Every racing driver in the world, in any category, watches Formula One and thinks, “I wonder what the car that’s winning the championship must be like to drive?” All of them would want to know just how good the best F1 car on the planet is.

F1 has been the pinnacle of our sport for 70 years, and the fact that only a handful of drivers today get to race a top car capable of winning races makes for a lot of jealous racing drivers around the world.

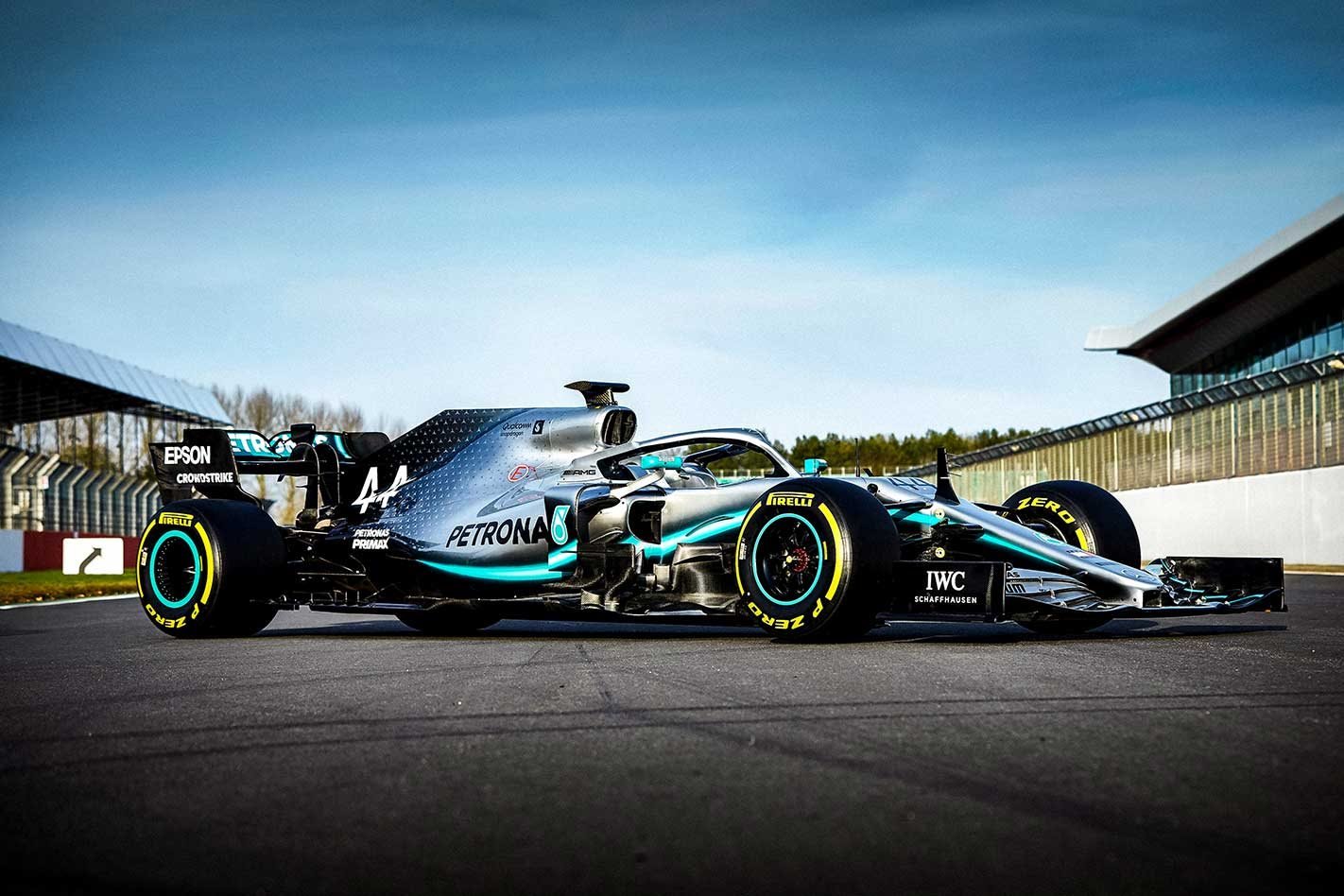

So you can understand my utter surprise when the phone rang late last year to ask if I’d be up for driving a 2019 Mercedes. “What – a current car? You mean this year’s car? Not some demo hack that’s been put together to do doughnuts in?” Yep, Mercedes was offering me the amazing opportunity to drive the very W10 that would be competing in the final races of the season.

Now, I’ve got to give a lot of credit to the Mercedes F1 team. It is in the middle of an extraordinary run of success that started in 2014. It doesn’t really need the publicity of inviting someone other than their existing drivers into the cockpit.

But, amazingly, the team was completely open to the idea of letting me – someone who has never driven one of its cars before – have a go and experience what Lewis Hamilton and Valtteri Bottas had at their disposal to deliver an incredible sixth consecutive drivers’/constructors’ world championship double for the team in 2019.

Considering this was one of the racecars and not just an old one used for show runs, I felt a real sense of responsibility to drive it properly and fast enough to experience it, but also give it back in one piece. Having the Hamilton fan club hurling abuse at me for damaging his car mid-championship was not something I looked forward to, let alone an awkward conversation with team boss Toto Wolff.

Fortunately for me, despite the fact that I don’t have a full driving program this year, I’ve kept up a reasonable level of fitness. I did some panic-induced neck training for the three weeks between the phone call and the day at Silverstone though, because I learned early in my career that being unfit doesn’t only affect your performance, it also means you can’t really enjoy the experience of driving as much.

The team at Brackley was very good at preparing me. Despite the fact that for them it was a filming day and should essentially have been a bit of a jolly, everyone took it very professionally. My seat fitting turned out to be a fairly straightforward process thanks to a mix and match of Valtteri’s seat, Lewis’s steering wheel and steering column, and test driver Esteban Ocon’s pedals. Easy peasy! I then had a session with the engineers, running through the controls on the steering wheel and getting the chance to look through all the options in terms of the power unit, brakes and differential, as well as the reliability side in case we had an issue on track.

What came across was the attention to detail they put in. Yes, the team has nearly 1000 full-time staff and therefore can throw people at problem-solving, but the reality is they have to still think of the possible areas to gain performance, think of a way to implement a tool to gain that performance and then execute it in a way so that the driver can actually gain that lap time on track.

Every phase of the weekend is studied and solutions offered to find a bit of performance. Things such as how to get the brakes and tyres to the right temperature, how to find an extra couple of metres on the brakes when coming into a pitstop, how to get the pitlane speed limiter running as smoothly as possible without any oscillations, how to battle the dreaded tyre degradation by getting the electronic brake balance optimised for every phase of braking and also for every level of grip the tyre offers. The list is endless, but just a couple of hours spent talking to the engineers gives you an idea of how the mindset of the operation is tuned to search for these marginal gains.

It was off to the simulator next to get an idea of what the car would be like on track and also to practise some of the procedures and changing the settings on the steering wheel. After driving the ‘sim’, I found it hard to believe that the real car would be that quick, to be honest. I spoke with Anthony Davidson, who does a reasonable amount of sim work at Mercedes, and he said he thought the same thing, but the data pretty much matches up. Now I was properly excited!

The most recent F1 car I had driven was the 2017 Williams. It was a decent midfield machine that season, allowing the team to run regularly in the points and finish fifth in the championship. Crucially, it had the Mercedes hybrid power unit, so at least I had some experience of that.

As dawn broke over Silverstone, I was totally relieved that the weather gods had been kind to me. It was cloudy, but there wasn’t much wind and it was going to stay dry. The International Circuit is about half the distance of the full Grand Prix circuit, but would still give me a chance to experience the car in fast corners like Abbey and Stowe, as well as medium and slower-speed corners such as Club and Village.

Mercedes had put together a program for me within the mileage limit that the F1 rules allow, which meant I could do a couple of short runs just to dial myself in, then also experience a longer run with a full fuel load and a short run with low fuel at the end. This would give me a really good overall picture of what the car was like in different configurations as well as give me enough laps to have a play with some of the tools in the cockpit to help to tune the balance.

I was certainly a bit nervous before getting into the car, but as the call was made to take off the tyre blankets and release the car, the TV presenter part of my brain got turned off and the racing driver part was activated. The nervousness disappeared, replaced by total curiosity and excitement because I knew that I was going to be driving something special.

As I dialled myself in, the first thing that struck me was just how good the traction and power delivery was. With around 1000 horsepower on tap, you would imagine that controlling the wheelspin is one of the biggest challenges, and I certainly treated the loud pedal with a degree of caution on the first couple of laps. But very quickly I realised that the rear actually stays very planted when accelerating out of corners and I could commit to the throttle much more than expected.

The amount of power itself doesn’t feel like it has changed a great deal since 2017, but the driveability and user-friendliness of the torque curve combined with the ability of the chassis to squat and deliver the power to the road without breaking traction was very impressive. In this current era of F1, where managing the rear tyres during a GP is vitally important, this is particularly handy for the drivers.

The two regular drivers have different throttle-pedal springs that adjust the level of stiffness, but that’s purely a driver comfort thing. What’s crucial is to make sure they have the right amount of control with that pedal to deliver the torque demand when coming out of a corner and balance the wheelspin. The suspension design and rear aero package clearly work well in terms of offering the grip needed, and that is a really crucial aid for Mercedes on a Sunday.

I expected the W10 to be impressive in the high-speed corners and of course it was. As I started to lean on the car on the corner entries, I soon realised I was so far behind the limit it was almost laughable. With every lap I started carrying more and more speed in and the only limiting factor seemed to be the tyres, which started to grain even within the first five laps. We had planned to swap back and forth between a couple of sets of tyres to try and eke out the mileage on them and that allowed me to build up speed in the faster corners.

The grip level was as staggering as I expected it to be, though experiencing it first-hand was something very special. As one of my heroes, Mario Andretti, would say, it feels like it’s painted to the road. My last-minute neck training felt useless as the g-forces built up, but I was loving every second of it. With every lap I was charging through Stowe faster and faster.

What’s interesting is how you can feel the downforce and resultant drag in the first two flat-out corners. As soon as you wind on the steering lock, the drag really kicks in and you can clearly feel the rate of acceleration reducing. Downforce really is a driver’s best friend and at probably 80 per cent of the circuits on the F1 calendar you would gladly take the penalty of drag for having more downforce.

Brilliant as the W10 was in the high-speed corners, it was the performance in the medium and slow corners that surprised me. All season long rivals such as Ferrari talked about how good the Mercedes seems to be on entry to these types of corners and now I fully understand why.

As I got braver and braver on the brakes into Village, I was blown away by just how deep I could brake and also how much I could trail the brakes into the apex. One of the trickiest things in the Pirelli era since 2011 has been the ability to load the front tyre with both braking and steering load, but Mercedes seems to have nailed that with the W10. You can really pitch the car and turn in to the apex of the corner on the nose, and the most impressive part is that the rear of the car doesn’t feel like it’s going to lose any stability.

The combination of the level of downforce, aero balance, the brake migration maps (where the balance is adjusted between the front and rear through the entire braking phase) and the electronic differential work in conjunction to give the drivers the ability to really attack those corner entries. That first phase, when you hit the brakes and start to turn the wheel, is so important. It sends the messages of how much grip the car has to your brain and you then adjust the speed and steering lock accordingly until the apex before picking up the throttle.

Having a car that’s confidence-inducing is very important in any category of motorsport, and the W10 is certainly that. The fact that even someone like me, who hasn’t really driven a modern F1 car in two years, can feel confident to attack the entries at corners such as Stowe or on the brakes into Village within a handful of laps is a sign of a great car. It doesn’t do anything unpredictable and that’s one of the big reasons why, across the 21 races of the season, the Mercedes has been a competitive package.

It was really interesting to load the car with 110kg of fuel and see just what it would be like for the drivers at the start of a GP. The team did its usual adjustments in terms of aero balance for me to really experience it properly. Of course you can feel the extra weight of the fuel, but that’s no different to when I raced in F1 or in any other category. The change of direction gets lazier and everything just happens slower – braking, accelerating and cornering speeds.

What surprised me was how much the extra weight affected the tyres in terms of graining. All through the season we heard drivers talking about having to manage and control their pace, particularly in the first stint of the race with a full tank of fuel. Perhaps the biggest example was at the 23-turn Singapore circuit, where the race pace was at times an astonishing 13 seconds slower than the qualifying pace.

It’s a pretty frustrating way to drive a racecar to be honest. As soon as you feel the front start to slide a little bit on the corner entries, you need to slow down because that graining is just going to get worse and worse; similarly, as soon as you get a little bit of wheelspin on the rear you know you’re on a slippery slope.

This is why the drivers all have to drive so far below their limits on a Sunday and also why we rarely see them look exhausted after a race. These supremely fit athletes are not being physically tested, but instead their minds and senses are on high alert for any form of extra energy being put into their tyres.

Weight is an interesting point because the 2019 cars weigh 743kg, which is 138kg more than in 2004. Yes, the W10 is unbelievably quick, but it has so much downforce and weight that you don’t feel it as a brutal, violent beast in the way the V10 cars from the mid-2000s were.

I’ve been lucky enough to test Juan Pablo Montoya’s 2004 Williams-BMW and that was an incredibly brutal experience that had me on edge the entire time. The extra weight we have now not only adds about five seconds of lap time but also has a major effect on tyre wear and graining, so I do have some sympathy for Pirelli in that respect.

What’s good about the W10 is that, in whatever condition, the car is balanced and predictable. This means that Lewis and Valtteri can adjust their speed to the level of grip offered by the tyres and for the weight without the car having any unusual shift in balance. The downforce, braking stability and amazing traction mean they can often manage their tyres better than others on the grid, and this means that even on weekends where they may not have had the fastest car during qualifying, they can keep the pressure up on their rivals during the races and capitalise.

My day at Silverstone was a truly memorable one. I’ve been very lucky to drive some incredibly special pieces of F1 history over the years; the W10 is the seventh different championship-winning F1 car that I’ve been privileged enough to drive.

For me, the Nigel Mansell Williams FW14B from 1992 was emotionally the most special car I’ve driven, the 2004 Williams FW26 was the one that attacked my senses the most, and the 2011 Red Bull RB7 was the most responsive and sharp. But perhaps it’s the very nature of the sport that, with evolution and knowledge gained, the cars get better and better; overall I’ve got to say that the 2019 Mercedes W10 is the best racecar I have ever driven.

MERCEDES-AMG F1 W10 EQ POWER+ SPECS Engine: 1.6-litre V6, DOHC, 24v, turbo, hybrid Power: 750kW @ 15,000rpm (est) Weight: 743kg 0-100km/h: 2.0sec (est) L/W/h: 5000/2000/950mm Tracks: 1583/1567mm (f/r) Price: $250 million (estimate; includes 21 international track days)

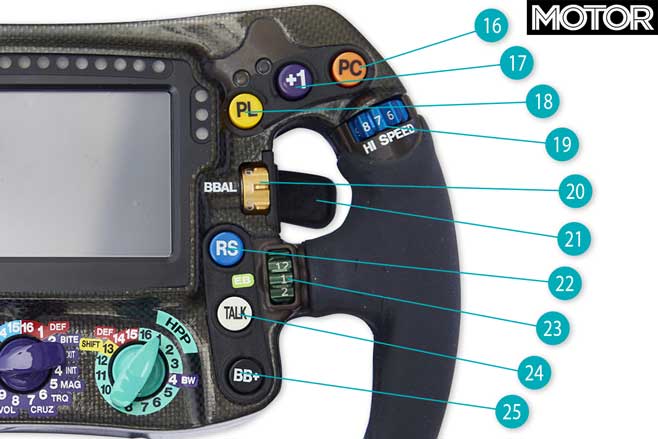

Formula One Steering Wheel Explained

An F1 steering is a complex piece of engineering that controls countless functions on the car and is worth about $100,000. Lewis Hamilton’s wheel has 25 dials, buttons and paddles on the front alone, set around a digital dash display panel, and this is what they all do.

01 | DRS Operates the Drag Reduction System, which opens the slot gap in the rear wing to increase speed and make it easier to overtake a car ahead.

02 | Skip (10 preset) Increases the value of a selected parameter by 10 preset units.

03 | Gearbox Neutral Only selectable via this button to prevent unwanted on-track selection of neutral via the gearshift paddles.

04 | Differential 2 Specific diff setting adjustment for corner entry.

05 | Engine Braking BMIG (braking migration) adjusts how much engine braking applies.

06 | Downshift paddle For, er, changing down gears.

07 | Mark Used to identify a point of interest in the data as indicated by the driver.

08 | Differential 1 One of four dials used for diff adjustment, altering torque transfer between the rear wheels.

09 | Accept Used to accept the default modes selected by the Skip 10 and 1 buttons.

10 | Brake Balance Rearward Allows the driver to move the brake distribution rearward 0.5 per cent.

11 | Track Warnings These light up in different colours (yellow, blue, green, red, etc) according to warnings from track marshals and race control.

12 | Shift Indicator LED lights running from left to right, indicating when the driver needs to change up a gear.

13 | Strat Rotary How often have we heard ‘Bonno’ give Lewis a new Strat setting? These are the primary Power Unit modes.

14 | Menu Rotary Controls all the chassis settings, from radio volume and dash brightness to data display menus and rain settings.

15 | HPP Rotary Used to control the numerous High Performance Powertrain (HPP) settings, including for MGU-K energy recovery, as advised by the pits.

16 | Pit Confirm Sends an alert to the garage so the crew knows the driver is coming in, whether unexpectedly or by request.

17 | SKIP +1 preset Increases the value of a selected parameter by one preset unit.

18 | Pit Lane PL sets car to the pit lane speed limit.

19 | Differential 3 Specific diff setting adjustment for high-speed corners.

20 | Brake Balance Changes the balance to the front or rear, in bigger steps than with the BB- or BB+ buttons; used for different corners on qualifying laps, in the race as the fuel load reduces, or to reduce brake temperatures.

21 | Upshift Paddle New cog.

22 | Race Start Prepares the car for a race start, deploying maximum power.

23 | Differential 4 Specific mid-corner diff adjustment.

24 | Talk Radio button to enable the driver to talk to his engineers in the pits.

25 | Brake Balance Forward Allows the driver to move the brake distribution forward 0.5 per cent.