Another day on the job then; Head Office wants me to ponder the future of automobilia with a fellow industrial designer and to begin the exercise by transporting 545kW-worth of Ferrari F12 Berlinetta from one side of Sydney to the other for reference.

Luckily, this shouldn’t be too taxing, preliminary research indicates that the thing is quite breathless beyond 340km/h. Nonetheless, the notion of routing the journey via Goulburn springs to mind until cruelly doused by management’s clearly phrased suggestion that some industrial designers are a little, no, a lot, more important than others. We wouldn’t want to keep one-such waiting would we? Especially when that designer goes by the name Flavio Manzoni.

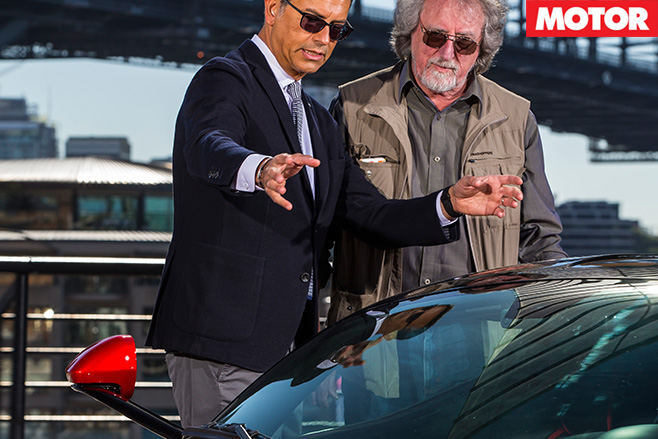

In 1993, at age 28, Manzoni joined the Centro Stile Lancia and subsequently worked for various other manufacturers, including Maserati, before moving on to redefine the Bentley and Bugatti marques and win nearly every award possible. In 2010, he was appointed Ferrari’s first-ever senior vice-president of design.

My instruction is to meet the man, here on his first visit to Australia, and discover the future of the car. But I don’t need to, I already know: scarily silent, battery-sucking self-drivers hell-bent on saving humanity despite itself. But the editorial premise is that a Ferrari is much more than a car – it represents the ultimate expression of man and machine entwined in purpose and pleasure. With Manzoni at the helm, Ferrari can be expected to set the standards of automobile design for decades to come.

The experience of Manzoni’s handiwork – even if limited by a schedule to city roads and photography – provides something tasty to chew on while awaiting the man himself. At first sight it threatens to be quite a mouthful; the second, longer look reveals something deeply satisfying.

But the interior is the big surprise. Where I’d anticipated needing an hour of instruction to learn how to even start the thing, I find that, instead, virtually everything falls to hand where you’d expect it and operation is almost completely intuitive. Granted, the workstation isn’t conventional, but it works.

Devoid of the infuriating engine-start/handbrake/gear-selection/switching gimmickry that currently corrupts so many cars, it perfectly illustrates the difference between novelty and genuine improvement.

With that social contribution comes the Big Question. Given that everything’s going electric, in future, what will a silent Ferrari be like? It’s a question that strikes right to the heart of discussion with Manzoni: Where does the future of automotive excellence lie? What senses will it indulge?

At only 51, the weight of the man’s accolades – among them induction into the Hall of Fame at the National Automobile Museum of Italy – and the sheer impact of his work give him serious design authority and his willingness to share it in a second language is rare and rewarding.

He understates – the marque’s first hybrid boasts a total 708kW. A constraint is the physical accommodation of both V12 and electric power systems and the daunting array of hardware that consummates their union.

“In the past, it was easier to see the role of a designer like an artist, working with certain constraints, but not many,” he says. “But here the project is so technologically complex that it’s not possible anymore, first to define the technical configuration, then give it to somebody else to make a kind of suit/cover on top. So the problem is how to reconcile the two different aspects – the engineering complexity and the pure beauty.”

The sheer volume of problems were numbing, but Manzoni and his team addressed them all, from downforce and drag to ingress, access, vision and venting, as a singular enterprise. The result is a blend of function and beauty beyond anything that even this fabled marque has achieved before. “For sure, the complexity of the project makes our job more difficult, but problems are opportunities.” He smiles. “That is design to me.”

Yet it is indicative of the man that he sees no car as his defining legacy. His greatest pride is his team. Ferraris used to be penned externally, largely by Pininfarina. But that era is over now. Created in 2010 with a staff of just four, Centro Stile Ferrari now numbers 70 people and is responsible for all Ferrari road cars, from production stalwarts to exotic one-offs, and represents the marque’s new era.

As for developing a Tesla-chaser, he simply quotes Marchionne on an electric Prancing Horse: “You’ll have to shoot me down.”

Whilst the designer is understandably reluctant to divulge details of future Ferraris, he has no hesitation in revealing his own philosophy. He firmly believes that Ferrari’s evolution must revolve exclusively around sports cars. Whilst this may allow the seating of four, he is adamant that two doors are the limit – not that that’s too limiting.

Although Manzoni resists discussing it, there’s talk of a revolutionary body concept with full-length gullwing doors and no B-pillars that could be the first four-seater from Maranello that treats all occupants with equal courtesy.

“At home I have two pianos. One is a fantastic Yamaha, completely digital, and then I have a Steinway grand piano. Which one do you think I play? The Steinway, because the … motion … the feel given by the harmonics, I don’t know in English how to say…” He doesn’t need to.

His work already says it for him. Industrial designers, at their very best, seamlessly blend the realities of engineering with the rewards of romance – and none do that better than Flavio Manzoni.

Okay, the man may have cost me a rich thrashing of his Berlinetta but, damn it, by any other measure he’s surely a credit to the species.

One thing Ferrari’s nailed

No marque epitomises Grand Prix racing more than Ferrari, a heritage clearly seen in the nose/spoiler of LaFerrari. But the union’s true value is the transfer of F1 advance to road cars and the F12berlinetta’s helm is a splendid example. The vital but normally scattered and stalked controls of starting, indication, lighting and wiping are grouped on it within instant reach, yet differ in feel so as to allow tactile identification of each without sighting.

Innovative, intuitive and effective, the wheel illustrates the benefit of sating more senses (including common) than just sight. And the difference between styling and design.