It must be one of the loneliest graves in Australia, hidden by the travesty of history, the remoteness of the Australian inland and the vastness of one of the biggest privately-owned cattle properties in the Outback. And to get there isn’t a walk in the park, with our Patrol stirring up the deep bulldust which billowed behind us like a heavy, dark smothering cloak of fine grey powder.

The track we were following was more a set of cowpats than a 4WD route across the flat, dry black-soil plains, and none of the tracks shown on either of our GPS units had any similarity to the tracks on the ground.

That was probably not surprising as we were on the floodplain of the Bulloo River in southwest Queensland, and any track lasts only as long as the next silt-laden flood oozes down this outback river. We came to a dam or turkey nest tank, its high banks a marker looking more like a small mesa on these flat lands.

Here amongst the churned-up dust of a few thousand cattle, most of whom were milling around us, we lost the track completely.

Here amongst the churned-up dust of a few thousand cattle, most of whom were milling around us, we lost the track completely.

We circled the enclosed water point a few hundred metres out from the tank, bumping across the crab-hole country, before picking up the track once more, this time heading east to the distant tree-line of the main channel of the Bulloo River.

We had received permission from Bulloo Downs Station to visit the grave of Dr Ludwig Becker, one of the scientists and the artist of the Burke and Wills (B&W) 1860-61 expeditions, and now we were trying to find this lonely grave.

In fact, two other members of that fateful expedition are buried here as well – Charles Stone and William Purcell – and all had died from the effects of scurvy and the privations they had suffered in this lonely place.

In fact, two other members of that fateful expedition are buried here as well – Charles Stone and William Purcell – and all had died from the effects of scurvy and the privations they had suffered in this lonely place.

All had been part of the ‘Supply Party’ that had been told to follow Burke’s main party up to Cooper Creek from Menindee, but this slower moving band of men and animals had struck difficult times and had been relegated to a forgotten sideline in Australian history.

For our visit we had first phoned the manager and then visited the homestead and, after receiving a briefing on ‘biosecurity measures’ that we needed to follow (as well as nearly being attacked and eaten by a bloody big pig dog), we were given a rough mud map and directions to the grave. But, like most mud maps which make perfect sense to the person who drew them, you need to take them with a grain of salt and add a bit of intuitive guesswork and luck to make them work.

On the ground our route swung north then back to the east, where we floundered amongst some lignum scrub before we picked up the main track once more and turned south for the final bumpy drive to the Koorliatto Waterhole.

On the ground our route swung north then back to the east, where we floundered amongst some lignum scrub before we picked up the main track once more and turned south for the final bumpy drive to the Koorliatto Waterhole.

On the edge of this long, muddy stretch of water the Supply Party became trapped here for around a month in March/April 1861, only moving on when warlike Aboriginal bands began harassing them.

Today, a small fenced grave lies a short distance from the waterhole beside the trees that line the riverbank, while the barricade the explorers had built for their protection from Aboriginal attack, sadly, there is no sign of it. It’s a lonely, isolated spot rarely visited by anyone, but we were happy we had made the effort.

After checking out the nearby drying waterhole, well down from its maximum level but still with a lot of water in it, we backtracked to our camp on the Bulloo – near where today’s main dirt road crosses the channel – and watched the sun sink into oblivion.

After checking out the nearby drying waterhole, well down from its maximum level but still with a lot of water in it, we backtracked to our camp on the Bulloo – near where today’s main dirt road crosses the channel – and watched the sun sink into oblivion.

We had left Melbourne a couple of weeks previously and had battled wet, slippery dirt roads for much of our time through north-central Victoria and across the border into NSW.

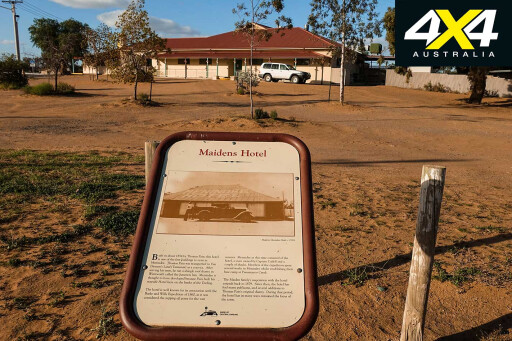

From Balranald we took the old Prungle Mail Road before skirting alongside the Darling River to Pooncarie and on to Menindee, which was the first town on the Darling and the oldest European settlement in western NSW. Of course, the town has a couple of pubs, the most famous being the Maidens Hotel, where ol’ Burke ensconced himself for a few days while splitting his expedition.

The rest of Burke’s party were camped at Pamamaroo Creek, near the lake of the same name, well away from the attractions and vices of the hotel. We camped out at the lake as well, where there are dozens of spots along the water’s edge to enjoy; but with today’s speed of transport we slipped back into the Maidens for a beer and a meal one night.

The rest of Burke’s party were camped at Pamamaroo Creek, near the lake of the same name, well away from the attractions and vices of the hotel. We camped out at the lake as well, where there are dozens of spots along the water’s edge to enjoy; but with today’s speed of transport we slipped back into the Maidens for a beer and a meal one night.

At Menindee, the grave of one of the Burke and Wills cameleers can be found.

Dost Mahomet had been recruited by George Landells when he was organising camels from India for the expedition. Mahomet and three other camel handlers had accompanied B&W from Melbourne, and Mahomet had gone to Cooper Creek and the depot there with the main party.

Returning from the Dig Tree with Brahe (who’d been in charge of the Depot Camp at the Dig Tree), Mahomet had stayed at Menindee looking after the camels and equipment that William Wright had also brought back from Koorliatto Waterhole to the Pamamaroo Depot.

Returning from the Dig Tree with Brahe (who’d been in charge of the Depot Camp at the Dig Tree), Mahomet had stayed at Menindee looking after the camels and equipment that William Wright had also brought back from Koorliatto Waterhole to the Pamamaroo Depot.

Alfred Howitt, in charge of the search party sent out by the Victorians to find B&W, had reached Menindee in early January 1862, and, just a couple of days later, one of the bull camels attacked Mahomet, where he lost the use of his arm, which effectively disabled him for life.

Mahomet appealed to the Victorian government for compensation but was only ever paid £200 (about $20,000 in today’s money). He returned to Menindee and worked in the local bakery and, when he died in 1881, he was buried just out of town where he used to pray each day.

Today his grave lies beside the Broken Hill road just a short distance from the centre of Menindee, and in 2006 the local shire restored the headstone and fence around the gravesite.

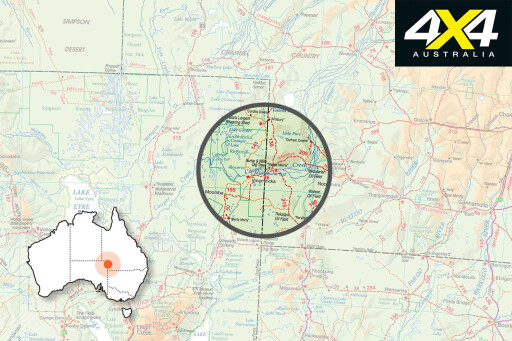

From Menindee we headed north and, from Tibooburra, we again took a lesser-used route and headed up via Wompah Gate through the famous Dog Fence, where we crossed the border into Queensland; then we turned east along the Thargomindah Road to our subsequent search for Becker’s grave. After swinging through Thargomindah and turning west we stopped at the Noccundra Pub, camping down on the waterhole of the Wilson River.

From Menindee we headed north and, from Tibooburra, we again took a lesser-used route and headed up via Wompah Gate through the famous Dog Fence, where we crossed the border into Queensland; then we turned east along the Thargomindah Road to our subsequent search for Becker’s grave. After swinging through Thargomindah and turning west we stopped at the Noccundra Pub, camping down on the waterhole of the Wilson River.

From there we headed to the Cooper Creek and on its northern bank we stopped at the famous Dig Tree, where much of the drama of the B&W expedition played out. You probably know the story of what happened here – if you don’t, have a read of the book by the late Sarah Murgatroyd, The Dig Tree. In amongst the plethora of books by numerous people over the 150-odd years since the expedition, this is one of the best and most readable.

We then headed for Innamincka and camped on the Cooper on the ‘town common’ in the shade of some tall old red gums, making sure we weren’t too close to any overhanging branches. This is a top spot to camp whatever you enjoy about inland Australia, and everyone should come to this idyllic stretch of water sometime in their life.

We then headed for Innamincka and camped on the Cooper on the ‘town common’ in the shade of some tall old red gums, making sure we weren’t too close to any overhanging branches. This is a top spot to camp whatever you enjoy about inland Australia, and everyone should come to this idyllic stretch of water sometime in their life.

Of course, the Innamincka pub is a mighty fine attraction and always a top spot for a coldie and a meal, especially on a Sunday night when the weekly roast is on the menu. If you are into the B&W saga, though, then there is no more important place to visit.

Spend a few days wandering the creek, not only visiting the Dig Tree but also checking on the places where Burke and Wills both died. It’s also here where John King, the sole survivor of the party that reached the Gulf, was found.

While Will’s grave site and the spot where King was discovered are downstream from the small township, Burke’s grave is east of the town beside a waterhole just downstream from Cullyamurra Waterhole, one of the longest and deepest stretches of water to be found anywhere on our inland. Most of the time the tracks to these sites are graded and very dusty, but when heavy rain is in the area or the Cooper floods then the access tracks get closed off.

While Will’s grave site and the spot where King was discovered are downstream from the small township, Burke’s grave is east of the town beside a waterhole just downstream from Cullyamurra Waterhole, one of the longest and deepest stretches of water to be found anywhere on our inland. Most of the time the tracks to these sites are graded and very dusty, but when heavy rain is in the area or the Cooper floods then the access tracks get closed off.

The bodies of the explorers and the survivor, King, were found in September 1861 by the relief party led by Howitt. Howitt had buried the bodies of Wills and Burke and then returned to Melbourne, but he was back on the Cooper in February 1862, tasked with the job of recovering the bodies of B&W and taking them back to Melbourne.

Charlie Grey, who was the fourth member of the small party that crossed the continent to the Gulf, lies buried somewhere near or at Lake Massacre, west of Innamincka and south of the track that leads to Coongie Lakes.

There’s quite a bit of conjecture about Charlie’s final resting spot, but there is a plaque on a steel post at Lake Massacre, near where a tree blazed by the explorer John McKinlay was discovered. McKinlay had been sent out by the South Australian colony to search for the B&W party in late October 1861 and had found the grave of a European here; possibly Grey’s. McKinlay, fearing the worse, gave the dry lake the ‘Lake Massacre’ moniker.

There’s quite a bit of conjecture about Charlie’s final resting spot, but there is a plaque on a steel post at Lake Massacre, near where a tree blazed by the explorer John McKinlay was discovered. McKinlay had been sent out by the South Australian colony to search for the B&W party in late October 1861 and had found the grave of a European here; possibly Grey’s. McKinlay, fearing the worse, gave the dry lake the ‘Lake Massacre’ moniker.

We have been to this lonely site a couple of times over the years, but if there is a grave here it is hard to find. Sometime in the 1950s or early ’60s, Alex Towner, an early B&W devotee, had erected a sign close to the northern end of the lake on a tall steel pole, while a friend of mine, the late Roger Collier, believed he found the grave and the tree blazed by McKinlay that marked the site of the burial, in 1983; others aren’t so sure!

We went back together in 1993 (see 4X4 Australia October 1993 issue) and found the sites again, but on our most recent visit a few years ago we found neither the tree or the sign. You need special permission of the local station and the NP&WS (National Parks and Wildlife Service) to get to here and, while there are no obvious tracks to the lake, a fence line will get you close to the southern shores of the ephemeral lagoon.

We went back together in 1993 (see 4X4 Australia October 1993 issue) and found the sites again, but on our most recent visit a few years ago we found neither the tree or the sign. You need special permission of the local station and the NP&WS (National Parks and Wildlife Service) to get to here and, while there are no obvious tracks to the lake, a fence line will get you close to the southern shores of the ephemeral lagoon.

From Innamincka we headed north to the Gulf, where there is one other grave associated with the B&W expedition. But you can’t come this far when you have an interest in the B&W expedition and not take the short diversion to B&W Camp 119 on the edge of the Bynoe River.

This was B&W most northerly camp and the one where leader Burke and his young 2IC, Wills, walked to and reached the Gulf; although, because of the mangroves, they couldn’t see the sea.

This was B&W most northerly camp and the one where leader Burke and his young 2IC, Wills, walked to and reached the Gulf; although, because of the mangroves, they couldn’t see the sea.

While that was a bit of a bugger for them, today it is easy and we had headed to Normanton and then Karumba to enjoy a view of the ocean and the setting sun – a magical moment in our crossing of the continent. The ill-fated explorers turned south from here and headed back to their depot at Cooper Creek, walking into the history books ... not as the most successful explorers Australia has seen, but certainly the best known.

The last and most northerly camp of B&W was discovered by Frederick Walker, who was the leader of one of the two parties sent out by the Queensland colony at the time.

Walker had gained a pretty notorious reputation while in charge of the Native Mounted Police in Queensland during the 1850s, but he was a good, tough bushman.

Leaving Rockhampton in August 1861 he headed for the Gulf, where he rendezvoused with Captain Norman of the HMCSS Victoria, which had also been sent out by the Victorians to look for B&W. Walker discovered traces of the B&W expedition on the Flinders River, as well as their most northerly camp on the Bynoe River where he blazed a tree and mapped the site.

Leaving Rockhampton in August 1861 he headed for the Gulf, where he rendezvoused with Captain Norman of the HMCSS Victoria, which had also been sent out by the Victorians to look for B&W. Walker discovered traces of the B&W expedition on the Flinders River, as well as their most northerly camp on the Bynoe River where he blazed a tree and mapped the site.

He later went on to survey the route of the telegraph line that came ashore at Burketown. While here he caught blackwater fever, dying a few days later in 1866, not far from the homestead of Floraville Station, close to the falls on the Leichhardt River.

We continued westward from Camp 119 and camped on the Leichhardt River near the falls of the same name. There was hardly a trickle of water over them; although, large pools lay at the base of the now dry cliffs.

Close by is the grave of Frederick Walker, and the station allows access to the site. We took the main track into the homestead and then, a few hundred metres before the main buildings on the property, swung left onto a graded track which led a short distance to Walker’s final resting spot.

Close by is the grave of Frederick Walker, and the station allows access to the site. We took the main track into the homestead and then, a few hundred metres before the main buildings on the property, swung left onto a graded track which led a short distance to Walker’s final resting spot.

We paid our respects and, with our enjoyable travels in finding the graves of these early brave pioneers over, reluctantly turned south; but that’s another story for another time.

Travel Planner

Travel Planner Following Burke & Wills Across Australia by Dave Phoenix is a great guide if you want to follow the explorers. To find out more and for the latest info regarding the Burke and Wills expedition, check out: burkeandwills.net.au The best maps for a dirt-road journey across the continent are Hema Maps’ Outback NSW, Outback Qld and the Top End & Gulf Country maps.

Travel Planner Following Burke & Wills Across Australia by Dave Phoenix is a great guide if you want to follow the explorers. To find out more and for the latest info regarding the Burke and Wills expedition, check out: burkeandwills.net.au The best maps for a dirt-road journey across the continent are Hema Maps’ Outback NSW, Outback Qld and the Top End & Gulf Country maps.

COMMENTS