Time can move slowly at Maranello. Every decision within Ferrari’s hallowed headquarters requires a Janus-like focus on the future with a deferential nod to the past. Models morph gently across generations and it’s often only with the benefit of hindsight that genuinely pivotal models can be identified. The Ferrari F355 is one such car.

At the time of its introduction in 1994, it promised to be little more than a fairly extensive refresh of the much-maligned 348. It was, in fact, a changing of the guard. Before the F355, V8 Ferraris had a certain place in the hierarchy. They provided a taster of the excitement and charisma of the senior 12-cylinder supercars at a more affordable price point. The F355 fundamentally changed the focus of Ferrari’s road-car division. The mid-engined V8 became the point of the spear, the dynamic exemplar around which the rest of the product line pivoted.

Of course, you could point to a whole host of other reasons why the F355 marked a change in the way Maranello did things. It was the final hand-built production Ferrari, yet it was the first to lean on computer-aided design. It was the first V8 in the post-Enzo Ferrari era and was the last V8 to feature pop-up headlights. It was the first Ferrari to be fitted with a robotised ‘F1’ transmission and the last to rely on a steel monocoque chassis. But it was what the F355 meant that resonates today.

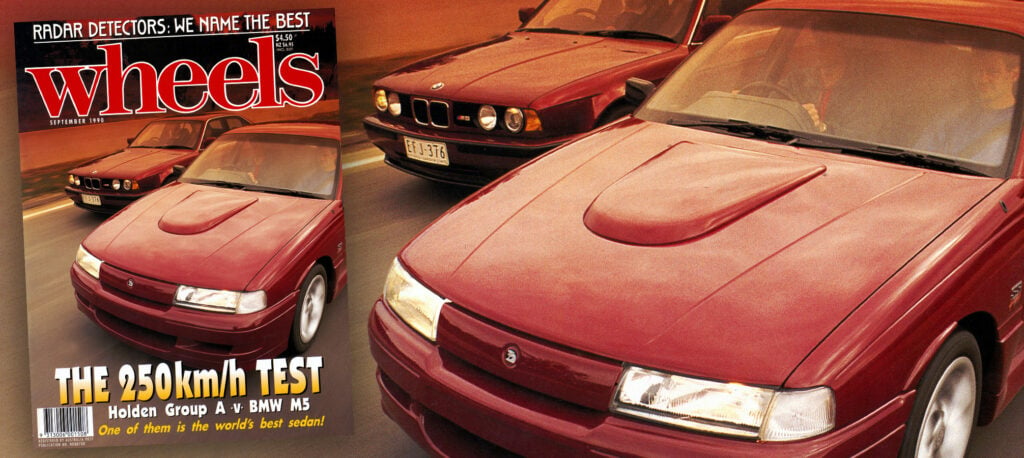

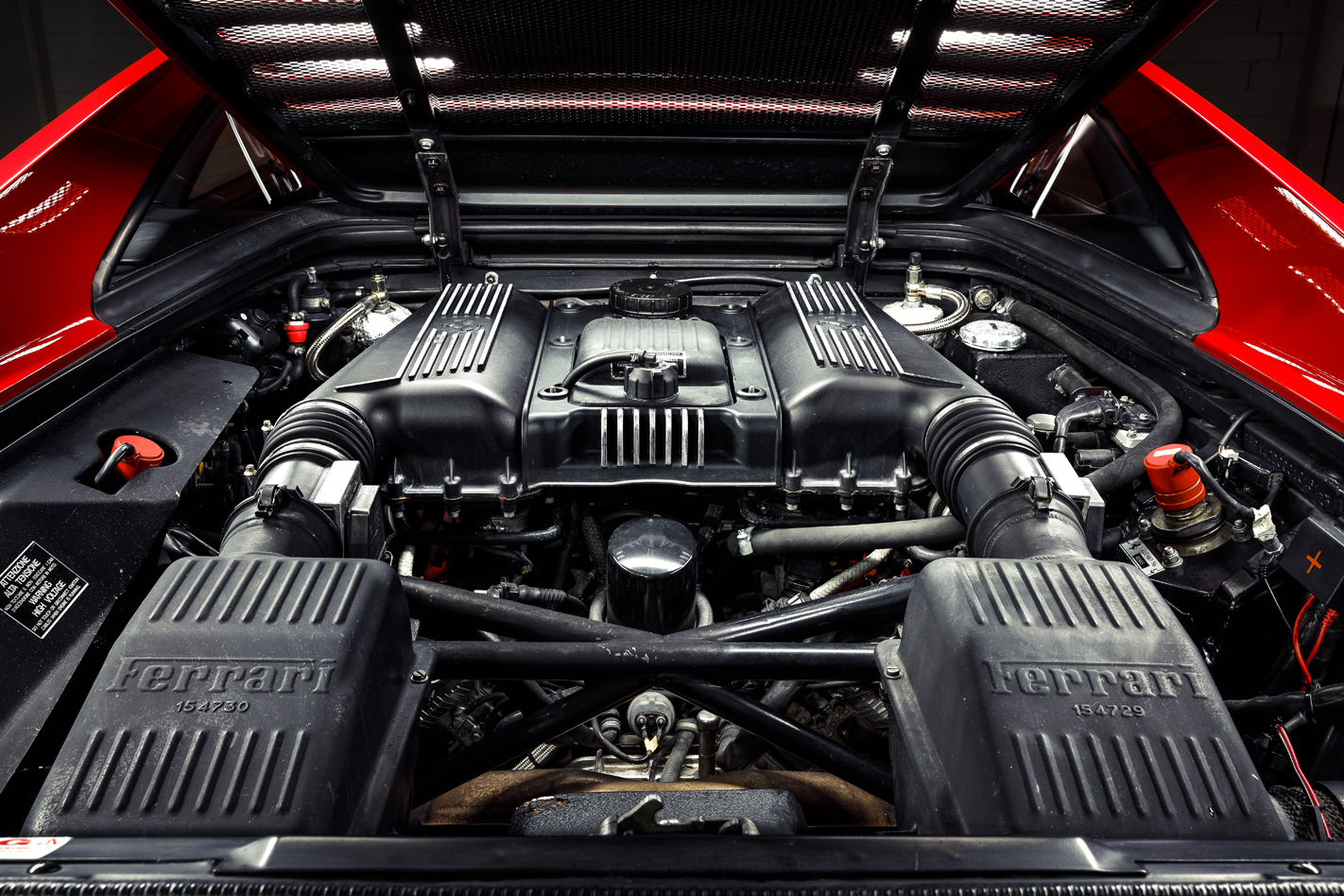

Peter Robinson was quick to clue into this. “The cheapest Ferrari is also the quickest Ferrari,” he noted in Wheels’ first drive (August 1994), going on to ponder the relevance of the 12-cylinder flagship, the 512TR. Around the Fiorano circuit, the F355 was fully seven seconds quicker than the 348 and three seconds quicker than the 512TR. Of course, having the most efficient normally aspirated engine in the world helped its cause. The five-valve head, titanium rods, forged pistons and twin exhaust systems lifted power from the 3496cc V8 to an unprecedented – for a naturally aspirated engine – 80kW per litre, eclipsing even the 76.8kW/L of the McLaren F1.

Although the form factor of the 348 remained, virtually everything else changed. The roof, glass and front guards were carried over but every other external element was new. And with good reason. Testarossa side strakes were certainly striking when they were originally penned in the early ’80s, but the 348’s beslatted flanks looked passé more than a decade later. The replacement program for the 348 began in 1990, just as the Honda NSX arrived on the market. One year later, Luca di Montezemolo arrived at Ferrari and, upon seeking advice from test drivers who had benchmarked the Honda, tore up the plans for the company’s response, ostensibly a more powerful 348. He also inherited the 456GT program in its late phase of development, but the F355 represented a way for di Montezemolo to underscore his bona fides and create a lasting impression.

“I started in December ’91,” recalls di Montezemolo. “After Italia ’90 [the soccer World Cup project he oversaw] went so well, I had given myself a present and bought a 348. It was terrible. So I’m at the first meeting as CEO and I asked to be presented with our range. ‘Okay, we have the Testarossa, we have the 348 – very good car, innovative, eight cylinders,’ and I said, ‘Please stop. This is a shit car. So don’t say this to me; I am a client, I know what this car is like.’”

Berlinetta coupes and the car featured here, the F355 GTS targa, were launched first, at a strangely muted press event coming shortly after Ayrton Senna lost his life at Imola. Senna had lunched with di Montezemolo at his home prior to the race and pledged to explore a release from his Williams contract in order to join the scuderia.

The 348 Spider continued into 1995, making way mid-year for the soft-top F355 Spider. An F355 Challenge model appeared in late 1995, for the Ferrari Challenge race series. The mechanicals were left unchanged but brakes, suspension and tyres were upgraded to track spec, along with exhaust and cooling enhancements. Between 1995 and 1998 the Challenge gradually grew more track-focused, with 108 cars eventually produced, of which 28 were right-hand drive. All featured the manual six-speed transmission, despite the debut in 1997 of the F1 paddleshift sequential ’box.

In the context of its contemporaries, the F355 was a rocketship. Ferrari claimed an ability to hit 100km/h in 4.7 seconds, which put it on par with ‘proper’ V12 supercars like the Lamborghini Diablo and bettered circuit emigres like Porsche’s fearsome 993 Carrera RS 3.8. Maranello’s famously optimistic claims weren’t too far off the mark either. Former Le Mans winner Paul Frère tested an F355 Berlinetta at 4.9 seconds to 60mph and 13.3 for the quarter-mile. Frère claimed Paolo Martinelli’s F129B V8 was “probably the best sports-car engine ever made.”

It’s worth noting that not all of these engines are created equal. Or rather their electronics aren’t. When the F355 launched it featured Bosch Motronic 2.7 engine control system, with dual mass-air-flow sensors, two fuel pumps and a duet of lambda sensors. These early 2.7 models feel a good deal livelier and more aggressive in their throttle response than the later Motronic 5.2 models, introduced in 1996, which are cleaner and have a noticeably smoother idle. At the same time, the delicate three-spoke steering wheel was changed for a chubby airbag-equipped item. It seems F355 aficionados aren’t hugely safety-focused because most would prefer the early 2.7 cars with simpler OBD1 electronics.

That’s not to say that the F355 is a straightforward ownership proposition. As beautiful as they are, it’s unlikely many owners would recommend a used example to a close friend. What goes wrong? There are myriad ways to land yourself a big bill. That’s why many potential used buyers, as seduced as they were by the F355’s styling and soundtrack, migrated to either the older 328 or the newer 360 Modena.

There are five key problems to look out for. The first is rust, most specifically corrosion at the bottom of the coupe and targa’s roof buttresses where they meet the rear wing. This is caused by a chemical reaction where aluminium and steel meet, which then results in cracking. The solution is a one-off lead treatment, or just buy a Spider and give the issue a swerve.

The interior plastics are another recurrent issue. In short, the rubberised thermoplastic covering on much of the switchgear degrades over time, becoming sticky and rubbing away. It’s an issue of age and not UV exposure as NOS items that are still in the box suffer the same fate. There are companies that can strip and plastidip the offending parts but it’s a tedious process. Likewise the leather atop the dash and airbag cover can shrink and crack, especially in hot climates. Many replace the leather with Alcantara which is hardier and reduces windscreen reflections.

The big-budget item that is virtually a lottery is when the F355’s exhaust manifolds will give up the ghost and crack. Factory replacements are the thick end of $20K, but aftermarket manufacturers offer better alternatives for half that. The issue usually arises at between 35,000 and 55,000 kilometres, and if one side goes, the other will fail shortly thereafter. In short, they’re too thin, using 2mm-gauge metal rather than the 4mm-thick walls of specialists like Tubi or Capristo.

Worn valve guides are another recurrent F355 issue. The factory initially used bronze valve guides and Ferrari reckons that about 20 percent of 1995MY cars would experience excessive valve guide wear and poor engine compression as a result. This has given early valve trains an exaggerated reputation for fragility. Most affected cars will be fixed now. However, even with the newer valve guides introduced post-95, problems arose. A bad batch of valve guides also found its way into 97/98MY cars. Valve pitting is also an issue on F355s that aren’t used regularly.

The final caveat is just the general high cost of service. The Propulsore Completo – Ferrari’s name for the engine and transaxle – fit snugly onto a subframe that needs to be removed from the car for routine belt servicing every 36 months. Wise owners will also schedule a major service to coincide, which will cost upwards of $10,000.

Fortunately there’s a significant amount of F355 expertise out there. This was the first Ferrari to achieve 10,000 sales but it pays to recognise that despite it now costing BMW M3 money to buy, it still requires an Italian-exotic maintenance budget. The way it drives still stands up. In fact, it’s a better fit for today’s driving than many modern supercars which feel overtyred and underinvolving at sensible speeds. The F355 represents a high-water mark: perfectly proportioned, wonderfully charismatic, achingly beautiful and, by modern supercar standards, tiny. There’s a fairly high bar to be recognised as a great Ferrari. The F355 clears it with ease.

The Ferrari F355 by the numbers:

Fast Fact

One of the rarest F355 models is the runout Serie Fiorano, launched in March ’99. Just 104 were produced, all in the Spider body style. In total 100 went to the US, three were sold in Europe and one went to South Africa. Brakes, steering and suspension were upgraded to near-Challenge spec.

Who owns one?

John H- Victoria

“I owned an F355 Spider for over 10 years. It was fairly well exercised and most of the major issues were addressed. I remember the exact moment that I realised I was in for a colourful ownership experience. It came on the morning after I bought the car when the battery was as flat as a pancake. You need to remove the front wheel to get to the battery. The manual is no help. It was outsourced to Pininfarina and it’s a work of glorious fiction, telling you that the battery’s in the luggage bay. Pininfarina should probably stick to drawing cars. I did the maths and realised that 30,000km of Uber rides were cheaper than driving the F355. Still worth it.”

Specs

Model: Ferrari F355 GTS

Engine: 3496cc V8 (900), dohc, 40v

Max power: 280kW @ 8250rpm

Max torque: 363Nm @ 6000rpm

Transmission: 6-speed manual

Weight: 1440kg

0-100km/h: 4.7sec (claimed)

Price: $275,000 (1995), from $180,000 now