The other day the worst possible thing happened – I reversed into the wall at the back of my garage in my beloved 1986 Toyota AE86 Sprinter.

A silly thing to do, yes. Flustered and in a bit of a rush, I edged backwards with my eyes glued to the rear vision mirror, glancing to the left and right side mirrors to avoid, ironically, disaster. A very tight space, but I was reasonably confident in my sense of where the back of the car ended, and the wall started. I was wrong.

Fortunately, it was just a mere light, low-speed kiss, the plasterboard of the wall coming off very second-best to the plastic bumper of the 39-year-old Toyota (which, miraculously, had no damage at all, not even the slightest mark). But it was still enough to cause much stern self-consternation.

Sheepishly, it’s occurred to me that I’ve become very used to the reversing cameras, sensors and even the cosseting knowledge of reverse autonomous emergency braking of the latest modern cars. A little too used to them.

I think I’m far from alone. And is there a risk of becoming too dependent on modern driver aids, to the point you’re not just a chance at reversing an old car into a garage wall – but of making a bigger mistake out on the public road?

For a while now, modern cars have given their drivers a heightened sense of invincibility. They’re quiet, well-insulated from the outside world – five-star-safety cocoons of airbags and passive safety equipment. But semi-autonomous driver aids have taken this to another level.

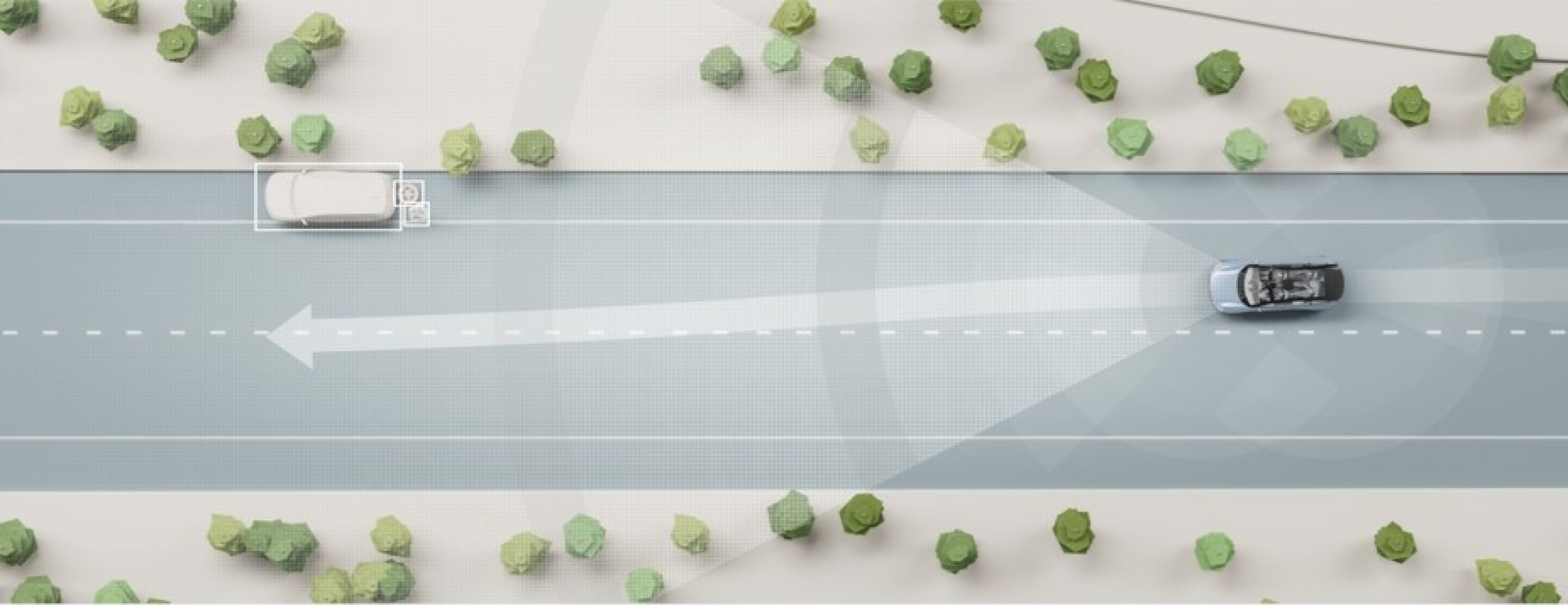

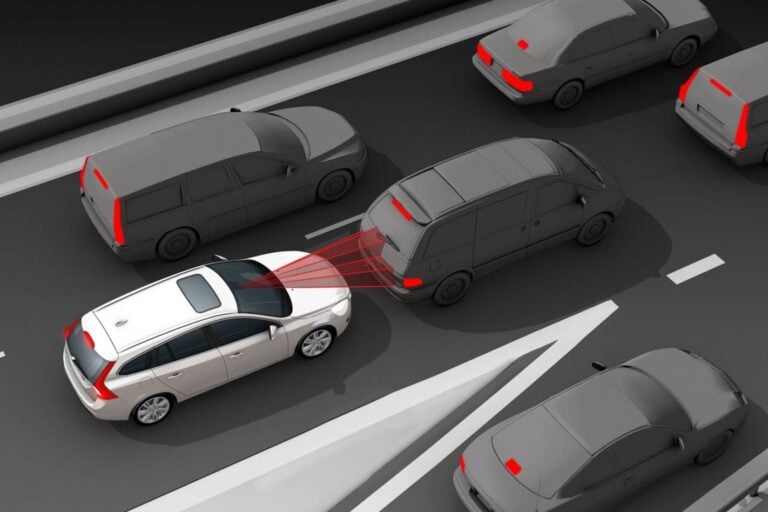

The best new cars wrap you in several layers of computer-controlled physical assistance, from emergency autonomous braking (AEB, in forward and reverse, and even at junctions) to active lane-keeping, blind-spot monitoring (some systems with steering intervention) and radar cruise control that can brake the car to a stop.

The efficacy of these systems, particularly active lane-keeping, varies hugely between manufacturers, and many are so bad you have no choice but to turn them off. In some respects, these might be the safest systems of all.

But some of them are so good that after a while you’re a bit too tempted to leave them on – especially if turning them off requires digging through several menus every time you start the car. The best active lane-keeping systems you can feel subtly driving the car for you, beneath your grip on the steering wheel. That’s as your mind enjoys the newfound extra capacity to wonder what to make for dinner.

Should the worst happen, and very suddenly, the driver, over-dependent on a feature like this, almost needs waking up from the semi-lucid state their modern car has lulled them into. It’s no wonder we now need driver attention monitors to make sure our eyes are still open and pointing in the right direction.

I’ve got no issue with technology that prevents or mitigates a crash – such as ESC or AEB. These have saved countless lives. But on our roads, there was already a crisis of inattention. At what point do we hit the brakes on computer-assisted semi-autonomous features that only reduce driver buy-in further?

The robots might be chauffeuring us around at some point in the future, but not yet. Drivers still need to drive, and pay attention to the road around them, lest they are given a rude shock at how reliant on these technologies they’ve become.

Not all of them will find out by reversing an old Toyota into a tight garage.

We recommend

-

Advice

AdviceCan you permanently turn off Lane Assist technology?

Lane Assist tech is critical to maximising safety (in theory), but can you side-step this at-times overbearing and annoying system?

-

News

NewsAutonomous Emergency Braking mandated on new cars from 2023

Future vehicles will feature AEB technology by law to reduce road accidents

-

News

NewsStability control of the future will be able to predict wet roads

Continental reveals its next-generation stability control tech will use data to make slippery roads feel like dry ones