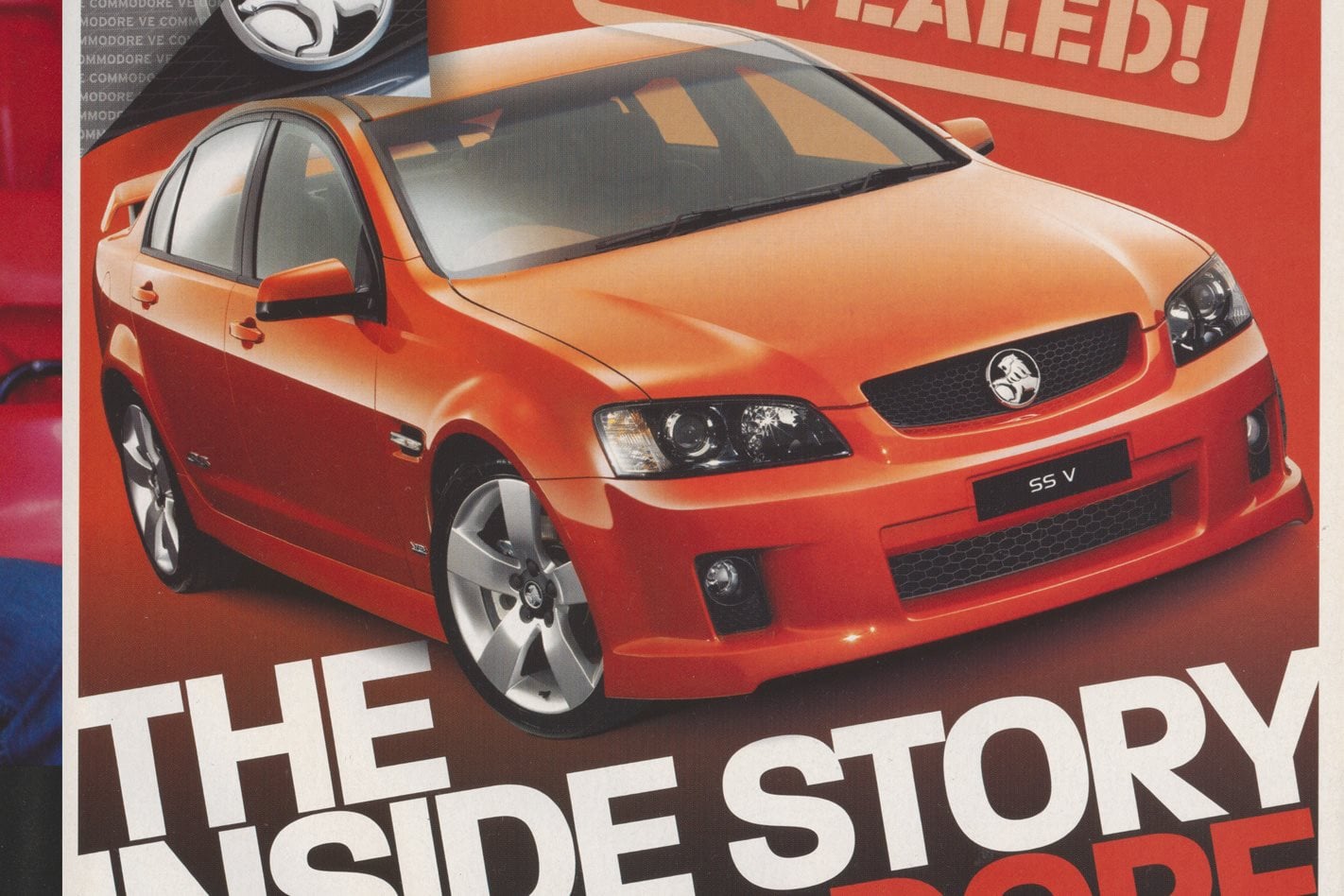

FOR HOLDEN, the new VE Commodore is an opportunity seized, a challenge accepted.

“We all wanted to do a BMW; there’s no shame in that,” says plain-talking engineering and design executive director Tony Hyde. “We all wanted to do the stuff that the good German guys had done, but we knew we had to sell it for $35,000, to make life a little difficult.”

It’s a succinct summary of the magnitude of the task Holden set itself with the VE Commodore.

Money is one of the ways in which the scale of the 2006 Commodore program is different from anything in Holden’s history. The bill for the VE program totals more than $1 billion, much more than Holden has spent on any previous Commodore.

It’s been more than 30 years since anything like the VE happened at Holden. The HQ, which spawned a generation of Holdens that preceded the 1978 switch to the first European-designed and engineered Commodore family, was the last time something this big had been attempted.

The decision that Holden would design and engineer its own brand-new Commodore wasn’t automatic. If things had turned out just a little differently, Australia would have had a Cadillac-based Commodore instead of a BMW-like Commodore.

Planning executive director Ian McCleave recalls the early stages of the VE story clearly. It began soon after Holden’s ’97 launch of the VT, the basis of every Commodore model from then until now. Rob McEniry, then a General Motors executive, but these days the man running Mitsubishi Australia, had been given an important task.

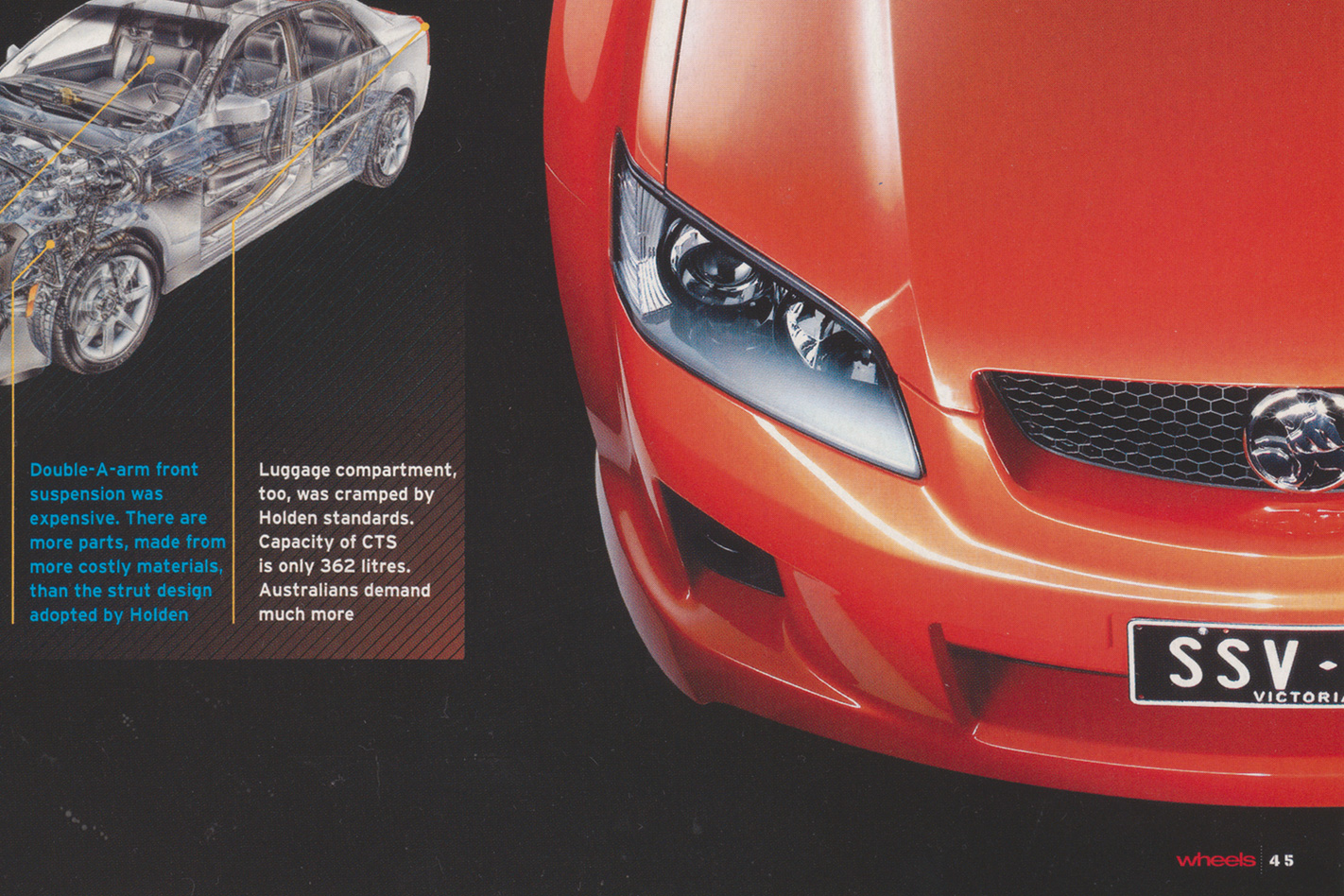

“McEniry then put a team in the USA. They looked at all the opportunities for taking a vehicle like the next-gen Commodore off the Sigma platform, which was under development for [Cadillac’s] CTS and, later on, the STS.”

Some of McEniry’s Australians were noticed by one of the American senior engineers working on the Sigma.

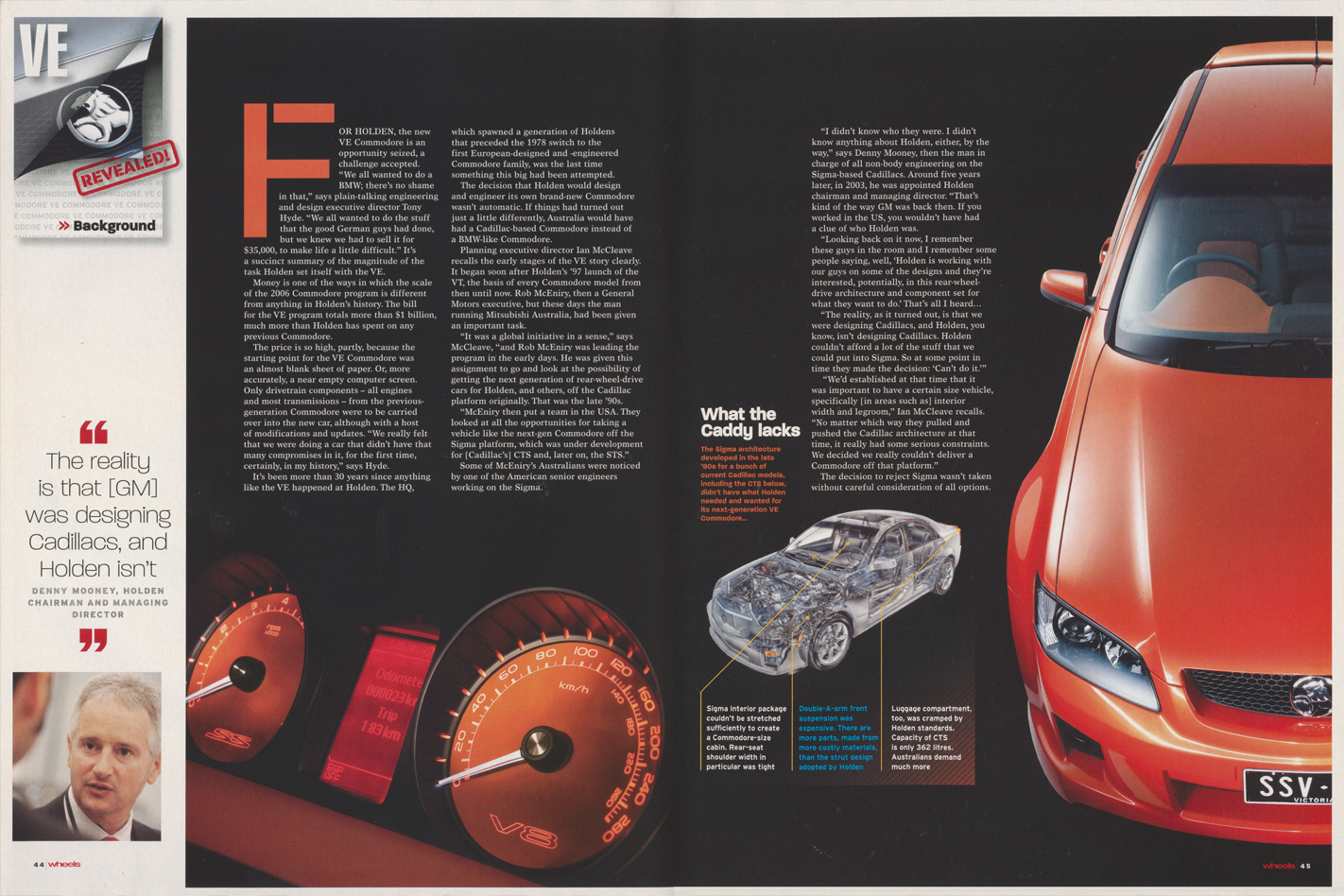

“I didn’t know who they were. I didn’t know anything about Holden, either, by the way,” says Denny Mooney, then the man in charge of all non-body engineering on the Sigma-based Cadillacs. Around five years later, in 2003, he was appointed Holden chairman and managing director. “That’s kind of the way GM was back then. If you worked in the US, you wouldn’t have had a clue of who Holden was.

“The reality, as it turned out, is that we were designing Cadillacs, and Holden, you know, isn’t designing Cadillacs. Holden couldn’t afford a lot of the stuff that we could put into Sigma. So at some point in time they made the decision: ‘Can’t do it’.”

“We’d established at that time that it was important to have a certain size vehicle, specifically [in areas such as] interior width and legroom,” Ian McCleave recalls.

“No matter which way they pulled and pushed the Cadillac architecture at that time, it really had some serious constraints. We decided we really couldn’t deliver a Commodore off that platform.”

“We went into all sorts of loops on reskinning VT, or reskinning VT but maybe with new some suspension, [or] all-new, doing something off Sigma,” Tony Hyde remembers. “We got into this whole planning thing, where they had four, five, six, seven bloody alternatives, ranging from the most expensive to virtually do nothing … and commit suicide.”

The reason Holden was so interested in adopting Cadillac’s architecture was simple. Opel, Holden knew, had decided to kill its Omega sedan. It was the end of the line for the series of large, rear-wheel-drive European cars that had served as a basis for every generation of Australian-made Commodore since the late ’70s.

The only potential alternative donor was the American Sigma.

In 2000, the decision was finally made that Holden should begin design and engineering work with a clean sheet. Almost clean, anyway. “Powertrains are locked in earlier than the vehicle itself, in a sense,” says Ian McCleave. “You’ve got a powertrain plan that is basically dictated at corporate levels.

“We deliberately wanted to get that into the VZ earlier, so we’d have the experience with it,” he adds, alluding to the 2004 introduction of the all-new Alloytec V6 engine. “From my perspective, it was very important to get it into the current platform, learn all about it, so we weren’t launching a new car and a new engine together.”

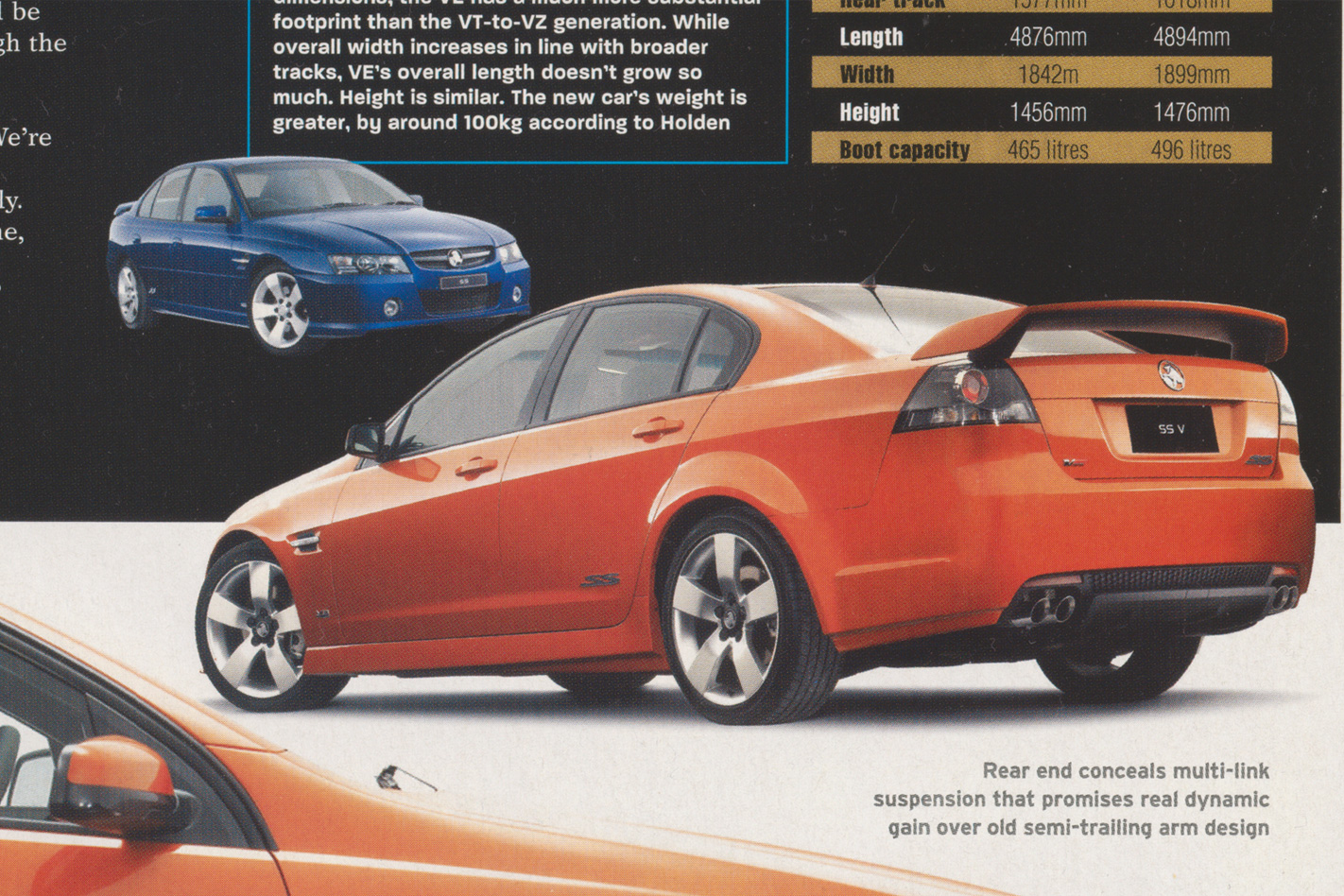

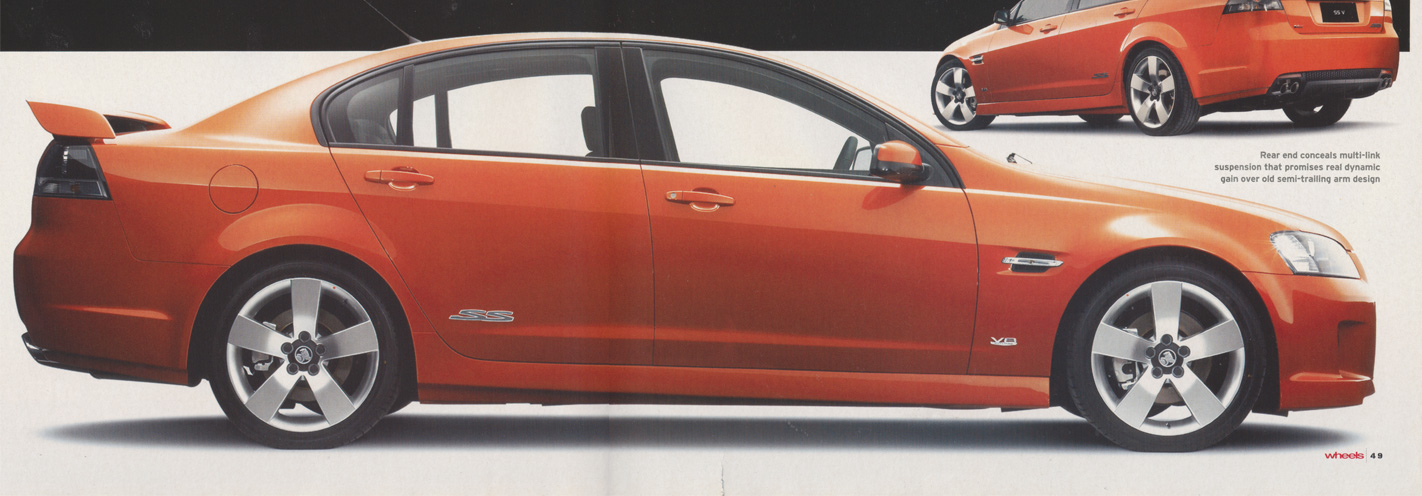

Other technical decisions were also debated, suspensions especially. “The front suspension was awfully tired,” admits Tony Hyde. “And the rear suspension, alright, it’s a nice semi-trailing arm thing, but that wasn’t what we wanted to do.”

Hyde headed the faction favouring simpler, cheaper struts with their single A-arms. “We clung to, ‘Well, shit, BMW has got struts. It can’t be that bad, you guys.'”

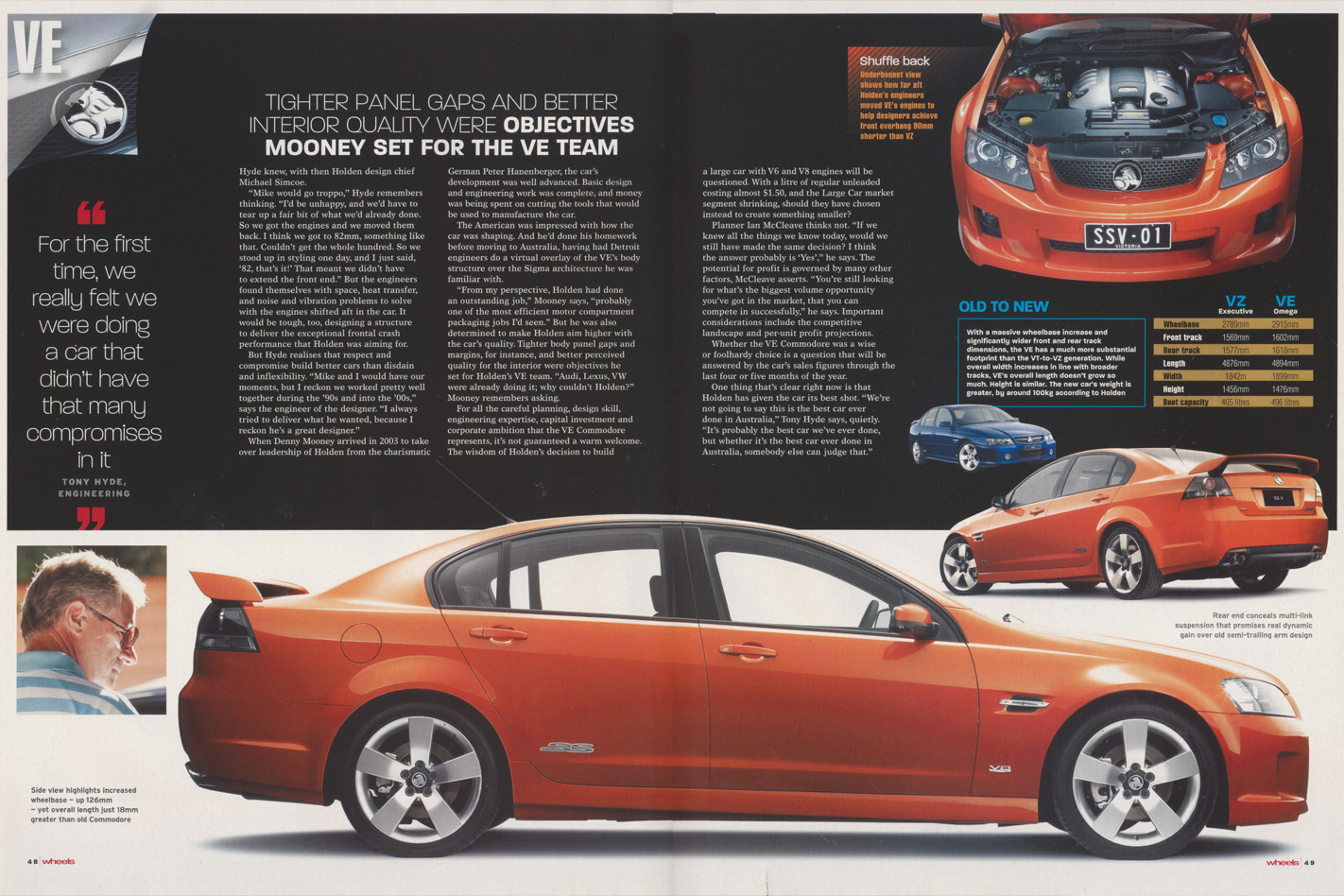

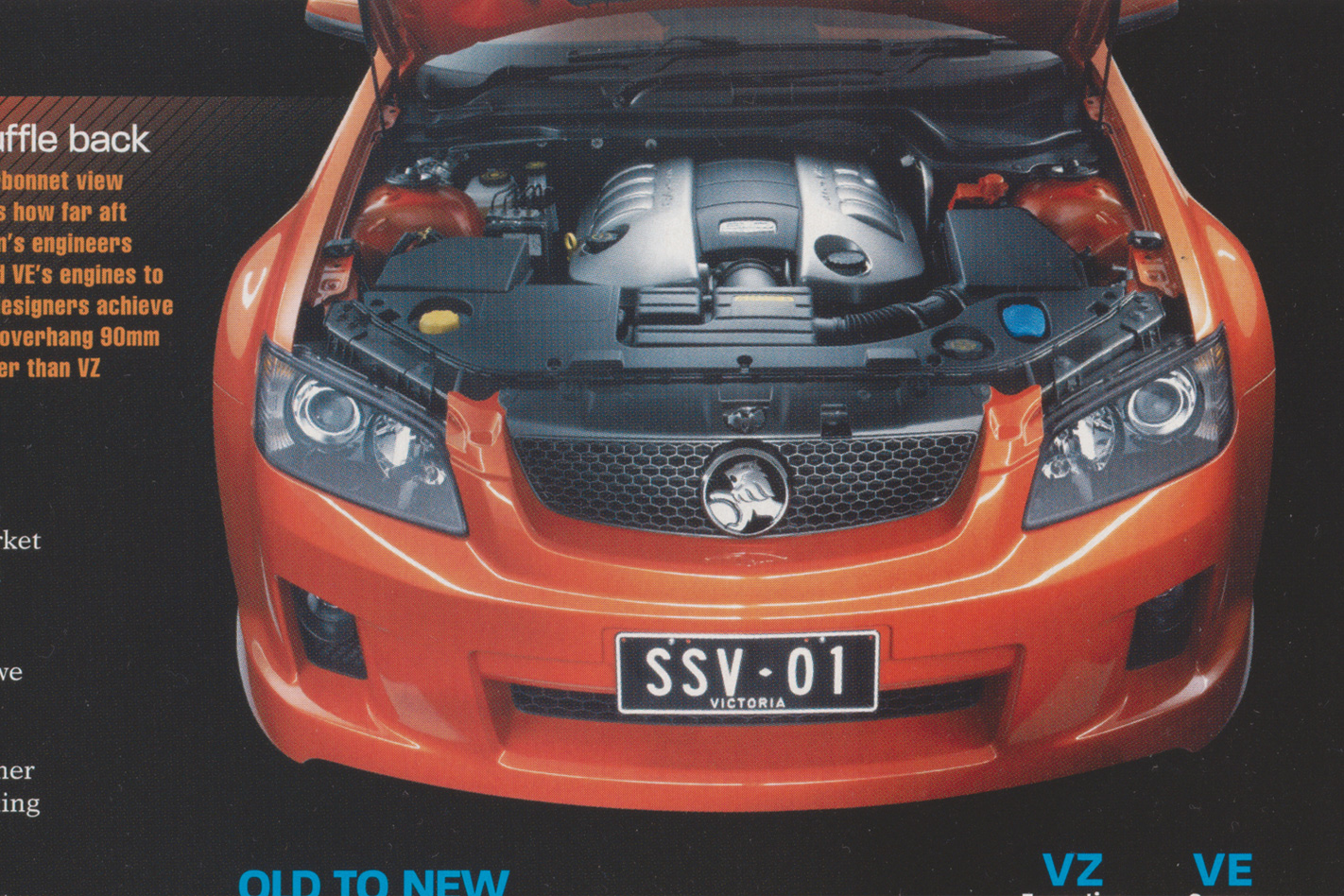

The toughest battles as the VE took shape were over the car’s all-new body structure. While the design department wanted to minimise frontal overhang, this would create problems for the engineers. With the car’s structure still taking shape, Hyde’s crash specialists were insisting on 100mm of crush space ahead of the VE’s engines. As the design then stood, there was only 60mm.

The only obvious solution was to extend the frontal overhang by 40mm. This spelled trouble, Hyde knew, with then Holden design chief Michael Simcoe.

But Hyde realises that respect and compromise build better cars than disdain and inflexibility. “Mike and I would have our moments, but I reckon we worked pretty well together during the ’90s and into the ’00s,” says the engineer of the designer. “I always tried to deliver what he wanted, because I reckon he’s a great designer.”

When Denny Mooney arrived in 2003 to take over leadership of Holden from the charismatic German Peter Hanenberger, the car’s development was well advanced. Basic design and engineering work was complete, and money was being spent on cutting the tools that would be used to manufacture the car.

The American was impressed with how the car was shaping. And he’d done his homework before moving to Australia, having had Detroit engineers do a virtual overlay of the VE’s body structure over the Sigma architecture he was familiar with.

For all the careful planning, design skill, engineering expertise, capital investment and corporate ambition that the VE Commodore represents, it’s not guaranteed a warm welcome. The wisdom of Holden’s decision to build a large car with V6 and VS engines will be questioned. With a litre of regular unleaded costing almost $1.50, and the Large Car market segment shrinking, should they have chosen instead to create something smaller?

Planner Ian McCleave thinks not. “If we knew all the things we know today, would we still have made the same decision? I think the answer probably is ‘Yes’,” he says. The potential for profit is governed by many other factors, McCleave asserts. “You’re still looking for what’s the biggest volume opportunity you’ve got in the market, that you can compete in successfully,” he says. Important considerations include the competitive landscape and per-unit profit projections.

Whether the VE Commodore was a wise or foolhardy choice is a question that will be answered by the car’s sales figures through the last four or five months of the year.

One thing that’s clear right now is that Holden has given the car its best shot. “We’re not going to say this is the best car ever done in Australia,” Tony Hyde says, quietly. “It’s probably the best car we’ve ever done, but whether it’s the best car ever done in Australia, somebody else can judge that.”