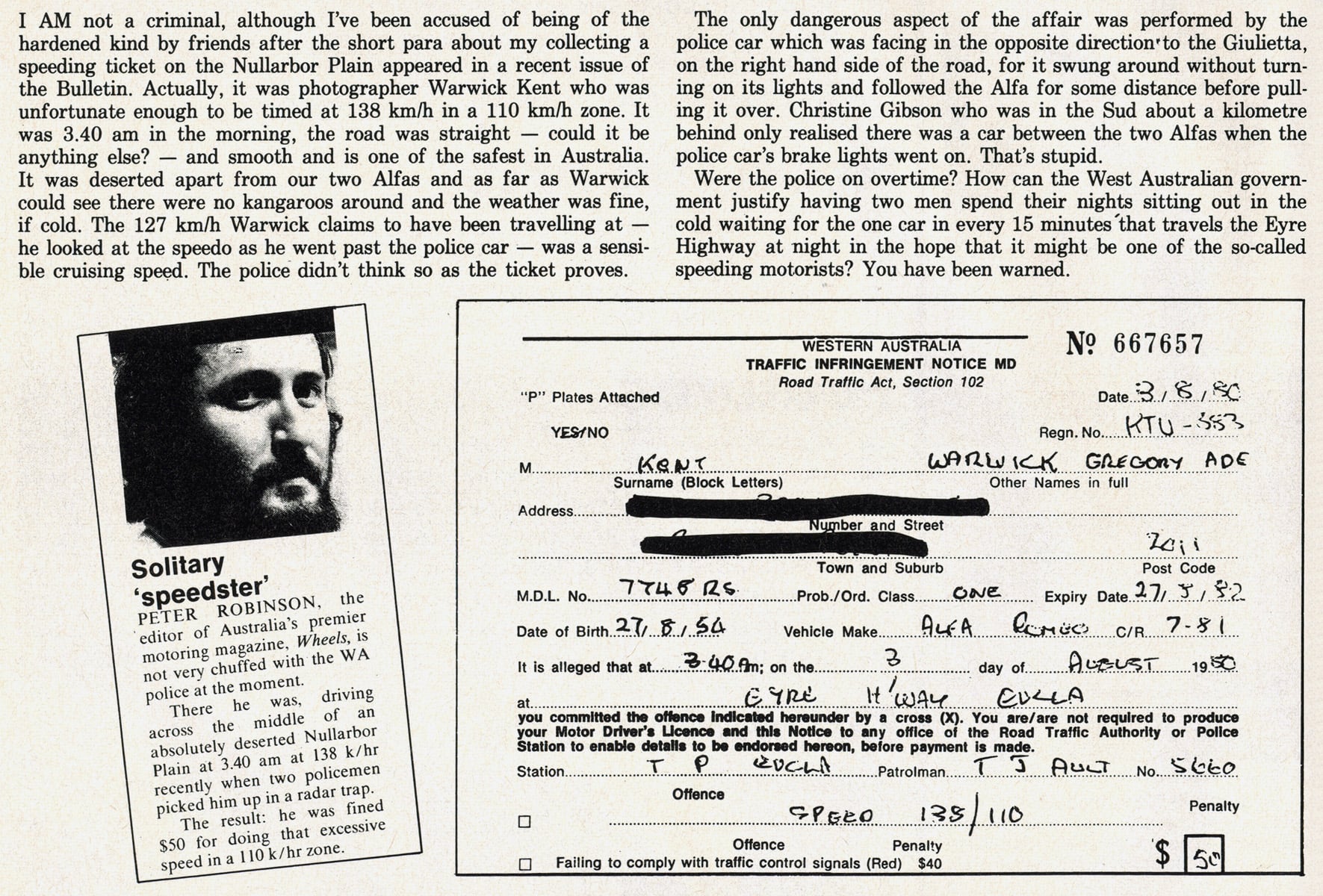

The morning peak hour is disturbed by a proud and boastful toot of the horn as we cross the river after 29 hours 14 minutes and 5 seconds for an average of 137.5km/h – or 85.4mph – and pull over. We stumble out of the car and tell Foley of our late start and dare him to argue with us. But all he wants to know is if we were caught by the police on the Nullarbor like Warwick Kent at 3:40am.

We follow Brian to the motel and I drive into the car park and quite forget the driving lights protrude beyond the bumper bar. They crash hard up against the wall and I sit and laugh and Cropley tries to look disappointed through his desperate tiredness. But he has crossed the continent and done what he left England to do and dismisses it with a “She’ll be right mate, they’ll fix it”. The old Cropley has returned.

We recommend

-

News

News'Cannonball Run' Lamborghini Countach added to National Historic Vehicle Register

Iconic Countach inducted into elite club

-

Features

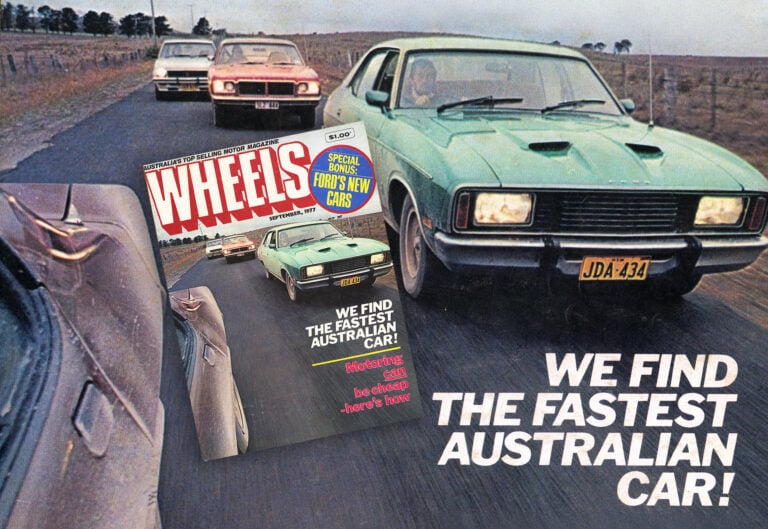

FeaturesFrom the Wheels archives: We find the fastest Australian car

In September 1977, Wheels settled the argument about what is the fastest Australian car once and for all.

-

Advice

Advice10 Australian roads you have to drive

Hitting the open road is the ultimate form of freedom, and we've picked 10 Australian roads you absolutely have to drive