To some, it’s a boxy old 3 Series BMW that looks a bit odd with its 15-inch wheels and sky-high ride height. But, for those who remember Group A touring cars, or know high-performance 1980s road cars, then this little square German two-door sedan is seriously desirable.

This feature was originally published in MOTOR’s April 2013 issue

Launched in 1982, the second-generation 3 Series was a hit from the outset. With the wide range of drivetrains, body styles and trim levels, it won more hearts with great dynamics and — in the case of the 323i — a fair bit of grunt, too.

They didn’t muck around. The bonnet and roof are the only body panels an E30 M3 shares with a regular two-door E30 BMW. There were 12 unique body alterations made to the E30’s shell. For example, the boot-lid and rear windscreen profile were changed for aerodynamics, the front bar widened and deepended, while all four guards were boxed and flared to house much fatter race rubber and the wider track.

It wasn’t just cosmetic, as the E30 M3 runs unique five-stud suspension, over the regular E30’s four-stud set-up. The M-car retained the trailing arm set-up in the rear, but scored a beefier front-end. There were E28 5 Series wheel bearings and caliper mounts, and the strut bodies were enlarged for beefier dampers. The swaybar end link was also moved from the control arms to the strut body.

The control arms were also changed to lightweight aluminium units, fitted with an offset solid rubber bush to give more caster angle.

While the body featured plastic bumpers (like the Series II E30), the M3 retained the slimmer taillights of the earlier chrome-bumpered model. Despite the Frankenstein mixing and matching of body parts, the fat box guards, sleeker roofline and squat proportions mean it is one of the best looking homologation specials from the mid-’80s.

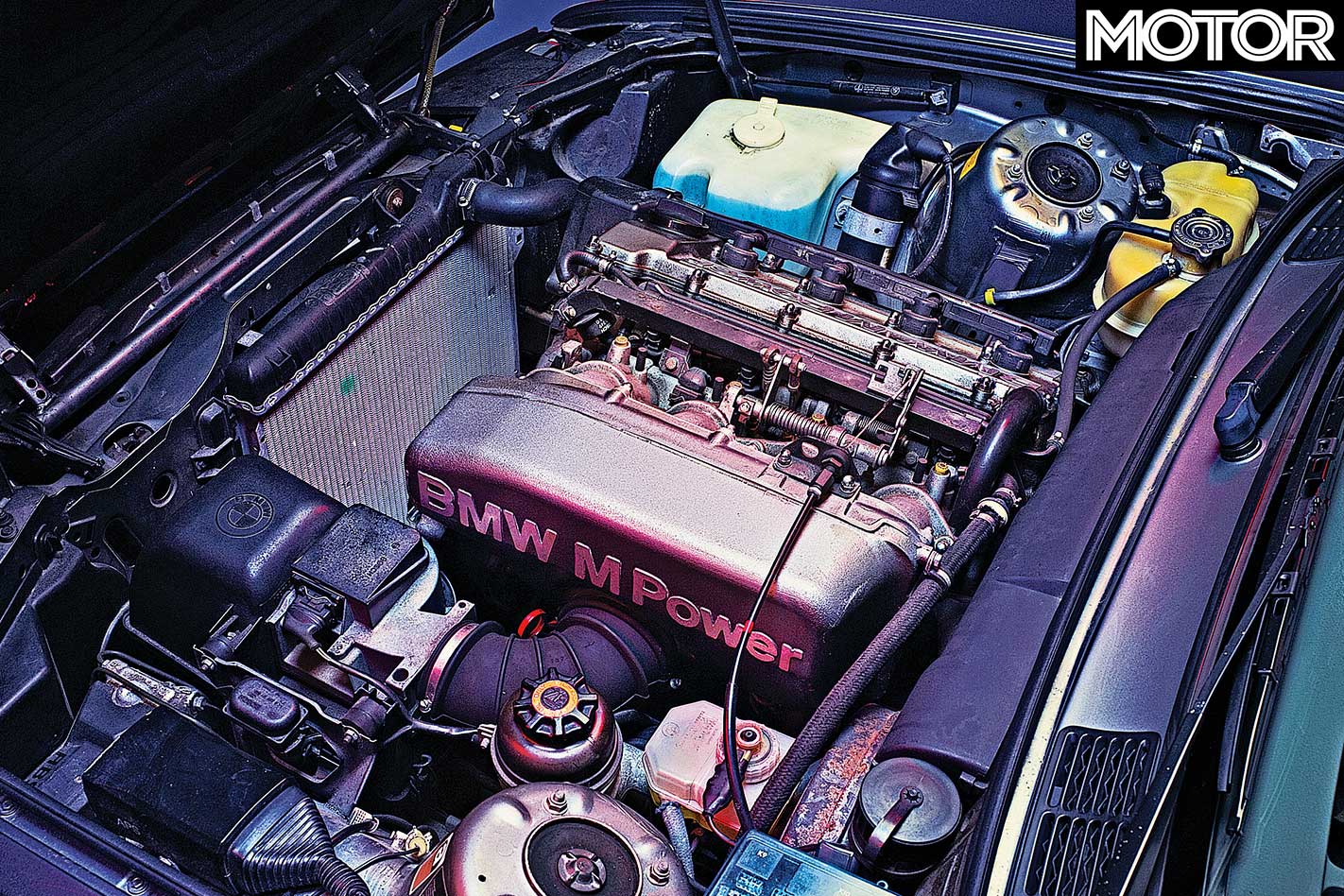

Under the bonnet, M Sport took the radical approach of ditching the M20 straight-six for a four-cylinder to improve steering feel and accuracy. However, it wasn’t the SOHC, low-revving 1.8-litre the 318i had to deal with.

M Sport took a bare M10 four-cylinder block, bored it out and reinforced it in similar fashion to their existing M88 straight-six (found in the M1, M5 and M635CSi). They also shortened the four-valve, DOHC cylinder head from the M88 by two pots and fitted that to the new four-cylinder, before slapping a name on it: S14B23.

The 2.3-litre S14 also scored individual throttle bodies and a timing chain, rather than the timing belt regular E30s dealt with. Early motors made around 143kW (147kW for the non-catalytic converter-equipped models.).

While that doesn’t sound like a whole heap of power, the heaviest variants of the regular M3 (not including the rare convertible) tipped the scales at 1300kg. Nearly 150kW in a lightweight package with taught handling, sharp steering and rear-drive balance made for a car that just begged to be belted.

At the time, a road-going M3 was almost a sleeper… for those countries fortunate enough to drive on the wrong side of the road. Unfortunately for Australia, BMW never saw fit to make a right-hook E30 M3, meaning that the far tamer 325iS was the hottest E30 we could get our hands on.

Overseas, America scored lower-spec M3s fitted wtih catalytic converters and an overdrive transmission, while Europe scored the infamous dog-leg gearbox (with first gear where 2nd normally resides).

With companies like Prodrive and AC Schnitzer running the cars in both rallying and touring car racing, the E30 M3 soon made a name for itself against the Mercedes-Cosworth 190E 2.3-16v, Ford Sierras and Alfa Romeos, seeing action in Aussie, German, British, Belgian, French, and Italian touring car racing in the hands of some of the best tin-top drivers of the day.

Championship wins included our ATCC (by Jim Richards in the JPS car), as well as Germany’s DTM, the British Touring Car Championship, European Touring Car Championship and the one-off World Touring Car Championship in 1987, plus multiple consecutive Nürburgring and Spa 24 hour races.

But, as the Group A class attracted new manufacturers and more powerful turbocharged machinery, BMW had to stay on their toes. To keep up, Evolution models were released. Initially they fattened the intake cam profile, increased the exhaust cam duration, bumped up the compression ratio and worked out a more efficient cylinder head intake port layout.

With freer-flowing headers, the little atmo four-pot made an impressive 160kW. The Evo 1 and II grew wheel size from 15×6-inches up to 16×7.5, scored lighter rear and side glass, a lighter bootlid, and a deeper front spoiler.

On the tail of the M3’s race track success, BMW released several special editions — Europa, Ravaglia (named for touring car driver Roberto Ravaglia), Cecotto (after touring car driver Johnny Cecotto) and Europameister — based off Evo I and Evo II models. They featured different trim and body colour combinations, but were mechanically standard Evos.

The last upgrade, and arguably the best, was the Sport Evo (aka Evolution III). To match the race car’s new 2.5-litre motor, the road car also copped a bump in capacity. Super-rare with less than 600 made, the Sport Evo also scored higher lift cams, fatter front bumper, adjustable splitter and rear wing, brake cooling ducts and much more. It was able to stomp out a not-inconsequential 177kW — or 50kW more than a 5.0-litre VL Commodore of the same era.

While that may be impressive, power for the last Group A E30 M3s was thought to be around 200kW, though by the end of the E30’s run in 1992 that was less than half of what the turbocharged GT-Rs and Sierras were producing.

There were also 786 convertibles produced (including one Sport Evo convertible), but they were heavier and slower than the coupes, and never won anything except a free perm from your local Vidal Sassoon.

While we missed out on the original run, the rise in private imports in the early-2000s opened the door for many Aussie fans to get their hands on an E30 M3. Though the right-hook conversion wasn’t as straight-forward as you’d initially think (being that plenty of right-hand drive E30s were sold in Oz), the reward is that it’s rare to see a butchered conversion these days.

As cars have been raced, crashed or thrashed over the years, rarity is starting to cause values for some models and specs to rise. And who doesn’t want to pretend they’re Jimmy Richards in that JPS race car, blasting over Skyline at 9000rpm?

The Good

1 – The 2.3 is good, but the 2.5 Sport Evo’s motor is epic – a screaming, wailing example of engineering excellence 2 – The M3’s guards and roof give it an awesome stance, especially in slammed race-spec on fat wheels 3 – It is the four-wheeled definition of ‘visceral’. Engaging and entertaining, it is pure driving joy

The Bad

1 – It isn’t until you get into an E30 M3 that you realise just how old they are, and how old they feel 2 – You can’t get away from the fact that E30 M3s just aren’t what you’d consider a fast car these day 3 – Buy a shabby E30 M3 and you’ll hate life. Rust, wiring problems, engine rebuilds that’d bankrupt a Packer…not fun.

Chop n’ Shop

Many would consider modifying an E30 M3 to be tantamount to sacrilege. However, as a homologation car, they were actually designed to be fettled for improved performance (just like WRXs, R32 GT-Rs, Evos and the like).

Aftermarket suspension, big brake kits, engine components and wheels and tyres are all easily sourced to turn a stock M3 from a fun weekender into a serious track (or street) weapon. On top of this, there is a huge number of aesthetic upgrades for the little BMW, from carbonfibre body panels to seat upgrades, different steering wheels, carbon door trims and much, much more.

The hardcore Europeans and Americans even go so far as to swap different drivetrains into the M3, in the hunt for straight-line speed. Turbocharged and supercharged E36-generation straight-six motors (known as S50B30 and S50B32) are an easy addition, while the E46’s S54B32 3.2-litre in-line six is much harder to fit, but is possibly the best BMW six to pick.

The crazy tuners don’t stop there, though. There are quite a few Chevrolet LS1-powered E30 M3s (due to the engine’s compact size and light weight), along with 300kW 5.0-litre V8 versions from the E39 M5 (known as the S62B50) and even 5.0-litre, 375kW, 8250rpm V10 (S85B50) engine swaps.