THE end of manufacturing at Mitsubishi’s Tonsley Park plant in Australia has meant the loss of 930 jobs. John Carey uncovers exactly what went wrong, and meets the workers preparing for an uncertain future.

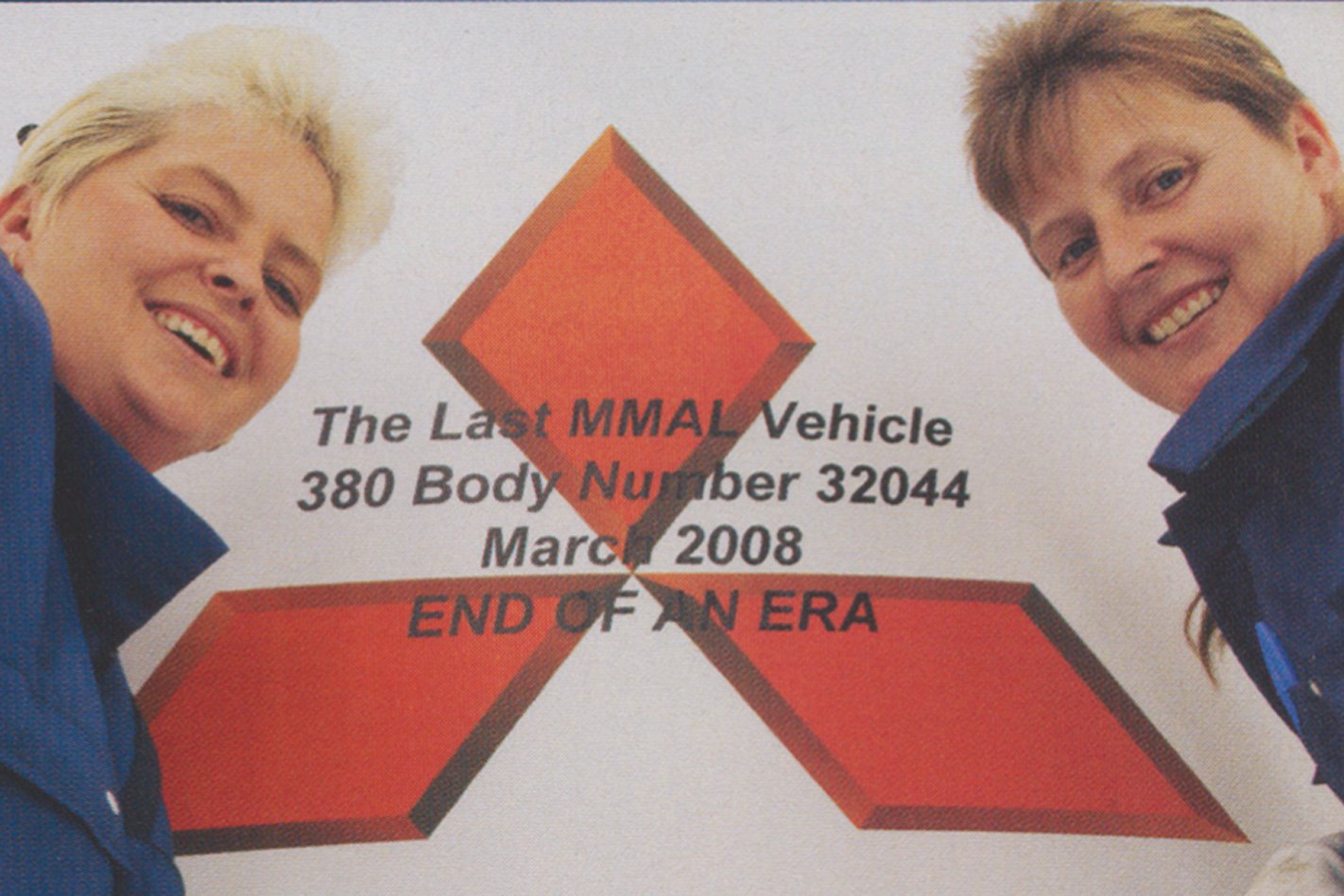

BEC DURBIDGE isn’t crying now. She’s wiped the tears from her cheeks, but her face still wears sorrow’s signature. The closure of the place at which she’s worked for most of the past 12 years is about to become very, very real. The last car body ever to pass through Tonsley Park’s paint shop will soon arrive. When the Mitsubishi 380 has been sprayed with its coat of platinum silver by Durbidge and the other paint shop workers, that’s it.

Finding Closure was first published in Wheels in May, 2008

Wearing the paint-shop worker uniform of baggy, blue, anti-static overalls, the 30-year-old is every bit as much a product of the Adelaide factory as any of the 1.5 million-plus cars made here since it was constructed back in the 1960s. Her parents only met because they both worked at the plant, back in the days when Chrysler was the name on the sign beside the gate.

If the plant wasn’t closing she’d be happy to keep working here, Durbidge says, as her eyes flick across the windowless, fluoro-lit space filled with the sweet aroma of solvents. Outside jobs she’s had at times just haven’t come close; haven’t had the spirit of Tonsley Park, she tells me. “The people bring you to work. They’re your family.”

Quite literally, in some cases. Brash, blonde Carol Rollins, who told me of Durbidge’s tears as the end drew near, poses with her brown-haired identical twin sister, Ann Regnier, beside the last 380 as it enters their part of the paint shop. Rollins’ husband works with the welded assembly group, where bodies are built. Tom Di Vittorio, who also works in the body build area, is, with his brother, the third generation of his family to work in the factory. Bee Durbidge isn’t the only worker to speak of the familial sense of community that somehow flourished in the sprawling factory. “It’s been a good family in here,” says stamping plant quality manager Bob Ormsby. He would know; he’s worked in the place for more than 36 years.

The news was delivered by Rob McEniry, Mitsubishi Motors Australia Limited president and chief executive officer. Minutes earlier, with other members of the MMAL board, the boss had learned that the board of Mitsubishi Motors Corporation, his company’s parent, had formally approved a recommendation to close Tonsley Park. Once word of the MMC board decision in Tokyo reached the MMAL board in Adelaide, McEniry retrieved a jacket from his office, pulled it on, and walked to the factory canteen where his 1200-strong workforce was gathered.

McEniry was the author of the Tonsley Park shutdown recommendation. He’d first read it to a meeting of the MMAL management committee on Friday February 1. It was accepted. The committee’s decision was minuted to the MMAL board, which met on Monday February 4. The MMAL board voted to forward the closure recommendation for consideration next day by the board of MMC, meeting in Tokyo. The Australian board also met on Tuesday, to await news from Japan. There was little chance of MMC ignoring the recommendation; the Adelaide factory had run up losses totalling $1.5 billion over the previous 10 years.

The Mitsubishi 380, the only car built at Tonsley Park, had been a problem from the beginning. A big, front-drive sedan with a 3.8-litre V6 engine, it had gone on sale just days before McEniry took over as MMAL boss on November 1 2005. For the factory to break even, perhaps make a little profit, the 380 needed to sell at a rate of 30,000 to 35,000 a year, but as the months passed, it became clear the car was only selling at one-third the required rate. It was damn near sales-proof.

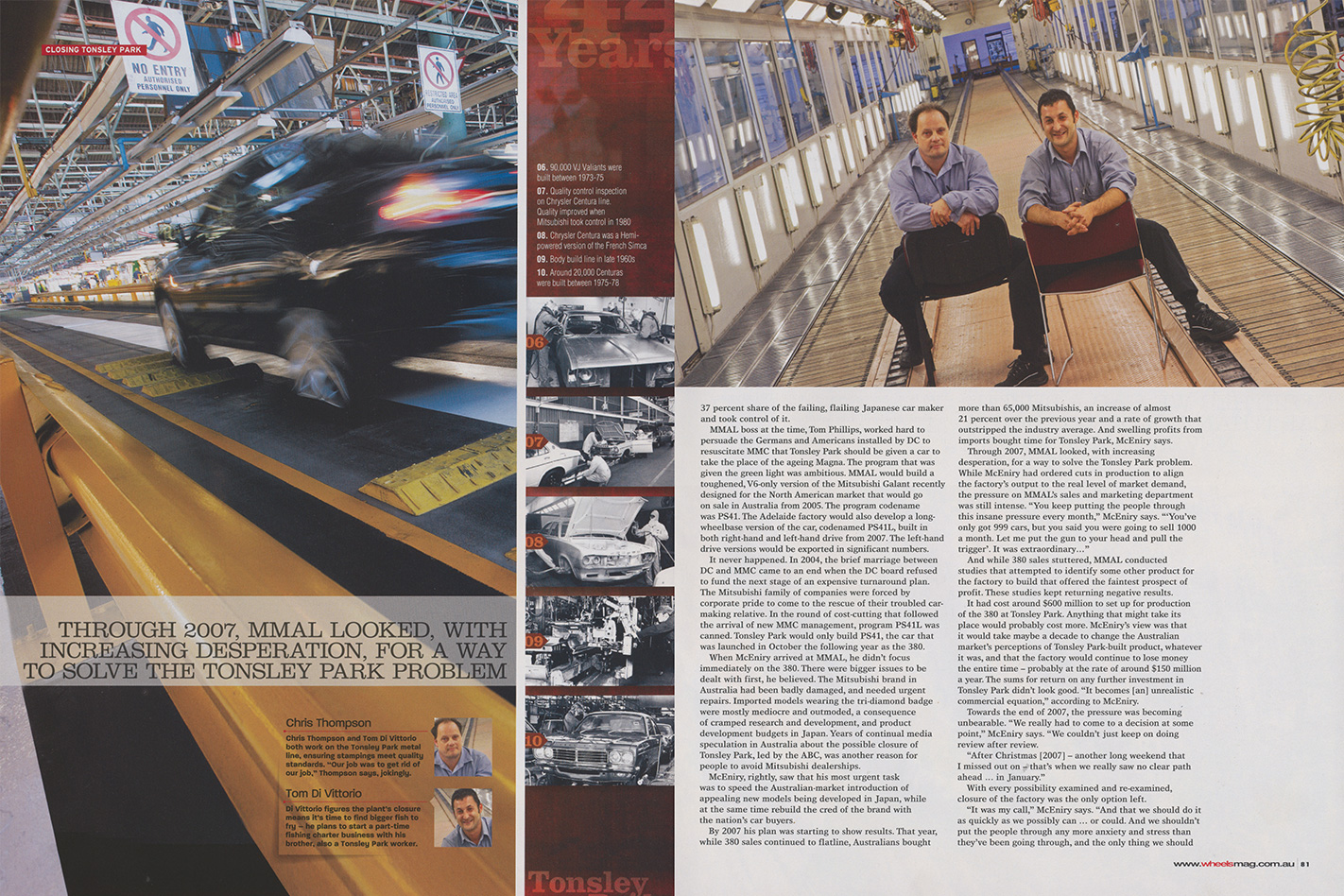

MMAL boss at the time, Tom Phillips, worked hard to persuade the Germans and Americans installed by DC to resuscitate MMC that Tonsley Park should be given a car to take the place of the ageing Magna. The program that was given the green light was ambitious. MMAL would build a toughened, V6-only version of the Mitsubishi Galant recently designed for the North American market that would go on sale in Australia from 2005. The program codename was PS41. The Adelaide factory would also develop a long-wheelbase version of the car, codenamed PS41L, built in both right-hand and left-hand drive from 2007. The left-hand drive versions would be exported in significant numbers.

It never happened. In 2004, the brief marriage between DC and MMC came to an end when the DC board refused to fund the next stage of an expensive turnaround plan. The Mitsubishi family of companies were forced by corporate pride to come to the rescue of their troubled carmaking relative. In the round of cost-cutting that followed the arrival of new MMC management, program PS41L was canned. Tonsley Park would only build PS41, the car that was launched in October the following year as the 380.

When McEniry arrived at MMAL, he didn’t focus immediately on the 380. There were bigger issues to be dealt with first, he believed. The Mitsubishi brand in Australia had been badly damaged, and needed urgent repairs. Imported models wearing the tri-diamond badge were mostly mediocre and outmoded, a consequence of cramped research and development, and product development budgets in Japan. Years of continual media speculation in Australia about the possible closure of Tonsley Park, led by the ABC, was another reason for people to avoid Mitsubishi dealerships.

Through 2007, MMAL looked, with increasing desperation, for a way to solve the Tonsley Park problem. While McEniry had ordered cuts in production to align the factory’s output to the real level of market demand, the pressure on MMAL’s sales and marketing department was still intense. “You keep putting the people through this insane pressure every month,” McEniry says. ‘”You’ve only got 999 cars, but you said you were going to sell 1000 a month. Let me put the gun to your head and pull the trigger’. It was extraordinary …

And while 380 sales stuttered, MMAL conducted studies that attempted to identify some other product for the factory to build that offered the faintest prospect of profit. These studies kept returning negative results.

It had cost around $600 million to set up for production of the 380 at Tonsley Park. Anything that might take its place would probably cost more. McEniry’s view was that it would take maybe a decade to change the Australian market’s perceptions of Tonsley Park-built product, whatever it was, and that the factory would continue to lose money the entire time -probably at the rate of around $150 million a year. The sums for return on any further investment in Tonsley Park didn’t look good. “It becomes [an] unrealistic commercial equation,” according to McEniry.

After Christmas [2007] – another long weekend that I missed out on – that’s when we really saw no clear path ahead … in January.” With every possibility examined and re-examined, closure of the factory was the only option left.

“It was my call,” McEniry says. “And that we should do it as quickly as we possibly can … or could. And we shouldn’t put the people through any more anxiety and stress than they’ve been going through, and the only thing we should be interested in, from this point on, is the people.”

McEniry broke down as he delivered the bad news to the workers gathered in the canteen. Production of the 380 would cease at the end of March, he told them, and 930 of them would lose their jobs. The executive’s emotion made an impression. “I don’t often see men cry,” says Carol Rollins.

“It was a bit like a funeral,” recalls press shop senior leader-trainer Andrew Coad. “Quite horrible, really.” For others, the news was almost welcome. “It’s like being around someone dying a long, slow, painful death,” says vehicle assembly group leader-trainer Scott Hann of the period leading up to the closure announcement. “It’s kind of a relief when it happens.”

There was a moment of utter silence. Unbelievably, the hush was broken by applause for McEniry. The anguish he had been through was plain to see, and the workforce seemed to have understood how hard it must have been. Some of them had known for years that the factory’s future was shaky. Quality assurance and production engineering manager Peter Angrave pinpoints the 2004 decision to kill the PS41L as crucial. “Some of us realised the possible outcome,” he says. Colleagues Mark Scott and quiet quality engineer Tony Nash, nod in agreement.

Others had hoped against hope that the 380 would at least serve out the term of its natural life, around five years. “There was all this talk about an agreement with the government about continuing in production until 2010,” recalls Peter Ryan, a section manager with the vehicle assembly group. Bob Ormsby agrees. “We all thought it would be about 2010.”

Others cite high petrol prices as the big problem. It certainly didn’t help that Hurricane Katrina blew into Louisiana across the oil-rig-studded Gulf of Mexico soon after the 380’s launch, causing fuel prices to spike all over the world. But with other big Australian-made cars continuing to sell at profitable volumes, and the ever-increasing popularity of SUVs, some at Tonsley Park dispute this view. Peter Angrave is one who doesn’t buy the theory that fuel prices alone killed the 380. “People just aren’t buying family-size cars so much these days.”

Some Tonsley Park workers believe the loss of the Magna range’s wagon, all-wheel-drive and LPG fuel options with the introduction of the 380 played a role. More frequently mentioned is the Australian market’s supposed dislike of the 380’s front-wheel-drive layout. Although many of the workers I meet are happy Magna or 380 owners, they suspect other car buyers are different. “You always hear that Australians don’t like front-wheel drive,” says grandmother of five Sally Forrestal, a leader-trainer in vehicle assembly.

Some Tonsley Park workers are more blunt. “Australians don’t seem to care too much about quality,” Chris Thompson says. “If quality sold, we’d still be in business.” A senior leader-trainer on the factory’s metalline, he has five children and is the family’s sole breadwinner. Thompson hasn’t found a new job, but will work on at Tonsley Park until December, part of a skeleton crew selected to stay on to make a stockpile of 280,000 spare parts for the 380 and earlier Magna models.

Thompson sees the closure of his workplace for the last 16 years as a loss to the nation, and it makes him angry. “I think Australia needs to take a good, hard look at itself,” he says. “We’re good at digging stuff up, and then buying it back when it’s been turned into something else, somewhere else.” Like Thompson, some other Tonsley Park workers are profoundly pessimistic about the future of Australia’s car industry.

“You’ll be doing the Ford story in three years time,” self-appointed press-shop jester Andrew Coad tells me. “I hope they survive, but … “

Others recognise the futility of their efforts to make the 380 a success, but take pride in how hard they tried. “We all wanted to give it our best go,” says Peter Angrave. “We all bought into the struggle.” Mark Scott points to a graph showing the factory’s own analysis of 380 quality, which improved rapidly after start of production and then held below the target fault rate with astonishingly little deviation from the very low average. “As you can see, we fought one hell of a battle.”

In return for the demands it made, Mitsubishi encouraged and invested in the training of Tonsley Park’s workforce. All of it. Peter Angrave, who started as a trade apprentice and gradually rose over 38 years to a senior management position, puts it succinctly. “The company has given us an education. It’s like a big university.” Angrave is certainly smart enough to see the big picture, and the threat to manufacturing industry in Australia that globalism poses. “The thing that really gets me is all the talk of a level playing field,” he says. How can Australia compete on equal terms with countries where our occupational health and safety, environmental and mandatory superannuation requirements don’t exist, he wonders.

Well trained and highly skilled, and arguably the best car makers in the country, there’s pride at Tonsley Park even as the day of defeat looms. Building cars is different, somehow, from other manufacturing industries, and MMAL’s workers know it. Robot programmer and press operator Greg Shephard will walk straight into a new job when Tonsley Park shuts. But he doesn’t think working for packaging company Amcor will provide the same problem-solving satisfaction as stamping out cars. “It’s only a box .. . “

Some of the older workers, like Bob Ormsby, Peter Ryan and Sally Forrestal, have decided they will look for part-time work. Others have decided to go into business for themselves. Tom Di Vittorio aims to launch a part-time fishing charter business with his brother, but has found a safety-net job at his old trade of panelbeating, too. Carol Rollins’ husband plans to set up a frozen-goods delivery round.

But the majority believe they’ll have to re-train. Some of the men are aiming to update their skills, or learn new ones. Trades are a popular choice, with several planning to begin mature-age apprenticeships. Bee Durbidge, too, is planning a career change. She thinks horticulture is a smart choice. “I want to get into something that’s not going to close down …”