First published in the February 1974 issue of Wheels magazine, Australia’s best car mag since 1953.

In any other country his name would be whispered with awe. We look back at the life of Philip Edward Irving, the man who powered Jack Brabham in 1966.

WHEN I WAS toying with the idea of coming to live in Australia I wrote to Phil Irving and asked what the job situation was like in Melbourne. His reply was: “A worker can get work”, and he added further on in his letter: “By the way, if you’re stuck for transport when you get here I can lend you a car for a few weeks”.

Read former Wheels editor Peter Robinson’s story of how this story came to be written.

With these two sentences we have Philip Edward Irving summing himself up pretty well. Head down, get on with the job, and help others as and when you can.

And the first social function I attended in Australia was a surprise dinner party thrown for Phil’s 68th birthday. It was a surprise to him too because he’d been told that he was being carted off for a quiet little dinner but when he came into the room he found more than 80 of his friends clapping their hands. With the net thrown a little wider the figure could easily have been over the 200 mark.

Another little scene. I forgot who it was told me he had been more or less frog-marched into attending some motor or motorcycle club function at which the great attraction was a talk by Phil. This man isn’t very mechanically minded so he was looking forward to the occasion with about as much enthusiasm as an octopus has for playing the bagpipes. But as the evening went on he found himself completely captured, hanging on every word and having a thoroughly enjoyable time. There we have Irving the orator.

Then we have Irving the author, for he has produced a goodly number of books which are regarded as The Work in their various spheres: Tuning for Speed, now in its fifth edition; Motor Cycle Engineering; Automobile Engine Tuning; Two-stroke Power Units. He must have written hundreds of magazine articles, both under his own name and “Sliderule”.

And there is lrving the competing motorcyclist, competing motorist, the craftsman who can do any mechanical job that he is likely to ask another person to do. There is Irving the dry-humor specialist as well. When I was apologising for returning his Rover somewhat unwashed, he said: “Aw, that’s all right. I wash them every six months”. He paused, and then added defiantly: “Whether they need it or not!”

But above all, there is Irving the designer of engines. Had he been an Italian living in Italy, his name would be whispered with awe in every place where motorists gather, but in Australia it would seem that a prophet hath no profit in his own country.

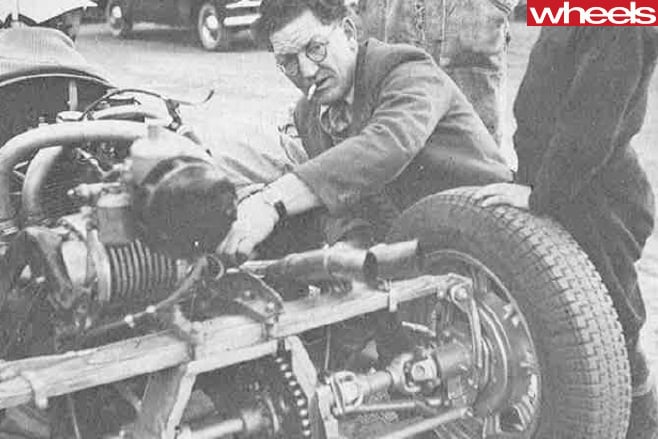

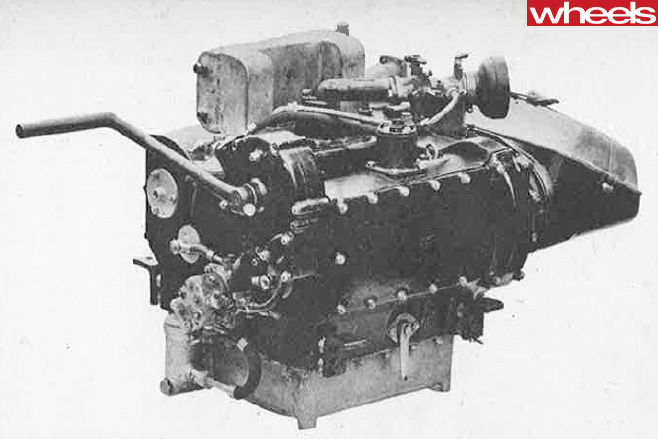

The facts of the matter are these. The Repco engine which Jack Brabham used to win the world championship in 1966 was designed by Phil Irving. The drawings were done at Aliwal Road, Clapham Junction, London, in 1964. Pencil was first put to drawing paper on March 15 of that year and the job was completed by September of the same year. And 53 weeks after the start of drawing, the first engine was running in Australia.

The whole thing was done under a veil of dark secrecy. Phil and Jack Brabham had about six meetings in the middle of the night and the engine was designed to fit the contours of a chassis design that was later discarded so it wasn’t a completely straightforward job.

Another thing that requires pointing out is the matter of the engine succeeding “because it was reliable”. That is perfectly true but that wasn’t the sole reason, because Brabham kept on getting pole grid positions and you don’t do that on reliability alone. In fact, instilling both speed and reliability into a unit is something that usually escapes most designers.

But there were write-ups about the engine and about Jack Brabham and even a film and if you searched the small print or the crowd of extras cheering in the background, you could find little trace of Irving. The engine was designed in secrecy, and a lack of publicity followed. It was only in 1967 that a CAMS award put the matter right to a certain extent. But all this happened in ’64… So let’s get it right and all chorus together: “Phil Irving is a brilliant engine designer”. And I would add that, at the age of 69, he’s no different from what he was a few decades ago.

Phil comes from a family which seems to have pretty well equipped with grey matter. His great grandfather, from Annan in Scotland (where there is a statue of him in front of a church), was a Presbyterian minister who formed a sect called the Irvingites. They have their head church in Gordon Square, London. Then his grandfather was a classics professor at Melbourne University and his father a doctor in Victoria. You just can’t keep these Scots down!

Phil went through State school, Wesley College and Melbourne Technical College before joining Crankless Engines at the age of 18, as a draftsman, which would have been in 1921 since he was born in ’03. As well as drawing, he did work in the machine shop and on stress calculations. About 1924 he was working under a man name of Sherman who, among other things, designed the valve gear for Bentley engines. A pretty good grounding and it is one of Phil’s joys that anything he draws, he can make – and indeed, has, in most cases.

Then in partnership with one Kenny Granter he set up a motorcycle dealership in Ballarat and they weren’t the only people who didn’t realise that a world-wide depression was on the way … So in 1930 when a citizen called Jack Gill arrived in Melbourne with a Vincent HRD motorcycle and empty sidecar from which his erstwhile passenger had decamped, Australia lost Irving right through until 1949. They made their way to Britain via New Zealand and Canada and Phil spent some time at a drawing board with Velocette before leaving to embark on the construction of a motorcycle to attack the world record, in conjunction with Arthur Simcock and Alan Bruce.

The machine, “Leaping Lena”, was Brough Superior based with a supercharged JAP engine. It had a solo potential of 160 mph and Bruce took the sidecar record with it at 128 mph in 1931, but the solo record eluded it mostly because of lack of time in Hungary, where the roads couldn’t be closed long enough to let them tune the engine for the conditions.

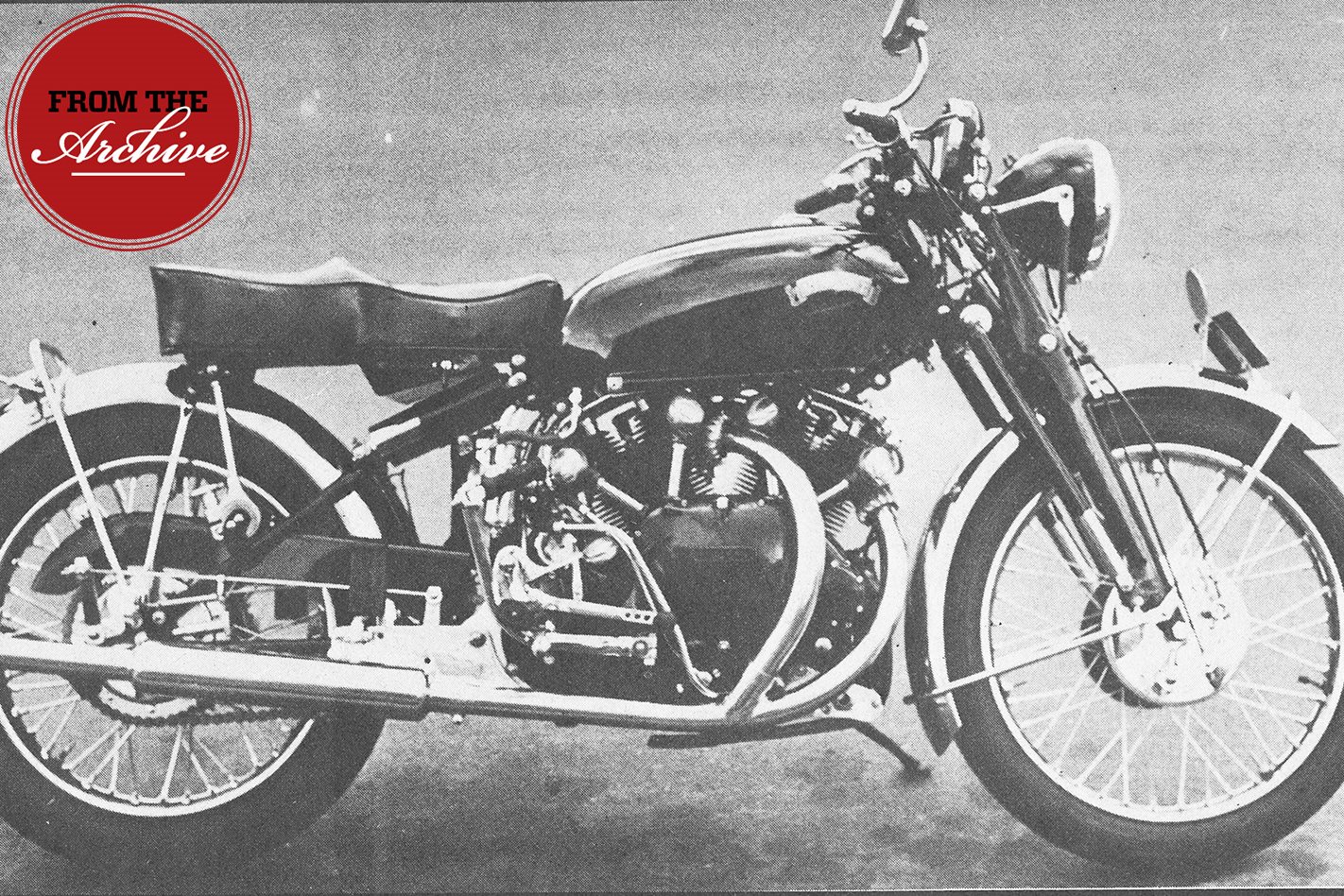

It wasn’t long before he had a job with Vincent HRD and from that union came the Series A, B and C Rapides, Black Shadows, Black Lightnings, Meteors, Comets, Grey Flashes and even at one stage, a water-cooled 250 cc two-stroke with fully enclosed engine and built-in legshields.

The basis of these splendid motorcycles was Phil Vincent’s triangulated rear suspension, at a time when the greybeards of the business had set their faces firmly against such going on. Motorcycles were intended by the Lord to have rigid rear frames, just as pedalcycles had to have big wheels until Alex Moulton came along. Another example of Irving instant design – it was decided in 1934 that Vincent would make their own engines, and motorcycles bearing them were on sale in 1935.

He has always put in fantastic hours at the drawing board and, indeed, his home is known. as Owl’s Rest, so named by his son, Denis, because of the late hours that were kept when Pa was in the throes of getting on to paper what was already in his head. “A worker can get a job.” But sometimes I look around me and observe that the non-workers are the ones with the chrome-plated offices and platinum-plated secretaries.

Then I stop to wonder if they or the workers are the happier and when I look at Phil I decide that the workers have won through by a clear margin. Would you rather look back and say: “I designed that engine” or: “I’ve tucked away half a million dollars by saying the right things to the right people?”

If you visit Owl’s Rest you will find three Rovers dotted around it and perhaps a pair of legs sticking out from under one. No need to guess who. One is a Land-Rover and the other two of the 75/90/105 series, and all are in good mechanical order. I had a puncture with the one I borrowed and when I opened the boot found two spare wheels. Knowing PEI I wasn’t surprised.

“Why,” I asked, “do you like Rovers so much?”

That almost stumped him and after wondering aloud if they had just sort of become a habit along the lines of “better the devil you know”, he decided that it was because when he bought a Rover 12 from Reg Hunt he was struck by the fact that it was very well engineered, that attention was given to details, it had a free ·wheel which he likes, a central floor change (in a 1947 model, this was), one-shot lubrication. And it is a fact that there are enough Rover spares knocking about the Owl’s Rest garage to cope with most mechanical emergencies.

I seem to have wandered off the trail circa 1935. From then on there was a bit of shuttling between Vincent, Velocette and Associated Motor Cycles (AJS and Matchless in those days) and lrving designs included the Velocette LE water-cooled flat twin, a supercharged vertical twin motorcycle of 500 cc with two crankshafts geared together, work on the AJS “Porcupine” supercharged racing machine and a uniflow engine for use in airborne lifeboats.

He did a lot of other work as well … then back in Australia to the Rolloy Piston Co where he was involved in the design of a Chamberlain flat-twin diesel tractor engine of 6-litres, which suggests a certain element of versatility!

Then a move to Repco Research, which was Lhe start of a fruitful association, and from there issued a cylinder head which would make an FJ Holden engine produce 90 bhp instead of the usual 60. A completely rebuilt engine could be bought for 450 Pounds complete, and it made the unfortunate car do 104 mph if the driver was so minded.

About 100 of these engines w3ere sold until the racing regulations were altered but they are still in great demand today, especially among the boating people, and it is said that they change hands for more than they cost originally. The good that men do lives after them…

In 1959 there began a shuttle service by ship back and forth to Britain, which went on for so long that PEI didn’t see a winter for six years. He spent his time writing books, magazine articles and, of course, designing the Brabham engine.

Phil used to share my London office not so much because he liked my company but because I had a spare desk and my secretary, Ann Emerson, could read his handwriting. I can too but some people claim to have difficulty and it may be something hereditary from his doctor father .

Good friends as we were, I had no idea be was designing a racing engine, nor did anyone else. Now and then I’d overhear a conversation in which special valves or something like that were being ordered, but for what I had no idea. Just “something for Repco” and when I look back I reckon I missed a considerable journalistic scoop.

After a time Phil worked with Repco on a consultancy basis and you may have noticed certain Holden-based F5000 engines which were “…stirred up enough to beat the Chevs”. They produce about 480 bhp.

And there is a boat called The Cheetah which does about 90 but we’re not sure if that is knots or mph. Frank Sinclair, for example, took the Australian sidecar record on a Vincent outfit and still holds it. Also with Frank he has competed in car trials and, in one memorable event , the Midnight Trial of 1951, their MG was the only finisher out of 31 starters.

He has motored over most parts of Australia, had a finger in Donald Campbell’s world record affairs at Lake Eyre, designed a dirt-track engine, evolved a banking sidecar outfit, introduced twin brakes (per wheel) on motorcycles, patented a form of adjustable rear suspension, been upset by more people than he has upset and he has shamefully undervalued his abilities and his worth. Denis on this subject: “He makes me hopping mad”.

The foregoing words probably cover about a third of what Phil has done so far, and the “so far” isn’t written without due thought. Who knows what he will design next, least of all himself, for an idea may come at any moment.

Usually, when I write articles about people, I let the victim see my golden words before they are published as a check on the accuracy of dates and so on but, in this case, Irving me ol’ cocksparrow, you’ll read it when it’s in print. Good on yer.

Combined with the relatively low physical effort required, the fast (2.6 turns) ratio means that you initially apply more lock and steer deeper than you intend, then have to wind back a bit to restore yourself to the desired line.

The radial-shod car always tracked degrees truer than the cross-piled Silver model but both (like all HQs) are inveterate understeers which demand disproportionate increases in steering lock as the cornering speed is raised or the radius reduced. This absolute only-and-always addiction to understeer unfortunately negates any semblance of throttle control and handling finesse, and ultimately leads to terminal front-end plough.

***

This was the first occasion on which we have driven the HQ Holden in really windy conditions. Contrary to expectations, in view of the prominent understeer and front weight bias, the Premiers were not unaffected by side winds and both wandered considerably, keeping us busy.

While by no means a scintillating performer by today’s mean standards, the Holden 202 six nevertheless provides entirely adequate acceleration and speed for everyday driving. And the marriage between it and the Tri-matic transmission is a particularly happy one. It’s a nice easy-driving combination thanks to well chosen ratios and (ordinarily) almost imperceptible shifts up and down the range.

Although it pulls a standard 3.36:1 final drive ratio the Silver model proved clearly quicker than the optioned edition which was handicapped to some extent by the air conditioning and power steering. This car was fitted with a 3.55:1 final drive ratio but there was little effective difference in the gearing overall because its radial tyres turned fewer times per mile (larger rolling radius) than the Silver’s cross ply tyres. So with only a nominal 0.4 mph per 1000 rpm between them in top, the gearing was near enough to identical.

To determine exactly what influence the air conditioning had on the optioned Premier’s performance we ran a full set of figures with the cooler switched off, then repeated the procedure with the air switched on. The respective acceleration times simply confirmed an obvious impression – the car was measurably slower right through the range when the air system was operating; about four seconds behind in the 0-80 mph bracket for example.

Of course in terms of everyday driving the loss of performance is relatively minor and means virtually nothing. And when ambient temperatures during the test session soared to a muggily oppressive 32 deg C we (in the optioned car) needed no further convincing about the compensating benefits of “air.

One disappointing aspect of both cars was fairly heavy fuel consumption. On one easy 337 km (211 miles) run of cruising at a very leisurely 80-88 km/h (50-55 mph) and deliberately driving for optimum economy, the optioned car (with air on) returned a welcome- but apparently exceptional – 7.52 km/l (21.2 mpg). Thereafter it averaged about 6.39 km/l (18 mpg) and sank to a low of 5.53 km/l (15.6 mpg) over a 276 km (172 miles) stint that included the performance tests.

The Silver Anniversary car was generally driven harder throughout the test, a fact brought home by its considerable thirst. It returned a low of just 5.25 km/1 (14.8 mpg) over a 295 km (184 miles) stretch which included the performance checks and gave a best, if it can be called that, of 5.68 km/1 (16.0 mpg) for 394 km (245 miles) of urban commuting and fast country cruising. Overall, the Premiers’ consumption can only be rated as poor. Whether there is any connection between the uncomplimentary fuel consumption and the advent of detoxed exhaust gases we don’t know… and the General’s not saying.

Our test was conducted before the new emissions limits (ADR 27) came into effect in January. And although the “clean” Holden engines were phased in some months earlier GMH hadn’t released details of the means by which the engines are modified and how, if at all, performance and economy are affected by the changes.

The optioned car exhibited a very annoying (presumably not typical) rattle from an ill-fitted exhaust tail pipe when accelerating hard uphill or on rough roads. But otherwise both were mechanically and bodily quiet cruising on sealed and dirt roads alike.

Wind noise was also commendably low when cruising at up to 110-130 km/h (70-80 mph) with the windows raised; indicative of good fit and sealing of the doors and glass. But the same can’t be said of the ventilation booster fan which is audibly obtrusive when operating above the slowest of its alternative speeds.

We also found the windscreen washers (on both cars) very feeble: their squirts reached only halfway up the glass so that attempts at cleaning it only worsened the spots and smears.

But overall there was relatively little to criticise on the Premiers. They’re not outstanding cars by any stretch of the imagination, but they’re not bad either – middling good in fact.

Heaven only knows what we’ll be driving, and the General will be building 25 years hence. For now, however, the Silver model seems as good a way as any of commemorating two and a half decades of Holdens.

Want to read more classic tales? Visit the Wheels Archive – simply log in here using your existing MagShop account or create a FREE account and select this article from the homepage.

Don’t have a MagShop account?

Have a MagShop account?