You might have heard that the V8 in the new Ford Mustang GT350 and GT350R features a flat-plane crankshaft.

Some of you will nod sagely, others will silently mouth WTF. The concept is actually not too bizarre, but the technology does have a big effect on how engines feel and sound. So let’s start with the basics.

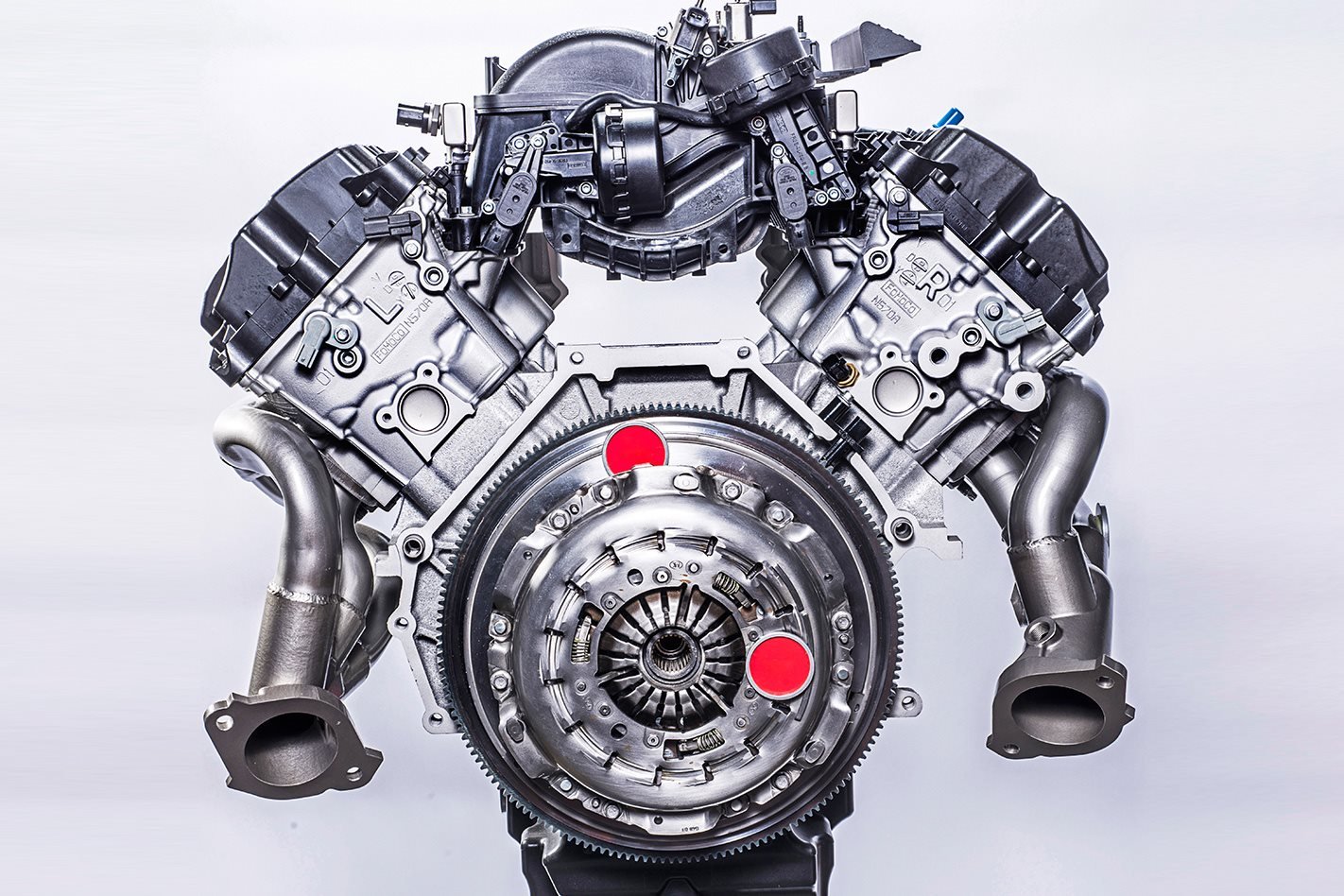

Almost every production V8 engine ever made has a cross-plane crankshaft. That is, if you looked along the length of the crank, you’d see that the big-end journals (where the bottom of the conrod attaches to the crank) are offset at 90 degrees to each other. There are four of them and they visually form a cross shape (hence, cross-plane, depending who you talk to).

With this set-up, you get each bank of four cylinders balancing each other, but an uneven firing pulse on each bank. It’s this unevenness that gives a traditional V8 that rollicking, rhythmic soundtrack.

But a flat-plane crank has all four journals staggered at 180-degrees from each other, so they all line up on a single plane. In this scenario, you get the two banks of cylinders balancing each other, but without the unevenness on each bank. The big clue for bystanders on the footpath is the noise. Unlike the conventional V8 noise, you get a less tuneful note – more like two four-cylinder engines rather than one V8.

So why do it? Essentially, a flat-plane crank will, pound for pound, make more power.

That’s mainly because the different firing order makes for better cylinder scavenging on the exhaust side. Think of it as passive supercharging. And it can do that without complex (and heavy) exhaust systems with cross-over pipes and what-not. Also, the flat-plane crank doesn’t need such big, heavy counterweights to smooth out the engine’s primary vibrations, so it can spin up faster and rev harder.

Flat-plane cranks have been around for a long, long time, mainly in racing applications where the vibes are less important than the outright power of the thing. But some very famous engines have featured a flat-plane crank, including luminaries such as the Cosworth DFV, Ferrari V8s (even road-going ones) and the V8 Lotus Esprit.

It’s not just V8s that can have a flat-plane crank, either. Most four-cylinder donks use a flat-plane crank and so do engines like the boxer four or six as seen in VW Beetles, Suby WRXs and Porsche 911s. The thing is, the inherent vibration in a flat-plane design only starts to show up as capacities rise, so a smaller engine has less to lose in the first place.

Cranking it up

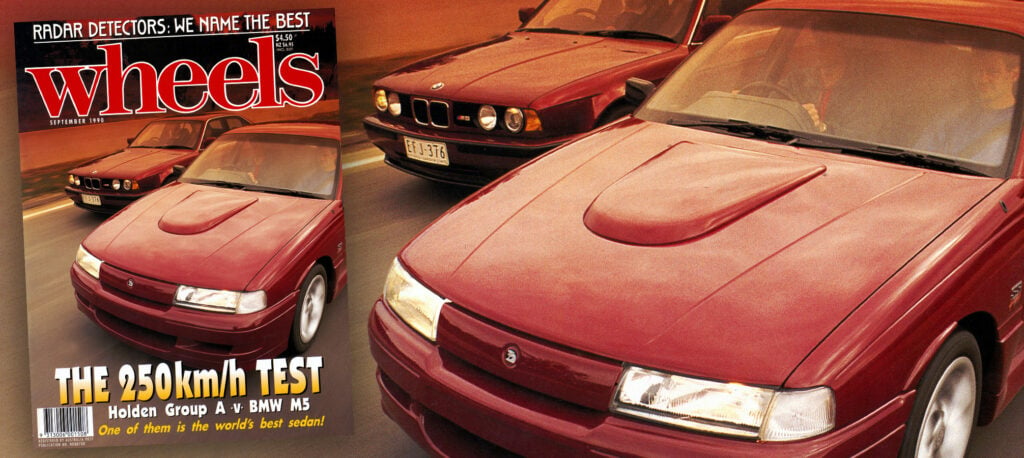

Flat-planes in V8 Supercars

Turns out, since AMG had to reduce the capacity to 5.0 litres (from 6.2) it required a new crankshaft, and there was no development-cost penalty in going for a flat-plane design.

Of course, starting with more or less the V8 from the SLS AMG GT3 racecar, the unit was already dry-sumped. And whaddaya know? When Polestar developed the V8 Supercar engine for the GRM Volvo team, it went for a flat-plane crank, too.

Plane & Simple

Optimising an engine

2 Smaller big-ends Another way to keep an engine compact is to reduce the size of the conrod big-ends. This can mean a smaller crankcase, but it also calls for smaller bearings and, therefore, less bearing surface area. Smaller bearings also means less friction, though.

3 Bent out of shape Some race and motorcycle engines use roller crankshafts which, instead of being cast in one piece, are pressed together in sections using many tonnes of pressure. These allow the use of caged roller bearings for low friction, but they can also become – literally – twisted out of phase.

4 Getting tricky The blueprinting process involves making nth-degree changes to make sure the engine in question is exactly to the specs the designer had in mind. In the case of a crankshaft, this process can include grinding of the big-end journals to align the crank to bring the journals into the precise plane.

5 Staying cross-plane If you do stick with a cross-plane V8, the best way to improve efficiency is to run an exhaust that links the two exhaust manifolds before any collector for improved scavenging. But this is bulky and calls for running super-hot pipework over the top of the motor. Not ideal.