IT CAN be hard to spot an obsessive in the wild.

First published in the April 2017 issue of Wheels Magazine, Australia’s most experienced and most trusted car magazine since 1953.

If they’re not cradling their chosen lust item or yammering on about it, only an ever-so-slightly unhinged glint in their eyes gives them away.

That, or a forefinger that’s double its normal size and radiating pain from two layers of blisters.

SLOT HEAD – IAN RICE, SYDNEY That’s what slot-car fanatic Ian Rice, 55, shows us on his “trigger finger”, the result of competing in an eight-hour race. Yes, eight hours of blokes standing around playing with toy cars. How did some OH&S person not see the dangers?

“My problem is that I’m going down the straight thinking if I squeeze the trigger to 11, I might go a little bit faster. The other guys are more relaxed about it.”

Rice is even less relaxed about his slot-car collecting. He has more than 600 of them, 90 percent of which have never come out of their boxes, while the rest are raced – which he is happy to describe as an obsession.

“With my Porsche 917 section, it’s complete now, but before it was I almost couldn’t sleep. It got to the stage where I just kept going, ‘Are there any more models I don’t know about; any other models I could have?’ I needed to keep researching.”

Finally finishing his 917 collection – a period of prolific spending that involved buying as many as eight $200 slot cars at a time – didn’t put an end to the compulsion, of course, and now he’s “going hell for leather after Ferraris”.

The reason he’s never taken most of his cherished cars – machines built to be raced, let’s not forget – out of their boxes is that oily human fingers would reduce their worth immediately. So does he collect them for investment purposes, or for joy?

“If I find out something’s in stock, I’ll stop what I’m doing, I’ll stop work, I’ll drive to the shop. There’s a huge rush associated with that, the rush of finding it and the rush of holding it.”

Josh Stebbing: Junior car collector

Rice’s slot-car love has been driving him around the bend since he got a Scalextric set for Christmas at the age of five. By the time he was 14, he and two mates were mirroring the F1 season in miniature every week.

“When the German Grand Prix was on, we’d build the German circuit in one of our lounge rooms, then qualify on Saturday and race on Sunday. I remember building a huge Silverstone once. I had to fold my bed up against the wall to fit it all in.”

That F1 fascination explains why he, and plenty of blokes like him, do what they do – meeting once a fortnight at Armchair Racer in Sydney to battle each other, wheel to wheel, on vast yet tiny tracks.

“The whole thing just reflects a huge, huge passion for motorsport. We’re all rev heads at the end of the day; that’s why we love it. We all just want to race, and own, the cars we can’t afford in real life.”

BOWSERHOLIC – MIKE MUNDY, GYMPIE When it comes to being addicted to impulse purchases, buying a house is right out there at the extreme end of the spectrum and makes a passion for collecting petrol bowsers, and other “garagenalia”, seem tame by comparison.

Mike Mundy, 59, admits that he has serious trouble walking away from any object he finds endowed with “vintage or classical” appeal, from motorcycles to swing sets to buildings.

“It wasn’t expensive, but I had to buy it because I just loved the look of the house so much. It hasn’t been the best investment, I didn’t know about the earthquakes…”

Finding beauty in things that wear the patina of the past has long been a passion for Mundy, who studied and then taught fine arts and design.

His particular love of petrol bowsers kicked off in the 1980s, and it’s since taken over his life as his collecting led to trading and selling, and to the establishment of a booming business in Australia and New Zealand called Roadside Relics.

“The interesting part is that, 15 or 20 years ago, collecting bowsers wasn’t cool, and people who did it then were quite strange and eccentric,” Mundy says, suggesting that people who collect “petroliana” are now as mainstream as philatelists.

Just as it might seem bonkers that people pay large sums of money for stamps instead of using the money on a car or a holiday, Mundy says he’s happily paid “car money” for pumps in the past. An immaculately restored Golden Fleece pump, for example, with the snazzy globe on top, can set you back $30,000 (no fuel included).

“I think they’re seen as cool now because they combine a good hit of nostalgia with great visual design, artwork and sculptural beauty,” Mundy says, attempting to make sense of those prices.

“But it’s not just older people who want petrol bowsers, it’s across the board, men and women, collectors in their 70s and people in their 20s. Petrol bowser collecting breaks down barriers between people of different ages.”

Mundy is also fascinated as to why petrol pumps of old were so ornate and artistic compared to the purely functional and unimaginative ones of today, and he sees the change as being analogous with car design – classic versus modern. In both cases, “things” just used to be more beautiful.

“I love the aesthetic of the old pumps, the quality of the artwork, the sign writing. The art deco ones are the petrol pump versions of the Chrysler Building or the Empire State Building,” he says.

“But I’m not an addict, because it’s my business now, so I can fairly say that collecting has become my whole life.”

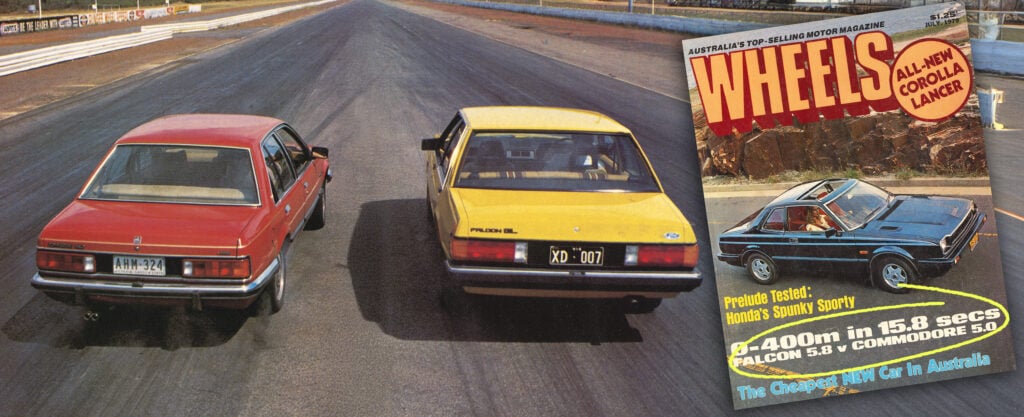

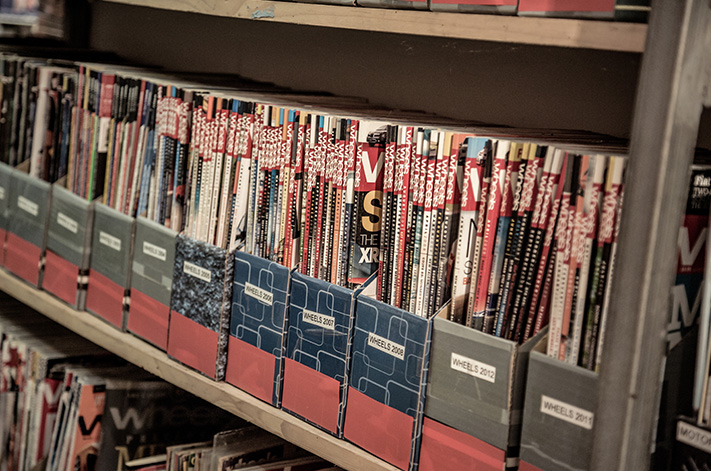

MOTORING LIBRARY CREATOR – HUGH KING, SYDNEY There is something serene, sacred and just a little scary about the billions of words under Hugh King’s huge house in Sydney, contained in almost 4500 books and more than 12,000 car magazines filling 150m of shelving.

For a mag lover like myself, it’s an astonishing and beautiful sight, but as an inherently chaotic, creative type, the almost surgical cleanliness and painful precision of the place – every book is precisely wrapped in “library-quality plastic”, labelled and catalogued – is unsettling.

The sheer size of his motoring library is mind-boggling, but he explains how it grew so big with wonderfully disarming simplicity.

“I started collecting in 1954 and I’ve never thrown a single thing away, and I’ve never traded or sold anything either, it’s all here,” he says with a shrug of pride.

While it seems to cover every kind of car or motoring-related endeavour of the past century, King points out that he’s actually been quite “discerning” and that his thousands of books concern only vehicles actually built or sold in Australia.

“It’s about your personal make-up, I guess, and I’m a light sleeper and I still only sleep four or five hours a night, so I use that extra time for reading, but I’m also a very quick study. Being a lawyer, you have to be,” he says.

King also seems to have a memory the size of a planet. Pluck any book, on any topic, from the shelves and he’ll regale you with an enthusiastic summary of its contents, its provenance and its cost.

Every book has a story, but none more important than the aged, Bible-like bound volume of Autocar magazines from the UK, dated 1925.

“I would sit up, age eight and nine, reading it by kerosene lamps, and I began to understand what makes cars work. And I would put grease-proof paper over the pictures and trace the cars. I read it so many times.”

For sale: Unused Porsche 911 Carrera RSR 3.8

That book led to a monthly investment of almost his entire pocket money in Wheels magazines (he’s never been a subscriber as he doesn’t like his copies being wrinkled in the mail), which led to other car magazines from around the world, and then to books, and more books.

His wife must be very understanding, I suggest, and he points out that he does keep his collection neat and that it’s a lot less likely to cause a divorce than collecting expensive cars, which was always a temptation.

King, who has resisted offers of more than $700,000 to break up and sell off his collection, wants his work to live on and has, along with Robbo and a select group of others, set up the Australia Motoring Heritage Foundation, which hopes to establish a museum at Sydney Motorsport Park, built around his life’s passion.

“I want all this to be a legacy for a foundation. I want to lie on my deathbed and think, ‘well, at least it’s okay’,” he declares, with real emotion.

And somewhere very, very organised, obviously.

“EVERYTHING” COLLECTOR – WILL HAGON, HUNTER VALLEY How much is too much? That’s a question that a proper obsessive simply never asks, or answers. Even when the shed he needs to contain his collection is almost bigger than his house, or when he realises that he’s spent more money on storing the stuff, over three decades, than it’s actually worth.

Will Hagon – a man whose booming voice you instantly recognise thanks to a tireless, 50-year career as a motorsport commentator – has been described by his friends as the only man ever to buy a warehouse conversion, only to turn it back into a warehouse.

“I’m not good at culling stuff, because all these things help to inspire memory, and it all has personal value to me in some way, and I love the rediscovering it provokes every time you find something and remember.

“Like buying magazines, they just seemed almost biblical, it seemed so important, you loved it so much – the trip to the newsagent to buy the Australian Motor Sport magazine and read the news.

“I’ve certainly spent lots of money on storage, which probably says that I’m a true collector, in the sense that I’m not going to do the mathematics, because the numbers would tell me to save the money and get rid of the stuff, but I love the stuff too much,” he says, toppling into the titter that so remarkably offsets the manly bass of his radio voice with its impish pitch.

Back in 2006, he moved his widely dispersed collection of models and memorabilia from Sydney to a single location in northern NSW, where he opened Will Hagon’s Kew Pit Stop. It took five trucks packed with more than 400 cartons to carry it all, and only half of it was unpacked into the shop/museum.

The Pit Stop has since closed and the collection is now finally in a single sizeable shed (measuring 9m by 9m) into which it only just fit, and Hagon is not paying someone else to store it all, for the first time in 30 years.

What’s even more astonishing than the size of the collection is its scattered content.

Unsurprisingly, Hagon is still collecting – he points to an almost full bookcase that contains only the books he’s bought so far this year – and he admits, ruefully, that he’d probably have a lot more in the shed, or another shed, if it wasn’t for his mother and wife.

“I think back to toys that I had, models I had, and so much that I wish I’d kept just disappears, and you never know why. But you know what women say, ‘You haven’t used that for three months, now throw it out!’”

Hagon is a big man, with an even bigger presence, but even he is dwarfed by the size of his collection. It truly has become larger than his life.