In a bid to reduce emissions and comply with new government-mandated standards, automakers are continuing to embrace a mix of electrification and hybrid technology in their new vehicles.

While electric vehicles (EVs) went through an initial boom period, the lack of charging infrastructure and, in a lot of cases, high purchase price mean sales have softened. They’re also not suited to everybody.

EVs represented just 4.9 per cent of total sales reported to FCAI in March 2025, compared with 9.5 per cent in March 2024. Ahead of the removal of the government’s FBT tax exemption for Plug-in Hybrid Vehicles (PHEV) on April 1, sales rose 380 per cent versus the same period last year as consumers rushed to secure their vehicle.

For many people, hybrids are their way into new car technology: they’re often less expensive to buy and eradicate range anxiety because they aren’t relying on charging.

But what is a hybrid, automotively speaking. In simplest terms it’s combination of both an internal combustion engine (ICE) and an electric motor to provide propulsion. Both Toyota and Honda were the pioneers of hybrid tech in the 1990s with the original Prius and Insight shocking new car buyers with low fuel use. Now there are more different types of hybrids than ever before and it can be tricky to work our which is best for you. Here’s WhichCar‘s guide to the different types of hybrid cars.

Hybrid

By far the most popular type of hybrid is a regular hybrid, sometimes referred to as a ‘series

parallel’ or ‘self-charging’ hybrid. Of the 108,606 vehicles registered in Australia until the end of

March 2025, almost 17,000 of them were hybrids. That number is a 34.8 per cent increase on

this time in 2024.

While they can never be truly zero emissions vehicles – unlike an EV or PHEV – they can cut your fuel bill significantly and only add up to $5000 to the purchase price of the car.

Combining a petrol engine and an electric motor to provide propulsion and increase fuel efficiency

and performance, hybrid models are expanding thanks to their efficiency. As an example, the Toyota RAV4’s claimed 4.7L/100km combined fuel consumption rating is excellent for a mid-size SUV and thanks to the clever tech, easy to achieve in the real world.

So hybrid buyers benefit from less fuel use, less emissions being pumped into the air and less pain

to their wallet, but they also benefit from not suffering from the range anxiety that EV owners can

be familiar with as they don’t need to be charged. What adds to the battery? Well, it depends on

the manufacturer but generally either regenerative braking or – depending on the environment – the

engine.

The regenerative braking process sees a hybrid vehicle convert the energy created by deceleration into electrical energy which is then used to recharge the battery. The engine can also supply the battery with power while in motion or idling as part of the vehicle’s self-charging capacity.

Once the battery gets full enough, it will then power the electric motor – and depending on the

speed and throttle load, that could be able to power the car by itself. Most hybrids let the electric

motor do the heavy lifting setting off from a start, which is where engines can be at their least

efficient. Once at speed, then the petrol engine kicks in to assist. While it seems like a complicated

process, the fuel efficiency results speak for themselves.

Popular examples: Toyota RAV4, Hyundai Kona, MG ZS Hybrid+, Toyota Camry

Mild hybrid

Mild hybrids (MHEVs), as their name suggests, offer a moderated version of the regular hybrid set-up. Most MHEV systems act like an extended start-stop system and can’t actually power the car alone, but are able to switch the engine off when coasting or braking for added fuel efficiency. This means that their fuel savings are significantly less than a regular hybrid. In addition, however, the jump in price from a regular ICE car up to a mild hybrid is significantly less than the increase to a hybrid. Expect more MHEVs to be offered locally as car makers look to comply further with incoming New Vehicle Efficiency Standard (NVES) emissions targets, when every gram of CO2 shaved will help.

Popular examples: Hyundai i30 N Line hatchback, Mazda CX-60, BMW X3

Range-extender hybrid

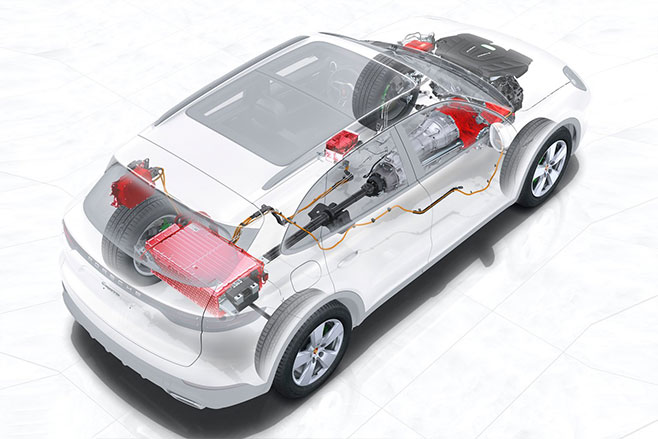

A range-extender hybrid is a hybrid which uses a combustion engine as a generator to power the electric motor. This set-up has no mechanical link to the wheels, and can be a plug-in hybrid like the BMW i3 REx and Leapmotor C10 REEV. However, Nissan’s e-Power hybrid system can also be considered a range-extender as it uses its engine to power only the electric motor, which then powers the wheels.

While the Nissan e-Powers aren’t quite as efficient as their Toyota rivals – 6.1L/100km for an X-Trail

versus 4.8L/100km for an AWD RAV4 hybrid – they are smoother to drive because the wheels

aren’t powered by different sources: the electric motor always drives them.

Popular examples: Nissan X-Trail e-Power, BMW i3 REx, Leapmotor C10 REEV

Plug-in hybrid

Plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) are often seen as the best stepping stone to electric vehicle purchasing

thanks to their potential for zero emissions motoring. Using a larger battery than a normal hybrid, a

PHEV will – depending on the battery size – give owners at least 40-50km of electric driving. Newer PHEVs like the Haval H6GT PHEV and incoming Skoda Kodiaq provide over 100km of EV

driving ability.

So while PHEVs do need to be charged from the grid, they also eliminate range anxiety because

once the battery is depleted, the ICE engine kicks in and it runs as a hybrid – albeit less efficiently

because of the battery’s extra weight. In fact, some PHEVs can be less efficient than regular ICE

cars in the real world if they aren’t charged.

Popular examples: Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, BYD Sealion 6, BMW 330e