We called it O’Grady’s Well. It was the largest most outstanding native well any member of the party has ever found. Down this, holding on to ropes linked together, I climbed until it became too dark to see. Peeping ahead with a lighted candle I espied a little pool of water where the lubras had left off work.

So wrote Michael Terry in his book, Sand and Sun, regarding his visiting of this important native well, known to the locals as Ylalya, when he was exploring the remote areas of Central Australia in 1932. (See the feature on Michael Terry’s treks in 4X4 Australia, July 2015).

When a friend of mine, Willie Kempen, (long-time readers may remember his contributions back in the late 1980s and early 1990s of his adventures – he is still out there doing it!) said he had a Central Land Council permit to go to O’Grady’s Well, my hand was up like a flash to join his small group of adventurers.

After meeting in Alice Springs a few weeks later, our five-vehicle convoy pulled into the community of Nyrippi in the heart of the Tanami Desert, around 360km north-west of Alice and 150km west of the main Tanami Road.

The route west from Tanami Road had taken us through Aboriginal land and we camped for the first night close to a spectacular but un-named gap in the Siddeley Range. From a vantage point on the hills we could see a line of peaks to the south-east jutting up from the surrounding flat sand plain. The most prominent of these peaks was Central Mount Wedge.

Our 1:250,000 maps also showed a waterhole nearby and after a short search we found it tucked up at the base of some cliffs in a fold of the range. Zebra finches flittered in from the nearby bushes for a speedy drink from the life-giving water, but that was the only movement we saw in this secluded spot.

The next day we passed through Newhaven; the one-time pastoral property that, some years ago, had been acquired by Birdlife Australia and the Australian Wildlife Conservancy. It’s now run as a conservation park. Camping is allowed on this remote property and bird watching is encouraged, but we pushed along past a sign that read: ‘Private track – use at your own risk’.

Quite suddenly we arrived at Nyirripi, a community of around 150 people – although at most times there are considerably fewer inhabitants. We found the well-stocked store and fuelled up with diesel for the vehicles and chocolate bars for the people.

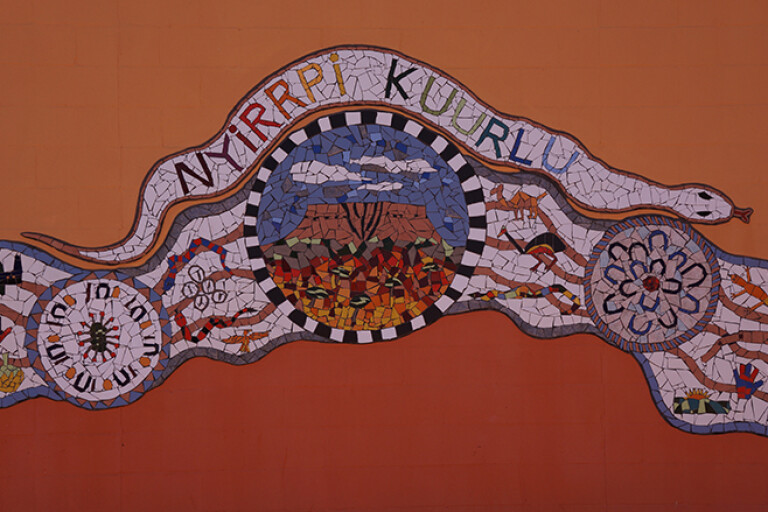

We also met a number of traditional owners who gave our trip their blessings and allowed us to photograph the spectacular mural that graces the local school. We were also told that they were hoping to set up a small tourist campground among the spectacular peaks to the south of the community.

That evening, after travelling on little-used tracks from Nyirripi, we were skirting along the edge of Ethel Creek on a track that was about to vanish completely into the surrounding grass and spinifex. Amongst this verdancy we had trouble finding a campsite free of vegetation.

When we finally set up camp, disaster almost struck when a small campfire licked flames into the nearby grass and fire erupted quickly around us. A hastily grabbed bucket of water, a couple of fire extinguishers and a fire blanket had the flames under control, but it was a near thing and a valuable lesson on how quickly disaster can strike out here.

Next day we turned off the track, struck west and followed the wheel marks left by a group of traditional owners and aboriginal rangers who had been out to their traditional lands. We soon left these ephemeral marks as they swung north to areas we didn’t have a permit for.

The first few kilometres further west, over flat grassy spinifex plains and between, what at first were, widely spaced dunes, was easy going. Our plan was to head west and cut south of the McEwin Hills – an area our permit forbade us to visit – bypassing them by at least a kilometre.

The vegetation soon changed, subtly at first with the spinifex clumps getting bigger and the waving fronds of seed heads taller. We passed through a band of thick low verdant scrub of spindly wattle, dense cassia and emu bush. Rain had fallen across much of this country a couple of months previously, so in places amongst the scrub and spinifex were splashes of brilliant colour from myriad daisies, flowering honey, rattlepod grevilleas and corkwood hakeas.

We’d swung south to the edge of a dune as we tried to get away from the thick scrub, when a call over the UHF told us of the first puncture. A quick plug repair and we were off again, but we’d driven less than a kilometre when our little convoy growled to a halt with another radial tyre whistling to empty.

Both Willie and I, who were up the front busting scrub, had previously fitted our Patrols with tough MRF cross-ply tyres, while those following us were driving on radials. Certainly the MRF tyres are a dog of a thing to drive on bitumen roads, but out here in untracked country they’re worth their weight in gold.

At one stage, Willie’s Patrol smashed into a conglomeration of dome-shaped limestone rocks hidden by the thick grass and spinifex. These outcrops, which may cover an area of many square metres, are by all accounts the remnants of ancient mound springs (the main structure of the spring having eroded away). They are hell to hit unexpectedly in a vehicle and it was lucky that Willie’s tough old Patrol bounced its way through relatively unscathed.

That evening we pulled up in a large cleared patch of sandy plain for our night’s camp. Dotted across the sand were scattered clumps of daisies, common firebush, purple parakeelya and the muted pastel colours of mulla mullas. A few taller grevilleas and hakeas, plus the odd drooping desert oak, completed the scene and made for a very pleasant camp.

As we approached the Sandford Cliffs early the next afternoon, thick bands of scrub thwarted our progress – at times we were even driving blind with scrub taller than the windscreen hindering our way. Suddenly we were amongst large clumps of tea-tree, with the spinifex giving way to grassy tussocks. It was much easier going here and it was also a sign of better-watered country, as the water from infrequent storms ran off the rocky slopes of the nearby Sandford Cliffs.

I’ve searched for a number of native water holes and rock holes during our remote desert travels and rarely are they found easily. In Sun and Sand, Terry describes O’Grady’s Well being found at the eastern end of the Sandford Cliffs, and he had approached the cliffs from the east as we were doing. We pulled up close to the cliffs and spread out, our party all keen to find the well. And it was remarkably easy, with my mate and travelling companion, Neil, spying it from a lofty rock he had climbed.

Lying in an almost imperceptible creek bed that ran from a low rocky amphitheatre, the well was located just 50 metres or so from the more dominant rocky cliffs at the south-eastern end of the cliffs. Surrounded by tea-tree, it was much smaller and shallower than when Michael Terry had first seen it, being only about five metres below ground level with no water in it – though I’m sure with a bit of digging, water could be found in there.

It’s obvious that when rain does fall here a lot of silt gets washed down the creek and fills the well. So in days past, the aboriginal people would have kept busy keeping it clean and accessible to its reported depth of 10 metres or more. Even though it was shallower and not as big as first reported, we were mighty pleased with ourselves.

We spent the next day exploring around the rocky hills and found the odd small cave and overhang, but little else. We saw very little sign of life with no wallabies or kangaroos present, although we learnt from their droppings that they sometimes used the caves and overhangs for shade and protection. We got the impression, though, that these isolated cliffs were rarely used.

The next day saw us heading back east. Once we made the track network we turned south heading toward the outstation of Emu Bore. We took a new mining track we had been told about and given permission to use by one of the traditional owners at Nyirripi. At Emu Bore we picked up another track which headed south and then swung west for a long run down a valley between the east-west dunes.

We arrived at Kalipima Native Well and were side-tracked while trying to find the water point amongst some tall gum trees and coolibahs. Eventually we found the well a few hundred metres south, its dry depression attracting wandering camels by the look of the churned up dust bowls which the large animals used for a dust bath nearby. From here the track swung east to run between the dunes again, before swinging south and eventually coming out on the Gary Junction Road at the Sandy Blight Junction.

Our adventure was nearly over as we turned east for the run back to Alice Springs. Now, having been to two of Michael Terry’s most note-worthy destinations – the other was Chugga Kurri, which I visited in 1990 – I only have one more to go, but the Cleland Hills will have to wait for another day.

Click here to learn more about Michael Terry.

Get the latest info on all things 4X4 Australia by signing up to our newsletter.

COMMENTS