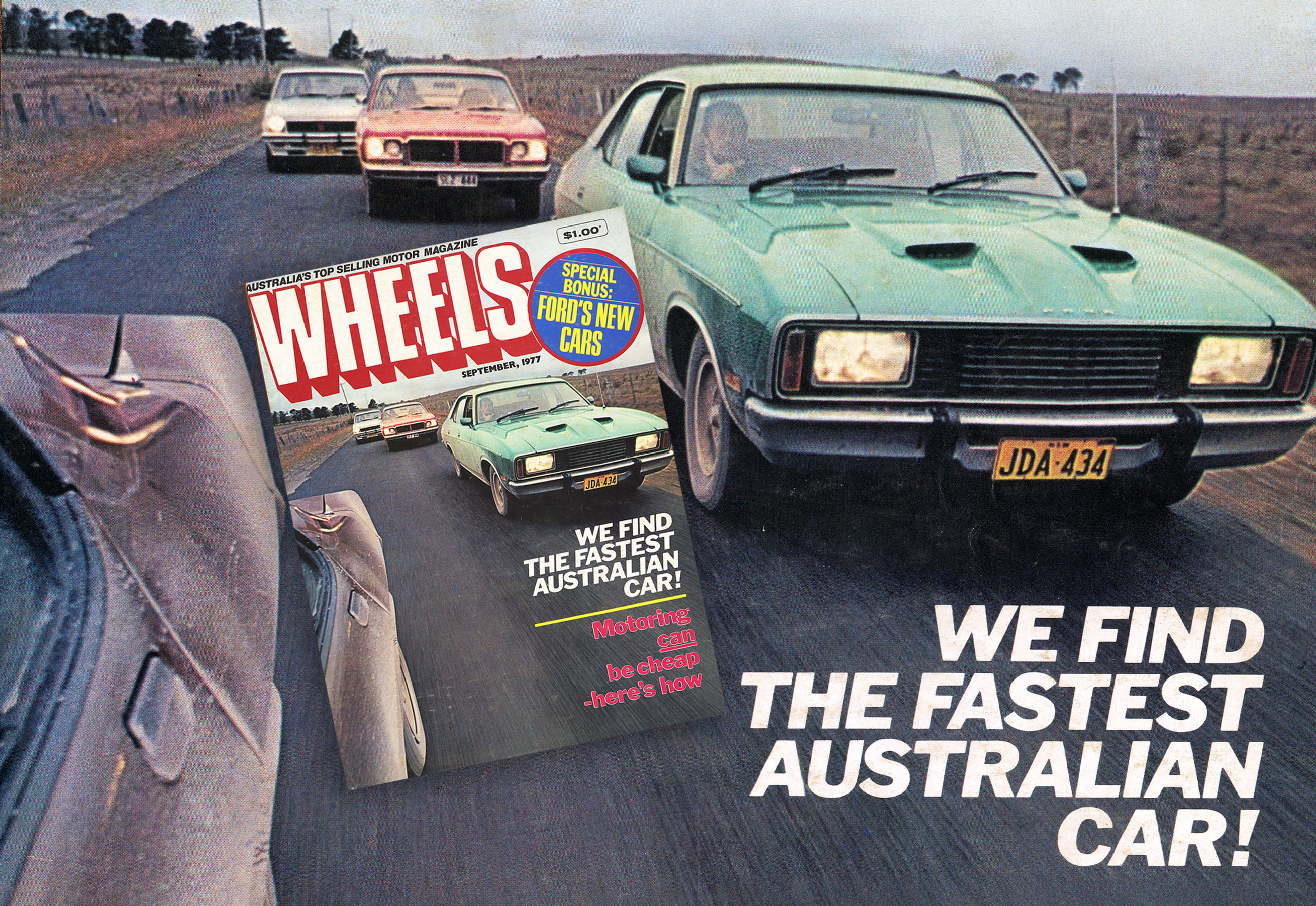

People who drive uneconomical cars are criticised these days. People who drive cars fast aren’t exactly worshipped, either. But we’ve done both, to find out which of these four boomers is the fastest car made in the land of Oz. We did it because YOU wanted to know…

First published in the September 1977 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953. Subscribe here and gain access to 12 issues for $109 plus online access to every Wheels issue since 1953.

To hell with fuel consumption. To hell with styling and boot capacity and warranties and rear knee room. To hell, even, with ride comfort and crash safety. This comparison of the four fastest Australian cars is unashamedly about Power, Speed and Acceleration and there’s no way of getting away from it. And it’s a real change and a pleasure, we can tell you, to be writing about that infamous trio again.

Power, speed and acceleration, you see, are all nouns of 1972 – the words which used to satisfactorily convey the lifting, rocking bonnet, the haze of blue rubber and the pair of compressed eyeballs which resulted when you drove a 1972-style Australian V8 sedan a very long way in a very short time. It was simple, private excitement.

Nowadays the world has discovered its energy problems. It has felt an oil crisis and suspects that a bigger one is coming. It has learned that car exhausts cause the lion’s share of urban air pollution and it has learned that “something has to be done” in a frighteningly short time.

It has learned that cars capable of holding families can be built with small engines (Alfasud,

Golf, Fiesta) and that’s a big development. But the world still builds five, six and seven-litre cars for people who like silence with their kick in the back. And they sell.

People, wastrels though they be, still like V8s. Every carnal car sitting on the beach front has five litres under the fake airscoops. Every executive-driven company car worth its salt packs an eight – sixes are for sales reps – and a lot of us in the rank-and-file enjoy the big donks as well.

So while the situations, financial and legal, exist for people to buy and own V8s and to afford 5 km/I on their way to work and back, V8s will endure. Buyers will option them in, car builders will happily bolt them together, petrol station owners will gleefully fill the tanks. And motoring magazines will test them …

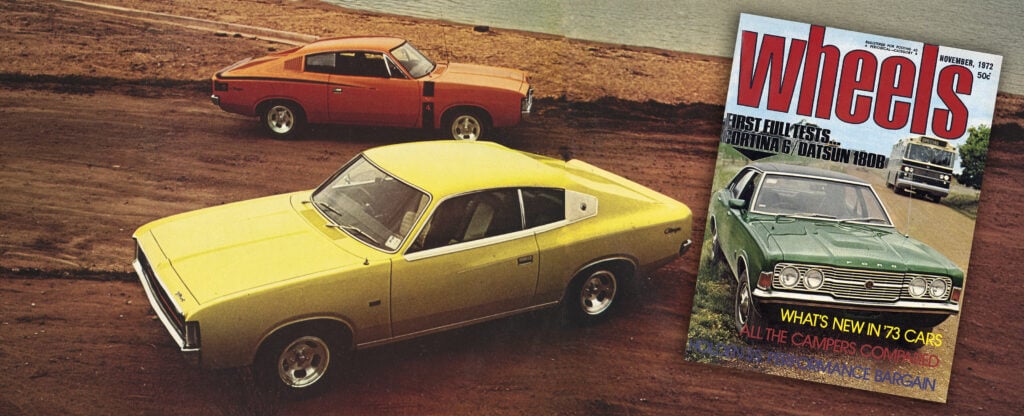

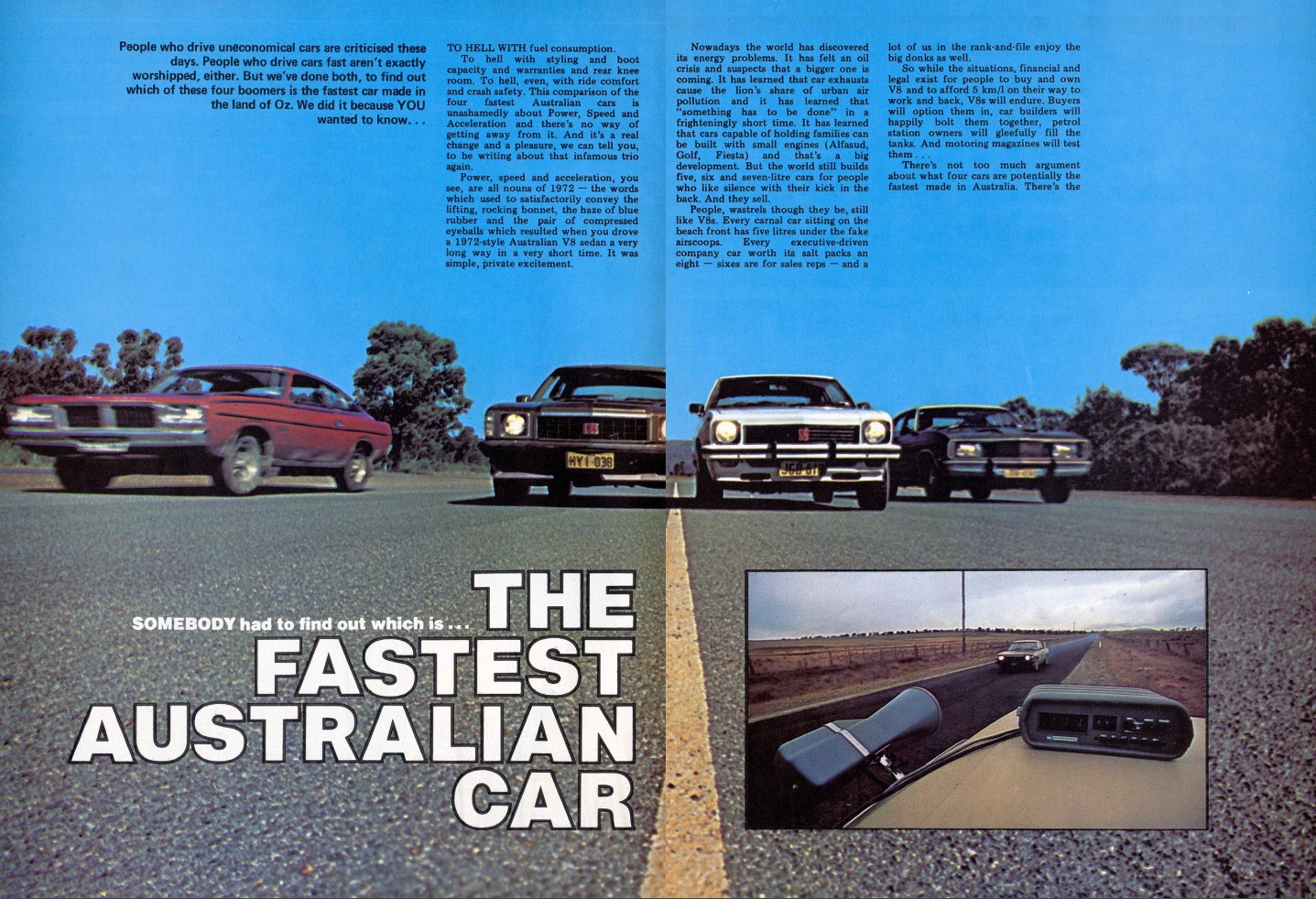

There’s not too much argument about what four cars are potentially the fastest made in Australia. There’s the obvious one – the 5.7 litre Ford Falcon, packing the biggest engine in a local lump. There are two Holdens – the Monaro GTS and Torana which both have the five-litre V8 as their top engine. And there’s a Charger, the lightest of the big Chryslers, but not a 5.3 litre V8. We spoke to Chrysler’s engineers and were assured that if we were prepared to give a 4.3 litre hemi-six Charger long enough to wind up, it would shade a 5.3.

We assembled these cars and as always there were hassles to be coped with and compromises to be made. The biggest compromise was deciding to make do with automatic transmissions in all of the cars. For one thing they make hardly any manual 5 and 5.7 litre V8 cars now and for another (as we were assured by a succession of plausible-sounding experts) at higher engine revs, torque converters in modern slushboxes lock solid so there was “certainly” no slippage and subsequent power loss at top speed.

And for yet another thing, the autos were typical cars – cars like we could actually buy from our friendly local Big Three chiseler. So with management bleating about deadlines, we took the self-shifters.

The Charger was a maroon 265 auto, the same one which Mr Editor Robinson brought back from the CL Chrysler release in Adelaide. Now it had 13,000 kilometres on its odo – most of it at the hands of other road testers but some with more sympathetic drivers (such as Miss Australia candidates and company heavies across from Adelaide) aboard. It was loose in the engine, tight in the body and growled as healthily as ever when you got on the power.

The Falc belonged to “one of the managers” of Ford Sales, Sydney. It was a GXL with air, tape, a hole-in-the-roof and all the other trick bits. It had about 4500 kilometres on the clock and ran like a very quiet Swiss watch. It was reputed to have a dud fuel gauge and demister but the gauge stopped working for a grand total of three seconds in four days and the demister distinguished itself by being one of the finest we’ve ever used.

The Torana was a brand new SS Hatchback built for the Sydney PR fleet and run in by a selfless staff man who spent 1000 kilometres and a weekend looking for a sufficiently flat, straight, deserted and well surfaced piece of road within sensible distance of Sydney for us to time our top speeds in acceptable safety. The Torana had about 2300 kilometres up when we ran it for the clocks – perilously few but as many as we could manage.

The GTS came from a GMH staff member. It had 12,000 kilometres up and distinguished itself from the rest by appearing to have very little in the way of front shocks. But the engine was sweet when you got it to about 2000 rpm – below that, like the Torana, it showed its ADR27 A heritage by belching and running irregularly.

These were the four. We planned to take them out and find out, once and for all, which was the quickest in a straight line under as neutral conditions as we could find – then to take them to the dragstrip and find out about their accelerations and then to make a judgement on which was the fastest Australian car. As it turned out, the decision was quite a lot easier than we’d anticipated.

Top speeds are hard to run accurately – at least the kind which are accurate to fractions of km/h. It’s easy enough to correct a speedo and then to time a car over a known distance and compute its average speed for that distance. That tells most people what they want to know.

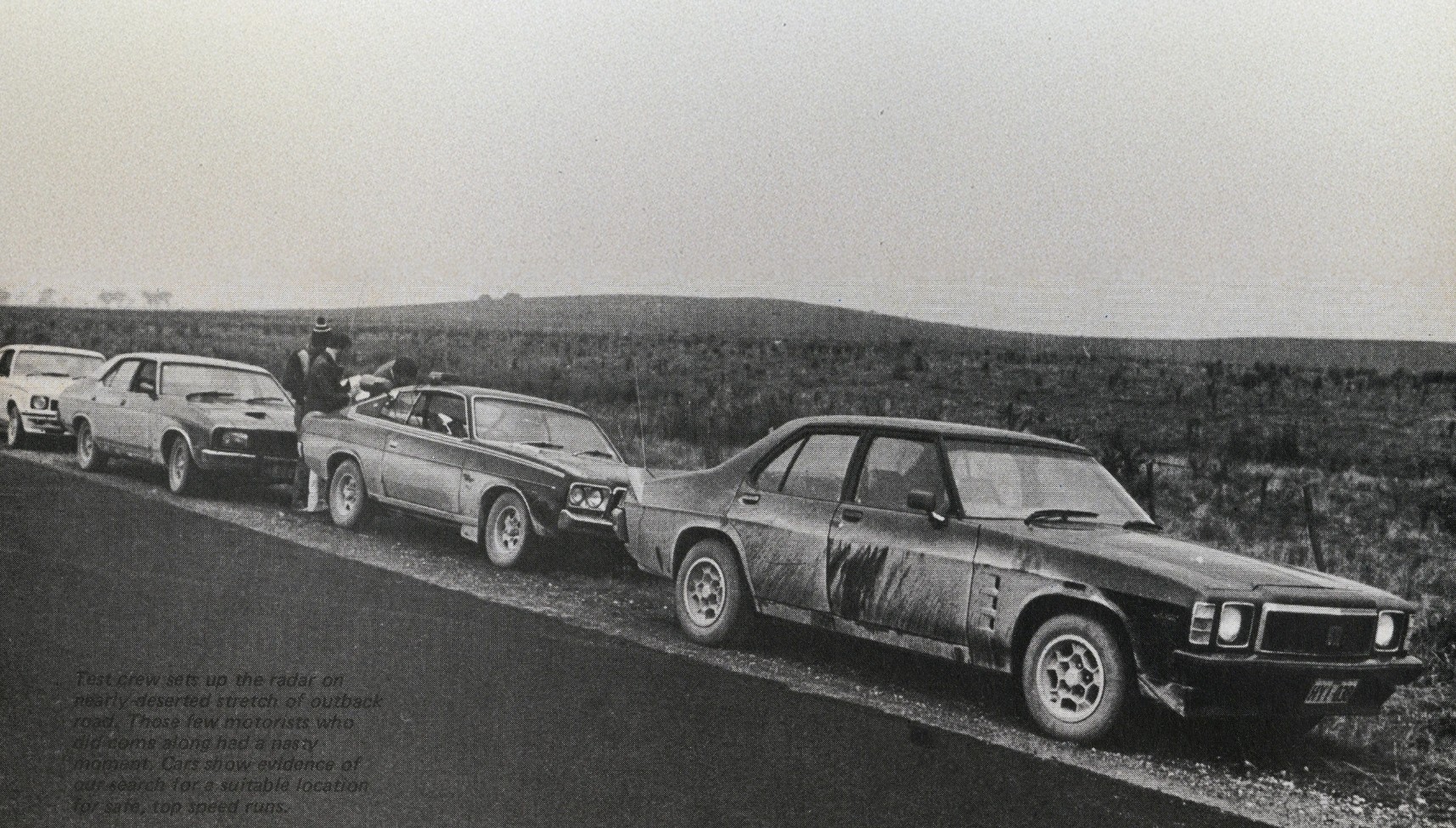

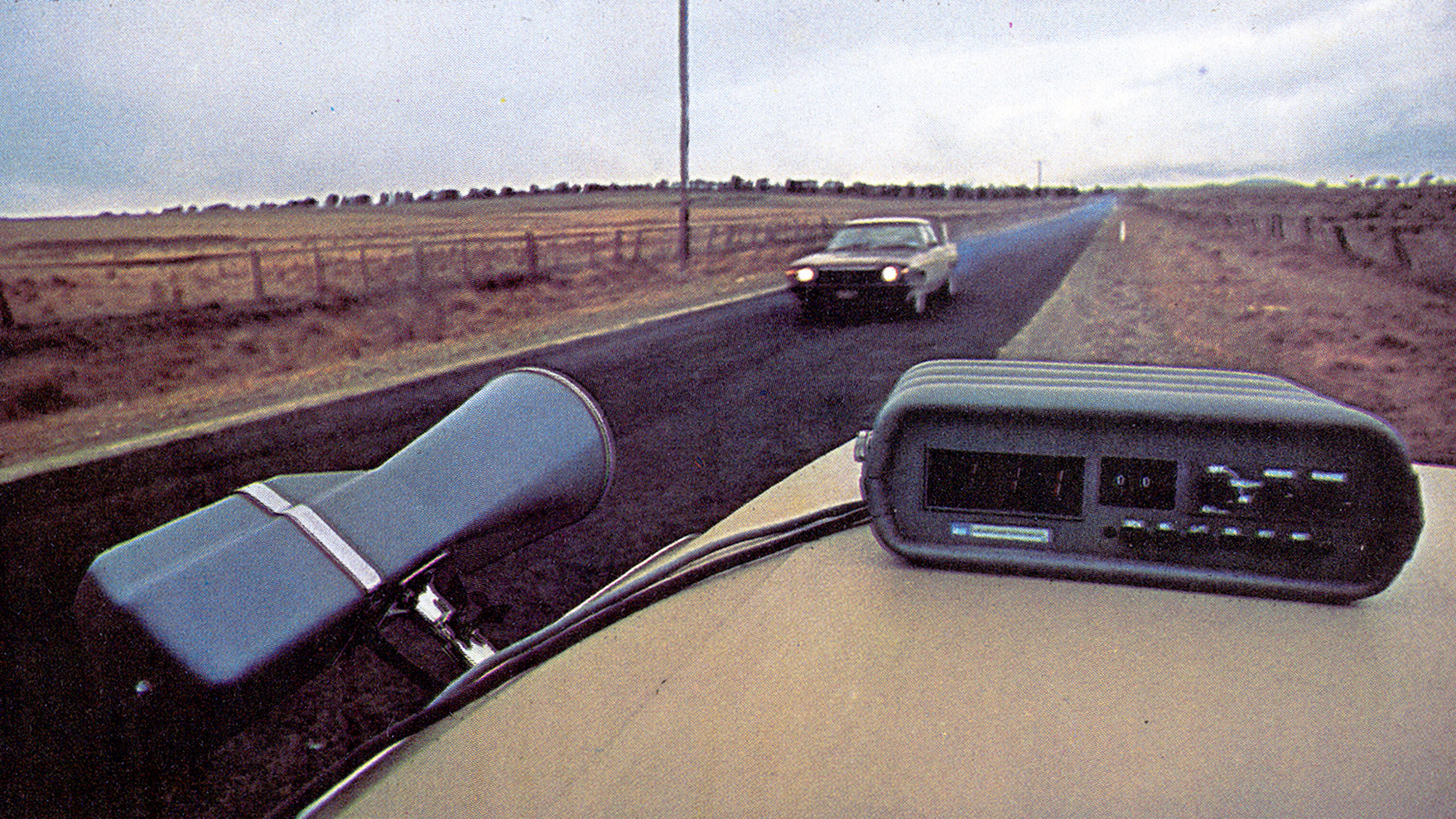

This time we wanted it exact, so we approached a man who is about to start importing radar units for use by Australian police – they’re in the evaluation stage right now – and borrowed a unit to give us dead accuracy.

Our original plan was to set the radar unit up inside each car, beaming down the road and taking readings off the scenery as it flashed past, giving us top speeds. We soon found that approaching cars and the scarcity of substantial fences, rocks and so on on the verges of our piece of straight road put paid to that idea. The radar unit worked okay, but there were fairly long periods where you’d be sitting there with 180-plus on the speedo and the radar readout screen showing a moronic blank. Occasionally it would flash an isolated figure out of the nothingness for a few seconds but there would be no way of knowing if that was the maximum figure or not.

There was nothing for it but to do a police force, set the unit up on the road and drive our four cars through it – and scare the inhabitants of a certain NSW country town half to death.

Our location wasn’t ideal, but we were firm that it was as good as we were going to find this side of the Hay Plain or the Nullarbor. It was a straight, wide piece of road without a centre line, de-restricted, within three miles of the centre of a country town, yet practically deserted. The run-up to the radar straight – about two kilometres long – had a few bends but they could be taken at top speed. There was about four kilometres of wind-up available and a slight slope on the run into our timing straight. As well as that, a fairly fresh breeze was assisting the cars from right three-quarter rear. In short, the cars had just a little help – or at least no hindrances.

The top speed runs

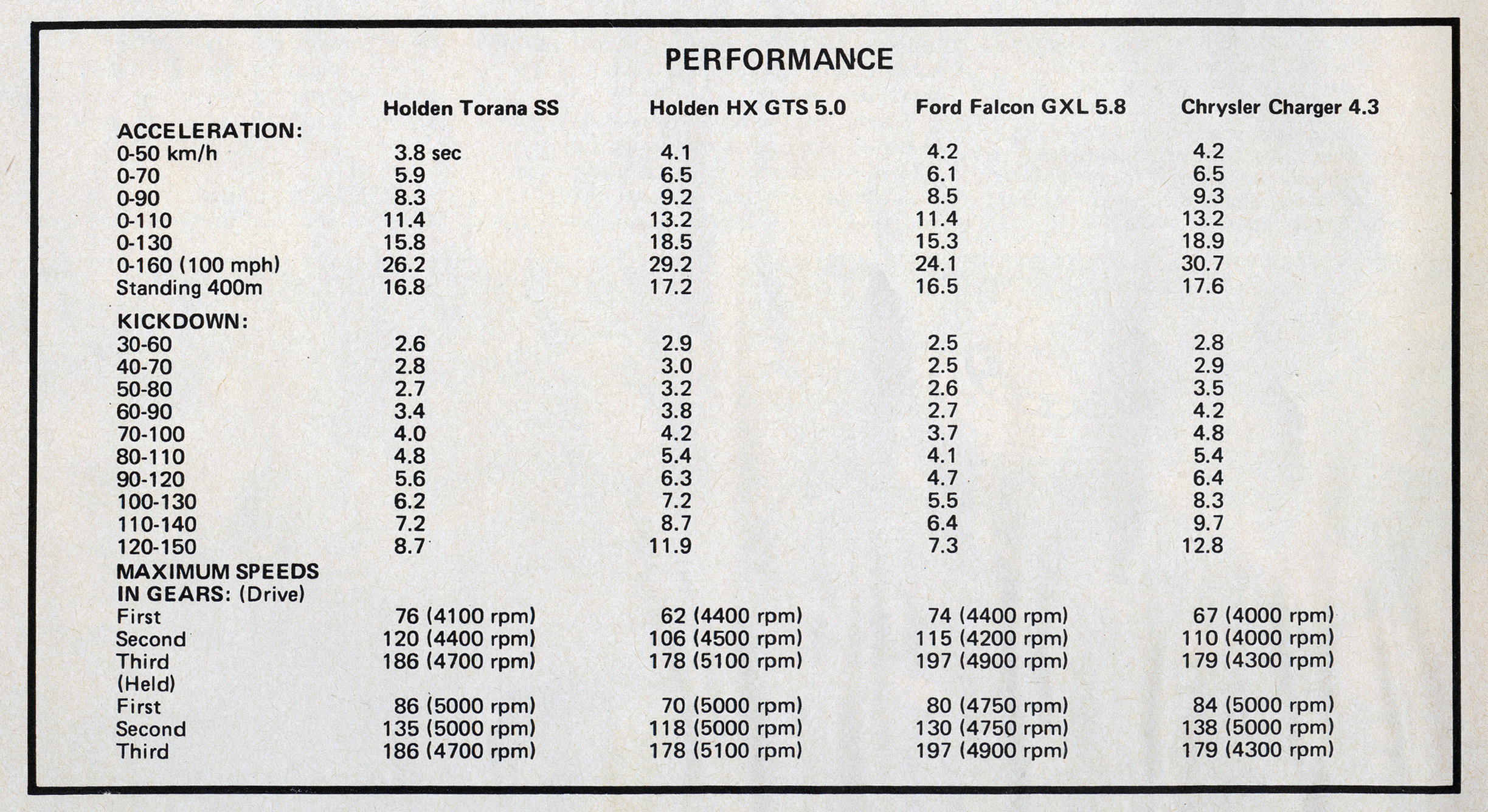

First to run was the Charger, our man deciding to try first what he thought would be the slowest of the four. The Charger appeared over the horizon pulling around 108 (the scale on our US-built radar unit was in miles per hour) and built up to 112 which it held through the trap without wavering.

Repeated twice more, the Charger did exactly the same. It surprised us that the top speed of a car was such a finite quantity – we’d expected to have three different readings, differing by as much as 5 mph (8 km/h). But it didn’t happen. The top speed of the Charger went into the notebook at 179 km/h. Its tacho was dead accurate at 4300, its speedo 8 km/h fast at top speed.

The Torana was also consistent, its three runs sending up 116 each time. That’s 186 km/h. We were quite disappointed in this figure, particularly since the Torana comes standard with a tall 2.78:1 diff and the engine was only pulling about 4700 when it went through our radar trap.

Both the speedo and tach showed themselves to be benders of the facts, since the tach showed 5250 rpm (actually 4700) and the speedo had been way past the 200 km/h mark and off the clock. It was at least 20 km/h fast at top speed. It’s discrepancies like these which cause such folklore to grow up around some cars’ performance levels. There are any number of 130 mph V8 Torana owners about, and these findings won’t do much to dispel the claims. Those guys have seen it on the speedo!

The Holden GTS couldn’t be expected to be as quick as the Torana because of its extra weight and frontal area, though it had a very free engine. It ran consistently at 111 mph – 178km/h – blowing large and ominous clouds out of its twin pipes when the engine turned above about 4500. Its speedo and tach also told fairytales – the speedo brushing 190 km/h (12 km/h too much) and its tach on the 5500 rpm redline (actually 5100 rpm).

And so to the Henry. It had the biggest mill of all and the most weight – 700 cm3 more and around 230 kg extra weight over the Holden. Surely this wouldn’t be the quickest car?

It was· though. It ran through the traps at an untroubled 122 (195 km/h) on its first two runs and our driver had the feeling that it might just go a shade faster. On the third run, wrung out completely, the big Falc turned the clock up to 123 mph (197 km/h) and became clearly the fastest car made in Australia. It also demonstrated that it is one of the more honest, its tacho showing 4800 (4700 actual) and its speedo 204 km/h (7 km/h too many).

There were several interesting factors to come out of the top speed runs. One was the constancy of a car’s top speed. In 12 runs, only one of them changed – and that by 1.6 km/h.

Another was the way in which the Charger and Ford engines coped better with their ADR27 A clean-air equipment (which puts some of each car’s exhaust gas back through the induction system). The Ford and Chrysler were perfectly acceptable – hard to pick, even, from the pre-27 A cars – but the Holdens both ran unevenly below 1800-2000rpm. In a V8, a driver can spend quite a lot of the time below 1800-2000 and as a result there were times when the Holdens were quite unpleasant in traffic. But it has to be said that between 2000 and their effective redline of 5000 (5500 is marked on the tachos) they haul like a pair of locos.

The third interesting factor was the fact that, according to features editor Brian Woodward, who was standing at the timing equipment, each car had a definite “whoosh factor” as it flashed past within a few metres of him. The Charger and the Holdens caused considerable buffeting but the Falcon slipped past without seeming to disturb near as much air. Using this piece of stockman’s logic it is likely that good aerodynamics are the reason for the Falcon’s high top speed – after all, its stated power is almost the same as the Holdens’ and its body weighs more.

At the dragstrip

We expected big things of the Torana here, but we didn’t really get them. The fastest car over the standing 400m course, by a comfortable 0.3 seconds, was the Falcon which turned up 16.5 seconds. That, in Falcon terms, isn’t spectacular because in 1973 auto 351s could be expected to record 16s and a good one might get into the high 15s.

The clean air rules have had an effect on the Falc’s performance. But it still gets from 0-160 km/h (100 mph) in a lively 24.1 sec.

The Torana, for all our attempts at running-in and its top speed runs on the previous day was still suffering from too few kilometres. It turned a disappointing 16.8 for the 400m and made it to 160 km/h in 26.2 sec – 2.1 sec slower than the Falcon. It would improve with age but not enough to be clearly the fastest accelerating Australian production car.

It might equal the Falc, but in our opinion it wouldn’t do much better than that. On the face of it, the General’s five-litre engine is considerably more affected by anti-pollution mods than is the Ford 351 ( or the 302 if our experience with our orange long-term test car is anything

to go by). A good five-litre Torana auto used to be 0.1 or 0.2 seconds quicker than a Falcon over the 400m.

The Charger, with its comparatively small engine and long gearing (as tall as the Falcon’s) couldn’t be expected to turn quick quarters, but it ran out in a creditable 17 .6 seconds – the same time recorded when we tested this car early this year – and it ran to 160 km/h in 30.7 seconds which is a shade slower than the GTS. Before ADR27 A you could expect 17.2-17.3 from this car.

The GTS ran a leisurely 17.2 second quarter and ran to 160 km/h in 29.2 seconds. It had the advantage of a prime, 13,000 kilometre engine, but it was at least 0.7 or 0.8 seconds slower

than it used to be. That performance loss is consistent with the Torana’s and greater than that of either the Charger or the Ford.

Across the ground

Though it is least considered by fast car enthusiasts a car’s ability to go fast in typical road conditions is the most important of the three major yardsticks of performance. After all, you don’t spend much time on flat, straight roads – it took us several days of searching to find one within 200 kilometres of Sydney – and you can’t drive up and down Castlereagh Dragstrip all day either. They’d miss you at work …

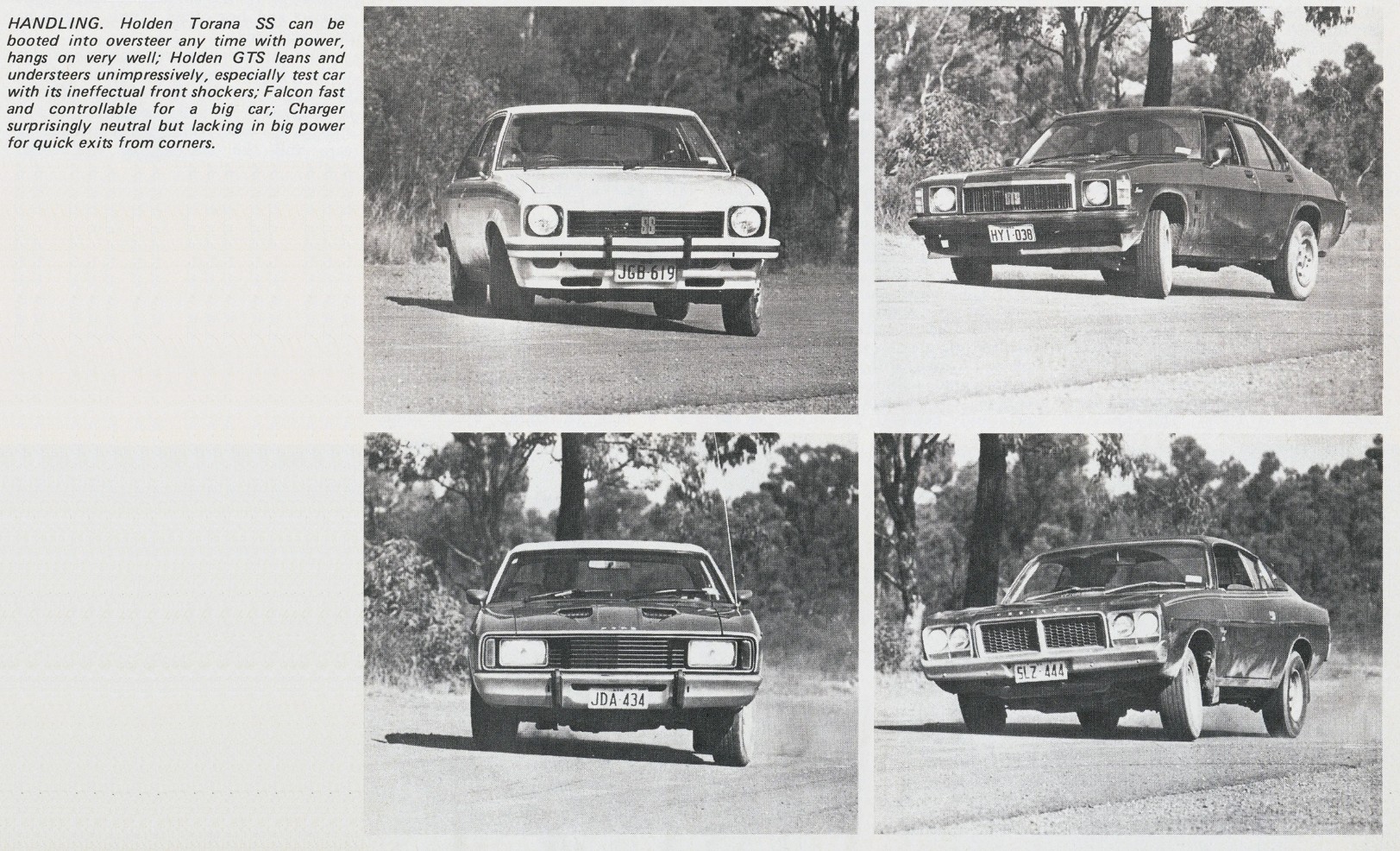

The Falcon and the Torana were clearly the two best at fast cruising on NSW’s array of roads with only a prima facie 80 km/h limit. The GTS was clearly the worst with its over-light power steering, its outmoded front end geometry which caused it to move about on the road a lot, its rear-end steer caused by Sorbent-soft rear suspension bushes, and a pair of clapped front dampers which caused disturbing wallow and lack of precision.

It needs to be said that by the time this magazine is in your perspiring paw there will be a new range of Holden HXs available with the same “radial-tuned suspension” modifications that have turned Toranas from puddings into cars. The car will have better damping, probably a rear anti-roll bar and stiffer shockers. It will be good. At present it’s terrible – even worse than we remember.

The Charger was an honest handling car with its hefty front anti-roll bar and fairly firm suspension settings all round. It went where it was pointed and hung on well, understeering refreshingly little at quite high cornering speeds. But it lacked out-of-the-corner poke compared with the Torana and Falc and it didn’t have a limited slip differential to help get the power down (and help boot out the tail in tight corners). So it was third best. But the Charger did have long touring legs as Mr Editor Robinson has already said in his test of the car (Wheels, Feb). It was pleasant and it was strong. It just wasn’t as quick as the top two.

It is hard to distinguish between the Falcon and the Torana. Once, there was a clear distinction between the Falcon GT and the Torana SL/R 5000 and that was because the Falcon had stiffer “sports handling” suspension and the Torana didn’t have the benefit of the new Opel-inspired grippy front end design. Nowadays the Fairmont GXL (as tested) has softer suspension with a kind of gentle oversteer drift built into it on high speed corners while the Torana has become much better.

It boils down to this. The Torana is probably quicker point-to-point than a GXL Falcon though the margin isn’t exactly big. A Falcon with sports handling suspension would probably hold it on performance while still being out-manoeuvred in tight going because of its sheer body size. It would be an interesting struggle and it would happen at awfully high speeds.

But for comfortable long-distance point-to-pointing the Falcon GXL is undoubtedly best. It is quiet, smooth, soft-riding and still damn quick. The Torana has exhaust booms, jigs on the bumps, stirs up a fair degree of wind noise and goes a bit quicker. But it takes more energy to drive fast and doesn’t have the ultimate top speed.

Our verdict, simply stated, is that the Falcon 5.7 litre is the fastest car in Australia – and if you want to· be sure of it, order yours with the stiffer suspension (and probably a manual gearbox, if they’ll build you one).

One of our staffmen who stood and looked at the top speeds of the fastest cars in Australia (178, 179, 186 and 197 km/h) and the standing 400m times (17.6, 17.2; 16.8 and 16.5 seconds) began reflecting on the good old days of 15 seconds at Castlereagh and 200 km/h on any half-mile straight stretch you cared to name.

“They’ve all had their balls cut orf” he grumbled, his right foot twitching and his burgeoning middle-aged spread receded for a moment as he thought of 1972. And he’s right, of course; they are slower in ’77.

But truly, it’s not too bad. Only against the watches and the radar are the cars really, noticeably slower than they were. Apart from the Holdens’ more obvious ADR effects the four are very similar to the cars of ’72/’73 – but made better in three cases out of four by improvements to their suspensions. And we’d guess that quite a lot of the missing km/h can be restored by some cunning running-in and intelligent tuning.

You CAN still buy a horn car. Each of the four is still fast and powerful. Each of the four can still be owned by anyone on a sensible salary. But whether you SHOULD buy a car like this, knowing that you may well still own it in five oil-tight years’ time, is a matter for much closer consideration than it ever has been before.

We recommend

-

Features

FeaturesAustralia’s 10 Greatest Cars

While it's still sad Australia no longer creates cars from concept to roadgoing, we can at least remember how good they once were. Here's the 10 we think were Australia's greatest ever homegrown cars...

-

Features

FeaturesAustralia’s greatest muscle car of all time

It’s the final countdown as the five winners from each decade face off to see which Aussie Muscle Car is truly the greatest

-

Features

FeaturesRetrospective - The rise of the Aussie classic

A Falcon GT-HO breached seven-figures at auction last weekend, but it’s definitely not the first time prices for classic Australian muscle have gone through the roof

-

Opinion

OpinionMichael Stahl: Cars today are nothing like I imagined they would be 50 years ago

I imagined Jetsons-like creations or the wilder creations of Ferrari and Lamborghini, instead we became obsessed with 'sports utility vehicles'...