It reads like a film script … THE SCENE: A narrow, twisting road through the wildly beautiful Swiss-Italian Alps … THE CHARACTERS: A famous author and his film star wife living in a mountain hideaway … THE PLOT: The chance discovery of an Italian masterpiece …

THIS, I SWEAR, is exactly the way it happened.

It was in September, 1963; Jasmine and I had been living in Turin for three months and were on our way to Locarno, Switzerland. As our red Fiat Seicento (600) hummed across the Po Valley and along the western shore of Lago Maggiore we kept up our instinctive vigil for cars of character.

There were few left in Europe. But as we tooled past Arona we saw something parked in front of a modest garage. It was a big, black Fiat 524 limousine of 1934 vintage and in very good condition. The owner turned out to be the proprietor of the garage, a small, wiry, salt-of-the-earth Piemontese in coveralls and beret, with a radiant personality and a passion for the fine machines of the past. After we had examined the Fiat we went up to his apartment over the garage for a splash of barbera. There we met his family and when we parted we did so as close friends, with a business card of Cavalier Tale tucked away for reference.

As we continued north along the edge of the vast lake the country became more mountainous and wildly beautiful and the road more twisting and narrow, with almost sheer cliffs on the left and an abrupt drop to the water on the right. Then, just a few miles beyond the Swiss border, a gleaming, flame-red Lotus Elite pulling a flat trailer came straight at us. And on the trailer was the most pristine Jaguar SS100 we had ever seen. It had racing numbers painted on its bright yellow sides. Evidently a discriminating Swiss enthusiast on his way to a hill climb.

At the same, precise instant, as my eyes were riveted on this spectacle, Jasmine cried “STOP”! with panic urgency. Standing on the brakes I warped onto the narrow shoulder and let the giant OM diesel that had been on our rear bumper thunder by with millimetres to spare.

“Look!” Jabs said, pointing to an open cave hewn out of the cliff face. “What is it?”

I couldn’t identify the vintage machine from the rear but she had been right – it was something very special.

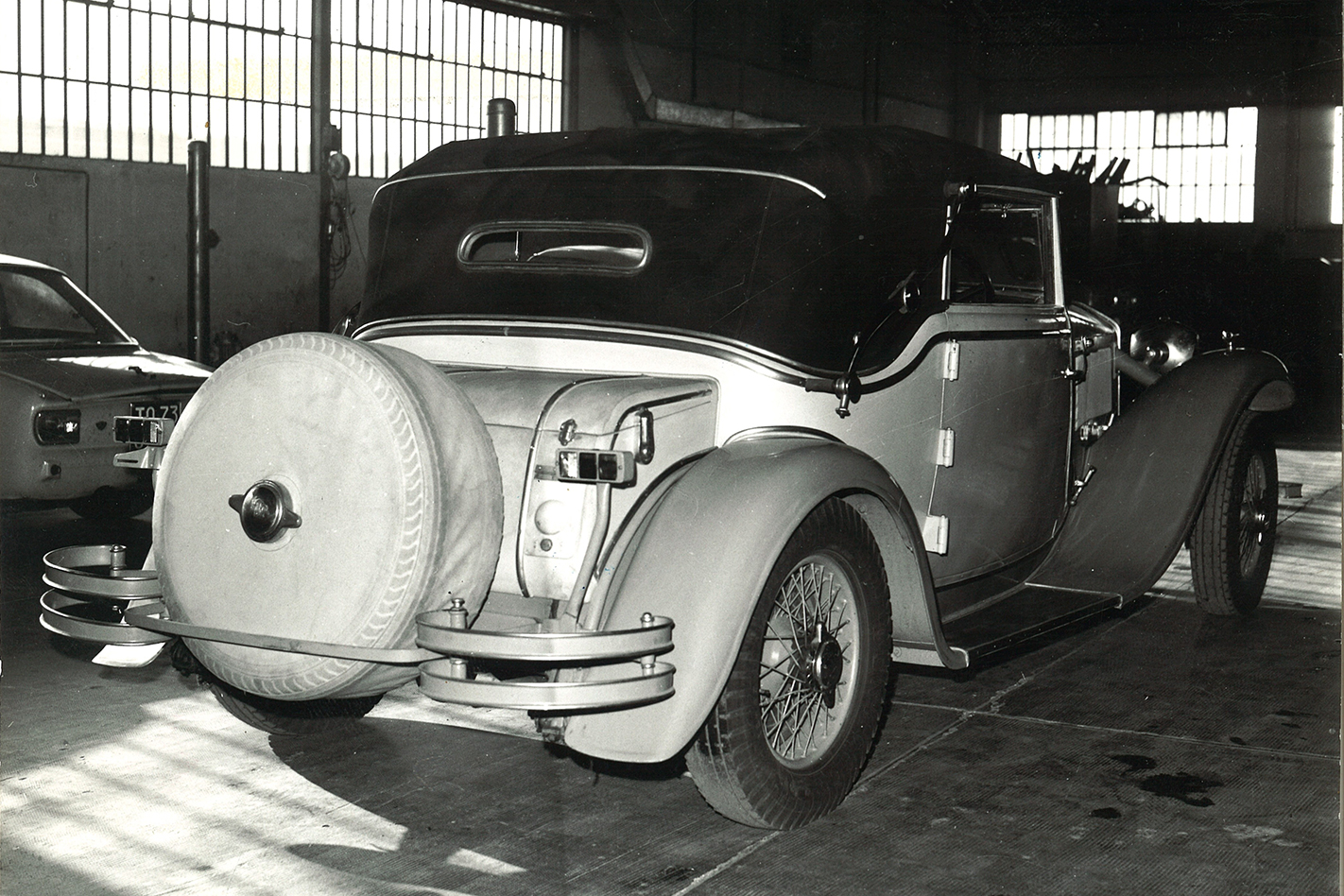

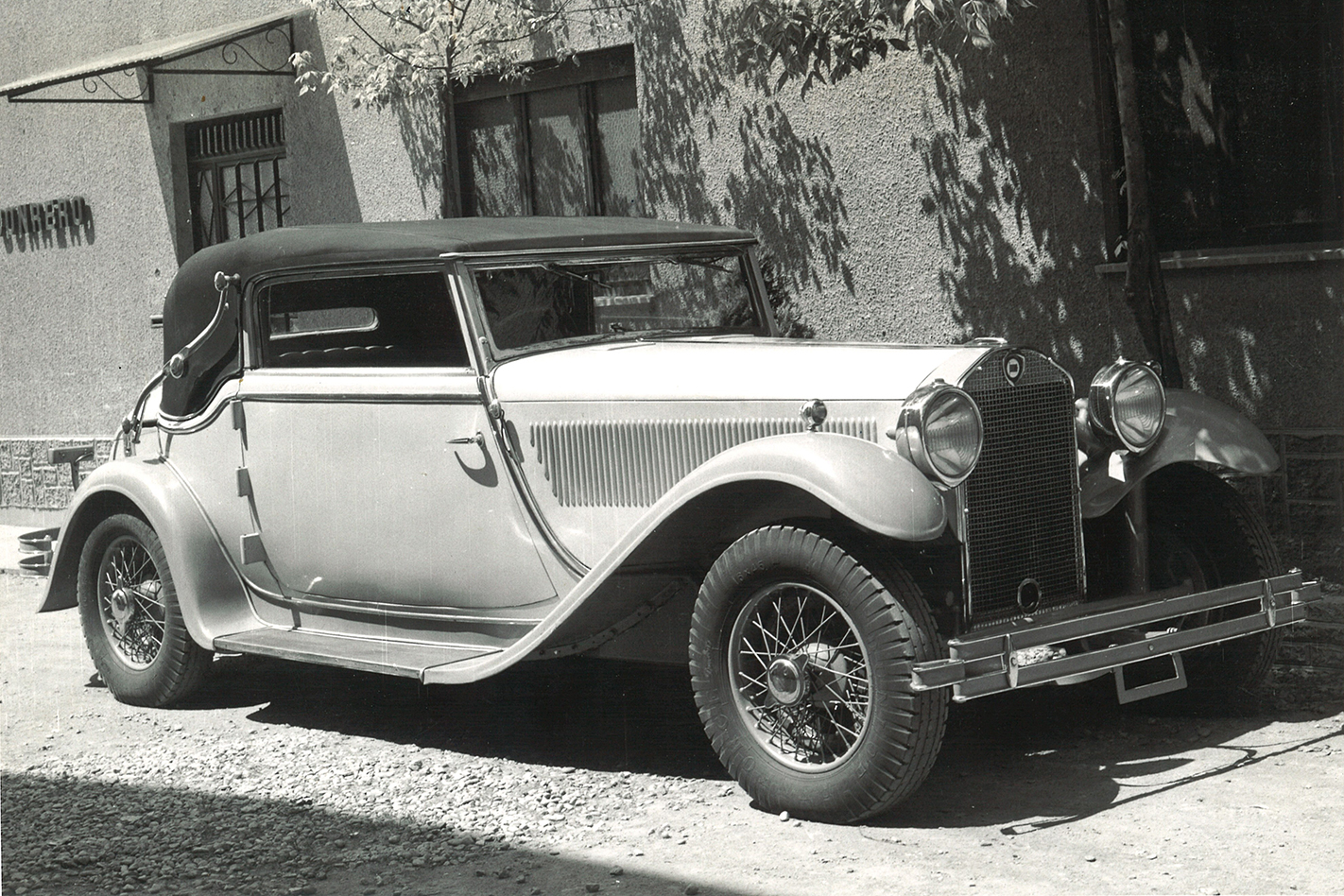

We got out and entered the doorless cave-garage. The first glimpse from behind of the lines of the car’s radiator proclaimed the close-coupled landau was a Lancia Dilambda.

In Italy, where the Dilambda is known as Vincenzo Lancia’s capolavoro, his masterpiece, only five of these cars were known to survive. This one, beneath the dust of years, had the finest lines of any specimen we had seen.

Someone had carefully placed it on blocks a long time ago. Its big tyres were like new and only 41,000 km (25,500 miles) were registered on its odometer.

It had been all of a year and a half since we had finished restoring a splendid old car. We looked at each other in a silence that said, “Should we?” Finally we both nodded, resigned to what Fate was doing to us, and I said, “Wait here. I’ll start looking”.

There are villas perched high on the cliff there and they are reached by hundreds of steps cut into the rock.

When I climbed to the third house I found someone who knew who belonged to the old car. “Oh yes,” said a lady in Italian. “It’s Signor Remarche, down there across the road, beside the lake.” It had started to drizzle and Jasmine sat in the Seicento while I pursued the warming trail.

The villa was exquisite, surrounded by an acre or two of jungle-like garden. I knocked on the front door but, although there was sound within, there was no answer.

I went around to the back of the house and mounted a broad veranda, where a wall of glass doors faced the lake. I knocked loudly, to be heard over the recorded voice of Caruso which rang through the serene air. The door was opened by a stern-looking, silver-haired man in his sixties.

“Mi scuso,” I said. “Ma cerco il Signor Remarche.” “Sono io,” he answered. “Cosa volete?”

I explained I was interested in the old car, perhaps in acquiring it.

“You can speak English,” he said, with a very light accent. “Come in. I can give you just five minutes. I have a pressing engagement.”

The golden, open voice continued to flow from the sound system. My eyes made a quick sweep of the huge room we were in, noting its richness, its lack of any pretension, the books and ancient bronze sculptures everywhere, a huge rustic table stacked with manuscripts. I asked myself, what is his name, not pronounced in Italian?

“Pardon me,” I said. “Would your name be Erich Maria Remarque?”

”Yes,” he said. “That is who I am.”

For the benefit of those who are not familiar with the name, Remarque was one of the great authors of this century. He died in 1970. His first book, All Quiet on the Western Front, was revolutionary in its literary style, as it was in its profoundly moving expression of the tragedy of war. It was the beginning of a long and brilliant literary career.

Having been warned this encounter must be brief I hastened to the point: Would he consider giving up the Dilambda?

“Many people have come here asking that question,” Remarque said, “But I have resisted. Too many of them were obvious speculators. Tell me about yourself. What do you do?”

I told him I was a motoring writer and defined my main spheres of interest.

“Very interesting,” he said. “Because that’s how I began writing. I worked for the Continental Rubber Co in Germany as a technical writer. That was how I came to know the whole Mercedes racing team in the ’20s. Caracciola was a close friend. It was he who taught me to handle a spur-cut gearbox properly and how to handle a good car at speed. In the Dilambda I used to love to take on big, supercharged Mercedes on any twisting course and leave them behind. The Lancia’s independent front suspension and roadability were formidable things then.”

The five minutes stretched into 20, then 30, and the rain came down. Remarque asked if I had come alone and I told him my wife was waiting in the car. “Good heavens,” he said. “Bring her in! My wife will be here at any moment. She’s American too, you know. Her maiden name is Paulette Goddard.”

I fetched Jasmine, Erich broke out the Cognac and baccarat glasses so thin they were elastic to the touch. Paulette arrived and he said. “Mamma, these are the Borgesons, from the States and now living in Turin. We have a thing or two in common.” La Goddard had just come in from having her hair set and had a scarf around the rollers. She was beautiful and as natural as any of the villagers. Jasmine didn’t know who she was but they fell to reminiscing about Southern California like old schoolmates.

From time to time the conversation would drift back to cars and Paulette told us of an odd coincidence. As rare as Dilambdas always were, she had owned one when she was a bit player working for Republic Pictures for $35 a week. That was before she became a great actress. Her beau at the time was Crane Grantz, heir to a famous fortune, great automotive enthusiast, and founder of the Cragar racing equipment, which still exists as a division of Bell Auto Parts of Los Angeles.

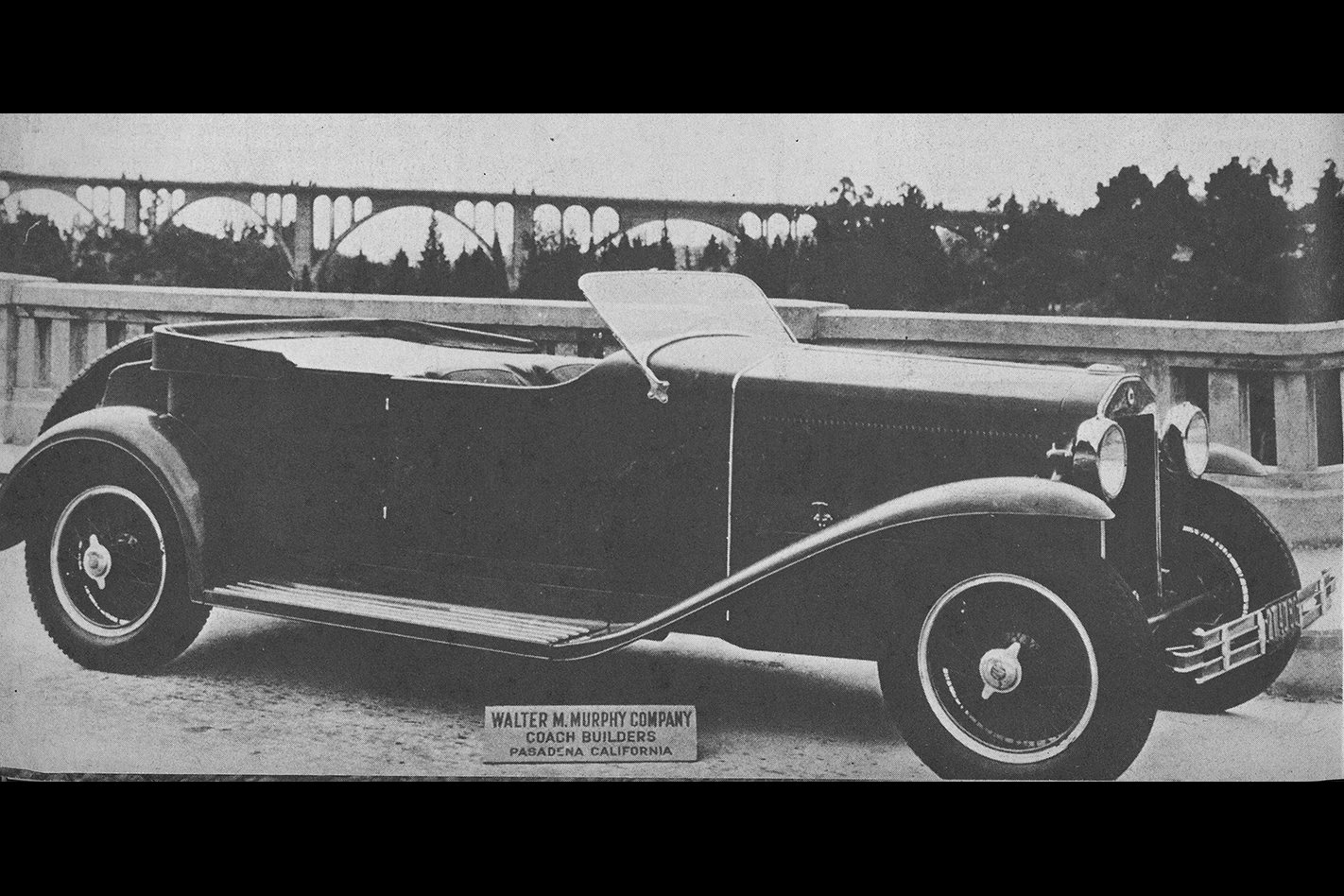

“Cranie” had made Paulette the splendid gift of a brand new Dilambda with a short chassis like this one, and with a close-coupled Weymann four-seater body. Driving it to Palm Springs one time she became confused at the junction, hit the signpost in the centre of the road fork, and under ‘the impact the whole fabric body flew off, leaving her holding the wheel of a bare chassis. Back in Turin I had a photo of her car, taken when the Walter M. Murphy coachworks of Pasadena put it back together, and I brought it to Paulette on our next trip.

After a couple of hours this session had to end. “Think about the Dilambda and I will too,” Erich said. “Maybe we can work something out. There’s no hurry. I don’t plan to sell it to anyone else but we do need the space.”

The car was in beautiful condition. It had been driven only once in the last 14 years, when Erich took Paulette to Venice on their honeymoon. Yes, we wanted the car, and, living in Turin, there never would be a problem finding replacement parts or having them made expertly – if they ever should be needed. The decision was probably much more difficult for Erich.

He had told us a great deal about what the car meant to him. As a technical writer he had hardly been prosperous. He wrote his first novel, “All Quiet“, at night and then traipsed from publisher to publisher in Germany, trying to sell it. The universal response was that the last thing that anyone wanted to buy at that time was another war book.

Finally, Erich did find a publisher who took the trouble to read the script, thought he saw merit in it, and decided to take the risk. When the book appeared the first edition sold out almost overnight and the demand for it rose to legendary heights – until the task of keeping up with this demand had to be farmed out to some 80 different presses in Germany. Meanwhile, its success beyond those borders was equally fantastic and it was translated into nearly as many languages as the Bible. As a film, which lifted Lew Ayres to stardom it became one of the classics of all time. It had a profound influence on a whole generation of the human race.

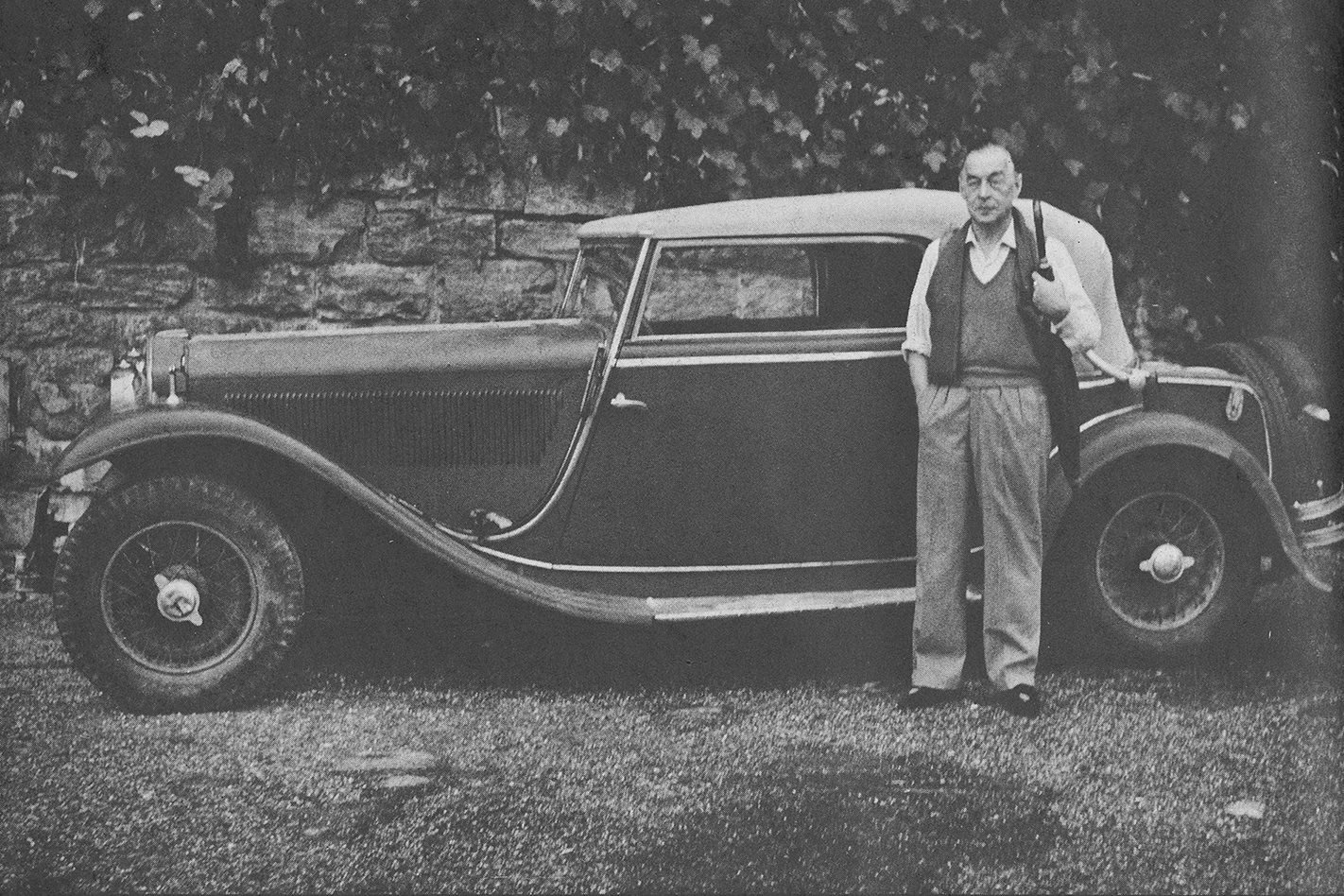

Erich, of course, found himself suddenly wealthy. He continued to live modestly but, with his first royalties in 1929 he indulged himself in the fulfilment of a dream: a Lancia Lambda roadster. Then in 1932, wanting a more powerful car he bought the Dilambda chassis from the Lancia agent in Berlin and commissioned the landau body to be built by the coachbuilding firm of Voll & Rohrbeck there. This car became very dear to him, particularly since he feels it saved his life twice.

Erich found himself in a Spockian position in the Germany of the ’30s: an enemy of the State because of his persuasive pacifism. He was subjected to constant harassment, which the establishment sought to justify by releasing the myth that he was a Jew named Kramer who was hiding under the name spelled backwards. One day an admirer of his with close party connections warned him of orders for his arrest within 24 hours. He loaded the Dilambda with all the essentials it would hold and fled over the Alps, to Antibes on the Cote d’Azur.

That was his first escape. He remained in the South of France, writing, until well into World War II. Then one day he received a telephone call from another admirer, ‘this time the late Joseph Kennedy, then US Ambassador to Britain. Kennedy told him he had positive assurance that the Germans would invade France within hours and that Erich should flee unless he wanted to be dealt with as a traitor to the Third Reich. Again he hurriedly loaded the Dilambda, this time driving to Italian Switzerland. It was then he settled in his present villa. They were close comrades, he and the Dilambda.

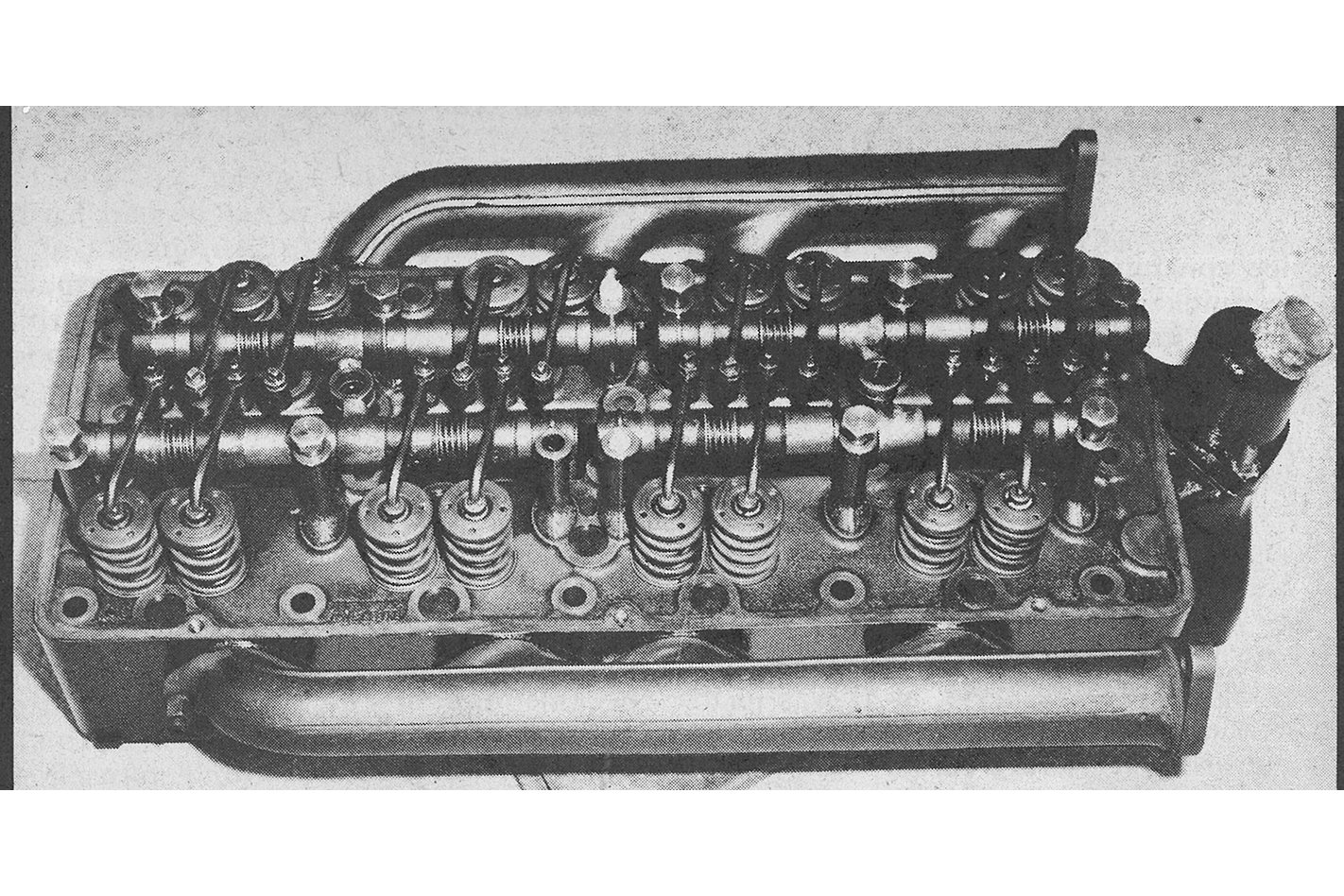

In a month Jabs and I returned to Lago Maggiore and it was agreed we should have the car. The next problem was putting it back in service sufficiently to drive it to Turin. This involved many weeks of commuting between the two points as each aspect was dealt with systematically. All went perfectly until I turned the crankshaft a few degrees, levering the flywheel ring gear. There was a brittle, snapping sound as a rocker arm fractured. Not surprisingly, ancient varnish had welded most of the valve stems in their guides.

I removed the cylinder head and, on the way back to Turin, dropped it off with Cavalier Tale, about 40 miles down the lake. He would free the valves while I found another rocker arm. Knowing the Italian Government does not award Knighthoods without excellent reason, I asked him how he had acquired his title. With pride he showed me his membership card in the American Knights of Colombus which he had somehow managed to acquire.

I got off an SOS to our soul-mate Ronald Barker in England, knowing that in the loft over the carriage house which holds his famous Napier and Dilambda are stored most of the world’s stock of Dilambda parts. The rocker arm came back by return mail and we headed back across the Swiss border, picking up the reworked cylinder head on the way. I torqued it down and, with a borrowed Land-Rover, had the Dilambda given a starting tow. After a few dozen yards in third gear the four-litre V8 burst into sonorous life, and after a couple of hours of shakedown promenade we were ready for the trip back to Turin. Mamma Remarque handed Jasmine a sweater she had knitted and Erich came up to the road to see us off.

I drove the Dilambda, and it was a rich experience. It is one of those all-of-a-piece thoroughbreds that is all honesty, integrity and quality. After just a few trial shifts it became easy to go through the straight-cut four-speed gearbox without a nick. The steering was quick and precise, the huge brakes were powerful, the acceleration stimulating, and the ride was luxurious and at the same time rock-solid.

Jasmine followed in the Seicento and at the border we faced the moment of truth with Italian Customs. Erich had last registered the Dilambda in Switzerland in 1954 and I, for tax reasons, had registered it in the States and had mounted the American licence plates. This meant saving astronomic quantities of lire for as long as we could get away with it. At this, the most crucial point of the exercise, we were lucky.

Doganieri poured out to admire this glory of Italy’s automotive past and the incident turned into a great bench-racing session. There was one grouch who, probably under the influence of Ian Fleming’s “Goldfinger“, did his best to find ingots aboard. Back at the Seicento another officer said to Jasmine, “Oh, we know who you are, incognito and all. You’re that writer and actress couple that lives up the road.”

We entered Italy through a portal of smiles and arrivedercis.

It was pitch dark as we neared Stresa, two thirds of the way down the long lake. The Dilambda’s engine began to run on fewer and fewer cylinders as the valve stems again began to lock up in their guides. I pulled up under the first street lamp on the outskirts of the small city, to verify the nature of the trouble. Somehow Jasmine managed to flash past without either of us being aware of it. I waited for her momentary appearance but the minutes dragged by. After half an hour I knew she was in trouble, perhaps had fallen into the lake, which is not hard to do. I hiked to the centre of Stresa, found a policeman directing traffic at the main intersection, and asked him if he had seen a red Seicento go by, with Stampa sticker and Turin plates. He had not, so l asked for directions to the police station and hiked there. It was a desperate move, because Jahs’ driver’s licence was about as legitimate as the Cavalier’s title.

I explained the situation to the officer on the desk. I was an American writer living in Turin, my wife and I were driving there in separate cars, and we had lost each other. Did they have any word of her? No. I did not want to move the Dilambda, wanted to leave it under the street lamp where she surely would see it if she should come by. Could they take me back toward Switzerland in a police car to look for her? Or lend me a Lambretta? All this was too much for the desk officer, who said I had better tell my story to the commandant on duty.

This officer began taking notes suspiciously, obviously wondering what I was really up to. Then he asked me what I was driving. I told him, naturally, a 1932 Lancia Dilambda, with American plates. He looked at me as though I were both raving mad and making a mockery of his office. He brought his fists down on his desk when, with the inkwell still in the air, there was a great commotion in the ante-room. Jasmine burst in, weeping for joy.

Having lost sight of me she had assumed I had floor-boarded my way on to the Cavalier’s. She drove the twenty miles there, found I had not been heard from, drove the twenty miles back, and was trapped by the officer at the intersection. He brought her to police headquarters, where our great reunion took place in an atmosphere of universal emotion. All the cops were happy we had found each other with the exception of the commandant, who probably still feels it was all a cheap publicity trick cooked up by crazy, inscrutable Americans. We suspect they may still remember that night in Stresa.

We boomed south and routed the Cavalier out of bed. I told him how his valve job had worked out and he promised to correct it the first thing in the morning. Having had a full day, we collapsed in the handiest hotel. A few hours later I walked into the garage and found our lover of vintage machinery beating the Dilambda’s rocker arms with a large hammer. “They should be fine now,” he said and I agreed. Anything to stop the carnage. The car had come that far on three cylinders and might make it to Turin. It did.

Aside from the essentially simple valve problem the thing wrong with the Dilambda’s meccanica was its thoroughly rotted-out exhaust system. This meant driving with both windows down. This was quite acceptable since all the way across the Po Valley ice formed on the windshield as fast as my shivering hand could reach out and scratch a small hole in it for a clue as to where we were going.

Home in Turin I dismounted the cylinder head once again and found that the Cavalier, the first time around, had taken the trouble to remove the rocker shafts. He had beaten directly on the valve stems; most of which were so mushroomed it took hours of filing before the ruined valve could be removed. I had a set of new ones made, blued them into the reground seats, and Barker winged in from London with a new Dilambda head gasket, neatly protected in his valise by clean shirts and shorts.

The clearances of the pistons and lower-end bearings were minimal; I buttoned up the engine and it ran like a watch. Abarth, who does this work for Ferrari, among others, engineered a brand-new copy of the original dual exhaust system. Virgilio Conrero put the crowning touches on the engine’s tune. Fellow Dilambda owner Dr Paulo Sanguinette made us a gift of a pair of Dilambda fender lights copies of the original accessories which he had just had hand-made by Fausto Carello, the firm which originally had made the Lancia-shield-shaped headlights which had distinguished all Dilambdas. The remaining task was restoration of the coachwork. The old paint was finished, most of the chrome required replating, and the wood of the trunk and left-hand door was rotten.

Some of the best restoration work in the world is done by Carrozzeria Savio of Turin, to whom I took the car. Restoration is just a sentimental sideline for this busy house but they agreed to take the job on if I had lots of time and would let them work at it in spare moments, which would permit them to make a very friendly price. They were good to their word and their expert artisans did a splendid job, with just one hitch.

We had decided upon beige for the car’s body, top, and trunk, and tan for fenders, running-board valences, and radiator shell. The top came last and I inspected Savio’s stock of waterproof fabric. It was all black and it was only then I discovered it had been years since any other colour had been available on the Continent. I gave instructions to do nothing. I decided to track down properly matching material myself.

A friend who works in the managerial echelon of a major French manufacturer discovered a few yards of rubberised cloth of the correct tint, tucked away in one of his firm’s warehouses. Since there was no established procedure for disposing of such leftovers to the public, he just walked off with the cloth. He carried it to the Frankfurt Show where he turned it over to a mutual friend, a famous Torinese coachbuilder. He smuggled it home in the trunk of a show car and kindly delivered it to Savio, who installed it on the Dilambda. Then they wrote us, saying the car was ready for delivery at last. It had been a long time, by mutual consent.

In the interim many things had changed and, while Turin always will remain our mother metropolis in Europe, we had retreated to a more rustic base of operations in southern France. On the way to Monza in September, ’67 I stopped at Savio’s to see the finished car and to greet the firm’s director, Dr Caracciolo, who had made the project his personal responsibility. This kind gentleman had succumbed to a long illness and, as if in subconscious mourning, the top material had been installed with the black side out. These things occur with no one being at fault.

There is no denying the Dilambda would be nicer with a top which more closely matches its overall decor, but that concern is no longer ours. We made the decision between Turin’s broad boulevards and the narrow streets of sunny Provence where only tiny cars are any pleasure to drive. It is sadly ironic that the Dilambda does not belong with us. Erich’s eyes were not dry when we took his car away, and if it were Jasmine’s style to weep, she would now. It was she who found the car and loved it. But, as things worked out, she never got to ride in it and will not twist the knife by riding in it now. The Dilambda rests in Turin, where it was born.

‘A Dilmabda in a Cave!’ originally appeared in the May 1972 edition of Wheels.