Origins

The W12 engine can trace its genetics back to the Volkswagen VR6 unit which first saw the light of day in the 1991 B3 Passat and Corrado coupe. The VR name comes from “Verkürzt” and “Reihenmotor” meaning “shortened inline engine”.

The subtly retro-futuristic ute was named Surf-Out, designed with a unibody shape and, thanks to its skateboard platform, a deep tub for tools or eskies – as the job may require.

We reported at the time the Surf-Out might hint at a future successor to the Navara ute, which certainly live on diesel forever. But, in April this year, Nissan revealed another new electric concept with a wildly different look: the Arizon SUV, pictured below.

That got our mate Theottle the Photoshop wizard thinking that an edgier-looking electric Navara might be more suited to the segment.

Enter, what Theo calls the Arizona – a cleverly rugged twist on the Arizon’s name, particularly as Nissan has a test centre in the sizzling hot 48th state of the American union.

What do you think of the look? We know Kia and Hyundai will launch electric utes in the near future, and they’re likely to look pretty edgy in their own right. This so-called Arizona, what might otherwise be badged Navara or Frontier, could make for a sharp rival.

“We will consider technical application to the product for either E-Power (hybrid) or [fully-electric],” he told Australian media in March – mainly on the idea of adding E-Power hybrid tech to the Patrol and Navara in their next generation.

And while it appears likely that an E-Power hybrid version will join the range, an all-electric model is probably another generation away.

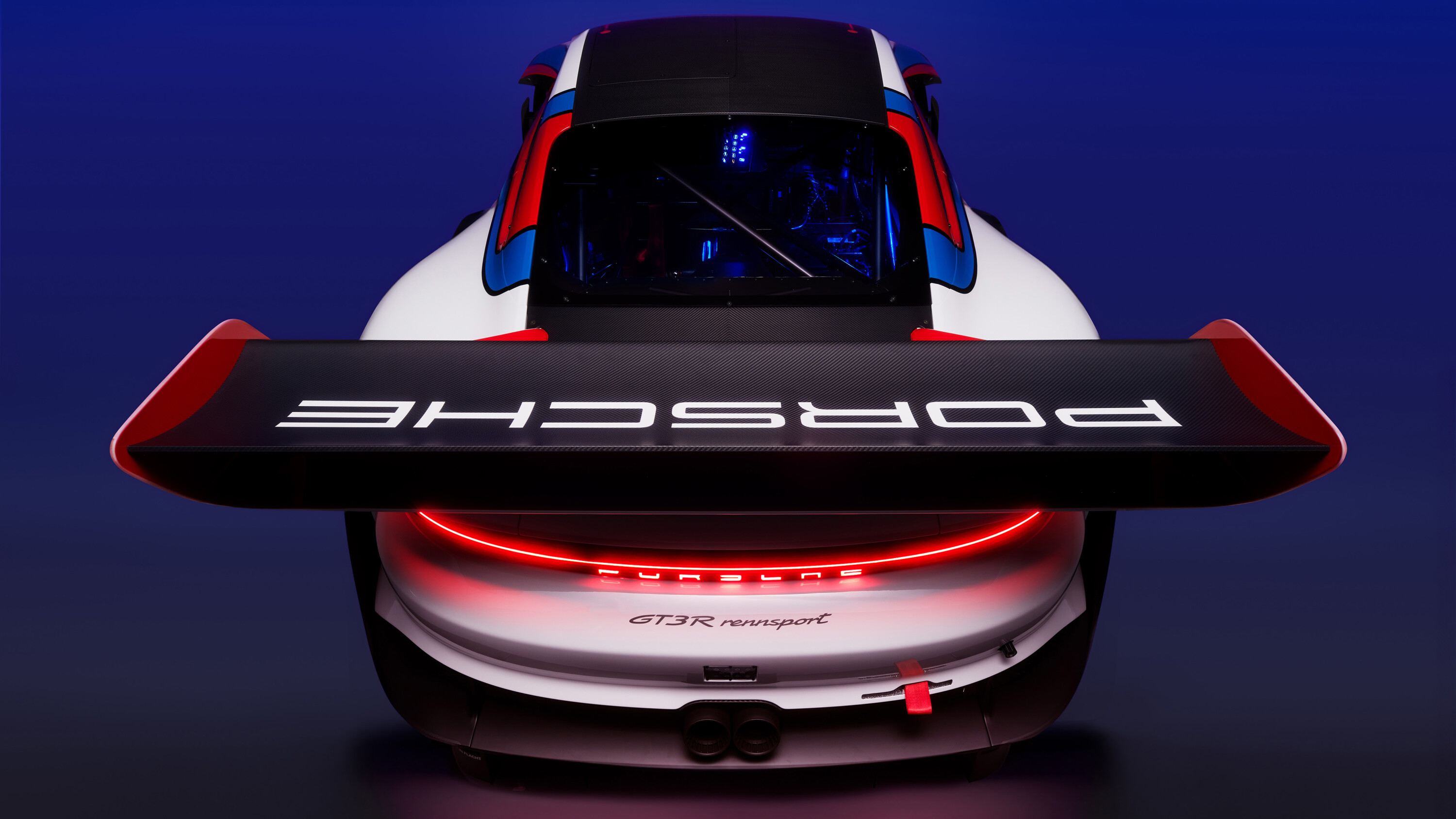

It’s not like Porsche’s catalogue needed a more aspirational model than the roadgoing 911 S/T, but that hasn’t stopped the German carmaker from churning out another wild variant of its iconic rear-engined sports car that “benefits technically from the freedoms that go beyond motorsport regulations”.

“The new Porsche 911 GT3 R Rennsport offers the experience of driving a nine-eleven-based racing car in what is probably the most primal form… it gives you goosebumps whenever you look at it and it combines the finest motorsport technology with a design language that is typical of Porsche”, said VP Porsche motorsport Thomas Laudenbach.

The GT3 R Rennsport will make its first in-anger appearance at Califonia’s Laguna Seca raceway during the Rennsport Reunion 7 festival, with 80,000 visitors expected between 28 September and 1 October.

Limited to 77 units, the 911 GT3 R Rennsport features a naturally aspirated 4.2-litre flat-six that redlines at a piercing 9400 rpm. And, without the GT3 series’ Balance of Performance (BoP) regulations, the Rennsport develops an extra 40kW (now 456kW) thanks to the use of E25 fuels and specifically developed pistons and camshafts.

Its six-speed sequential transmission runs the fourth, fifth and sixth ratios the racecar would in Daytona trim, though it gets a 20km/h top speed boost. The GT3 R Rennsport’s exhaust is uncorked as standard, though Porsche offers two quieter systems to play nice with noise restrictions.

As for aerodynamics, while the diffusers and flat floor are untouched, the carbon fibre bodywork has had a major overhaul. Only the roof and bonnet remain, with every other panel new for the Rennsport – the most obvious of which is the rear wing.

Porsche says the shape is inspired by the 1978 24 Hours of Daytona winning Brumos 935/77 racecar (we detect a hint of 993 Clubsport, too) and that it’s a functional aerodynamic piece, upping the Rensport’s total downforce compared to the road car.

A bespoke set of five-way adjustable dampers from KW Suspension offers further track-specific tuning available with replaceable shims. It also benefits from the same double-wishbone front suspension found on the racecar that’s finally made its way to the 992-generation 911 GT3 road car.

It wouldn’t be a Porsche RS model without some form of weight saving and showing Porsche’s excellence in the field, it’s managed to cut kilos out of a full-blown racecar. Titanium brake pad backings, a lighter 117-litre fuel tank and air-con delete should get it to the engineer’s ideal 1240kg kerb weight.

“We have given the limited edition model a little more width and have visually stretched the length, while at the same time it sits very low on beautifully designed wheels. This gives it perfect proportions and makes it look even more spectacular”, said Thorsten.

The team mentioned its similarities to the 2018 935 ‘Moby Dick’ reimagination based on a GT2 RS – though the GT3 R Rennsport has purer motorsport DNA.

Picking up a design feature from the 357 Concept, the Rennsport does away with physical mirrors in favour of a camera-based system that’s totally integrated into the bodywork.

Thorsten, Grant and the style team put plenty of effort into colour schemes, too. There are ‘ex-works’ paint schemes based on seven colours, while the pictured Rennsport Reunion design uses Porsche’s heritage colours and references the contours of Laguna Seca’s ‘Corkscrew’ set of corners.

Given the limited nature of the Rennsport’s production, expect it to command a premium over the ‘regular’ 911 GT3 which starts at around AU$840K (or €511,000). And to get one, you’ll need to be in Porsche’s good books.

Even with the introduction of vehicle safety technology not even dreamed at the turn of the century, young drivers continue to die on Australian roads at a greater rate than any other age group.

In 2021, people under 26 made up 14 per cent of all drivers on NSW roads yet represented almost a quarter of the state’s 275 road fatalities that year.

While there are many factors at play that contribute towards the sobering stats, a professor at UNSW believes that a return to good old-fashioned verbal and written communication could be a key to improving outcomes for young drivers.

Brett Molesworth (RPsych, PhD) is a Professor in Human Factors and Aviation Safety, and says his research shows that young drivers respond best to verbal feedback after completing a stint of driving either in a simulator or in the real world.

As part of a 13-year study, young drivers were assessed in a series of driving tests and provided with a summary of their driving behaviour in a verbal debriefing session.

“There’s adaptive technology in motor vehicles that provides you with an auditory alert when you exceed the speed limit,” Prof Molesworth said.

“But when we tested its effectiveness with young drivers, we were amazed to see it had the opposite effect with young drivers; ironically, they exceeded the speed limit even more.

“And when we asked them, ‘why didn’t you adhere to the speed limit when you heard that auditory warning?’, they basically told us they didn’t like ‘Big Brother’ observing them and telling them how to drive and what to do.”

Prof Molesworth’s team switched to post-test briefings with their young charges to explain how much they exceeded the limit by, and the implications of that action in both risk and monetary form.

When the young drivers received this debriefing via written feedback or an electronic device, they were less likely to adapt to the new learnings and curb their tendency to speed, according to Prof Molesworth.

“That information provided verbally seems to be the most effective way to reduce young drivers’ tendency to speed,” he said. “So they exceed the speed limit far less, and that lasts for up to six months, according to the latest research.”

One way that the research findings could have a real-world effect, according to the professor, is by including a verbal component as part of a young driver’s training while on their L plates.

“Every learner has a logbook where they record the hours they’ve driven, the conditions, the distance and whether it’s day or night driving,” he said.

“We would like a little section where they get feedback from their supervising driver – usually a parent or caregiver – that they then reflect on.

“In other words, self-evaluate their performance based on that feedback.”

Professor Molesworth will continue to study the notion of one-on-one feedback, as well as the ability of eye-tracking technology to observe where young drivers are looking while they’re driving.

One of his studies shows that young drivers infrequently looked at the speedometer while driving.

“We want to make sure that the focus on the speedometer is not detrimental to something outside the vehicle,” he said. “And we’d like to be able to come up with training that builds upon our verbal feedback about speeding that also takes into account hazard management.”

The 2023 i30 Active builds on this reputation, introducing refined aesthetics and enhanced features that aim to offer what are usually premium features as standard.

With a price-point between the brands light SUV the Venue and the slightly larger and recently face-lifted Hyundai Kona, the i30 is positioned as a premium specced hatchback.

At this price point, buyers are treated to an 8-inch touchscreen infotainment system, wireless Apple CarPlay & Android Auto, 16-inch alloy wheels, six speakers and cloth seats.

The hatchback Active is paired to a to a 120kW/203Nm 2.0-litre engine. The sedans 2.0-litre engine outputs 117kW and 191Nm and has the option of a manual transmission.

The entire range comes with Hyundai AutoLink Bluetooth system giving drivers some handy features through the app like the ability to monitor vehicle health, provide analytics and keep track of driving habits and fuel efficiency after every trip.

Standard features include 7 SRS airbags, a rear view camera, anti-lock braking system, hill-start assist and a tyre pressure monitoring system.

An optional Hyundai SmartSense safety feature pack (for about $1750) is available suite of including blind spot monitoring, lane keep assist, rear cross traffic alert and adaptive cruise control and more.

The Hyundai i30 is covered by a five-year/unlimited-kilometre warranty.

If you’re not needing a huge amount of space and want all the zippy capabilities of a smaller and more economical car the i30 could be your perfect companion.

Whether you’re navigating city streets or embarking on a weekend getaway, the i30 is ready to accompany you on your journey.

The Government of the United Kingdom will still require 80 per cent of carmakers’ sales to be electric by 2030, despite delaying the ban of new petrol and diesel vehicles last week.

The Tory government confirmed it won’t change its zero-emission vehicle mandate timeline to phase out internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles.

This means from next year, at least 22 per cent of carmakers’ total sales in Great Britain must be all-electric, which progressively rises annually to reach 100 per cent by 2035.

By 2030, 80 per cent of new cars and 70 per cent of new vans sold must be electric.

That’s despite prime minister Rishi Sunak announcing the relaxation of climate-related policies last week, including delaying the ban of new ICE vehicles by five years to 2035 in line with countries, such as France, Germany, and Sweden.

The move was criticised last week by carmakers that have already made investments to meet the 2030 target, with the manufacturers calling for more consistent public policy.

Locally, the Australian Government will soon introduce a ‘fuel efficiency standard’, which mandates a carbon emissions per kilometre cap on the average total sales of each car brand.

Like the United Kingdom’s approach, the Australian target will become stricter each year to boost electric and fuel-efficient vehicle sales in Australia.

The Government of the United Kingdom has delayed the sales ban of new internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles by five years to 2035.

At the UK prime minister’s speech overnight [The Guardian YouTube ↗], Rishi Sunak said the move is ‘easing the burden on working people’ by relaxing climate-related policies.

We’re aligning our approach with countries like… Australia

“I expect that by 2030, the vast majority of cars sold will be electric… People are already choosing electric vehicles to such an extent that we’re registering a new one every 60 seconds”, Sunak said.

“But I also think that, at least for now, it should be you the consumer that makes that choice, not government forcing you to do it.

“Because the upfront cost still is high – especially for families struggling with the cost of living – small businesses are worried about the practicalities, and we’ve got further to go to get the charging infrastructure truly nationwide.

“We’re aligning our approach with countries like Germany, France, Spain, Italy, Australia, Canada, Sweden, and [some] US states… and still ahead of the rest of America and other countries like New Zealand.”

Sunak’s move represents a relaxation to former Conservative Party prime minister Boris Johnson’s policy – announced in 2020 – which would have banned the sale of new pure petrol- and diesel-powered vehicles.

New plug-in hybrids will be allowed, and used traditional combustion engine vehicles can still be purchased after 2035.

The leader of the Conservative Party also echoed the European Commission’s recently-launched investigation into ‘artificially low’ made-in-China EVs.

“We need to strengthen our own auto industry, so we aren’t reliant on heavily subsidised, carbon-intensive imports from countries like China,” Sunak said.

The UK prime minister claimed it is already 48 per cent ahead of its Group of Seven (G7) partners – including Germany, Italy, France, Canada, Japan, and the United States – in achieving net zero emissions by 2050.

In Australia, Victoria recently ended its $3000 EV purchasing rebate and New South Wales will follow next year – both earlier than initially promised.

“This is the biggest industry transformation in over a century and the UK 2030 target is a vital catalyst to accelerate Ford into a cleaner future,” Brankin said.

“Our business needs three things from the UK government: ambition, commitment and consistency. A relaxation of 2030 would undermine all three.

“We need the policy focus trained on bolstering the EV market in the short term and supporting consumers while headwinds are strong: infrastructure remains immature, tariffs loom and cost-of-living is high.”

Meanwhile, a statement from the Volkswagen Group UK said despite the policy delay “we urgently need a clear and reliable regulatory framework which creates market certainty and consumer confidence, including binding targets for infrastructure rollout and incentives to ensure the direction of travel.”

Sunak has also extended the country’s deadline for installing heat pumps to 2035, alongside removing taxes on meat, aeroplane travel, and compulsory car sharing.

The Jeep Avenger electric SUV – due in Australia later in 2024 – is aimed at a more youthful audience, said its chief designer.

Jeep Europe’s head of design Daniele Calonaci said the Avenger had three design principles – young, fun and compact – to appeal to younger customers, with the brand also aiming to boost female ownership.

“Yes, it’s pretty intentional because as you can imagine, you know the average customer till some years ago for the Jeep were a male of 50 years,” said Calonaci.

“So, the deal was to put down the average age of the customer for Jeep and to have more young customers [and] also more female customers.”

“You know the Renegade, for example, reached the 20 per cent of female customers, but we are pushing to have the 40 per cent, for example, on the Avenger. We… [are] at that level in Europe. I think what we had in mind from the very beginning is already reality in Europe.”

However, Calonaci emphasised that the Avenger’s overall theme “is to have an active design”, rather than appealing to certain people, while conceding its “most compact size” could be an important consideration for a female customer.

Designed and engineered entirely in Italy, the Avenger is targeted at the European market and, excluding the iconic Willys Jeep, is the most compact Jeep ever at 4.08m long.

Despite its smaller dimensions, it retains classic design elements including a boxier shape, trapezoidal wheel arches, Jeep’s iconic seven-slot grille, and a high ground clearance, including a 700-millimetre tyre diameter said to be “pretty huge for this compact segment”.

The Avenger’s interior features a minimalistic layout prioritising easy cleaning with a “functional beam” inspired by the Wrangler, removable rubber mats for easier cleaning, a full-digital instrument cluster and a 10-inch infotainment system.

It also has a black moulded rear bumper to prevent scratches when stowing items like bicycles.

“We won’t sacrifice the space inside the car for the aerodynamics,” said Calonaci, highlighting the vehicle’s practicality, with 34 litres of front storage space and the 380-litre boot which, according to Jeep, can accommodate 2443 rubber ducks.

The 2025 Jeep Avenger electric SUV is due in Australia in the second half of next year with local details to be confirmed closer to its launch.

While a petrol Avenger, with a 1.2-litre turbo-three shared with the related Peugeot 2008, is available in certain markets, Jeep Australia has confirmed an electric-only stance for the Avenger – at least at launch.

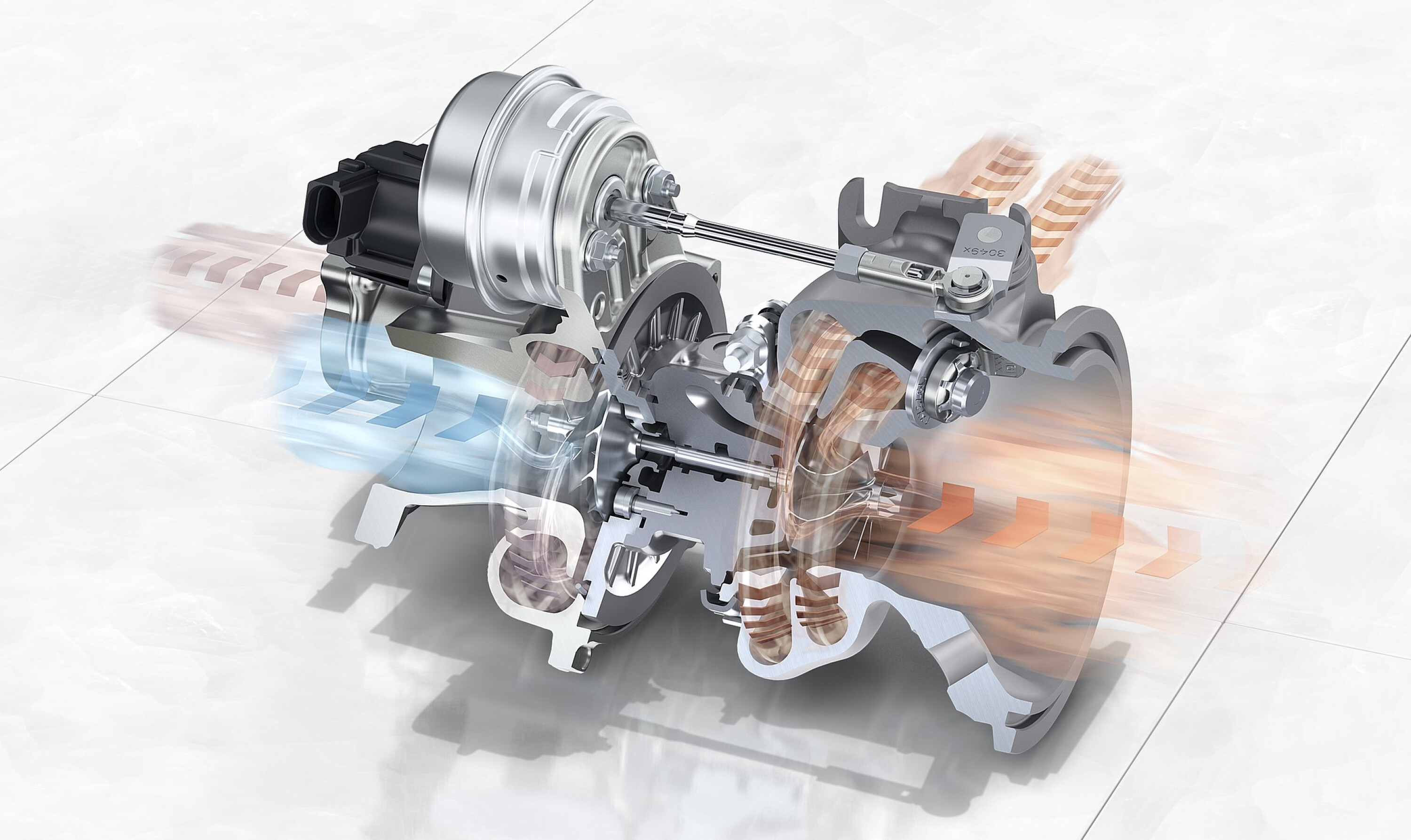

Well, this month we’ve tweaked things a little and wave auf wiedersehen to the Volkswagen Group’s W12 engine which is now found exclusively beneath the bonnet of Bentley’s upmarket wares.

Choose a flagship Continental GT or Bentayga and you’ll get six litres of 12-cylinder goodness, but you’ll need to be quick. The 12-pot engine is a rare breed now. Once the W12 bites the dust, only Aston Martin, Lamborghini and Rolls-Royce will take your order.

Ferrari? Well, the order books have closed on the 812 and, at the time of writing, for the four-seat Purosangue too.

It even featured in some Volkswagens, with Touaregs and Phaetons both having the W12 shoehorned in. That engine, effectively a pair of narrow-angle V6s sharing a common crankshaft, was very different to the one we’re used to in Bentley’s wares though.

For a start it made a mere 309kW without the benefit of forced induction and it required a bit of wringing, its peak torque of 550Nm available between 3750 and 4000rpm.

That was unacceptable to Bentley, who took over production of the W12 at its Crewe plant from Volkswagen’s factory in Salzgitter in Germany. By turbocharging the engine, changing the control systems, and fettling the cooling, injection and combustion processes, Bentley was able to bring the peak torque response of the engine down to 2000rpm in order to deliver the requisite effortless acceleration.

The W12 was always an engine that required careful compromises.

Bentley knew its flagship engine needed to have no more than 500cc per cylinder for emissions purposes, and the sub-5-metre dimensions of the original Continental GT sketches also meant it needed to be compact. The W12 fitted the bill perfectly. Ultimately it is Europe’s ever-tightening emissions regulations that have done it in.

Bentley has confirmed the W12 will be discontinued in April 2024 and that a few final build slots for Continental and Bentayga W12s are still available, but it’s about to get a very special send-off in the form of the limited-run Batur, another bespoke Mulliner vehicle that picks up where the Bacalar left off.

The 552kW Batur will see an 18-car production run, with the W12 being sent out the door in its most furious form yet. Another one bites the dust.

The W12 engine can trace its genetics back to the Volkswagen VR6 unit which first saw the light of day in the 1991 B3 Passat and Corrado coupe. The VR name comes from “Verkürzt” and “Reihenmotor” meaning “shortened inline engine”.

Unlike its V8 sibling, the W12 has never been able to utilise cylinder deactivation under partial load to save fuel. Put that down to the complexity of the W12’s crankshaft geometry. Balancing the engine and keeping the catalytic converters warm on the shut-down side is a technical problem that Crewe never managed to overcome. Here’s the kicker though.

We think we prefer the smaller engine.

The milestone was passed sometime last month, according to official registration data from the Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries (FCAI).

All-electric models made up 0.001 per cent of new car sales in 2010, but increased to 3.1 per cent share in 2022 and is currently sitting at 7.2 per cent so far in 2023 (to the end of August).

In the past few years, the number and choice of EVs has expanded in Australia from only a handful of mostly high-end, six-figure priced offerings to more than 50 individual models today, priced from just below $40K before on-road costs, with a rise in Chinese-made EVs getting us there. (China has a strong competitive advantage with cheaper labour and a more local supply for battery packs.)

Yet, the local EV market has been dominated by relatively recent entrants.

These made-in-China models have quickly shaded the venerable older EVs that are still on sale today, including the Nissan Leaf small hatchback (2460) and Jaguar I-Pace luxury crossover (355).

Both European-made EVs were introduced locally in 2012 and 2018 respectively.

Our EV market is now seasoned enough to have even seen a number of models retired or discontinued, including the Mitsubishi I-MiEV, Renault Zoe, BMW i3, Hyundai Ioniq Electric, and more recently the Tesla Model S and Model X.

Sales are projected to rise further with forthcoming carbon emissions standards that aim to boost supply, despite some arguments otherwise.

Public charging infrastructure is also growing in locations and reliability to meet increasing demand, while EV incentives have been introduced and some have been pulled back earlier than promised.

Since 2010, more than 18,158 plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) and 55 hydrogen electric models have also been registered.

It’s worth noting Tesla only started officially reporting registration data from 2021 and there was a delay in posting BYD Atto 3 sales figures, with two months worth of data unrecorded after its September 2023 launch.

FCAI guidelines also improved in 2020 to record more realistic sales numbers. The peak automotive body started cross-checking registration data in order to limit the loophole of some dealers erroneously reporting a vehicle as sold.

Some dealer demonstrators may still be counted if they are registered.

In 2019, the FCAI also combined EV and PHEV sales together.

| Year | No. of EVs registered | Market share |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 112 | 0.001% |

| 2011 | 49 | 0.005% |

| 2012 | 253 | 0.02% |

| 2013 | 292 | 0.03% |

| 2014 | 1135 | 0.10% |

| 2015 | 1108 | 0.10% |

| 2016 | 219 | 0.02% |

| 2017 | 1124 | 0.09% |

| 2018 | 1352 | 0.11% |

| 2019 | 2925* | 0.28%* |

| 2020 | 1769 | 0.19% |

| 2021 | 5149 | 0.49% |

| 2022 | 33,410 | 3.09% |

| 2023 (to end August) | 56,922 | 7.22% |

| Totals | 105,819 | |

| *Note: In 2019, the FCAI combined pure electric and PHEV sales together. | ||

Our original story continues unchanged below.

Australia is on track to have more than 100,000 electric vehicles on the roads this year, according to research by the Electric Vehicle Council (EVC).

The lobby group reveals an estimated 83,000 electrified cars are currently in circulation – almost double last year’s total – comprised of 79 per cent full battery-electric vehicles (BEVs) and 21 per cent plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs).

BEVs and PHEVs made up 3.8 per cent of the new car market share in 2022.

These figures, however, exclude imported used examples from overseas, which has been an increasingly popular method for EVs to obtain lower prices.

“If you think you’re seeing more EVs on the road than you used to, you’re right, but if we want to hit our national emissions targets we won’t make it on this current trajectory,” EVC CEO Behyad Jafari said.

“To achieve the Federal Government’s emission target we’ll need a near fully zero-emission vehicle fleet by 2050… that means reaching one million EVs by 2027 and around three million by 2030.

“We can definitely hit these goals, but not without an ambitious fuel efficiency standard to expand the supply of EVs to Australia.”

The Council also outlines that 1530 more public EV charging stations came online in 2022.

Of the 3413 total public chargers in Australia, 134 of them are fast chargers (classified as outputting 24 to 99kW DC) and 99 are ultra-rapid stations (100kW DC or more).

The Australian BEV market is moving at a steady pace, selling 33,410 units last year. It was spearheaded by the Chinese-made trio – the Tesla Model 3 sedan, Model Y SUV, and BYD Atto 3 crossover in 2022.

Volvo Cars Australia has already committed to selling an EV-only line-up by 2026, while the Australian Capital Territory is set to ban the sales of new internal combustion petrol and diesel engine cars from 2035 – following in the footsteps of Europe and the United Kingdom.

However, at this stage, Australia lacks tough average tailpipe emissions regulations, such as the impending Euro 7, which pushes carmakers to offer more low- or zero-emissions vehicles – otherwise heavy financial penalties apply.

It’s also no secret that hydrogen fuel-cells have long been used as an excuse for governments and lobbyists to delay vehicle carbon emissions restrictions, while hydrogen combustion engines and synthetic fuels have also been mooted as options to keep the traditional engine alive where battery EVs aren’t suitable.

The question remains: which alternative fuel – BEVs or FCEVs – is ultimately best for buyers, the market and the planet?

Almost every major manufacturer now has a BEV in the market or on the way, and nearly every newly-founded car brand is devoted to BEVs only.

Tesla and Build Your Dreams (BYD) have rapidly grown globally in just a few years, while carmakers such as the Hyundai Motor Group, Volkswagen Group, BMW Group, Geely, and now the Toyota Motor Corporation are rolling out their BEV offerings locally.

In contrast, only two carmakers lease a new production hydrogen vehicle in Australia today – albeit for a limited number of commercial fleet buyers only: the second-generation Toyota Mirai sedan and the Hyundai Nexo SUV.

Then, there’s the question of public recharging or refuelling infrastructure… For more, read on.

It appears carmakers generally favour BEVs, but are still playing with the potential of FCEVs in the transportation sector.

Toyota in particular has been vocal in committing to offer a variety of powertrains – including petrol, diesel, BEV and FCEVs – so buyers can choose the right one for their driving needs depending on the country, yet has vowed to prioritise BEVs.

BMW is developing the iX5 Hydrogen SUV, which will also share its powertrain with the upcoming Ineos Grenadier FCEV. Others such as Hyundai, Honda, Renault and Geely are also dipping into exploring hydrogen-powered cars.

However, Kia Australia has put distance between itself and corporate sibling Hyundai – with the view that battery-electric tech is rapidly approaching the point where hydrogen will only have very few advantages.

| BEV advantages | BEV disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Will achieve price parity with combustion-engined cars in five to 10 years (if not already today) | Generally, the higher price will remain a barrier for many |

| Already provides more than enough range for the average Australian driver (30km to 40km per day) | If you regularly drive long distances, a hybrid or PHEV may be more suitable |

| More entry-level models use LFP cathodes, which is cobalt-free, thermally safer, and longer lasting | Use of raw materials, such as lithium and cobalt, is environmentally contentious u2013 and perceived concerns remain around safety and longevity |

| Home/work electricity is still cheap compared to petrol and diesel u2013 despite rising costs | Public charging can be expensive depending on the network, location and even time-of-day |

| Using solar energy and battery storage systems means free and sustainable recharging at home or work | Australiau2019s electricity grid is mostly from coal u2013 but renewables are growing market share |

| Public charging stations are quickly expanding across Australia and improving reliability | Public charging stations can be unreliable and out-of-order at times, with not enough locations available nationwide (for now) |

| EV model DC charging speeds are getting faster, resulting in reduced waiting times (30 minutes or less) | Most faster charging EVs are pricier to buy and youu2019ll often need to choose a pricier ultra-rapid charging station |

| Instant electric power, regen and engine-free quietness makes driving easy | BEVs are generally heavier due to the large battery pack |

But, the inherent advantages of battery-electric vehicles are quickly outweighing the negatives – and they’re already more than sufficient for most Australians’ needs today.

While there are still barriers around the typically higher purchase price, a number of BEV models have already achieved price parity – such as the BYD Dolphin, Atto 3, MG 4 and Tesla Model 3 – as the cost to enter into a petrol- or diesel-powered car continues to rise.

With most Australians living in urban or suburban areas, BEV driving ranges are already at the point where the average commuter would never need to stop at a public charging station, simply by trickle-charging at home overnight (or only once every week or two if reliant on public infrastructure).

And, despite the higher initial environmental footprint, BEVs are still more environmentally sustainable over time, with renewable electricity sources already making up around 35.9 per cent of Australia’s grid in 2022 – and improving, according to the Clean Energy Council [PDF ↗].

However, there are still valid concerns around safety if batteries catch fire and cause a thermal runaway reaction. Despite more entry-level EVs using the lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) battery cathode that reduces this risk, typical energy-dense lithium-ion type batteries will remain in most models for years to come.

There are also limitations around the number and reliability of public charging stations, and current BEV driving range may not be enough if you live in regional and rural areas. Therefore, regular long-distance drivers are better off with a traditional hybrid or plug-in hybrid instead (for now) as a better alternative over pure diesel.

| FCEV advantages | FCEV disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Familiar and quick filling up process | Almost non-existent public hydrogen refuelling stations in Australia |

| Zero exhaust emissions (besides water), electric-only driving benefits | Most hydrogen today is not eco-friendly in production, true u2018green hydrogenu2019 requires a complex process of carbon capture and intensive use of renewable energy |

| No contentious large battery required | Up to 50 per cent less efficient drivetrain than BEVs to power the wheels |

| Typically longer driving range than BEVs | Hydrogen molecules can permeate away when parked, BEVs are quickly increasing range capabilities |

| Safer than petrol- and diesel-engine vehicles, despite high-pressure hydrogen tanks | Significantly more expensive to buy than BEVs, no models publicly available |

With the same local zero-emissions promise as BEVs, most FCEVs can refill within five minutes via a high-pressure pump – but stations do need to pause and take time to repressurise at times. It also uses a tiny traditional hybrid-sized battery, so it doesn’t require as many controversial raw materials as full BEVs.

Hydrogen-powered cars also provide slightly more driving range with better energy density than batteries and fuel – one kilogram of hydrogen contains about 3.4 times the energy of 1kg of petrol. For example, the Hyundai Ioniq 5 BEV offers up to 507km claimed WLTP driving range, whereas the Nexo FCEV has up to 666km.

However, while FCEVs might provide a more familiar transition from an internal combustion engine vehicle, the two models that are in Australia aren’t available to the general public (for now). Instead, they’re limited to select commercial customers (mostly government fleets) – and Toyota and Hyundai are only willing to provide a limited-time trial lease to them.

Exacerbating this, if BEVs are considered pricey, hydrogen cars are even expensive. For example, the Toyota Mirai FCEV costs $63,000 on just a three-year / 60,000km loan – with a full ownership cost for the Camry-sized sedan priced beyond $100,000 overseas.

While BEVs can use any three-pin power socket, hydrogen cars depend solely on public refuelling infrastructure. Yet, it’s almost non-existent in Australia today, with only four publicly accessible stations nationwide – in Canberra (ActewAGL), Melbourne (Toyota and CSIRO), and Brisbane (BP).

Even with them installed, the costs to run each refuelling station are more staggering than BEV charging stations, since hydrogen requires special storage, needing to be contained either at high pressure or extremely low temperatures.

A true ‘green hydrogen’ process will require the entire production chain to be powered by renewable energy – but it still requires a lot of power and wasted energy to compress the gas to a pressure where it contains enough energy to drive a vehicle.

A battery-electric car can be charged up directly (via a built-in inverter if by AC power) from the grid or solar electricity and then discharge stored energy via its motors for driving.

By contrast, the hydrogen method would use that same electrical energy to convert water into hydrogen, expend more energy to compress the gas for transportation, then use more energy to distribute and pump it into a car, where a fuel cell stack then converts the hydrogen back into electricity for the motor.

That’s compared to BEVs, which would only have around 20 per cent of overall losses through the grid-to-car-to-wheels process.

In short, there’s a lot of indirect and circling around processes – when ultimately a hydrogen vehicle just needs pure electricity to drive.

There still may be a place for hydrogen tech in commercial applications, such as long-haul trucks, where stopping to charge isn’t feasible for businesses.

But, for now, regional motorists and regular road-trippers would be better served by combustion-engined petrol-electric hybrid cars or plug-in hybrids as a more suitable alternative to pure diesel.

The ‘chicken and egg’ issue that is only just now being overcome with BEVs is even more prevalent with FCEVs.

While some politicians and lobbyists (mostly oil companies) continue to occasionally spruik a hydrogen-powered utopia, the current state of FCEVs is similar to BEVs from more than a decade ago – with an inefficient production process, drivetrain and expensive price barrier.

On the other hand, BEV tech is quickly evolving to provide longer driving range, better energy efficiency, faster charging, improved safety and longevity, and better environmental sustainability in the production process – just to name a few.

There may still be a place for hydrogen in our transportation sector for some applications, but BEVs are already sufficient for most Australians’ needs and are set to become the main choice of power in the coming years.

Wheels Media thanks Tony O’Kane for the original version of this story.

On the plus side, LFP doesn’t use contentious cobalt and nickel materials, making them around 20 per cent cheaper than regular lithium-ion nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) packs, according to BloombergNEF [↗].

Yet, LFP batteries were still hit by a 27 per cent price rise in 2022 compared to 2021 – where demand overtook supply for the first time.

While some automakers and the International Energy Agency [↗] have said market costs started to lower again in 2023, BloombergNEF [↗] expected it to start dropping in 2024 as more extraction and refining facilities open – in addition to developing better recycling processes.

Mercedes-Benz chief executive Ola Källenius told Reuters [↗] that EVs will remain more expensive “for the foreseeable future” due to varying costs in battery raw materials, software development and electricity prices – despite targeting a ‘significant cost reduction’ for the forthcoming CLA electric sedan and using LFP for entry variants.

But, they aren’t expected to come to market until at least 2025 – and it’ll be even longer before they’re a properly affordable proposition.

In the interim, MG’s director of battery development, Ge Hailong, told WhichCar that it’s developing a half solid-lithium hybrid pack to debut in 2025 that’s even cheaper and longer-lasting than LFP.

Meanwhile, some major carmakers including Hyundai, Toyota and BMW have also invested in developing hydrogen fuel-cell powertrains – which has its own benefits, but is still significantly less efficient to produce and drive an EV than pure battery.

| EV battery material makeup | Sodium-ion (Na-ion) | Lithium-ion (Li-ion) |

|---|---|---|

| Cathode (positive terminal) | Sodium | Lithium |

| Electrolyte (separator) | Sodium | Lithium |

| Anode (negative terminal) | Hard carbon | Graphite |

| Current collector (outside each cathode/anode electrode) | Aluminium | Aluminium (for cathode), copper (for anode) |

Sodium-ion cells share a similar construction and alkali metal properties with Li-ion, albeit being slightly heavier and bigger.

The anode’s hard carbon material allows a broader range of available electrolytes, resulting in a wider operating temperature range and ultimately makes it safer to use (more on that below).

| Sodium-ion (Na-ion) | Lithium-ion (Li-ion) | |

|---|---|---|

| Energy density | u223c100-150Wh/kg (potential for 200Wh/kg+) | u223c150Wh/kg for LFP, up to 275Wh/kg for NMC cathodes |

| Battery pack cost | N/A u2013 expected to be 20% to 40% cheaper than Li-ion | u223cAU$220 per kWh (2022 average) |

| Operating temperature | -30 to 60u00b0C | 15 to 35u00b0C |

| Safety | Lower thermal runaway risk; can be transported with no risk as it can be fully discharged | Thermal runway risk (but lower for LFP cathode); cannot be under 30% during transportation |

| Recyclability | Less raw materials included; simpler recovery process | Separating metals needed; more complex process |

Note: Data collated from C&EN research, BloombergNEF, Faradion, pv magazine, Digitimes Asia, Ecotreelithium, and the International Energy Agency.

Critically, sodium-ion tech lacks expensive raw and environmentally unsustainable materials such as lithium, cobalt, copper and graphite – which are in short supply due to slow mining processes not keeping up with the increasingly strong demand.

For the world’s largest EV battery maker, Contemporary Amperex Technology (CATL), it claims its sodium-ion pack provides similar safety and longevity to LFP, with faster charging capabilities and better low temperature performance – but is less energy dense (i.e. less driving range), at least in first-generation form.

Sodium-ion battery producer Faradion [↗] claims the electrolytes are more stable than lithium-ion, and its own testing demonstrates no fire reaction when penetrated with a nail.

That’s similar to BYD’s LFP Blade Battery claims, but according to the British company, sodium-ion still outputs significantly less heat.

When completely discharged (at zero volts), its peer-reviewed research [↗] demonstrates the risk of thermal runaway from short-circuiting is eliminated – which is ideal for transporting EVs in cargo ships en masse, for example.

Cheaper manufacturing costs and the initially lower energy density than LFP means they’ll be found on more affordable, entry-level models with shorter driving ranges.

Chinese automaker BYD intends to introduce sodium-ion tech on its Seagull micro electric car soon in a cheaper base variant, but it’s only sold in China for now.

Similar to BYD, CATL has already released its own Na-ion batteries in 2021 and plans to ramp up production this year to debut in a Chinese-market Chery EV. But, it may initially take a hybrid sodium-lithium approach, according to local media reports (via Electrive [↗]).

British startup Faradion has been developing sodium-ion batteries since its inception in 2011. Its batteries are already in production, with the first commercial energy storage battery installed in Australia in late 2022.

While lithium-ion battery prices have increased, sodium-ion packs have emerged as the new solution to reduce manufacturing costs, rely less on environmentally unsustainable raw materials – a further reduction from LFP – and offer better thermal safety to ultimately lower the cost barrier to electric vehicle adoption and address contentious issues.

Despite this, if it does reach the masses, it may take some time with most major automakers still favouring LFP today for entry-level EVs – especially in China, where the majority of LFP packs are manufactured (according to Asia Financial [↗]).