We’ve all had those moments where you’re not sure whether you’re awake or asleep. You’d swear it was real, but what your eyes are looking at seems impossible.

This is one of those moments. I’m rolling down Winton’s main straight in a Ford Focus ST-Line with photographer Ellen Dewar poking her camera out the window.

This in itself isn’t unusual, but the focus of Ellen’s lens is a growling, popping Toyota Celica GT-Four wearing a white, black and yellow livery like someone’s hit the race modification button in Gran Turismo.

This Celica, registration YYO 221, is a legend of Australian rallying, one of its most successful ever cars. Having secured second place at its debut event, the 1994 Rally of Canberra, YYO 221 went on to dominate 1995, winning nine rallies including eight rounds of the Australian Rally Championship and Targa Tasmania as well as ninth outright at the 1995 Rally Australia WRC round. Behind the wheel, both currently and for those events, sits four-time Australian Rally Champion Neal Bates.

YYO 221 is his favourite car, and to celebrate its 25th anniversary I’m going to drive it. Gulp.

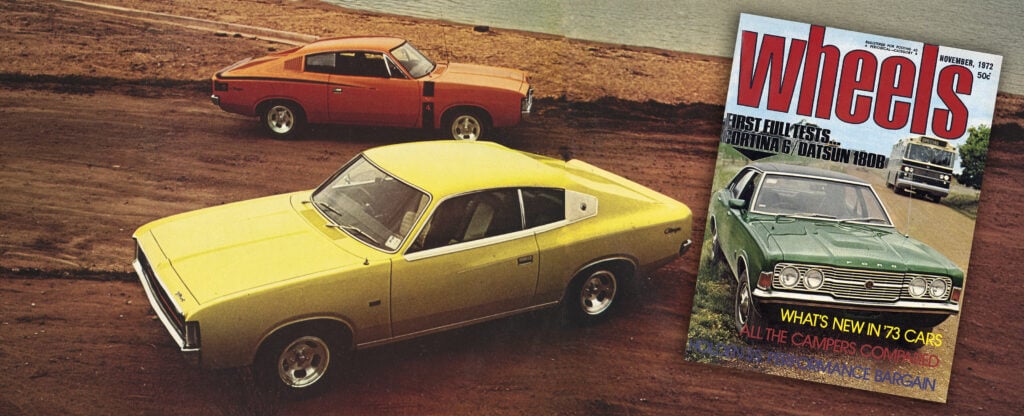

Above: Note Beau Yates’ Toyota 86 drift car to the right, which was present on the day as we compared it to an 86 racing car and Harry Bates’ Yaris rally car

Having secured two straight ARC titles in an ST185 Celica GT-Four it was time for Bates and long-time co-driver Coral Taylor to upgrade to the new ST205. A mild upgrade on paper, the new generation represented a significant step forward for Neal Bates Motorsport (NBM).

“It was the first proper rally car we had,” explains Bates. “If you look at the [ST]185 it was more a road car converted to a rally car.”

NBM took a bare ST205 road car shell and the Toyota Team Europe (TTE) parts catalogue and combined the two, creating the most serious rally car Australia had ever seen.

“It was so different to anything of the time, which were just modified road cars,” remembers Bates.

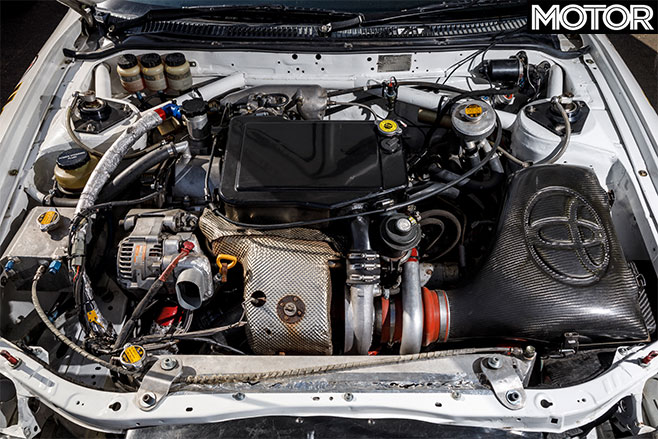

“It was the first full-on proper rally car; it’s got fabricated crossmembers, aluminium uprights, all the TTE bits – steering rack, dampers, block, rods, different crankshaft, pistons, turbocharger, exhaust manifold, intercooler. They were homologated parts so they were all legal.”

Homologated they may have been, but they were still trick parts that cost a bomb.

2003 Toyota Corolla vs Mitsubishi EVO VII rally comparison

“If you look at Group A,” says Bates, “everything is standard looking, so that’s a standard-looking turbo, but they cost $20,000. If you make more than 1.5bar boost with these they’ll split the bores, so they were a special block.”

Breathing through a 34mm restrictor the result was around 220kW/600Nm; “They were called tractors,” says Bates, “because if you came up to a hairpin and grabbed fourth instead of second, it would still go around because it had so much torque.”

Nevertheless, the engine was the ST205’s weakness on the world stage. Keen students of rally history may remember some creative engineering on behalf of TTE, a moveable restrictor that earned the team a 12-month ban for what then-FIA president Max Mosley called “the most ingenious thing I have seen in 30 years in motorsport.”

Bates explains why TTE was pushed to such drastic measures: “When they homologated the 205, restrictors were 36mm, then [in 1995] they went to 34mm and it killed them. The turbo was a little bit big for the engine, but that was the homologated turbo so it couldn’t breathe.”

Away from the pressure of world championship competition, NBM had no need for such dubious devices, not that TTE would’ve made it available to privateers regardless! It’s even less of an issue today, as the Celica runs no restrictor and produces a healthy 270kW at the wheels.

Bates hasn’t always had the car. Racing drivers are famously unsentimental about past machinery but despite having a soft spot for YYO 221 “you move it on for the next project.”

“A guy I know bought it and used it for many years. He used to bring it to us to do some work on it and I always loved it and said ‘if you ever want to sell it let me know’. That day came so I bought it back. He looked after it very well but we did a resto on it and rebuilt it.”

Its return to competition was at the 2017 Classic Adelaide, which Bates and Taylor won outright, and it’s a regular sight at the Twilight Rallysprint series held at Western Sydney Dragway.

It’s always funny to stick your head in old race cars and see what constituted state-of-the-art in times past. Don’t get me wrong, the interior of the ST205 is very neat and well-engineered, but compare it to the inside of a modern World Rally Car – or even the cabins of the Yaris AP4s that Neal’s sons Harry and Lewis run in the Australian Rally Championship – and it’s easy to see where progress has been made.

It’s a simple environment, which suits me fine; I’m told not to touch any of the switches and while the five-speed dog ’box doesn’t require the use of the clutch, please use it to give the transmission an easier time.

To my relief, a couple of solo slow laps to capture some photography are required. These allow me to become familiar with the Celica’s controls because only now, as you read this, am I admitting I’ve never driven a car with a dog ’box before.

Having heard stories of their recalcitrance, I’m not keen on making a fool of myself with Neal sitting next to me. My reservations are unfounded, with none of the expensive metallic graunching that haunted my dreams in the lead-up.

It’s a relatively easy car to drive: the clutch is quite heavy and you have to be positive with your shift movements, but the steering is light and extremely responsive and the engine is outstanding. Even without the anti-lag system (ALS) switched on there’s tremendous mid-range torque and it answers any throttle input effectively immediately.

That said, long transport sections would take a toll due to the noise and the unyielding ride, the suspension designed to soak up big hits rather than cushion the car’s occupants. And heaven help your left leg if you got caught in traffic.

Familiarisation complete, Neal jumps in the passenger seat and it’s time to stretch the Celica’s legs. I’m nervous; this is Neal’s baby that he and his team have spent hundreds of hours restoring. Asking to thrash it around Winton feels akin to suggesting a boxing match with Harry and Lewis. Our pace builds gradually to generate plenty of brake and tyre temperature, then Neal leans forwards and flicks a switch on the centre console to activate the ALS.

Instantly, the GT-Four feels as though it’s been stabbed in the heart with a shot of adrenaline, like Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction. Throttle response becomes almost pre-emptive, the car leaping forward at the slightest brush of the pedal, and a cacophony of pops and bangs erupt from the exhaust on the overrun as extra fuel is dumped into the cylinders to keep the turbo spinning constantly.

Freed from the suffocating effect of a restrictor the Celica is much quicker than it was in the day and it eggs you on, straining at the leash like an over-excited puppy. At full noise the dog ’box is brilliant, each upshift snapping through as quickly as your limbs can complete the motion, heel-toe downshifts a piece of cake thanks to the engine response and the excellent pedal placement.

The brakes are awesome, not too heavy despite the lack of power assistance and with superb feel. Likewise, the steering transmits an incredible amount of information to your hands; the rack is quick but feels entirely natural, probably because there is not a hint of slack in the system – you get out exactly what you put in.

The quality of the car is evident everywhere. The suspension setup feels very stiff but shrugs off any kerb impacts with the magical compliance that only really expensive dampers (previously TTE, now MCA in the original housings) possess.

In my hands the Celica understeers from corner entry to apex – as might be expected since Neal’s car lacks the clever active differentials of the World Rally Cars – yet as soon as throttle is applied it rotates beautifully towards the corner exit, which is surely witchcraft with a static 50:50 torque split.

It’s not necessarily at home on a circuit – in comparison to, say, a production race car or similar – but it’s still extremely capable. Neal reckons the ST205 is good for 1min30sec lap of Winton, which would match the time David Reynolds recorded at PCOTY with a Nismo GT-R!

Neal proved the Celica’s impressive tarmac credentials, however, with a dominant victory in the 1995 Targa Tasmania.

“It’s funny how that came about. We got the first [ST205] GT-Four about three weeks before Targa Tasmania in ’94; we put a roll cage in it and went to Targa, led the whole time until a rock in the radiator on the second-last stage. But all through that event everyone was going ‘it’s a factory rally car, it was this and it was that’ – it was a standard GT-Four.

“So I thought, ‘Bugger this, if they’re going to say it, I might as well bring a full factory rally car’.

“I never forget on the Prologue, which was three-point-something kilometres, we won it by 12 seconds over Jim [Richards] in the Porsche. No-one else [was] committing to the [pace] notes like we were; we went down and did a recce for two weeks, we put a huge effort in and we were reaping the rewards.”

Having endured my best efforts, Neal nestles into his more familiar seat and provides a demonstration of what the ST205 is capable of when driven properly. Despite having retired from top-line competition, the 55-year-old has lost none of his passion for driving – “I don’t do it anywhere near as much as I’d love to. I just don’t have time” – nor has he lost any of his ability.

After aggressively getting the brakes up to temperature, we attack. Neal eradicates the entry understeer by braking late and hard, mobilising the rear of the car to point the nose where it needs to go before nailing the throttle.

WhichCar Podcast episode 55: rally special

He’s busy at the wheel, the Celica is dancing and we’re using every millimetre of available road. This is not a machine that gives up its speed easily, it demands effort from the driver; Neal says the Corolla World Rally Car that replaced the 205 was only a little faster, but much easier to drive.

As I sit here and write this it’s still hard to believe I drove such a piece of rallying history; it stills feels like a dream, though when behind the wheel of such an awesome machine, the sensory overload it provides guarantees you’re never going to feel more awake.

Toyota Celica GT-Four rally car rated

5 stars out of 5

PROS Engine response; diff wizardry; gearbox; brake feel CONS No active diffs; not being able to drive it forever

Bates Toyota Celica GT-Four rally car specs

Body 2-door, 2-seat coupe Drive all-wheel Engine 1998cc inline-4, DOHC, 16v, turbo Bore/Stroke 86.0 x 86.0mm Compression 10.0:1 Power 321kW @ 6000rpm Torque 600Nm @ 4500rpm Power/Weight 268kW/tonne Transmission 5-speed manual Weight 1200kg Suspension struts, coil springs, anti-roll bar (f/r) L/W/H 4420/1770/1285mm Wheelbase 2558mm Tracks 1590/1560mm (f/r) Steering hydraulically assisted rack-and-pinion Brakes 355mm ventilated discs, 4-piston calipers (f/r) Wheels 18 x 8.0-inch (f/r) Tyres 235/40 R18 (f/r); Dunlop Direzza Price To Neal Bates? Probably priceless

Playing Possum: titanic battles with Possum Bourne

The mid-to-late-1990s was the golden era of Australian rallying. Neal’s nemesis was Kiwi Peter ‘Possum’ Bourne in his Prodrive-built Subaru Imprezas, with Ed Ordynski’s Mitsubishi Lancer Evolutions never far behind.

The record books show Possum was dominant, winning seven straight ARC titles, but rarely were the Subaru and Toyota more than a few seconds apart.

“[Possum] did beat me more than what I’d like to look at – he was far better on pace notes,” Bates says.

The worst part about [it] was that it was always incredibly close and most times went down to the last round.”

It’s a rivalry that continues today. Harry Bates secured his first ARC title in 2019 driving a Toyota, beating a Subaru driven by Molly Taylor, the daughter of Neal’s long-time co-driver Coral.